Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

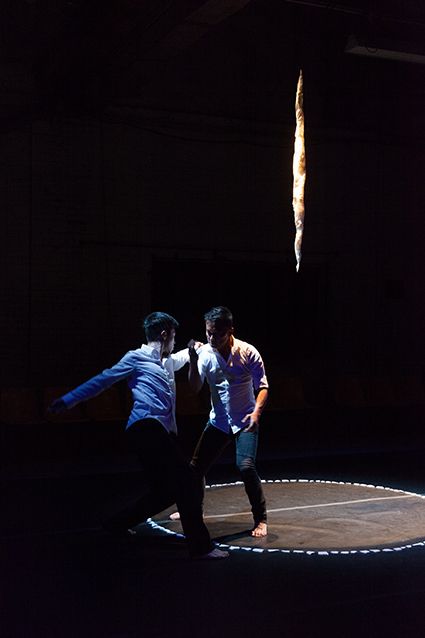

Time Alone

photo Holly Jade

Time Alone

The Totally Huge New Music Festival in Perth was brought to a stunning conclusion with Time Alone, a program of percussion and clarinet music infused with electronics. Visiting artist Claire Edwardes brought a vibrant enthusiasm to the stage, guiding the audience through a program that she clearly loved. She was joined by Perth based percussionist Louise Devenish and clarinetist Ashley Smith, both in fine form.

Chris Tonkin’s IN provided a vivid exploration of the sonic possibilities of a bass drum excited by different materials and processed through electronics. Edwardes coaxed ethereal drones, squeals and shrieks from the drum using a variety of mallets, fingers, bouncy balls and at one point a scrubbing brush. Tonkin’s electronics interacted with and warped the sound, not overpowering it but complementing Edwardes’ gestures. Ghostly fragments of speech speckled the work’s texture. IN is never boring, constantly turning corners into new and unfamiliar sonic territory.

Ashley Smith takes the foreground to perform Magnus Lindberg’s decibel-pushing Ablauf, a work that prompts the elderly woman in front of me to immediately put in earplugs. Smith’s performance is very present and gripping as he interprets the multiphonics, screams and shouts with gusto. Edwardes and Devenish, each at a bass drum on opposite sides of the stage, interrupt with gestures that gradually break away from one another. Put simply, the overarching shape is a decrescendo, and though the piece comes to a soft end, tension and atmosphere are sustained throughout.

Damien Ricketson’s Time Alone is a beautiful solo for vibraphone and electronics. Edwardes performs lonely, meandering melody while subtly manipulating the vibraphone’s motor to affect reverberation. The electronics are hushed at first but begin to bring out and play with the resonance of the vibraphone. What begins as an introverted hum develops later into foreign morse-code-like rhythms, drawing us down into what feels like an underwater texture. For all its simplicity this piece had a powerful effect, shimmering and glistening with a certain timelessness.

Time Alone

photo Holly Jade

Time Alone

“There’s a reason why people use sticks on a marimba,” says Edwardes as she and Devenish prepare for Michael Smetanin’s Finger Funk. They play with fingers only (though their thumbs are reinforced by erasers to protect against pain). The result is a ghostly and insect-like timbre. I wouldn’t expect such a specific, soft textural effect to be sustained for an entire piece, but Edwardes and Devenish manage to coax vastly different sounds from different dynamic effects and utilise the entire range of the instrument with sweeping glissandi.

Smith took the reins once more to perform Nico Muhly’s It Goes Without Saying for clarinet and electronic backing. The prerecorded electronic part explores an aggregated clarinet sound, playing with a texture that feels like it breathes heavily. Smith’s part weaves in and out of focus with fluid lines that contrast against Muhly’s agitated backing texture. His playing is elegant and refined but perhaps more valuable than the piece warrants.

The program is brought to a close by a stunning rendition of Ligeti’s Continuum, a direct transcription for vibraphone and marimba from the original harpsichord part. The earthy harmonic sound of the marimba works well with the sparkly vibraphone wash to create a spiraling cloud of sound. The piece is exciting and visually striking, a perfect end to this years Totally Huge festival.

Zubin Kanga

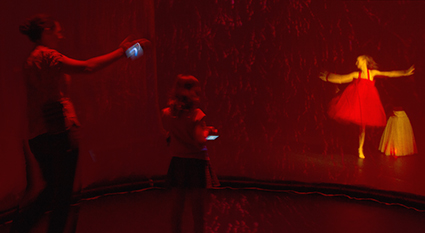

photo Holly Jade

Zubin Kanga

In a recital of fresh new piano works, London-based Australian pianist Zubin Kanga explored the concept of expanding the scope of the piano through electroacoustic manipulation and video projection. Over the course of his career Kanga has firmly established himself as a fierce supporter of contemporary music, commissioning over 50 new works for the piano. Indeed, the oldest work on this program was composed in 2009. He even hijacked his own interview with ABC presenter Stephen Adams midway through the concert in order to protest the recent reallocation of Australia Council funds to George Brandis’ arts ministry, a statement that drew enthusiastic cheers and applause.

The concert opens with Piano Hero by Stefan Prins, in which Kanga operates a MIDI keyboard that in turn triggers video samples of a pianist, shown via projection. The virtual pianist manipulates the inside of a grand piano with a variety of tools and broken keys. The video skips around, playing with speed and reversed time, messing with our perception of pace through the work. Though the video is absorbing to watch, the true strength of the piece is not in what we hear or see necessarily, but in the fact that we understand how it has been made and that we can see this process unfolding before us. Kanga’s program note suggests that the piece is a comment on the trend of the virtual replacing the real and indeed the chain of command from MIDI keyboard to projection suggested a kind of redundancy.

Julian Day’s labyrinthine Dark Twin pitted Kanga against a prerecorded version of himself playing rhythmically relentless clusters. At first the live performance is indistinguishable from the electronic, but as a disparity is slowly revealed the sound begins to sparkle hauntingly and a range of ethereal colours are introduced. The depth of the sound seems to continuously expand as the tone colour of the electronics obscures the rhythmic clarity and takes the piece to quite a dark place. The electronics perfectly complement the live sound, clouding but not obscuring Kanga’s energetic performance.

