Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

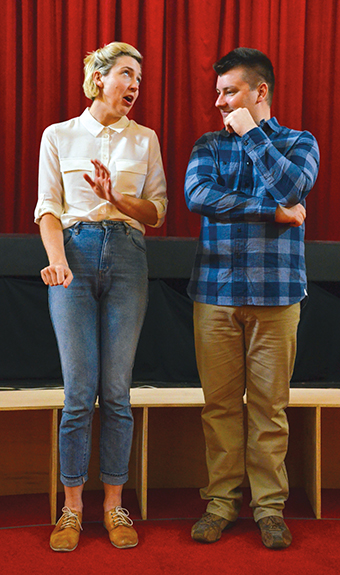

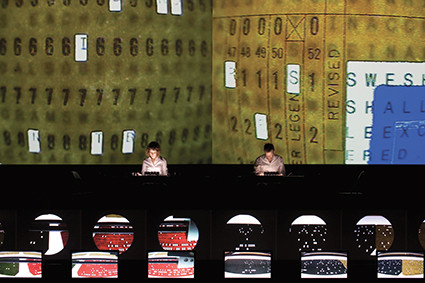

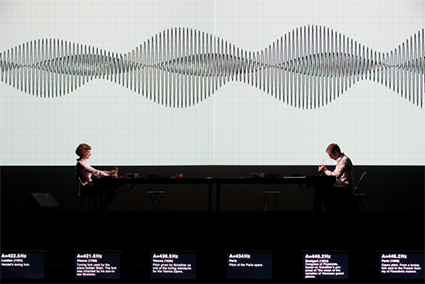

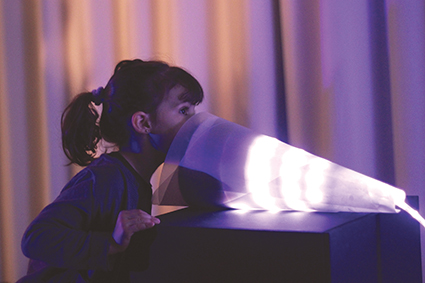

Ashton Malcolm and David Williams, Quiet Faith

photo Heath Britton

Ashton Malcolm and David Williams, Quiet Faith

A SELF-CONSCIOUS REJOINDER TO THE NOISINESS OF THE CHRISTIAN RIGHT ON THE ONE HAND AND THE SO-CALLED ‘NEW ATHEISTS’ ON THE OTHER, DAVID WILLIAMS’ QUIET FAITH WEAVES ITS MEEK PRESENCE FROM THE REAL LIFE THREADS OF THE FAITHFUL ORDINARY AND A BURGEONING CHRISTIAN ACTIVISM AS EMBLEMATISED BY THE ‘LOVE MAKES A WAY’ PROTEST MOVEMENT.

In his familiar manner, Williams recorded interviews with 20 Australian Christians of varying ages and denominations in preparation for the work and it’s their words, replicated verbatim down to every last, drawn-out “um” and “ah”, that constitute Quiet Faith’s text. The conversations Williams held with interviewees emerged from three questions: “How would you describe your journey of faith? How does faith manifest itself in your everyday life? And what do you think is, or should be, the relationship between religion and politics?”

Reviewing Williams’ program notes now, I’m put in mind of George Pell’s terse response to David Marr’s recent Quarterly Essay, The Prince: “Marr has no idea what motivates a believing Christian.” In that case, Pell was shutting the door on the possibility of a non-believer grasping such a thing; in Quiet Faith, it is Williams’ avowed intent to open it, to let a little light and air into the largely internalised beliefs of Christianity’s silent majority. It is, seemingly, a project that has been conceived with atheists and agnostics in mind, those who, like both Marr and myself, are more at home critiquing the Christian religion’s institutional failings and archly conservative social activist agenda than engaging with the views and lived experiences of everyday believers.

Williams is joined onstage by just one other performer, the significantly younger Ashton Malcolm, whose performance style provides a sometimes-jarring contrast with Williams whose approach is mimetic, soft-voiced and poker-faced, shot through with, no doubt, many of the same false starts and fillers he has detected in the responses of his interview subjects. Malcolm’s, conversely, is more embroidered, less attentive to the faltering rhythms of ordinary speech; a clear persona emerges that is warm, amused and defiantly daggy. Williams’ performance, moreso than Malcolm’s, seems calculated to drive home the dissimilarity between grassroots Christianity’s quiet emphasis on the pursuit of good works and the evangelistic social conservatism of high-profile Christian politicians like Cory Bernardi and Bob Day. Bernardi, Day and their ilk—and this, of course, is the point—seem worlds apart from the reflective, softly-spoken small-l liberals on whose words Quiet Faith is built.

“I would have said probably 10 years ago,” one of Williams’ interviewees told him, “it would have been unthinkable for a Christian in the conservative churches to not vote Liberal.” Now, such people are not only not voting Liberal in significant numbers, but are staging sit-ins at the offices of ministers on both sides of politics in protest at Australia’s continued, bipartisan policy of offshore detention of refugees.

In addition to providing a useful sketch of this shift in the relationship between religion and politics in Tony Abbott’s Australia, Quiet Faith also foregrounds the minutiae—the hymns and prayers, the church services and greetings of peace—with which the faithful daily ritualise their beliefs. Set designer Jonathan Oxlade’s rings of wooden pews, gorgeously lit by Chris Petridis’ suspended halo of lights, establish a tone halfway between intimacy and ethereality that is subtly redolent of places of worship. The performers move among, sit beside and address their dialogue directly to audience members as candles flicker here and there. At times we are called upon to stand and sing or recite—“Amazing Grace,” The Lord’s Prayer—while at other times Bob Scott’s immersive sound design, incorporating sacred organ and choir music and ringing bells, surges and then drains away. We hear, too, whispering voices: muted, indistinguishable waves of human speech that might be prayers or verses of scripture.

Finally, Malcolm and Williams embody two ministers as they debate the baptism of a stillborn baby, an act expressly forbidden by their doctrine. It is the only palpably dramatic moment of the evening and serves, inadvertently, to point up the insipidness of the preceding hour. There is no doubting the production’s elegant visual and aural design or the appeal of its careful, convincing restatement of progressive Christian values, but in its quest to achieve a meditative atmosphere Quiet Faith tends towards the simply soporific. More forgiving were the audience members who, judging by their post-performance responses, had had a Christian schooling or upbringing. Over them, at least, the work seemed to leave a pall of happy nostalgia—a mark of the successfulness of its verisimilitude, if not its ability to fully engage the uninitiated.

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 47

© Ben Brooker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

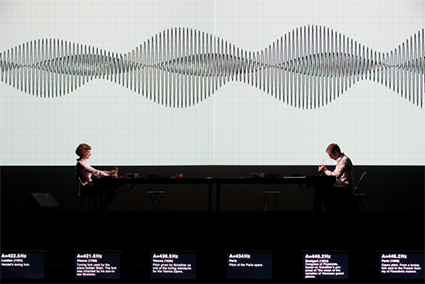

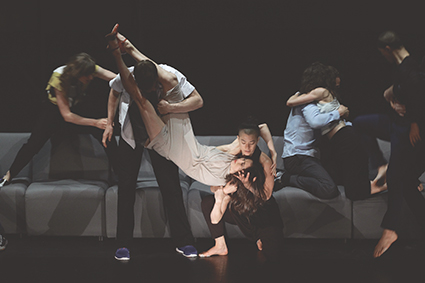

Jesse Rochow and Jianna Georgiou

photo Shane Reid

Jesse Rochow and Jianna Georgiou

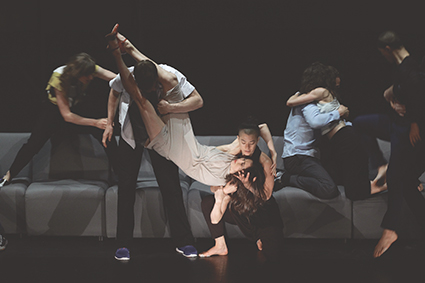

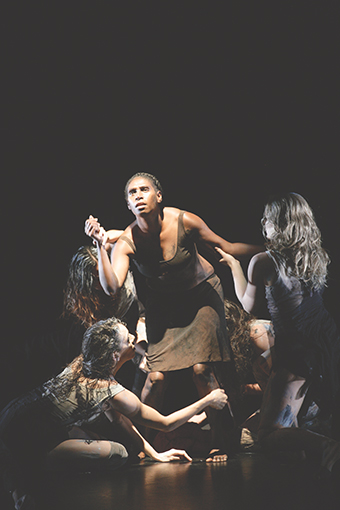

IF THE DANCE FLOOR IS A DEMOCRACY THEN RESTLESS DANCE THEATRE’S IN THE BALANCE REMINDS US THAT ITS BORDERS ARE FRAUGHT WITH, IN THE WORDS DIRECTOR MICHELLE RYAN USED TO INITIATE THIS NEW WORK WITH THE COMPANY’S YOUTH ENSEMBLE, “FLIRTATION, REJECTION, INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION.” WHILE MEMBERS OF THE ENSEMBLE TAKE TO THE FLOOR IN CHOREOGRAPHIES OF ONES AND TWOS, THE REST HOVER ON THE PERIPHERY, HERE A FURTIVE EXCHANGE OF GLANCES, THERE AN INTRODUCTION MADE AWKWARD BY LOUD MUSIC OR A LACK OF CONFIDENCE.