Live electronics were further explored in Benjamin Carey’s _derivations, a program developed as part of his PhD at UTS. The goal of _derivations is to follow the improvisations of a solo performer and learn from the sound—at first mimicking, but growing eventually into an intelligent duetting partner. The piece unfolds with beautiful harmonic tensions, with Carey’s electronics expanding the depth and density of the sound world quite tastefully. It was a little hard to get a sense of the ‘intelligence’ of the _derivations program, as it seemed to merely repeat Kanga’s phrases back and add reverberation. It would have been interesting to hear the piece go on for much longer, or to hear _derivations respond to a much more minimal improvisation, so as to highlight the interaction between parts. One also wonders about the ownership of this piece—so much of the artistry of the sound and success of the piece came from Kanga’s mindful improvisation.

Zubin Kanga

photo Holly Jade

Zubin Kanga

Two works of Michel van der Aa are brought together to create Transit: his tense Black and White film Passage and his piano work Just Before. On the screen we see an elderly man struggle with loneliness and repetition. He is trapped in a claustrophobic apartment and struggles with menial tasks such as opening a door or boiling a kettle. The rhythm of the film is mirrored in live piano and electroacoustic parts. This performance made use of very sudden moments and maintained a quite an agitated atmosphere for its duration.

In Daniel Blinkhorn’s FrostbYte: Chalk Outline, footage and field recordings of the Arctic Archipelago of Svalbard are met with a tinkling piano sound and icy electronic effects. The work captured a sense of open space with resonant gestures interacting with periods of silence. Fairly late in the piece a rhythmic impetus was established, with dubstepian thumps and clicks as the footage took an industrial turn. The video footage was partially obfuscated by special effects and filters that felt a little unnecessary. Nonetheless this was quite a successful work, capturing what felt like a very personal impression of the glacial Arctic landscape.

Cat Hope’s new work, The Fourth Estate, focused on interference, using radios and EBows as “sonic barriers” to Kanga’s fluid piano part. My impression of the piece was perhaps the opposite of what Hope intended—in fact the work inside the piano and the hushed radio noise blended very well with Kanga’s playing and created quite pleasant listening. Indeed, it was these extra colours provided by the interference that gave the work its energy. The program note states that this work “explores the damaging influence that the media can have on all aspects of society”. I obviously cannot speak on Hope’s behalf, but to me this feels like a contrived interpretation of the concept of interference, perhaps designed to give the audience something to hold onto as they listen but probably not an informative part of the compositional process.

Kanga concluded his program with a visceral performance of a new arrangement of Steve Reich’s Six Pianos (1973) by Vincent Corver for only one piano and four pre-recorded tracks. Kanga clearly enjoys himself as he performs with clarity and precision, bringing out the lines of most interest. Along with many other audience members I found myself having to stop myself from tapping my foot and nodding my head in time to the incredibly rhythmic music. However I do wonder what was gained by performing such a piece with only one piano instead of six, except of course practicality—it is certainly less visually stimulating. Perhaps it allowed us an insight into the interaction of one specific part against the wash of sound, to guide us through the piece—and Kanga’s part certainly did have all the most interesting gestures. It was certainly a fitting end to the technology-infused program.

Zubin Kanga

photo Holly Jade

Zubin Kanga

Nestled in plastic lawn chairs on the ground floor of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the eighth night of the Totally Huge New Music Festival featured world-renowned Australian contemporary pianist, Zubin Kanga. He treated the audience to a performance of his Dark Twin program, playing Julian Day’s piece of the same name alongside a packed line-up of innovative electroacoustic works, which also appeared in Melbourne’s Metropolis New Music Festival earlier in May and later in Sydney.

The title of Stefan Prins’ Piano Hero for MIDI keyboard and live video refers to the popular game Guitar Hero, but in this case the work utilises MIDI keyboard to trigger playback of samples taken from a video recording of a pianist playing the inside of a prepared piano. The physicality demonstrated by the videoed pianist’s use of extended techniques is juxtaposed against the seemingly still live pianist: large gestures and loud sounds from the on-screen pianist were not matched by the live performer.

Dark Twin, composed by Julian Day and commissioned by Kanga, was easily one of the highlights of the night. Painstakingly workshopped over a period of months, the work begins with a simple idea that evolves throughout. The opening two-note tremolo transforms into a cluster chord that moves throughout the range of the piano and gradually becomes affected by the developing electronics. The electronic part itself is intended to be Kanga’s twin, but as is its nature, proves to be more dynamic than the acoustic baby grand piano in its ability to distort and process the live sound. Throughout, the electronics are subtle and slightly reserved, but ever-present and ominous. Nearing the end, the tremolo descends the range of the piano and the sonic cloud of the electronic part becomes darker and more present in the room until finally receding.

Zubin Kanga

photo Holly Jade

Zubin Kanga

For his composition _derivations, composer Benjamin Carey developed the program that controls its electronics as part of his PhD studies at the University of Technology, Sydney. Similar to speech recognition, it involves detecting a musical phrase once it is improvised, storing the collected musical gestures in a database and then later processing and manipulating them to form the basis of the duet that interacts with the performer’s improvisation in real time. The work was originally composed for solo saxophone and electronics but was premiered in Kanga’s program as a work featuring piano. The concept of the work is interesting; almost like the musical equivalent of a self-saucing pudding, but the accompaniment produced by the program became more of an indeterminable wash of sound as it layered phrases over themselves rather than as an articulate duet.

Transit, by Michel van der Aa for piano, video and electronics, was presented as a live film score—the composer’s Just Before—and his short black and white film, Passage, which follows the plight of an old man who suffers from loneliness but cannot leave his house. The piano score itself was sufficient; it paired predictable musical idioms that are associated with classic horror film scores with quasi-virtuosic piano writing, but the outcome was neither impressive nor disappointing. The film reminded me of student films put together for high school assignments; random and unnecessary camera angles, awkward cuts between scenes and distracting foley soundsnot synced to the video. With only a minute or so left, the film froze, leaving Kanga unable to finish.

Daniel Blinkhorn’s FrostbYte: Chalk Outline utilised piano and electronics to create a soundscape to accompany a video of images from the composer’s journey to the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. It reflects the composer’s concern that climate change is destroying nature around him, the work forming part of Blinkhorn’s collection of electroECOustic works. The piano is processed with techniques used in electronic dance music and dubstep, creating a bassy and compressed electronic accompaniment. The piece was thought provoking: images of glaciers and icy oceans juxtaposed against industrial images—cranes and buildings. As more unnatural images were introduced the electronics became increasingly intense, leaving behind the serene soundscape that was originally established in the beginning of the work.