The anxieties only dissipate, replaced by exhibitionism or exuberance or a muscular masculinity, as the performers in turn peel off from the throng and become the focus. Each brings with them a fiercely individualised energy informed by their physical capabilities, their dynamic within the group and their relationship with the space: at ease, listless, assertive. And the space itself? A glittering state of decay, designed by Gaelle Mellis and Meg Wilson that, with its fallen, shattered mirror ball and messy assemblages of hanging ropes, tinfoil and paper lanterns, recalls the apocalyptic/hedonistic bifurcation of Prince’s 1980s heyday: “Everybody’s got a bomb/ We could all die here today/ But before I’ll let that happen/ I’ll dance my life away.”

The breadth of the stylistic diversity between the vignettes and the vim with which they are performed maintains interest, even as the production’s conceptual slightness is revealed. Chris Dyke’s lurching, sexually charged athleticism provides a fine contrast, by way of an example, with Kathryn Evans’ tender, curiously touching solo routine with an exercise ball. Intermittent group work, such as when the performers chaotically transport two sets of chairs from one side of the stage to the other, provides an additional, if still inadequate, layer of complexity. The production ultimately circles round on itself, having travelled nowhere in particular, its constituent parts diverting but disconnected. There is an elusive metaphorical quality to Ryan’s direction that remains unresolved, and only tritely treated in the program notes: “We stumble, bounce and back flip on the awkward journeys we make to become who we are.” I would have been more convinced had Ryan managed to embed something of the shape of this transformation in the work’s overall contour.

More successful are Geoff Cobham’s characteristically sinuous lighting design and The Audrey’s rootsy soundtrack, equal parts alt-country languor and T Rex-ish stomp. The Adelaide band’s 2008 single “Paradise City” makes for a fitting, if unexpected, accompaniment to Dana Nance’s introspective, yearning solo: “In this town we all bear our own load,” moans singer Taasha Coates over Tristan Goodall’s plaintive guitar, “‘cause we know what’s waiting at the end of the road.” As though stirred into action by these ill-boding words, the Ensemble subsequently unites again and In the Balance concludes as it began, with a jubilant, freewheeling group choreography.

Ryan’s darker purpose, however, remains unexpressed as the audience enthusiastically applauds each member through a final, brief solo before they bounce from the stage. If only they had begun the journey that led them there from a deeper, darker place, I might have felt like I was clapping for more than just an ending already seen, a destination arrived at rather than one never left.

Restless Dance Theatre, In the Balance, director Michelle Ryan, performers Josh Compton, Darcy Carpenter, Felicity Doolette, Chris Dyke, Kathryn Evans, Jianna Georgiou, Michael Hodyl, Lorcan Hopper, Nigel Major-Henderson, Caitie Moloney, Dana Nance, Jesse Rochow, Tara Stewart, lighting designer Geoff Cobham, designer Gaelle Mellis, Meg Wilson, music the Audreys; Odeon Theatre, Adelaide, 16–25 Oct

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 36

© Ben Brooker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Director George Mannix, PACT, 1988

JENNY NICHOLLS, FORMER PACT ACTOR, DIRECTOR AND BOARD MEMBER, HAS WORKED AS A TEACHER, THEATRE DIRECTOR AND CONSULTANT FOR THEATRE COMPANIES AND EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS AND SAT ON THE DRAMA COMMITTEE OF THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL IN THE LATE 80S. SHE’S A SENIOR LECTURER AT THE INSTITUTE OF EARLY CHILDHOOD AT MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY, SYDNEY. MORE THAN THAT, SHE GREW UP WITH PACT FROM THE AGE OF 13.

When, on the occasion of PACT’s 50th birthday, I interviewed Nicholls—who still recalls those early years with exuberance—it became clear that PACT had shaped her life and career, as it has doubtless done and still does for many others.

Originally housed on the edge of the Sydney CBD, near Darling Harbour, PACT was founded by a group led by Robert Allnutt, Jack Mannix and Patrick Milligan in response to the Federal Government’s Vincent Committee Report that “highlighted the dire state of Australia’s performing arts, film and television industries.” PACT (Producers, Authors, Composers and Talent, and later Producers, Artists, Curators, Technicians) aimed to develop a range of practitioners who would enrich Australian culture.

Central to Jenny’s experience of PACT was Jack Mannix, whose sense of community was shaped by the Depression and by the Catholic School Fellowship which encouraged young people to get involved in social activities in the 1930s. Thirty years later, when Jack teamed up with Patrick Milligan (Spike’s brother) and Bob Allnutt an ABC producer to form PACT, she says, “I think Jack’s mandate was to bring young people into the organisation and it was inherently about cultural leadership and access—and culture as a way to drive change as much as it was about an aesthetic. He felt there needed to be a way to be innovative.” There were PACT folk concerts, playreadings, a sub-group that called themselves The Leper Colony and a psychedelic theatre group, The Human Body, at a time in the late 60s when Australian playwriting was emerging.

Jack Mannix

Nicholls joined PACT in 1974 when free drama workshops were offered to teenagers. “Jack was very keen to bring in kids who didn’t have much access to culture. Culture! I use the term very broadly. I grew up on the northern beaches and I didn’t have much more access to culture than a kid from Fairfield really. I had the beach. No drama in schools. Virtually no after-school creative activity or anything like that.” Nicholls and 200 teenagers were introduced to “the great Australian do-it-yourself pantomime.” Not the English model. “No script. It was all up and down improvising, ‘OK, you go next… OK, now you swap parts.’ We were divided into groups according to where we lived and participated in three-day workshops over the school holidays. Between August and Christmas the groups alternated on weekends to rehearse and then five productions went on simultaneously throughout Sydney in late December.”

As well as going to PACT on Saturdays each week, Nicholls found herself attending Wednesday night events, mixing with older participants, many of whom were studying at university, “experimenting with poetry, movement sequences, sound, lighting, somebody walking slowly up a ladder while somebody else was reading a poem…” Later these became events titled Abstractions.

“Even though I wasn’t particularly aware of it at the time, I understand now that it was so much about aesthetics.” She quotes George Mannix (Jack Mannix’s son) from a speech at the PACT 50th Birthday celebration on 11 October, “People in the room knew something extraordinary was being created. You could have been acting or waiting your turn or doing the lighting or the music but we were all thinking, ‘Wow,’ this is amazing.’”

“PACT shouldn’t necessarily be privileged here because I think ATYP (1963) and Shopfront (1977) were also emerging. What was interesting however was that PACT moved from being a venue for folk concerts and playwrights to ‘This is great but we need more, we’ve got to do things on a bigger scale, we’ve got to get out to the suburbs and get young people in.’

“In 1976 we took the pantomime to the Chapter House at St Andrews Cathedral for a four-week season as part of the Festival of Sydney. At other times PACT would say, ‘We’ve been invited to take the pantomime to Telopea in the September holidays; who wants to do it?’ So those who volunteered would be packed off in a truck with somebody who had a driver’s licence and we’d turn up at a school or hall or whatever, put plastic black-out on the windows with gaffer tape, set up the lighting box and the reel-to-reel music and off we’d go. What an introduction to theatre at 15-16!

“I was growing up with PACT,” says Nicholls, as the organisation itself was developing its vision. She remembers being in Mannix’s productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, describing it as “environmental theatre.” It too was performed in the Chapter House, “a beautiful space—making use of the stairs and the balcony above with the audience on the floor and actors moving in and around them. Before that we did Eros and Thanatos based on the writing of [Marxist philosopher Herbert] Marcuse. We performed that downstairs at the Seymour Centre.”

Nicholls had become more than a participant: “The way the pantomime worked was that whoever did it the year before taught the next group coming in. Very privileged for me when I look back. At 14 I learn it and at 15 I’m teaching others.” There was only a scenario for the pantomime: “It was about a schoolteacher who didn’t like children and who was informed by a goodwill spirit that he had to put on a pantomime so he could learn to appreciate children. On the way he meets a whole lot of funny characters. It was interactive so at any moment you would have anything from 50-100 children on the floor of a hall and during the performance the children would be up and doing things—pretending to play a game of football or dancing around Cinderella’s coach, or holding up Jack’s beanstalk. Not only was I learning about aspects of theatre i was learning about children.”

Nicholls spent her teenage years with PACT. “We toured to Byron Bay, Canberra Theatre Festival. Then we started going out west—Dunedoo, Condobolin, Deniliquin—doing pantomimes and other performances—The Hobbit, Under Milkwood. By Year 12 I had to step back—Jack didn’t want anyone in Year 12 performing.”

So what was life like post-PACT? “After the HSC I had to decide what I was going to do. Am I going to work in theatre or is this place my family? And it had been my family. When I started at PACT I don’t think I knew much about what university was really. But according to Jack, all of us kids were going off to university—it was the Whitlam years—and we did. Well, not everybody but it was expected.” Clearly PACT itself provided quite an education: “You can just imagine hearing all these poets being talked about and quoted in performances—like TS Eliot. At 15 I knew the entire script of Midsummer Night’s Dream. We all did. I played Helena one year and Puck another year.” Nicholls chose the University of New England in Armidale: “In 1979 there were few universities offering a drama course with a strong practical focus.”

Drama at university was quite different from PACT: “I loved it. It completely challenged me because suddenly I’m doing warm-ups in drama classes. We never had warm-ups at PACT. At PACT it’d be, ‘If you want to get to know each other, go into the office and have a coffee’ and ‘Now we’re rehearsing.’ At uni it was great, full-year drama courses, sometimes two a year from Ancient Greek classics right up to “read two Australian plays a week, discuss them and write our own!”