Cat Hope’s The Fourth Estate “explores the damaging influence that the media can have on all aspects of society” (program note). Hope’s graphic score details the use of e-bows to be placed directly on the strings of the piano, along with a radio tuned to static to be played within the piano. The pianist ‘realises’ the graphic notation through improvisation. The two additions to the piano were intended to interrupt the pianist’s realisation of the score, but the e-bows only created a subtle tone that felt more like a welcome aspect of the work, and at times the radio static got lost within the piano’s sound. The purpose of the radio and e-bows was to obstruct the sound of the improvising pianist, but the work’s performance did not match its political intention.

Lastly, Kanga performed Steve Reich’s Piano Counterpoint in an arrangement by Vincent Corver of the 1977 work Six Pianos. This arrangement features one live pianist, the other five parts being pre-recorded. Piano Counterpoint represents the epitome of minimalism, and its consistent rhythmic repetitiveness proves to be extremely calming. The evolving nature of the work requires concentration and focus and Kanga, considering its length, showed off his technical prowess and the intense musicality and physicality of his playing.

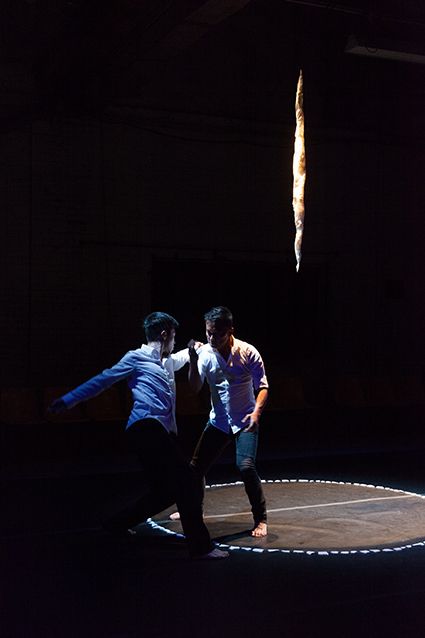

Gentle steps with an open mouth, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Perth iMprov Collective, with Elena Tory-Henderson’s installation Big Yellow

photo Holly Jade

Gentle steps with an open mouth, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Perth iMprov Collective, with Elena Tory-Henderson’s installation Big Yellow

The Totally Huge New Music Festival teamed up with The Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts to host Melbourne-based vocal artist Alice Hui-Sheng Chang. Chang led Perth’s own iMprovisation Collective in a performance around PICA’s black box space before performing a solo concert in the venue’s dedicated concert venue. Both performances were remarkable for their utter commitment and control.

There is a fine line in group improvisation between blending in so much that nothing happens and standing out so much that you become the (perhaps unwanted) focus of the performance. It is to Chang and the iMprovisation Collective’s credit that they were able to control extreme dynamic variations while retaining a sense of unity in the ensemble. The performers began spaced around the first floor balcony that surrounds the central PICA gallery space. I was situated on the ground floor next to Elena Tory-Henderson’s sweeping sculpture Big Yellow. Big Yellow consists of dozens of strips of yellow, unmoulded blister-pack plastic delicately suspended in a broad curve from one balcony of the gallery to another. Part of me was disappointed that Johannes Sistermanns, after his festival-opening concert exploring the tensile strength of clingwrap, was not able to take part in the performance.

The improvisation began with some descending “whoops,” cough-like sounds and kookaburra laughter. As the ensemble passed these sounds in a circle around the balcony, the atmosphere morphed from pointillistic cascades to immense, organ-like chords. The ensemble moved fairly quickly into a bout of blood-curdling shouting. This was a nice touch, avoiding the slow build of many improvisations. The battle cry shouting and screaming resounded very well in the gallery, wrapping the audience in a blanket of bravery. Once downstairs, the ensemble lay, walked and stood around the space, passing sounds to each other more free form and decentralised. Some delicate “sh” and “ch” sounds combined with humming, microtonal beating and the odd violent warbling. The ensemble finished their improvisation lined up in two rows beneath Big Yellow, turning occasionally to send a “whoop” or a shout bouncing around the balconies.

Gentle steps with an open mouth, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Perth iMprov Collective, with Elena Tory-Henderson’s installation Big Yellow

photo Holly Jade

Gentle steps with an open mouth, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Perth iMprov Collective, with Elena Tory-Henderson’s installation Big Yellow

After a short interval, the audience moved into PICA’s black box for Chang’s solo vocal performance. Her vocal explorations originate in the basic principle of breath escaping the body. Between her first barely audible exhalation and her last high-pitched hum, Chang modulates this current of air in striking and unearthly ways. The concert’s staging reflected this simple and elegant performance practice. Black curtains surrounded a stage with a single, broad spotlight and a microphone in the middle of the room.

After several meditative moments, Chang steps up to the microphone and breathes gently, building to a quavering hum. She steps away from the microphone as muffled, squeaking laughter emerges into a deafening nasal tone. This tone becomes the basis for an extended improvisation including a crackling, disintegrating sound like “vocal fry,” but in a much higher register. Chang moves about the space so as to project sound into every corner of the room, even the space under the audience’s seating. She then explores more dynamic, mobile tones, including sounds like a chortling pigeon and a baby crying.

As I Ieave PICA, I sense Big Yellow sweeping silently through the gallery, implying motion in its stillness. Chang and the Perth iMprovisation Collective brought another form of motion to the gallery for a short while, exerting control at the extremes of vocal practice.

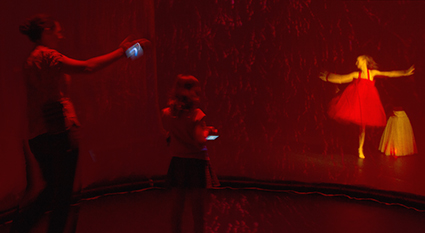

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

photo Holly Jade

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

Totally Huge New Music Festival’s Breaking Out concert showcases work from the state’s most promising young composers. This year’s program included high-quality works ranging from thorny post-serial experiments to loosely structured improvisations and progressive rock epics for saxophone orchestra. The night was made especially enjoyable by the enthusiasm of the crowd, who cheered each work on and off the stage.

In Out Into Stillness, Sally Banyard sets Western Australian poet Kevin Gillam’s “Flotsam and Crows” for alto, piano and saxophone ensemble. The sprung rhythm of Gillam’s poem is half sung and half spoken by Lila Raubenheimer against saxophone chords of gorgeous plenitude. Banyard bases the harmony of Out Into Stillness on Gillam’s line “minor ninth—unresolved.” As the poem moves from the poet’s interior reflections to the ward in which he walks bathed in fluorescent light, the piano strikes up a lively tango exploring chains of sumptuous dissonances.