In her final year Nicholls re-connected with PACT: “George rang me to say that he couldn’t go down to Berrigan in the South-West Riverina with the PACT production this year, would I like to. By now I’d finished my degree and had my teaching diploma. So I went and did something similar where I created a show with young people over three weeks. This led to a 12-month teaching appointment as a drama consultant in the Riverina.” The following year Nicholls was accepted into the directors’ course at NIDA, even if short on some of the technical audition demands. “I tell this story to my students. I didn’t need to be an expert in everything. I needed to have a vision, which is in fact what Jack had and everybody came along with his vision. I don’t put myself in Jack’s category but I think I’m visionary and innovative in my work.

“So I went to NIDA for a year, was an Associate Director at STC for 12 months, did some work for Jigsaw Theatre Company, travelled overseas for 12 months and came back to be met at the airport by current PACT staff and friends who asked me to work as artistic co-ordinator. And so I did. It was half time, not even that. PACT received a tiny amount from the Australia Council. I supplemented that by doing casual teaching and I helped organise the transition from Sussex Street to Erskineville, when we got kicked out.”

IN 1989 Nicholls staged the first full-scale production in the new PACT home in Erskineville, Playing for Time, an Arthur Miller film script—based on the life of Fania Fénelon, a Jewish prisoner of war in Auschwitz who formed an orchestra in the camp. Beginning outside the theatre, Nicholls separated the audience from their partners and moved cast and audience around like inmates. This ‘environmental’ tradition continues to this day at PACT with the constant, inventive reconfiguring of the space and its outdoors.

By 1990, says Nicholls, “I really couldn’t survive any more on a part time salary. I completed a Masters Degree in Theatre Studies at UNSW and was offered the opportunity with Sydney College of Advanced Education, teaching drama courses—and I was getting paid well.” The SCAE was amalgamated with Macquarie University and Nicholls moved into the area of Early Education. She says her teaching over many years is still grounded within the artistic philosophies of her years in PACT. In 2008 she was awarded a citation for outstanding contributions to Student Learning by the Australian Learning and Teaching Council for her innovative work in student engagement in drama and online technology.

Nicholls was on the PACT Board when Jack Mannix died in 1989: “He had a heart attack and was on life support for a while. I can remember everyone was running in and out of his hospital room playing music and singing pantomime songs, combing his hair…He hated having messy hair.”

I ask Nicholls to describe Mannix. She responds thoughtfully, “I think he was a visionary. He had extraordinary patience and a great relationship with young people. We thought he was the opposite of a father or grandfather figure; he was just an amazing adult. I don’t think anybody thought that he was particularly old. He just was. He smoked a pipe. The way that he created shows with young people was extraordinary—the discipline he demanded, the self-confidence he developed in kids from all backgrounds; and the ideas he introduced us to—art, literature, music. It was about getting young people to rise and rise to the best of their ability. I think that for a lot of people who’ve left PACT and gone on to make their own creative work, that’s [something they took with them.]

“And it was also about making beauty. George and I were talking about this last night and he said, ‘It’s hard to talk about beauty now. We talk about truth when we go to the theatre.’

“Jack was caring and gentle and absolutely of the belief that culture should be accessible and people should be able to have the opportunity to participate in the making. He said it better: ‘instrumentation of creativity.’ He was also very inclusive; nobody was excluded; there were no auditions, no try-outs. It was just that gentle way he had of saying, ‘You try reading Helena or you do Bottom.’ He just intuitively knew.”

Jenny Nicholls completed her many years with PACT by becoming Chair of the PACT Board FROM 1988 to 1994. She reminds me at the end of our interview, that her story is only one of hundreds from young people who were introduced to theatre (and so much more) at PACT.

In RealTime 125 (Feb-March 2015) we’ll look at the years since and the artistic directors and teachers who have maintained the PACT vision in their distinctive ways.

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 37-38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

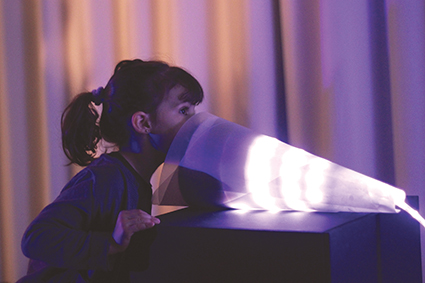

Margaret Cameron, Opera for a Small Mammal, Chamber Made Opera

photo Daisy Noyes

Margaret Cameron, Opera for a Small Mammal, Chamber Made Opera

UNFORGETTABLE, WHETHER WHEN WE FIRST SAW HER IN 1986 AT PERFORMANCE SPACE IN ULRIKE MEINHOF SINGS, DIRECTED BY NICO LATHOURIS, OR ON THE MAINSTAGE IN JENNY KEMP’S PRODUCTIONS OF CALL OF THE WILD (1989) AND JOANNA MURRAY-SMITH’S NIGHTFALL AT THE SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY IN 2000 OR, ABOVE ALL, IN HER OWN THINGS CALYPSO WANTED TO SAY (1990) AND KNOWLEDGE AND MELANCHOLY: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL FICTION IN 2004, AGAIN AT PERFORMANCE SPACE.

We wish we’d seen her later performances and more of her acclaimed directing, which we first glimpsed in Aphid’s 2003 puppet-play trilogy A Quarreling Pair and last witnessed in Chamber Made Opera’s Minotaur The Island, for which she also provided the text for David Young’s composition, in the Aurora Music Festival in 2012 in Sydney’s west.

Acting, directing, writing or just being, Margaret was a dynamic presence, at once authoritative and intimate. Her idiosyncratic weighting of words, the lateral lilt of her sentences and that distinctive tone, all at one with her art, will long be recalled and treasured.

Keith & Virginia

In the archive

The RealTime archive includes responses to Margaret’s work and an article by her, “Art & care: where life and death connect”, which she wrote for us in 2013 in RT117.

Margaret on acting

Virginia Baxter’s hithero un-archived 2000 interview, “The other side of Nightfall” (RT 37, p29), with Margaret and fellow actor Ian Scott, also appears in the November edition of Profiler. It’s a wonderfully incisive account of the nature and complexity of acting in general and in response to Joanna Murray-Smith’s play Nightfall, Jenny Kemp’s direction and Elizabeth Drake’s score.

In Nightfall, Margaret and Ian play a middle-class couple, Emily and Edward whose daughter Cora (Victoria Longley) disappeared when she was 16, assumed abducted. But seven years later a go-between, Kate, arrives to negotiate the return of Cora—who is revealed to have left home of her own accord. In most respects Nightfall is a conventional play, well crafted, suspenseful and morally complex, but Cameron, Scott and Kemp made it something more in the perturbing rhythms of the playing. Cameron’s approach brought the same kind of subtle attentiveness to a naturalistic play that she would to an experimental work with powerful results.

Here are two excerpts that tell you something about Margaret and her art.

“The approach to the play for me was a matter of the whole body physically listening. The listening body is like an animal: you can get caught, suspended; you’re hunting the sense and the emotional sense. Jenny Kemp is a very good director for me in that she loves to see that. If you get stranded halfway, held in space, Jenny’s in a state of delight because it’s dangerous. She credits the invisible world. She understands it as present.”

“[Emily’s] emotional/physical world is adrenalin, huge expectation and capping and locking a terrible fear that things might not be all right. It’s a paradox she starts with, an expectation equaled by massive fear. And they’re balancing each other. That’s her place. And she keeps working towards the belief that Cora will come in that door at any moment. She’s sincerely trying to help Kate. And the pressure will shift me around emotionally so that if on a particular evening there might be a point reached in the graph, which is a little bit unexpected or the intensity is less than last night, what happens is that it goes somewhere underneath. It’ll curve around and sort of push you in another sequence. So you’re playing the essentials every night but where they occur is moveable and very volatile. It’s quite frightening to perform.”

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch & Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

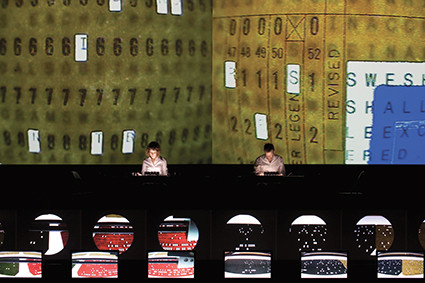

TimePlaceSpace

photo courtesy Performance Space

TimePlaceSpace

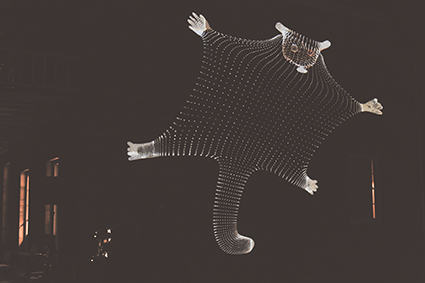

FROM 26 SEPTEMBER TO 12 OCTOBER, THE TIME_PLACE_SPACE LABORATORY TRAVELLED FROM SYDNEY TO KANDOS, GANGUDDY/DUNN’S SWAMP, CANBERRA, NARRANDERA AND BACK TO SYDNEY. EVERYONE INVOLVED, AND INDEED EVERYONE WHO CAME INTO CONTACT WITH THIS TRAVELING EXPERIMENTAL ART LABORATORY AROUND REGIONAL NSW WAS UNANIMOUS IN ADVOCATING THE WONDERFUL VALUE OF THE PROJECT.