For his saxophone orchestra composition Octagonal Raven, Sean Bernard promised “a fun and energetic piece” making use of the complex and changing time signatures of progressive rock. He certainly delivered. The Basement Saxx were expertly navigated through Bernard’s tightly packed metric modulations by conductor Matt Styles. The orchestra exhibited tight ensemble dynamics, bringing out the piece’s call and response sections and building tension through vamping episodes before exploding into full-bodied chordal textures.

From the rhythmic excesses of progressive rock to focussed gestural experimentation, Josiah Padmanabham wove three modes of playing across a string trio in Simulacra? The piece included well-crafted solos for each instrument, including a darting violin solo with rapid string crossings and glissandi, a meandering viola solo with left-hand strumming and a wild cello solo with harmonics and tremolos.

John Pax presented the only solo piece of the night, Foreshortening for solo bass clarinet. The piece is an extended exploration of a trilling, key-clacking motif which is transposed and articulated across the instrument. Clarinettist Gareth Hearne sustained an intense sense of focus as he voyaged across the whispering score.

Laura Halligan’s Desperada superimposes minimalist electronics and gritty violin amplified through a piezo transducer. Operating the electronic part, Halligan develops a sense of urgency through loud and unrelenting rhythms. Violinist Pippa Lester plays a series of escalating motifs, from single pizzicato notes to raw scrubbing.

Traced Over for guitar and electronics is an exploration of the spectral profile of a bowed acoustic guitar. The guitarist’s gestures (played by Jameson Feakes) are electronically echoed and amplified by the composer James Bradbury. As the piece progresses, these echoes become more heavily modified. As Feakes bows the guitar more roughly, the sounds become harder for the electronics to identify and modify. By contrast, the piece ends with some of the purest tones possible on the guitar: an EBow resonating a string with some wonderful punctuations of plucked strings above the nut.

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

photo Holly Jade

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

Two guitars conjure an abandoned house explored by composer Olivia Dawes in Derelict. The devastatingly quiet and slow composition brings to mind the stillness of long-forgotten places and nostalgic echoes of the past. Preparation of the guitars with paperclip, bobbypin and pencil produced an array of buzzing, swelling and decaying tones that were combined with folk-inspired fingerpicking patterns out of an American-gothic film score.

Josten Myburgh—who deserves an extra vote of thanks for organising the concert—presented his New-Complexity-inflected piece Doctor for soprano, two percussionists and electronics. Myburgh sets up the expectation of a large-scale dynamic gradient such as “soft to loud” in his program note, only to humorously subvert it by playing a minute of ear-splitting noise and dropping right down to silence. As soprano Sarah Cranfield, dressed all in black with thick-rimmed glasses, repeats a staccato “chi-chi-chi-chi,” the theatrical piece begins to resemble Ligeti’s Le grand macabre, with Cranfield as Barbara Hannigan. Myburgh makes good use of the two vibraphones, with beguiling bell-tones forming a shifting bed under Cranfield’s vocalisations. Percussionist Thomas Robertson turns away from the vibraphone to occupy himself with two recent staples of new music percussion: cardboard box and Styrofoam, both played with a bow. These effects should be employed sparingly to avoid redundancy, but when used, it should be vigorously. I was sad to see the styrofoam completely intact and the edges of the box barely dented at the end of the performance. The percussionists then began a section with brushes playing staggered rhythms on toms, an excellent effect susurrating underneath Cranfield’s vocals.

Elise Reitze’s Tom Bomb should win an award for best program note, which consisted of a single bomb emoji. The piece was a choreographic riot worthy of Taikoz. Three percussionists are spaced around a bass drum, playing with the backs of drumsticks. Together they make complex rhythms, occasionally playing ‘Mexican waves’ and breaking the air with cracking rim shots. One player has a weight on the drum near him, adding light and shade to the drum’s tone. The performers move onto smaller toms, playing with their hands. The piece builds to a climax, the performers raising their sticks high above their heads.

Ben Christiansen takes Albert Camus’ novel The Plague as a point of inspiration for Carousel for two saxophones, two percussionists and piano. Or at least, he takes as inspiration the character Joseph Grand, who wants to write a novel but is such a perfectionist that he cannot get past the first sentence. Christiansen’s stuttering piece similarly struggles to get going. An opening attack is restated over and over again in different ways, with trills, tremolos, different dynamics and meters. And yet, unlike Grand’s novel, somehow a work is made. A very satisfying and enjoyable work, even. Just as the piece never really begins, the ending is also ambiguous thanks to an excellent performative gesture by Christiansen, who also conducted the piece. He suddenly drops his arms and turns for a bow as though he had just decided that enough is enough.

The final work of the evening raised the performative stakes with a homage to the Perth-based performance artist and lo-fi folk-pop singer Agamous Betty. Betty was kind enough to participate in this homage, performing Maddington Laundry in a delightful range of orange-red pastels and crooning out the indecipherable lyrics of the mournful song. Meanwhile, Woolley prepared a table-mounted guitar and played recordings through a hand-held tape player as Betty mimed along. Woolley also produced crunchy poppings by rubbing a metal ruler over the pickups (turn down your amp first if you want to try that one at home).

It was encouraging to see the level of mutual support between the young performers and composers in the Breaking Out program, as well as hearing the command with which the composers wielded their diverse musical styles.

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

photo Holly Jade

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

Eleven young composers showcased their work in an immensely varied program, Breaking Out. First was Sally Banyard’s pastoral Out Into Stillness which brought new life to Western Australian poet Kevin Gillam’s text via an alto singer and an ensemble of 10 saxophones and piano. An evocative piece, it shifted between layers of thematic material and touched on allusions to popular music, jazz and tango.

The colours of the saxophone orchestra complemented Gillam’s text well and gave the work a sense of storytelling. Banyard demonstrated a fine feel for orchestrating the ensemble, blurring and swelling chords between different parts and letting melodies unfold naturally through the ensemble.

The saxophonists remained on stage for Sean Bernard’s catchy Octagonal Raven, a lively work with a very cinematic feel. Sections of fast paced compound rhythms and melodic interaction between parts were interspersed with rich and sonorous moments that beautifully captured the resonance of the ensemble, though perhaps the orchestration felt a little over-saturated given the brief duration of the work and could have benefited from being scaled back for some moments of respite.