Despite numerous debriefings with participating artists in the weeks since, however, there’s a difficulty in articulating what the experience means.

By virtue of the democratic structure and Open Space philosophy that governed our time together, the lab possessed a genuine responsiveness that allowed everything to be adaptable according to the desires of the 20 diverse artists present, as well as the facilitators and provocateurs. This included everything from how and where we lived together, to how we should work together, and on what exactly we should work. Working time (there was an incredibly vocational attitude taken by all involved) was split between collaborative making between artists within the specificity of the locale and situation, and artists running workshops.

Workshops were not about teaching per se, but about sharing and responding, about seeing how different practices and outlooks speak to your own, and how yours speak back. The true value of the trip can perhaps be located within this conviviality, in the self-reflexivity the time provoked in us as individuals and as a temporary community. Away from normality and everyday lives (including the internet, which was sadly a significant factor), we were away from a knowingness of our methodologies. In this space we were able to shine light on the unknown unknowns of our own and others’ practices.

These unknown unknowns began to become transparent in an exercise early in the laboratory with provocateur Karen Therese. Karen’s exercise was itself a throwback to the very first Time_Place_Space that she participated in as an artist in 2002. We shared with each other our individual artistic manifestos and then commenced quick-fire performed manifestations of these there in the bush with each other. How was the work we were making out here different and how was it the same? What does this work reveal and not reveal about us as artists, and about the world today? How do we decide what to do and what not to do?

What we were doing was symbolically epitomized a few nights later when artist Megan Cope undertook a “toponymic intervention,” projecting the Indigenous name for the land on a rockface of the Cudgegong River, Ganguddy. It was inspiring, not just in terms of reclaiming Australia’s geographical places, but also in terms of what this trip was about. We were not traveling to colonise, but to decolonise. We were decolonising our own practices. We were peeling back layers of methodology and understanding established over time.

Time_Place_Space: Nomad was about having a look at what it is we really do, with all known frameworks stripped away. We were decolonising time, place, space and the act of thinking for each other, and were doing so through our work. We were also doing this for the members of the public we encountered on the trip, through sharing and collaboration on what we were up to. A Xanadu Swamp processional-art-rave at Ganguddy/Dunn’s Swamp was followed by a number of events and exchanges in and around the Narrandera showgrounds the following week.

It feels fair to say that this process created a degree of doubt in all who participated—the sort of doubt that takes place before the self-examination that leads to transformation. A safe space to raise such doubts and such self-examination is certainly a good thing, even if it is a struggle to articulate what that good thing actually is. No wonder then that it has been difficult to articulate the outcomes, for the outcomes are incredibly personal and shifting revelations of personal traits and dispositions.

Performer and video, sound and installation artist Zoe Scoglio wrote of “a shifting of my axis, a broadening of my points of reference, an exciting newness that I’m eager to see unfold in my practice…re-affirming the importance of aligning one’s way of living with one’s artistic ideology.” Artist Mish Grigor (performer and member of post) found a similar fascination in “the way that the lines between art and life became increasingly blurry” across the laboratory, noting “by the end we were a nebulous cult society, where every meal had a conceptual framework.” These meals included Fluxus “Identical Lunches” by TPS provocateur Song-Ming Ang (a Singaporean live artist/ musician) and a dinner led by cross-disciplinary artist Tessa Zettel made entirely of food bartered for, foraged and found. Mish too wrote of an enthusiasm for the more concrete outcomes of the lab, without knowing what or when they might be: “[TPS] required serious consideration of every moment’s possibilities. It will be interesting to see what repercussions it has for the structures, communities and artworks that we operate within over the next couple of years.”

Weeds advocate, forager and artist Diego Bonetto offered a spirited provocation towards realising the outcomes of the lab: “Fuck manifestos! Fuck channelled visions, however well-meaning and educated they might be. Fuck defined, preconceived and goal-oriented efforts. Humanity needs to be much more fluid than that, adapting and fast moving, unpredictable and crafty, ever changing, finding communal visions and driven by constant questioning.”

It was this constant questioning that drove our decolonising. It drove our composting and sambal, our drones and rock sundials, our tyvek bubbleheads and twilight choreographies, our evacuation procedures and boguing, our hammock time and bird watching, our mobius spiralling and silent walks, our wombat poo necklaces and shadow play, our nature dying and heavy drinking. It was our constant questioning that drove more questions to arise—about climate change and how we live, as much as any about artistic practice.

A communal vision was found in Time_Place_Space: Nomad that exemplified the connections and culture that can be made in a relatively short amount of time when privileging process, which doesn’t happen this way in metropolitan contexts. We realized this decolonised vision together, as artists, researchers, zealots and playful children. Special mention must be made of co-curators Bec Dean and Angharad Wynne-Jones for making it happen. In the end, we all drank the kool aid together and returned to our respective versions of the ‘real world.’ Changed, somehow. Nascent projects and processes latent for action. The answers to most questions are still TBA, possibly forever. Not least for me: What do you really mean when you use the word ‘amazing’? And, how exactly do you find an ending?

http://time-place-space.tumblr.com

Time_Place_Space: Nomad is an Australia Council initiative to invigorate interdisciplinary and experimental arts practice in Australia, with an emphasis on collaborative performance-making, site-specificity and artistic resilience. The first six laboratories were managed by Performance Space, 2002-09.

Australia Council for the Arts, Time_Place_Space: Nomad, co-production Performance Space, Sydney, Arts House, Melbourne, participating artists Connie Anthes, Diego Bonetto, Megan Cope, Mish Grigor, Sophea Lerner, Jamie Lewis, Jessica Miley, Fee Plumley, Greg Pritchard, Bhenji Ra, Zoe Scoglio, Ria Soemardjo, Latai Taumoepeau, Nathan Thompson, Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal, Malcolm Whittaker, Tessa Zettel, Julia Carr, Joshua Jackson, Helen Yung; provocateurs Song-Ming Ang, Lee-Ann Buckskin, Karen Therese, Lee Wilson; facilitators Bec Dean, Angharad Wynne-Jones, Richard Manner, Michael Petchkovsky, Sophie Kitson, Kate Brown, 26 Sept-12 Oct

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 39

© Malcolm Whittaker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Imagining O

photo Marina Levitskava

Imagining O

THE MEETING POINT FOR REHEARSALS FOR RICHARD SCHECHNER’S PERFORMANCE WORK, IMAGINING O, BASED ON PAULINE RÉAGE’S CHARACTER O FROM HER CONTROVERSIAL 1954 NOVEL, STORY OF O (WHICH SCHECHNER DESCRIBES AS A LOVE POEM) AND HAMLET’S OPHELIA—WITH A FEW ADDITIONS FROM SOME OF SHAKESPEARE’S OTHER FEMALE CHARACTERS—WAS THE DIRECTOR’S OFFICE AT NEW YORK UNIVERSITY.

Adorned with ancient masks, photos and thousands of books from his many years as Founder and Professor of Performance Studies at Tisch School of the Arts, the office is the nerve centre of The Drama Review and the home of the brain behind the birth of the Wooster Group/Performance Group in the 1960s and is crammed with an eager cast from around the globe. Fourteen women and one man are all ready to dive into an intense six weeks (six days a week) working on Imagining O. All set for an investigation of sexuality, abjection and power and one of those ensemble experiences where people respect each other’s work and where you are given freedom to exercise your creative imagination. How often does that happen in life?

Richard greets me with a warm hug. We had last seen each other the previous year in Brisbane where my company, Tashmadada, had invited him to conduct a four-day Rasabox master class at the World Theatre Festival. Schechner devised the Rasabox training in the 1980s-90s, based on the Natyasastra, an ancient Indian text on stagecraft. It’s a training methodology to give performers concrete physical tools to access, control and communicate eight key emotions for performance. It was an essential part of the rehearsal process: when working on scenes, Richard would prompt us with a specific ‘rasa’ to explain an emotion he was searching for—or a phrase of dialogue. Some chunks of text had a different ‘rasa’ for each sentence—or even within one sentence.

I jumped right in—straight onto the floor and working physically. And straight into the transgressive subject matter of O—a character whose sexual fantasies involve unusual “alterations” of the body. No room for puritans in O’s cupboard. Not that this particular ensemble needed much prompting, everyone displayed great ease with their bodies. Richard, at the epicentre, created an environment in which trust, bravery and a feeling of ‘I can do anything’ existed. inhibitions dissolved quickly.

Each day for the next six weeks started with yoga—a specific form that Schechner has been practicing daily since the 1970s—and he is testament to its effectiveness. At age 80 the mind is sharp and the body still flexible—he often sits in lotus position. It’s a yoga series given to him by his Indian teacher and is invigorating without being too strenuous. As well as physical poses, the yoga includes vocal work and a very particular breathing series, which required tissues at hand.

After the daily trip to the Alexander Kasser Theater in Montclair, where the rehearsals took place (necessary for this site-specific promenade work) and the performances were to be staged and hosted by Peak Performance Festival, we were fuelled by caffeine and a passion for the new found material. Lunch was sporadic and dinner at 10 pm after coming back to Manhattan—who cared as the days were full of stimulation.

One of the daily theatre exercises included crossing from one side of a defined space to the other but infused with specific instructions. The exercise was a template for exploring all sorts of ideas—such as Schechner’s interest in slow motion as a tool to train the body, focus the mind and to create intense relationships between members of the ensemble. One variation saw us crossing the space as slowly as we possibly could (with Richard side coaching us to go even slower) and, on meeting each other, slowly swapping clothes. After the clothes swap we could continue our extremely slow walk. If not all clothes were swapped we had to be totally still until the exercise was over. It took at least an hour to cross the small space and it engaged every muscle in my Suzuki trained body, tested my focus and challenged my tenacity—all of which, until then, I had felt were strong.