One of the highlights of the concert was Josiah Padmanabham’s Simulacra, a string trio that captured extended techniques and implemented them gesturally to create a very visceral work. It had a perfect sense of pace, drawing the audience in closely for intimate moments and allowing the sound to organically unfold outward. What I especially loved about the composer’s writing was that the ensemble felt entirely cohesive, the music flowing between the three instruments interactively and combining to make a very clear and rounded rather than disjointed sound. Padmanabham’s use of extended techniques reminded me of the work of Finnish Composer Kaija Saariaho, who also works closely with extended string techniques and quite similar spectral sound worlds. One of the dangers of this kind of music is that it can become too driven by special effects and gimmicks, but this work steered clear of cliché to deliver a beautifully sinuous and satisfying sound.

John Pax’s peculiar solo for bass clarinet, Foreshortening, focused almost exclusively on exploring the possibilities of breathy, fluttering sounds, drawing its tension from silences. The work brought the listener in very closely to its narrow subject matter in a way that meant even very small changes in texture made for moments of impetus. Pax only allowed a few brief moments for the sonorous bass notes to emerge and in doing so rendered these moments, near the end of the piece, quite satisfying. One has to admire Pax’s compositional bravery and commitment to exploring this sound world.

Laura Halligan’s theatrical Desperada for violin and electronics immediately called to mind the ferocious string writing of Bernard Herrmann, blending a vicious violin sound with electronics and a relentlessly thumping bass. Perhaps the work could have benefited from more live input in place of predetermined sound, but nonetheless made for an immersively creepy piece.

James Bradbury’s Traced Over for guitar and electronics began with the haunting sound of bowed guitar strings, which was then spatialised and manipulated. Over the course of the work Bradbury developed a very immersive sound world by working with spectral data from the guitar. In his program note he describes how he aimed for a rising complexity in the guitar’s material to confuse the electronics and bring a disparity between the two areas of timbre. It was a little hard to actually hear this change as I thought most of the development was derived from harmonic and dynamic changes rather than timbral ones, but it was nonetheless an interesting concept to explore.

After a short intermission, two acoustic guitarists took the stage to perform Olivia Davies’ Derelict, which explored a very sparse, dry sound world. Davies utilized a combination of effects from foreign objects such as a pencil and a paperclip to interfere with the strings, as well as tapping the body of the guitar. Though the piece took a while to get going, once it did Davies used repeating motivic cells to build a very convincing ‘derelict’ atmosphere and demonstrated a fine feel for rhythmic impetus.

Josten Myburgh’s Doctor for soprano, two percussionists and electronics dealt with an unusual sense of temporality. The work began with an assault of unbroken, harsh noise followed by a snap to a period of silence that just nudged the boundary of awkwardness, and then introduced acoustic material. Myburgh blended the sound of two vibraphones beautifully with an electronic texture of soft crackles, high pitched frequencies and a gentle spectral glow, contrasting this quite pleasant texture with interruptions from a cardboard box full of metal objects. He also called for a piece of styrofoam to be bowed, an assault on the ears that I can probably never forgive. A combination of the slow pace and mostly high pitch of the soprano line made Josh Wells’ text a little hard to discern, making it feel a little superfluous—perhaps a missed opportunity. Nevertheless, Myburgh commanded the audience’s interest through his use of blunt jumps and quick juxtapositions, and there was a certain feel of timelessness to long periods of unchanging texture. It became the sort of piece that you could get lost in and not be sure whether you had been there for five or 20 minutes.

Tom Bomb by Elise Reitze was a short and funky piece for three percussionists. It seemed quite presentational, almost ritualistic, asking for the three drummers to huddle around a bass drum and calling for visual effects such as a Mexican wave of the six hands on the drum. It focused on continually introducing small rhythmic elements to a continually expanding texture, Reitze using the rhythmic momentum generated to build to some very satisfying climaxes.

Ben Christiansen’s quirky and disjointed Carousel drew us in to quite a sparse sound world. The ensemble of two saxophones, vibraphone, marimba and piano seem to blurt out different gestures interspersed with periods of silence. It felt like it had the potential to go somewhere but instead just sat on its material, and perhaps that’s all it really needed to do.

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

photo Holly Jade

Breaking Out Young Composers’ Night

Last on the program, Drew Woolley and Agamous Betty performed Maddington Laundry. Woolley in a corner playing electric guitar drew us into quite a dark, melancholy world via distortion and processing of several electric guitar effects, while Agamous Betty sang a gloomy down-tempo tune. This is a work that one would probably describe more as performance art, coming to a cathartic end and transforming into a more acoustic conclusion.

Friedrich Gauwerky

photo Holly Jade

Friedrich Gauwerky

With his Amour–Soundbridge concert, cellist Friedrich Gauwerky ranged widely across the contemporary cello repertoire while exploring the musical ties between Australia and Germany. Gauwerky himself embodies these ties, having lectured in cello, chamber music and New Music at the Elder Conservatorium of Music in Adelaide in 1989–96. He also performed as principal cellist in the Australian ensemble Elision in1990–97.

Gauwerky’s artist’s note pointedly states that “[h]e is a free spirit who knows no national preferences and who feels equally at home in England, China, America and far-off Australia [haha] as he does in his home-town of Cologne.” The Amour–Soundbridge program is less an exploration of international ties than a positive statement of national boundlessness.

Msistlav Rostropovich commissioned Hans Werner Henze’s Capriccio as part of a dozen works for the 70th birthday of the Swiss cellist, conductor and impresario Paul Sacher in 1976. The piece, full of dramatic and structural conceits, including pitch material derived from the letters of Sacher’s name, depicts theatrical scenes, opening with guitar-like pizzicato chords under a sinuous melodic line. Gauwerky imbued the piece’s second movement with an incredible sense of urgency, the leaping melodic line interspersed with moments of double-stopped counterpoint.

The German-born composer Thomas Reiner studied under Henze before moving to Australia, where he now lectures at Monash University. Like Henze, he could not resist the cello’s lyrical capacity. His Three Sketches for solo cello begins with a singing movement utilizing the full register of the instrument. Reiner contrasts this lyrical movement with a grittier one utilizing double-stops and sul ponticello scrubbing. The third movement consists of pianissimo tremolo and light harmonics. These certainly are sketches of the most characteristic modes of the instrument. It would be interesting to explore how they are fleshed out in Reiner’s later chamber works.