United by the training regime and collective film shoots around Manhattan—including filming some of us performing movement sequences as we plunged into the waters off Coney Island, and on an early morning train in our ‘dressed to kill’ clothes—the ensemble forces grew stronger and the groundwork was laid for us to devise our own material. At one stage, in the final performance, the audience needs to perform tasks in a carnival scene before being allowed to progress to the next stage of the show. I ended up on my back on a specially made see-saw exhorting members of the public to feed me real flowers—they weren’t shy and I often had a number of them at once stuffing as many into my mouth as they possibly could (that image ended up accompanying the glowing reviewof the production in the New York Times, 12 September).

We were charged with devising solo pieces, our ‘dispersals,’ to explore whatever interested us in relation to the themes of Story of O. I was more than ready to abandon myself to whatever boundaries were to be transgressed. Thematically, I was particularly interested in the physical and emotional decomposition of both the O and Ophelia and their ultimate demises. My piece involved an atmospherically lit bathroom (thanks to lighting and set designer Chris Muller), hanging flowers, dripping liquid, a soundscape, a naked body (slightly faulty) and instructions for the audience to draw on my skin. I won’t say more as I am developing this into a durational piece.

Six weeks living and breathing with a power ensemble of gorgeous and talented women, of immersion in the art of Richard Schechner, one of the fathers of avant garde theatre (he is a grandfather now) with his lively, curious, razor sharp mind and endless energy, has breathed such life into my own being that I will treasure the experience for a long, long time to come. The sold-out shows for Imagining O have provided great external recognition but nothing compared to the internal emotions and sensations still resonating in my body.

Peak Performances: Imagining O, rehearsals commenced 4 Aug; season, Alexander Kasser Theater, Montclair State University, New Jersey, 10-14 Sept

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 40

© Deborah Lieser-Moore; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Yalin Ozucelik, Richard Roxburgh in Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Cyrano de Bergerac

photo © Brett Boardman 2014

Yalin Ozucelik, Richard Roxburgh in Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Cyrano de Bergerac

IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, THREE PRODUCTIONS IN SYDNEY IN RECENT WEEKS—TWO OF THEM OF NEW AUSTRALIAN PLAYS BY WOMEN ABOUT WOMEN AND ONE A CLASSIC BY A MALE ABOUT A MALE—SHARED A REVEALING FOCUS ON PERFORMANCE. CYRANO DE BERGERAC, A FEMALE STAND-UP COMEDIAN AND A FAMOUS NOVELIST, PATRICIA HIGHSMITH, ALL BECOME EMOTIONALLY UNSTUCK WHILE ATTEMPTING TO SUSTAIN PERSONAE THAT MASK VULNERABILITIES.

STC, Cyrano de Bergerac

A man of enormous pride and charisma, a popular poet and accomplished swordsman, Cyrano de Bergerac nonetheless dooms himself to misery in the belief that he is unloveably ugly. Richard Roxburgh as Cyrano delivers the requisite crowd-pleasing bravado with panache and deals his enemies just the right degree of cruelty, verbal and physical. But, deftly and incisively, Roxburgh reveals the cracks early on—a palpable fragility, sentences that come unstuck when Cyrano’s not on show—preparing us for a darker, less melodramatic demise than usually anticipated: a tragedy imbued with a touch of the manic depressive.

Eryn Jean Norvill’s Roxane appearing at first a delicate flower is soon shown to be intelligent, forthright and physically robust—an ideal partner for Cyrano, if only… Chris Ryan’s Christian is a charming innocent, played with a kind of engaging Ocker ease. Josh McConville’s Guiche is convincingly both scary and comic. The mobile 17th century stage within the Sydney Theatre’s large open space presents numerous opportunities for lively staging and amplifies the sense of performance that is Cyrano’s outer world; the inner one he cannot enact. Sharp-eyed, witty direction and economic adaptation (Andrew Upton), fine period design (Alice Babbage), an immersive sound world (Paul Charlier), characterful casting and a superb Roxburgh all made for a seriously memorable Cyrano de Bergerac.

Cast: Fiona Press, Madeleine Benson, Susan Prior, Nat Randall, Genevieve Guiffre, Is this thing on?, Belvoir Downstairs

photo Brett Boardman

Cast: Fiona Press, Madeleine Benson, Susan Prior, Nat Randall, Genevieve Guiffre, Is this thing on?, Belvoir Downstairs

Belvoir, Is This Thing On?

The very title of Zoe Coombs Marr’s Is this Thing On?, a riotous depiction of the life of a female stand-up comedian, Brianna—played by five actors across her life—is telling. If the mike is not on, what next? Or what if you stand before it and you can’t speak—that’s the very first and very young Brianna (Madelaine Benson) we see. The stage is then seized by an MC (Susan Prior) who treats us as comedy club innocents, spitting out bad jokes, letting us know she also works the bar, gossiping about fellow comedians.

The script loops back to a younger Brianna, Genevieve Giuffre, finding her way in stand-up, studying veterinary science, and then another, Nat Randall, more confident, dropping out of university, coming out and unleashing a string of crudely funny, discomfiting fisting jokes. An older Brianna (Fiona Press), back in the business after a breakdown, is relaxed, cynical, the jokes grosser, still working the bar, prone to anger, violence even against a male comedian friend who left her show stranded.

It’s Susan Prior’s Brianna who cracks—she’s unstoppably frantic, barely leaving space for laughs in case there’s silence, bullying her audience, relentlessly on the move, no longer able to veil the anxieties breaking through an already unstable comic persona. It’s an unnerving performance, loud and rarely funny in a conventional sense.

Zoe Coombs Marr writes in her program note, “Since we first met, comedy has been like a charismatic but occasionally abusive lover that I haven’t quite been able to turn away from.” A member of post and a solo performer, Coombs Marr started out in stand-up when she was 15. Is This Thing On? is a grimly articulate account of engaging with your craft, its limits, dangers and a little of the joy of connecting with your audience, and it achieves this by doing it—making us witness how stand-up does and does not work and the pressures that build behind confident facades. There’s little detail in the show about life beyond stand-up, like family or love—save the charismatic abuser mentioned above, comedy itself—but fragile self-love and the courage to perform to make an audience love you, these are revealingly and depressingly on display.

Sarah Peirse and Eamon Farren in Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Switzerland

photo © Brett Boardman

Sarah Peirse and Eamon Farren in Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Switzerland

STC, Switzerland

Actors and stand-up comedians are public performers, writers are deemed private if increasingly having to front their audiences at writers’ weeks and in the media to ensure book sales. The great American crime writer Patricia Highsmith, self-exiled to France and then Switzerland after having felt underappreciated at home and finding herself much admired in Europe, did her fair share of interviews, but not always agreeably. She was even less amicable socially as she grew older and irascible in private. For all her many friends, numerous female lovers and several sustained if fragile relationships, Highsmith seems to have been a loner of a kind with her racial prejudices and fetishes, including a love of snails, fascinated as she was with their sex lives, keeping them in a pocket or leaving them about her house. The oddities of her Texan upbringing, the eternal tensions between herself and her mother, her New York youth and early career (as a well-paid comic book writer during world War II), a promiscuous life in the lesbian community and the failure to break through into the pages of The New Yorker, all combined to create a distinctive personality, bristling with contradictions (Jewish good friends, flirtations with men) which yielded an acute alertness to moral ambiguity with insights into double lives, jealousy and criminal desire—principally realised in the form of her male characters.

Joanna Murray-Smith conjures up Highsmith’s final days in a Swiss mountain ‘bunker,’ alone, bitter and alcoholic, dealing with a young publisher’s representative determined to coax her into writing another Ripley novel. The previous envoy suffered a breakdown, believing that Highsmith had threatened him in his bed with a knife. The new arrival appears to be destined for the same, or worse (he wakes with a nick on his neck). For all his naivety—he can’t handle Highsmith’s caustic wit and relentless abuse—he is oddly determined, eventually finding his way to break through, largely through discovering a shared blokey interest in guns and then urging the writer to improvise the opening scenario for a new Ripley novel, which she does, but imposing on him the responsibility of deciding how the murder is committed—a decision she will regret since it will play some part in the young man’s transformation—a very Highsmith one.

Switzerland is an entertaining and suspenseful two-hander. Sarah Pierse is an ideal casting choice as Patricia, not only having something of the look of Highsmith about her, but with her slight drawl, her staggered walk and a pained stoop she conveys both old age and something predatory. It’s a shock when, alone, she dances falteringly to a beloved show tune (one of the real Highsmith’s pleasures). Eamon Farren’s young man, Edward, has the indeterminant demeanour of a Ripley, his persona mutating across the play’s three acts—innocent, then manipulatively probing and then… Like Ripley, he’s a performer. In Act One we believe him, his American clichés failing to cut though Patricia’s well-established obstinacies and prejudices. In Act Two, he’s a touch smarter, doubt creeps in.

The three-act structure is not perfect. Act Two, instead of following up on the cut the young man finds on his neck in the morning and entwining it suspensefully with what follows, moves rather expositionally on to everything we need to know about Highsmith, with a consequent slackening of pace and suspense if interesting in itself (her obsessions, paranoias, her objections to America etc) and providing some fuel for the young man’s machinations (guns, vulnerabilities). Act Three begins strikingly, some of the audience laughing with surprise at something as simple and so telling, plot-wise, as a costume change.

If you buy the conceit that Highsmith finds herself trapped in a plot very much like the ones she wrote, then you’ll be satisfied with Switzerland, but you wouldn’t want to think about it too much. A long-term Highsmith fan, I greatly enjoyed Switzerland, despite Act Two’s slackening and Act Three’s less than inventive ending; the performances are engrossing and there are moments when Murray Smith captures Highsmith’s creepily crystalline way of describing the world and her capacity to throw us into moral confusion.

Unfortunately, the inner-dramaturg on automatic, I thought too much about Switzerland and had to ask some difficult questions. Is Patricia Highsmith, who has told us so much about criminal minds and readers’ perverse desires (for Ripley to ‘get away with it,’ or “the complete corruption of the reader,” as Patricia puts it) and who was cruel but never herself a criminal, due the punishment Murray Smith deals her? What kind of wish fulfilment is going on here? Secondly, why run with the obvious Highsmith formula—why not replace Edward with a young woman who might re-ignite a spark of sexual desire in the dying Patricia and make more pivotal and more ambiguous the “You excite me!” passage in Act Three.

Highsmith kept her writing about women discrete from her crime writing in the non-crime novels and in Carol, her ‘lesbian’ novel, but here’s an opportunity to bring the two worlds together that co-habited the writer’s psyche. When Patricia, who obstinately lives in the past, asks Edward to speak to her of New York diners and the young women who lunch there, he informs her that there are very few diners anymore—and that young women have changed “Don’t do that!,” she snaps, upset. Patricia lives in the past—in my Switzerland she would be confronted by the present as it was in 1995, the year Highsmith died. Different play, different writer, but questions worth asking and which tell us something about the conservative nature of Murray Smith’s otherwise admirable venture.

Few crime novels are perfect, onstage crime plays even fewer, but fans, as with most genre writing, are forgiving. Also Switzerland is pleasantly not unlike seeing a movie in a cinema: it’s wisely interval-less, the soundtrack like a moody film score (initially a distant, piano and lush strings, later dramatic big guitar and continental mandolin) and it has a low ceilinged ‘widescreen’ ultra-real set—apparently a replication of Highsmith’s final home, replete with the loved portrait of her younger self, thumbs up, in red. Switzerland is a cosy, intelligent entertainment, blessed with an excellent performance partnership in Peirse and Farren directed by Sarah Goodes.

Sydney Theatre Company, Cyrano de Bergerac, writer Edmond Rostand, adaptation, director Andrew Upton, original translation Marion Potts, Sydney Theatre, 11 Nov-20 Dec; Belvoir, Is This Thing On, writer, director Zoe-Coombs Marr, co-director Kit Brookman, design Ralph Myers, Belvoir Downstairs, 2 Oct-2 Nov; Sydney Theatre Company, Switzerland, writer Joanna Murray-Smith, designer Michael Scott Mitchell, composer Steve Francis, Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House, 3 Nov-20 Dec

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 41-42

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

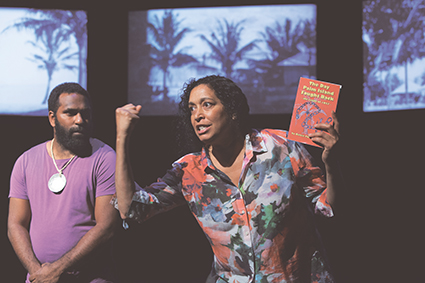

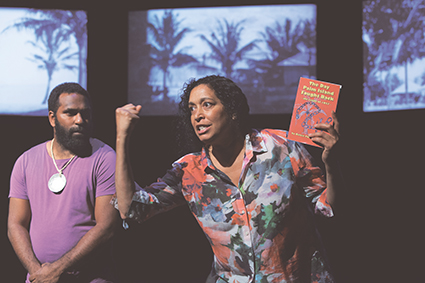

Nadeena Dixon, Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor, The Fox & The Freedom Fighters, Performance Space

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nadeena Dixon, Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor, The Fox & The Freedom Fighters, Performance Space

I’D LIKE ALL PERFORMANCES TO BEGIN WITH SOMETHING LIKE THE INDIGENOUS SMOKING CEREMONY. THE EFFECT IS CALMING AND PREPARES US TO ENTER ANOTHER REALM. SUCH WAS THE FEELING AS WE WERE WELCOMED INTO THE SPACE FOR THE FOX AND THE FREEDOM FIGHTERS BY UNCLE MAX (MAX DULUMUNMUN HARRISON), A YUIN MAN.

The ‘fox’ refers to Aboriginal activist and social pioneer Charles (Chicka) Dixon (1928-2010). Three years in development, this work has been conceived and co-created by Chicka’s daughter Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor and granddaughter Nadeena Dixon with a team of collaborators including co-writer and dramaturg Alan Valentine and director Liza-Mare Syron.

Three components of the design (Nadeena Dixon, Clare Britton) combine to reflect the work’s structure: a large central screen for film sequences (and doubling for an ASIO document); a small platform with a microphone for sung segments; and a spare living room set-up where mother and daughter casually exchange memories of the man who radically affected their lives. The spare design is enveloping and incorporates a set of striking woven sculptures by Nadeena Dixon, which grace the walls and cast enigmatic shadows. As they converse, Rhonda separates raffia threads while Nadeena weaves the circular forms of a new piece.

The performative style aims to be laidback but at times the demands of conventional theatrical dialogue appear to hinder the rapport we sense between mother and daughter. The powerful film segments (Amanda King, Fabio Cavadini) are more effective with the women appearing to be unscripted and more spontaneous. Generous archival footage provides insight into the important work of Chicka Dixon-—his involvement in historical events such as the 1967 Referendum, the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, the Aboriginal Arts Board and a visit to China in 1972. All this is woven together with the quietly intense statements on the impact of this activism on family life delivered individually to camera by Rhonda and Nadeena.

Most engaging in this work is the opportunity it offers us to meet two very interesting women and to share with them the unravelling of an intimate and difficult truth. “Don’t you for a minute think that there isn’t a cost to every single moment of this fight for freedom,” says Rhonda. And we don’t. As they reveal with passion and humour the highs and lows of life with an admired patriarch—his many absences, the alcoholism, which he eventually overcame but which clearly affected their early lives and manifest in stress and abuse in subsequent relationships—we experience the recovery of intimacy with their father and grandfather along with their own unfolding activism, all woven into the complex issues of everyday life.

The Fox & The Freedom Fighters, concept, creation, performers Rhonda Dixon Grovenor, Nadeena Dixon; Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sydney, 13-22 Nov

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 43

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Adriane Daff in Falling Through Clouds

photo Jarrad Seng

Adriane Daff in Falling Through Clouds

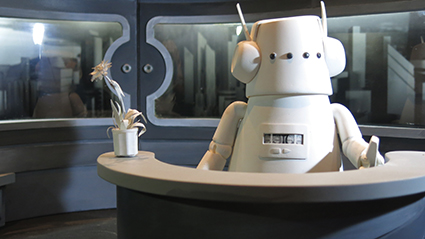

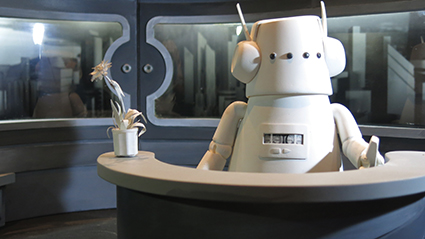

SPECTACULAR PUPPETRY, INNOVATIVE VIDEO AND HAUNTING MUSIC IN THE LAST GREAT HUNT’S FALLING THROUGH CLOUDS CONVEY A TALE OF IMPOSSIBLE DREAMS. ONE HUNDRED YEARS AFTER BIRDS HAVE DISAPPEARED, DR MARY MILLER HAS FOUND A WAY TO BRING THEM BACK AND HAS BEEN GIVEN A YEAR TO HAVE THEM FLYING. FROM HER OPENING DREAM OF FLIGHT, THE DEVOTED DOCTOR’S DELIGHT GRADUALLY TURNS TO STRESS AND OBSESSION.

In a dream-infused narrative, a research facility is established, eggs are fertilised, incubated and hatched. Mary monitors the growth and development of Henry and Jenny as they grow into their long necks, bills and legs. Teaching them to fly is frustrating, but the joys of interacting with Henry’s mischief and Jenny’s affection seem worth the worry, until deadline day. In a nightmarish sequence, Jenny is taken to the top of a cliff and sent over the edge—she panics, twitches her wings and plummets to her death. Mary’s instructions to end the failed project include specific directions to destroy all biological specimens herself, leading to a memorable chase scene with Henry and a beautiful sequence leading to the titular notion of Falling Through Clouds.

Adriane Daff (Dr Mary Miller) is a joy to watch. Her face conveys emotion intensely, amplified by combined techniques of theatre and hand-held camera working to produce a sense of real-time documentary. She rises to the acting challenges presented by film and stage, simultaneously, particularly in her dream sequences and also at the magical moment featuring a bird’s eye view of her from the interior of an eggshell breaking open.

As with previous works by this team, truly wonderful puppetry emerges, even when using balls of shredded paper. From the first tiny hatchling wing shivers to the clack clack of the feet of growing birds and their inquisitive and mischievous head and neck movements, close behavioural observation and dedicated puppetry technique bring birds to life with as much excitement as if they really were the first avian life in a century.