If Henze and Reiner’s compositions inherit the cello’s romantic modes of expression, Klaus K Hübler’s opus breve pulls them apart through “action notation.” A kind of tablature separately indicates the bowing, fingering and string to be used on three staves. This form of notation is quite space-intensive, requiring three A3 pages for a piece only a minute and a half long. The benefit of “decoupling” bowing, fingering and string-use in this way is that one can notate complex gestures where each component of the sound moves independently. For instance, Hübler uses trills that are only partially sounded with the bow. Gauwerky emphasises the silent moments of these trills with percussive finger action, while the bow line utilises a range of effects including ricochets at the tip and intense scrubbing. Gauwerky somehow coordinates this ambidextrous explosion of energy.

In comparison with Hübler’s technical virtuousity, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Amour is a heartfelt, naïvely beautiful outpouring of emotion. Originally written for clarinet and dedicated to one of the objects of Stockhausen’s affections, it was intended to be playable on any melodic instrument, but Stockhausen did not produce a version for cello during his lifetime. Gauwerky arranged it for cello in 2014 in cooperation with the publisher Stockhausen-Verlag. The piece sits so comfortably on the cello that it is hard to believe it was written for any other instrument.

Amour consists of three movements: “Cheer up,” “Your angel is watching over you” and “A little bird sings by your window.” The opening movement is comical, presenting a modal melody that occasionally explodes into angular chromaticism. The second movement alternates a low, lamenting voice with a higher, faster one. The two voices move closer together until they intermingle at the end. The birdsong of the final movement erupts with agile voices across the whole range of the instrument. Gauwerky gave the piece’s final, heartbreaking melody all of the space it needs, breathing deeply between each phrase.

Felix Werder escaped Nazi Germany in 1940 and settled in Melbourne, where he exerted an incredible influence upon Australian musical life until his death in 2012. His Violoncello Solo 1 is a whirlwind of distinct gestures, each beautifully crafted. The piece requires one to give in to the torrent of gesture and forego structural listening. Is this what Gauwerky meant when he said that there was “something very Australian in it”?

Volker Heyn’s Blues in B-flat is the bleakest work for cello I have ever heard. The composer moved to Australia from Germany in 1979. After studying at the Sydney Conservatorium, Heyn worked in a metal factory, the sounds of which Gauwerky likes to think still resonate throughout his music. The “Blues” of the work’s title is to be understood as a “cry of rebellion and despair.” The cello uses a scordatura, or retuning, of three strings in B-flat and one in F. Beginning with shocking sforzandi on two strings, the piece proceeds as a succession of drones including sung pitches, strings played past the cello bridge and drones played with two bows at once. Gauwerky seamlessly introduced and removed a mute from the bridge, smoothly changing the timbre of the drone.

After this incredible tour of Australo-German cello music, Gauwerky returned to where it all began: Paul Hindemith’s Sonata for Violoncello Solo. An encore of the cello solo from Stockhausen’s “Wednesday” from the opera Licht was an unexpected and welcome surprise. The Totally Huge New Music Festival has truly fostered a concert of “cultural significance,” giving Gauwerky the opportunity to share his unique long-term perspective on contemporary Australian and German music for the cello.

For its 117th instalment, Tura New Music’s historic Club Zho program returned to the Totally Huge New Music Festival to present new music and sound art in a semi-formal environment, this time invading Jimmy’s Bar in Perth for a concert of escalating volume.

Hedkikr

photo Holly Jade

Hedkikr

Bass clarinettist Linsday Vickery and percussionist Darren Moore performed as the duo Hedkikr. Despite the name, the duo was a picture of refinement and grace. Moore used his drum kit sparingly, focussing on a restricted palette of techniques. Moore bowed cymbals while Vickery drew contorted lines from the clarinet’s middle range. Moore settled into an extended exploration of the zinging and humming quality of wooden sticks on cymbals. Even quieter, he rubbed styrofoam on a snare skin, while barely activating the kick drum. The set felt like an exploration of wind and air, with Vickery’s whistling, breathy reed-sounds combining with Moore’s susurrating percussion.

Bassist Cat Hope and Vickery defied all expectations of a polite classical duo. Performing under the moniker Candied Limbs, the 20-odd minute set was an explosion of irrepressible energy. Vickery multiplied his bass clarinet into a hellish chorus through a Max/MSP patch, while Hope called upon the power of a dozen vintage effects pedals. She successfully channelled some talk-show material from a hand-held radio through the pickups of her bass guitar, while Vickery created a sound with his patch like the squealing of a thousand dying spiders. After more such pyrotechnics, including attacks of ground-shaking bass and deafening feedback (I was glad I’d brought earplugs), the duo developed a masterful texture combining a bed of ambient sound with a clean clarinet tone moving within. The focussed clarinet modulated into a series of 8-bit computer-game-like tones before dissolving back into the pure, unadulterated bass hum. A more atmospheric episode followed, during which Hope’s growls and screams would have made Dario Argento proud. Vickery took the set out with an impossibly high, pleading tone.

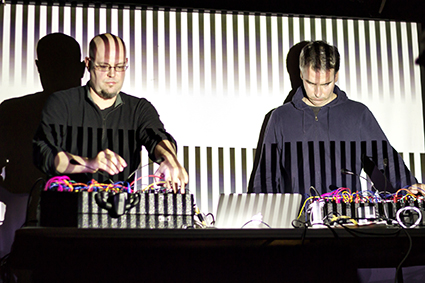

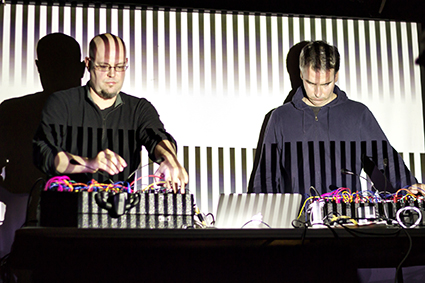

Black Zenith

photo Holly Jade

Black Zenith

Singapore-based modular synthesis duo Black Zenith (Darren Moore and Brian O’Reilly) conjured a staggering array of sounds and textures from their rats-nests of patch cables. While understanding the principles of sound synthesis and being on nodding terms with its most common sonic results, I must admit complete ignorance of the artisanal world of modular synthesis. This may be for the best, considering that some readers of this review will also be in the dark. Modular synthesis is performed through a rack of analogue synthesiser components, many of them hand-made, which are selected and installed by the performer. These components perform discrete functions, such as producing, filtering or changing the envelope of tones. Their inputs and outputs may be patched or redirected to the inputs and outputs of any other module. According to my music technology consultant Steve Paraskos, the difficulty of modular synthesis is not getting a sound going, but shaping the sound and modifying one’s patch in a live setting, a process that requires tactile finesse.