The set constantly changes, a particular highlight being the creation of the research facility using sheets of paper. It features a micro set of the island on the dark expanse of the stage, with hot air balloons flying above, changing our perspective, and fans that create the winds also clearing the ‘set’ once done. This sequence epitomises the careful simplicity sustained through the performance.

Thoughtful technical work sees simple projection used with low-tech ‘screens’ to create dreams of flying birds and a beautiful night sky. Use of simultaneous projection with the hand-held camera is particularly effective in Jenny’s failed flight attempt and wonderful when tracking Henry’s curious roaming around the closing facility. Classic puppetry provides elegant presentations of flight and weightlessness, contrasting with the chillingly creepy use of a moulded mask of Daff’s sleeping face. Henry’s escape is a beautiful collection of visual techniques, smoothly transitioning from live video streaming to a theatrical depiction of overhead lights, a simple exterior shot and then a sweet animation clearly telling his tale without any text distracting from the scene’s magical whimsy.

Integral to the performance, the sparse use of text is made possible by Ash Gibson Greig’s sound design and song selection, featuring poignantly weighted lyrical timing.

A visually beautiful work, accompanied by beguiling sound design and a mesmerisingly sweet narrative, Falling Through Clouds celebrates the considerable talents and achievements of its creative partnership.

Falling Through Clouds features in the 2015 Sydney Festival’s About an Hour program; Seymour Centre 16-18 Jan

PICA & The Last Great Hunt, Falling Through Clouds, initiating artist, co-creator, performer Tim Watts, co-creator, performer Adriane Daff, co-creator, performer Arielle Gray, co-creator, performer Chris Isaacs, composition, sound design Ash Gibson Greig, PICA, Perth Cultural Centre 22 Sept–11 Oct

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 45

© Nerida Dickinson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Uncle Murray Harrison

photo Liz Crothers

Uncle Murray Harrison

WITH THE SLASHING OF SENIOR CITIZEN ENTITLEMENTS AS PART OF THE BUDGET RELEASED EARLIER THIS YEAR AND SEVERE CHANGES TO ACCESSING UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE, REBEL ELDERS, A COMMUNITY-BASED ART PROJECT FOCUSING ON THE PAIRING OF ELDERLY PERFORMERS WITH YOUNG MUSICIANS COULD HAVE BEEN A DARK AND SOMBRE AFFAIR.

Instead, musician and community facilitator Rose Turtle Ertler conceived a work where the audience experienced a mischievous interruption to the looming social welfare cuts. Inspired by the Australian Human Rights Commission’s “Facts or Fiction: Stereotypes of Older Australians” (2013), Ertler gives us a refreshing and heart-warming celebration of diverse intergenerational storytelling through interview recordings, music and performance.

It’s fitting too, that this project takes place in Ballarat, known for its historical uprisings. In the theatre space of the Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka, Rebel Elders takes a more personal road when addressing civil disobedience. Seated on a line of hard backed chairs, the elderly performers face the audience and listen intently to the introductory sound fragments of their newly remembered stories, then one by one move forward to elaborate physically. It’s a silent interaction—with each other, alone and occasionally engaging with props, adding dimension to the recordings we hear.

Ertler’s process is an inclusive one; eight Ballarat elders were interviewed about rebellion in their lives. These stories became the departure points for young local musicians to produce radically different works to accompany them. We hear hip hop, ballad and guitar rock soundtracks alongside micro stories of rodeo and radio, a soldier going AWOL, secrets being divulged, Violet Crumble thievery, youthful runaways and a boxer not wanting to be boxed. Always with gems of elderly wisdom attached: “There’s always an upstager wherever you go, there’s always a knocker.” The emotional significance of these connections between old and new holds weight. Rebel Elders lends us an empathetic ear, stitching up the tear in our society and reaffirming the similarities between generations.

The random pieces of the sound design mimic the way we retrieve events in our lives and how these change subtly with time and location. They’re also episodic, encoding both mind and body: the bold act of a 14-year-old girl to wear fashion not fit for the 50s and the dramatic parental response — to “cut the skirt up, break the heels of my shoes”—is the catalyst for a runaway. The surprising twist to this guitar riffing tale was that in the simple act of not giving her name to police the narrator was placed in a convent for bad girls for over five years. These stories speak to us about the double-sided nature of defiance, dislodging the usual stereotypes of the elderly while also highlighting the need to find a place in the world.

The music was as varied as the stories. An elderly man decked out in an old military jacket and flying goggles with which to navigate the stage, spins circles in his wheelchair and plays air guitar with unflinching bravado. His tale slows to describe siphoning petrol while the beatbox soundtrack uses mouth and guttural utterance to amplify our sense of the experience.

CJ Ellis

photo Liz Crothers

CJ Ellis

With direction and choreography by Michelle Heaven, there is an impressive renovation of memory. Contrasting and complementing the recorded dialogue between the ages, Heaven picks up these rebel yarns and knits us a curious fabric of embodiment: a meshwork of repetitive gestures, thumping hearts and chance happenings. She relocates our perception with a simple use of movement evocative of the honesty in the words we hear. The choreography generates a place where the storytellers re-enact their very own characters, as if co-starring with their younger selves.

There’s a constant shift between literal representation and movement cycles that are more ephemeral in nature. Lighting by Bluebottle delivered simplicity, with occasional moments of visual trickery—larger than life shadows thrown on the backstage wall, the flickering of mismatched lamps highlighting the range of characters emerging. The performers do well to create cohesion in their storytelling, the errors in their movement real and endearing, serving to express how the elderly are misrepresented in mainstream media. Then we drift into a ballroom sequence evoking love and it’s heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

Rebel Elders reveals the importance of voice, where mining the mind is a personal act of rebellion within itself, a quiet protest. When it’s filtered through a combined 635 years of life there is resonance in the air, signifying that small choices can create huge change. The performance itself was the most interesting act of rebellion and the incredible people within it defied all labelling. They were real.

Rebel Elders, concept, sound design Rose Turtle Ertler, director, choreographer Michelle Heaven, lighting Bluebottle, Elders: CJ Ellis, Helen Gower, Uncle Murray Harrison, Victor Linane, Sue Morse, Kath Morton, Tom Rush, Trevor Williams; Young Musicians: Beatboxbo, Joint Beatz, Jake Dunmill, Rhiannon Howard, Reece Kelly, Jessica Moller, Kate Moran, Tabitha Rickard, Tobi Sam-Morris, Jennifer Rose Smith; City of Ballarat and Victorian Seniors Festival; M.A.D.E. (Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka), Ballarat, 31 Oct, 1 Nov

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 44

© Klare Larson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

cast of The Dad Show

photo Megan Spencer

cast of The Dad Show

BRON BATTEN GETS AROUND. TESTING OUT NEW PERFORMANCE (MELBOURNE’S LAST TUESDAY SOCIETY), EMBODYING THE POWER OF HYPNOSIS (USE YOUR ILLUSION, RT123, P37), AND HERE SHE IS IN REGIONAL VICTORIA, WELCOMING US INTO THE BEAUTIFUL BLUESTONE OF ST MARY’S IN KYNETON—HALF WAY BETWEEN THE CULTURAL EPICENTRES OF MELBOURNE AND CASTLEMAINE—SEATING US WITH LOCAL FAMILIES KEEN TO SEE THEIR FATHERS’ FIGHT OR FLIGHT RESPONSES LIVE ON STAGE. AS SPEAKERS BLARE ROLLING STONES (TO INFURIATE PUNTERS AFTER THE BAND’S CANCELLATION AT NEARBY HANGING ROCK), WE’RE READY NOW FOR THE DAD SHOW.

Bron (this show calls for first names) introduces herself and her dad James via slide show and poorly executed jokes (hers and his). For a previous show Sweet Child of Mine (2011) she tells us having spent a number of years on stage dressed as a humpback whale, she went around with a video camera to her parents’ home to ask them, “What do you think I do for a living?” Soon realising they had no idea, she decided to help by bringing them on stage. Here, she continues the theme, asking various father-and-son/daughter combos to perform their roles, variety style.

After a ‘real live dad’ hands out hot, weak Milo (the taste of camping), Sarah and Robert read their relationship through email, exploring what memory looks like (plasticine), how hard it is to say you don’t believe in God (when your father does) and how excruciating it is sitting in the front row watching The Vagina Monologues (when your daughter’s starring in it). The dynamic between seasoned performer and novice is negotiated carefully (and this continues through all the acts): as Sarah projects, Robert reads shyly from his notes. It is his reticence that draws my attention. So too with Bob Snelling, who takes his son Wes on a sketchy fishing expedition—ritual for the modern male—a love/hate affair. As fish-out-of-water Wes turns the radio up loud and refuses to touch worms; Bob gently coaxes him into using the rod and pats his shoulder uncertainly when tears come; salt of the earth meets high camp.

Hal and Michael (guitarists and singer-songwriters, 20 years apart) play each other’s songs for the first time together. One hipster-shaggy, the other baby-boomer-cool, they share a stance and straight-legged jeans, and as their shadows merge into one behind them, their acoustics throw off awkwardness and find comfort in convergence. The son’s face becomes joy. Henry Vyhnal’s face becomes grief as he plays his father’s violin and revisits Antonin Dvorak’s “Humoresque,” a piece of music he played at his father’s funeral. While father and son may share the language of music and moody phrasing, this act explores what’s left when one of you is gone. Hannah and Bernie share a storytelling language too but their words don’t quite relate. As Hannah reads from her journal about slowly starving to death, her father sings “Your looks are laughable, un-photographable” and dances in the moonlight; a tug-of-war between who most wants to be centre-stage.