Prior to performing, Moore and O’Reilly spend considerable time modifying their patches in order to establish a sound-world rich in contrasting and complementary possibilities. A performance is then an opportunity to dynamically react to one another, co-navigating this sound world through their respective patches. The range of sounds that Black Zenith produces is absolutely bewildering. Finely textured tones coexist alongside pure sine-waves; dry clicks give way to resonant, drum-like attacks; overlapping waterfalls and burbling brooks transform into wavering, alien ambience. Then there are the metaphor-defying sounds known by onomatopoeia and obscure addresses among the patch cables.

From whispering brushes on snares to sounds so loud they are felt more than heard, Club Zho 117 presented a dynamic portrait of contemporary sound and noise art. Black Zenith’s perpetually unfolding sonic repertoire was an inspiration to all present.

These reviews are the result of a RealTime intensive, first-stage writing workshop for four participants held 1-3 May in Albury-Wodonga in conjunction with Murray Arts and HotHouse Theatre and conducted by RealTime Managing Editors Virginia Baxter and Keith Gallasch.

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Kate Rotherham: Poets In Trouble

A gigantic concrete pipe, reinforcing mesh protruding from its smashed edges and two broken chunks scattered at the forestage, is revealed through a smoky haze. There’s an almost apocalyptic feel as teenage Chloe, in cut off denim shorts over black tights with a checked shirt tied around her waist, saunters onto the stage and hits the audience with a bold torrent of rapid-fire shards from her life. We are instantly pulled into her world and held there in her unflinching gaze.

Chloe (Matilda Bailey) is new to this dead-end town, brought here unwillingly by her emotionally absent mother who has moved in with yet another new boyfriend. Beneath Chloe’s tough exterior lies a complex collision of physical, social and educational disadvantage and a well of unmet needs. Her edgy displacement comes on top of her oceanic grief for her dead father. The ying to her yang is Chris (James Smith), classmate and slightly less-wounded poet. They fall in love against a pervasive backdrop of bullying and hardship and search for a way out.

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has said that she dislikes both the direct nature of language in theatre and the usual delivery of poetry (Time Out, Sydney, 21 May, 2013). Her unique solution is to keep the language fast and tight where the characters reveal themselves to us in gutsy poetic bursts. Chloe’s jagged self-reflections give voice to her bleak inner world. Her dialogue is an energetic mix of flashbacks and present realities with words cleverly substituted for sound effects: “Pad pad, pad to my room.” Chloe shares every thought, mood and movement with us, drawing the audience deeply, and sometimes uncomfortably, into her dark and chaotic life. We watch for signs of hope to sneak in through the cracks as she explores the potential catharsis of Chris’ love.

Walshe offers us kaleidoscopic fragments of language and character to piece together as we can. There is a deep love of language at the heart of this play, challenging us to listen carefully for subtle changes in whichever of the two characters is telling the story. We must stay alert and gather the clues before they scatter and are lost. On top of the internal thoughts and verbal sound effects, the characters question and answer themselves, simultaneously quoting teachers and parents and school bullies. There is a pulse to the language; it is instantly evocative and powerfully rhythmic. After some measured praise from her mean teacher—who’s also Chris’ father—she says, “He’s taking the piss. If he’s taking the piss I will hang myself from his front door. He’s not taking the piss out of me. I stare out the window, watch kids playing handball. I am quietly, quietly, and I hope you’ll keep this one on the down and low. I am quietly bursting with joy.”

Initially Chris and Chloe observe each other, orbiting each other’s worlds while speaking in parallel snippets directly to the audience. As their relationship develops their dialogue also becomes more connected and more directed towards each other. At the high point of their brief union they speak to each other, facing to face as the armour on both sides falls away, before being rebuilt. It’s a cleverly choreographed dance of text, personality and plot as the performers inch closer to themselves and each other.

For all its energy and momentum, the play carries a heavy sense of stasis. Chris and Chloe are locked into this hostile town in the same way their parents are locked into their dysfunctional relationships. Chloe condenses it to its essence when she says, “There’s a place here in the conga line of listless souls with my name on it. Reserved me a seat and everything. Where we live while you hate us.” There is a gnawing sense that nothing can improve here and any possibility for new beginnings will need to be sown elsewhere, far away from here.

We see their decaying family lives up close. Chris’ bullying father and alcoholic mother are a particularly ugly combination of regret and disdain. There’s almost inevitability about the violence between Chloe’s ineffective mother and her new man. Chloe retells it as, “Crash. Oh no! Here we go. Mum spilt the coffee on the lino. Hear them in the kitchen start the funeral march. I’m sorry sorry Brian.”

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has cast her thematic net wide in a layered play about struggle and identity with domestic violence, grief, bullying, emerging sexuality, disability, learning difficulties and disadvantage masterfully woven into the narrative. There is a unique poetic brutality to Chloe, and we glimpse the exposed scaffolding of her vulnerabilities as she shifts away from her default defiance. In one especially powerful scene she is forced to read in front of her class and as she stumbles and falters with her reading we see her bravado fracture. All too aware of her shortcomings she will later ask the well-read Chris, “What’s a poet got that a dyslexic can use?”

Matilda Bailey is superbly sure-footed as Chloe, striding seamlessly along the wide spectrum of internal and external thoughts and moods. We watch her crack open and close over again, as her grief simmers ever closer to her fragile surface. James Smith skilfully takes the character of Chris on a transformative journey from the slumped, painfully shy “Odd-Boy” in his over-sized jumper to an increasingly confident boyfriend who dreams of rescuing “Chloe of the Underworld” from her tormentors and perhaps from herself. The brilliant duo has been expertly directed by Jon Halpin in this complex and densely-packed performance.

Andrew Howard’s musical score of subtle bass booms and intermittent chimes works below the surface, letting the poetic, at times frenzied, text carry the story unimpeded. Scott Howard’s changes of colouring highlight postural shifts, allowing us to zoom in on Chris and Chloe as they circle each other, and any possible future they may have, around the broken pipe.

This Is Where We Live is a beautiful poetry-slam of identity, violence and neglect with a swirling undercurrent exposing the darker truths inherent in staying where you are.

Kate Rotherham is a writer living in north-east Victoria. Her award-winning fiction has been published in magazines, journals and anthologies, including The Best Australian Stories. Her short plays have been performed locally and in Sydney and on the GoldCoast. www.katerotherham.com.au

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Ruby Rowat: Hit me

We’re in the derelict gutter of a desolate underworld. A disused storm-drainage pipe, nearly the size of a caravan, sits burst, grounded on the stage, its jutting steel latticework brutally exposing random jagged ends. A sense of congestion; violently displaced flow. Two hunks of the concrete pipe, steel skeletons awry, have conveniently landed either side of the pipe which is big enough to run through, but, like the harsh, thwarted life of teenager Chloe (Matilda Bailey), there is no flow; no clear route to follow.