While a loose framework of variety-hour connects the acts, The Dad Show doesn’t quite hang together. Bron’s patter before and after each performance doesn’t add to the overall cohesion, but she does make you feel like you’re hanging out with that try-hard relative who makes you cringe and want to escape the kiddies’ table. A New-Faces-Frank-Sinatra duet with her dad, where he sings “Something Stupid” and she brings in contemporary dance, is a good place to end. But what’s missing, given the show’s family focus and the building we’re sitting in, is a sense of Kyneton. I wish Bron’s dad had done a snapshot history, a male-jokey narrative of the place and its people and how the dads of the show fit into it.

The most powerful dad moment of the night comes via video. Literally lost in translation, Christian is interviewing his father Barnabus and asks him to tell a joke. While father and son arrived from Hungary in 1980, Barnabus is now in a residential care facility with Parkinson’s disease. On camera and up in bed drinking with a straw that occasionally sneaks up his nose (not an intended joke but funny nonetheless), Barnabus tries with difficulty to pull words and concepts together — running priest, minister, nurse—sometimes in English, mostly Hungarian, while the humour (tears stream down my face) comes from our imagining what the joke might be and exquisite if unintended timing. The punchline is irrelevant. When Christian asks his dad, Do you love me?” he answers, “I love you and all the other kids too.” Off the side of the stage, Christian (tears stream down his face too) explains that before he made the video, he hadn’t seen his father smiling or laughing for seven years. It took a dad joke to do it.

The Dad Show was developed and presented as part of Punctum’s Seedpod Amplified extended residency program, encouraging performers to make new work in regional settings.

The Dad Show, Punctum Inc and The Last Tuesday Society, performer, curator Bron Batten, featuring Christian and Barnabus Bagin, James Batten, Hannah and Bernie Monagle, Hal and Michael Langley, Peter and Sarah Lockwood, Wes and Bob Snelling, Antonin and Henry Vynhal, St Mary’s Hall, Kyneton, Victoria, 7-8 November.

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 46

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucas Stibbard and Tim Dashwood

photo Ben Eyles

Lucas Stibbard and Tim Dashwood

JUST AS TRAVEL CAN BE ENLIGHTENING AND TRANSFORMATIVE, SO TOO CAN THEATRE. BOTH HAVE POTENTIAL TO CHANGE THE WAY WE SEE THE WORLD, AND OURSELVES IN IT. PACKED, A CO-PRODUCTION STAGED IN ALBURY-WODONGA BETWEEN HOTHOUSE THEATRE, BRISBANE’S METRO ARTS AND THEATRE GROUP THE ESCAPISTS, PUTS TRAVEL AND TRAVELLERS UNDER THE MICROSCOPE IN A DYNAMIC PIECE OF THEATRE.

It was clear from the outset that Packed was going to do things differently. The B52’s classic travel anthem “Roam” played as the audience took their seats, while Timothy Dashwood—beer in hand—left the stage and wandered around the theatre striking up easy conversations with patrons about their travels.

Packed tells the story of two characters, simply referred to as He and She, who represent the extremes of travel personalities. He (Dashwood) in his beer logo singlet, is the likable, loutish Aussie bloke who has swapped his 9-5 responsibilities for a life of travel, ticking off his travel experiences with an equal love of drinking and selfies. She (Neridah Waters) in her sensible walking boots, cargo pants and scarf, is the hard-working anthropologist, writing about and observing the world at one remove. They collide, literally and hilariously, in an unnamed foreign land, where despite the vast gulf of their differences, they fall in love.

Lucas Stibbard (Book) cleverly plays both He’s travel guidebook and She’s anthropology manuscript. By personifying these two books, as vastly different as their owners, Stibbard’s character adds a whole other riotous dimension to the plot and themes.

He has his beer; She has her notebook. He unashamedly wants to suck the marrow out of his experiences, “I’m a tourist, we touch everything.” She is above the consumerist tourist mentality. Eventually though, She realises she is merely “hiding in a study of the world that doesn’t have me in it.”

The script (co-written by Matthew Ryan and Stibbard) is fast and tight; a hilarious swirl of anthropological theory, observation and travel stories. Even random German words are explained in formal lecture style. The cast give standout performances throughout the, at times, manic scenes—lots of climbing, running and leaping. A sense of movement is also conveyed with small, careful effects like She’s wiggling her ponytail on the back of a motorbike.

The deceptively simple set, consisting of a section of white carpet and three carpeted cubes, was used to maximum effect, creating everything from towers to planes and motorbikes. The large screen on stage added a more complex layer to the story constantly transforming the stage to keep pace with the busy script. Animations (by Pete Foley) were a clever addition to the text-heavy story, transporting the audience to a whimsical faraway land of flying ‘sky yaks.’

There were funny asides about Pluto no longer being a planet and cats having supernatural powers. The audience hit giant balloons around the theatre and the typed pages of the anthropology manuscript floated down on the stage. Like the very best travel adventures, Packed was full of laughter, wisdom and quirky, unexpected delights.

Hothouse Productions, Metro Arts & The Escapists: Packed, co-creators: Keith Clark, Jonathon Oxlade, Matthew Ryan, Lucas Stibbard, writers Matthew Ryan, Lucas Stibbard, design Jonathon Oxlade, lighting Keith Clark, composer Chris Perren, AV design Pete Foley, The Butter Factory Theatre, Wodonga, Oct 23-Nov 1

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 47

© Kate Rotherham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

TWO RECENT PERTH PRODUCTIONS HIGHLIGHT CONTRASTING WAYS IN WHICH DANCE CAN CROSS AND PROBLEMATISE THE BORDERS OF COMPREHENSION. AIMEE SMITH AND BEN TAAFE’S FORAY INTO BORDERLINE OUTLINES THE STARK CONTOURS OF COMMUNICATION THROUGH MOVEMENT AND SOUND, WHILE DANIELLE MICICH (DIRECTOR) AND SUZI MILLER’S (WRITER/CO-DEVISOR) CONCEPTION OF OVEREXPOSED, WITH DRAMATURGY BY KATE CHAMPION, SHATTERS THE CERTAINTY OF UNDERSTANDING. BOTH BRING INTO QUESTION THE LIMITS OF PERFORMANCE: NEITHER GIVES DEFINITIVE ANSWERS.

Borderline, Aimee Smith

photo Emma Fishwich

Borderline, Aimee Smith

Borderline

Aimee Smith is a wizard at constructing penetrating images whose barbed irony agitates and/or needles into matters of environmental concern. Borderline continues to explore this crafting although, on this occasion, the movement pictures and their reverberations are locked in a pervasive sense of doom. Even the dancers’ sometimes astounding wrestling with the demons of this age of herd obeisance, excessive waste and purported individualism bows to a bleak evaluation of human destiny. If the work is an anguished protest against the insanity of our behaviour in and for the planet, as I am sure it is, the cry is harsh and unremitting, seemingly devoid of any hope of rebirth. The gold glitter and hysteria-whipped bodies of the final image, indeed, act like incisive punctuation marking the withering of human imagination.

In three sections, the work begins with a weighty social organism lurching “Into the Fold.” Random impulses for freedom and/or escape conveyed through individual dancer’s unleashed limbs and torsos are crushed as the herd mentality re-ingests the errant body back within its turgid vortex. Choreographically impressive as it is, the tenacious grip of this community is born of containment not of support.

Hints of wasted social relationships become literal in “No Man’s Land” as Laura Boynes tentatively advances across an empty space only to be submitted to a barrage of fabricated rubbish and dumped bodies hurtling around her. The debris amasses, leaving her poised like the Statue of Liberty or the feminine symbol of justice garlanded in a glut of grime and senselessness. It’s a haunting image of silenced freedom and equity. The anti-visionary triptych concludes with “Trans Form,” flipping the herd anxiety of the opening into a cult of individuals blindly chasing the glowing capitalist shrine of fulfilment. Even given the tongue-in-cheek voice-over of Ben Taafe’s soundtrack, I couldn’t dismiss the association of a trail of ever-smiling and vaporous ‘selfies’ supplanting their human originators. Pointedly, perhaps, the dancers only showed their backs as they advanced and recircled towards the edge of the illuminated madness. Was Smith and Taafe’s message to turn around and face the terms of our own self-destruction?

Overexposed, Danielle Micich

photo Ashley de Prazer

Overexposed, Danielle Micich

Overexposed

Surveillance in theatre enters into a double-bind or conundrum as the audiences of Overexposed watch, record and judge what transpires before them, for the most part, from the anonymity of darkness. However, if the topic of the performance is framed and bound to policing human behaviour, its secrecies, disorientations and lies are curiously turned back onto its audiences, who might find their normal privileged role eroded. Danielle Micich’s Overexposed does not take this approach directly but the nett effect of its structure unmoors spectators from familiar logic and lands them in an alien territory of evaporated rights.

The promotional material indicates that the protagonist, Marisa, is inexplicably detained on her arrival into the home airport after a trip. What happens after this Kafkaesque premise occurs in two rooms. Obviously, surveillance is involved, which is playfully reinforced by a security check on spectators’ arrival for the performance. For inexplicable reasons, some members are stamped red in this process, while others are given official clearance in spite of the tell-tale bleep signals at the metal detector archway. It turns out that the stamping is a lottery determining to which viewing room the spectator will be allocated, neither of which tells the complete story, if in fact a complete story is ever to be told.