We are thrown into Chloe’s reality; it’s her play, the text is her story, miraculously containing all the brittle shards of her life. There is nothing soft or caring in this world. We are put on edge and held there by the masterfully crafted, densely metaphored, race-pace poetry of the script. This barrage of dexterous language demands our attention. There is no rest. No pause. Chloe’s unstable victim mum, sustained constant and irregular humiliations, jabs of physical threats and violent hits. Constantly on the move, new town, new abusive man. Everything seeps into and disrupts everything else, so Chloe’s unsafe home life is right with her in the high school classroom, sabotaging her potential brilliance. There is an adolescent strength and defiance in her character: she is at once a verbosely articulate, self-aware all-seeing know-it-all in her personal narrative, but shattered when she’s put on the spot in class and can barely string together syllables.

Chloe’s “I hear them in the kitchen start the funeral march” sets up the inevitable violence about to transpire. When she’s hit by her mum’s boyfriend, her sense of “…I know where I am. …This is intimate,” was initially foreign, even repulsive, until I related it to the excruciating pain of aliveness when a loved one dies. Definitely a disturbing shock for the audience in this pivotal moment.

Chris (James Smith) brings with him a whole other brand of familial dysfunction, along with a degree of respite from frenzy, with the more measured pace of his delivery. Another, if less wounded poet, an “Odd-Boy” awkward introvert, Chris’ romantic imagination posits Chloe as a limping heroine, a Eurydice for him to rescue. Without specifying the cause of her disability, he describes the limping Chloe as “my one-legged bovine” and her schoolmates taunt her with “spina bifida, spi spina bifuda.”

The clever use of third person pronouns as Chloe and Chris speak of each other, even as they relate in real time, sets up a self-reflective distance between them, in contrast to their emotional proximity. Similarly, their physicality is akin to capoeira dance, without the acrobatics; mostly, they don’t make actual contact. The one time they do hug, it’s that much more powerful.

Rural images—”one legged bovine,” “strictly bucolic,” “classmates in the cattle yard,” “out to pasture”—grimly locate the characters in a regional town. But in a beautiful night-sky moment, Chris lounges against the storm-water pipe, as if leaning against a haystack in a field, while Chloe, at a distance, is lit such that her shadow lies next to him. A deftly woven contrast: fantastic tranquility transposed onto the stark reality of the contorted gnarly pipe and the daily havoc of the teenagers’ lives.

We learn that the “river hasn’t flowed here for three years.” Despite the torrential pace of the performers’ delivery, we are struck by an overall sense of stagnation. Hope is won incrementally. I was initially a bit confused at the abrupt ending of the play. However, given a chance to reflect, the last scenes undeniably move toward healthy prospects coming from a final distressed desire for interaction—”Swivel”, Chloe pleads, across the vast psychological distance from one side of the stage to the other where Chris sits, never turning to look—to an easeful reading of a poem that (finally) acknowledges her father’s death. Then she tells us, “Railway sleepers stand where my spine used to be.”, revealing, metaphorically, that it’s as if an operation for her deformity has straightened her out, allowing her to escape, ultimately to flow: “The train arrives, passing thru my body.” She is transformed: “My whole body shakes…And I’m not afraid. Of what’s coming,” releasing us from the play’s anxious stranglehold into an optimistic potential for life.

Matilda Bailey’s mastery of Walshe’s language is matched by her gestural agility. Each lighting cue, every shift in the script, is accompanied by succinct adjustments in body language. James Smith’s expertise is evident in the unfurling of his hunched-over posture during moments of love or when he strides atop one of the shards of concrete, bright light delineating for us an iconic image of a soldier’s heroic stance, his body and arms all action. Andrew Howard’s spare pulsing music sustains intense emotional moments.

I enjoyed Walshe’s graphic imagery in a script that obliges its audience to constantly connect the dots in order to keep up with the action. The theatrical possibilities offered by the huge storm pipe aren’t fully exploited to inscribe clear movement patterns through and around the tunnel, or atop it to evoke the risk frequently indulged in by teenagers. However the set design certainly magnified a sense of major societal failings and the jarring personal violence tackled in This Is Where We Live.

Now based in Albury, trapeze artist Ruby Rowat toured internationally from Montreal for much of her life. She has also coached across Australia, Canada and Brazil. She continues to perform partner acrobatics on the ground and in the air as she begins to broaden her exploration into voice, rhythm and writing.

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Ann-maree Ellis: In the flood of fear and grief

Twisted and rusted exposed steel formwork protrudes from a large, broken concrete storm-water pipe. Haze and downlights thicken the atmosphere, receding to blackness beyond the pipe. This is where we live: the abandoned back blocks of a regional town. Stagnancy and neglect are palpable.

Chloe (Matilda Bailey) bowls in wearing cut off shorts, black stockings and Doc Martens. A torrent of words flood the derelict space, at once aggressive, poetic, relentless. Very quickly she sketches a picture of her dysfunctional working class family and the familiar angst of adapting to another new town, another new school. I take this in, yet at the same time am not entirely sure what is happening. I’m put off kilter by the barrage of words, directed at the audience, that move a little too fast, range too wide, leave too many gaps.

Straight away we’re put on notice to pay attention, keep up. There is no silence, no stillness of mind, when even pauses are verbalised (“pause pause”) and sound effects are spoken (“gravel gravel, crunch crunch, pad pad”) amid a rush of words that simultaneously convey the inner and outer worlds of Chloe and her new ‘odd boy’ friend, Chris (James Smith). In a continuous stream of poetic language, delivered without apparent punctuation, the two vividly create scenes and an invisible cast of characters. We are hit by the density of their heightened awareness, the fullness and intensity of teenage experience as Chloe and Chris verbally unload their universe on us.

A rather bleak and disturbing universe it is too. When Chloe intervenes to prevent violence to her mum and takes a hit from the drunkard boyfriend, she brazenly confides, “This bit’s hard to explain. You’ll find it in the white trash DNA… When his knuckles make contact I just about cum.” Later she observes the inevitability of hopelessness surrounding her: “There’s a place here in the conga line of listless souls with my name on it. Reserved me a seat and everything. Where we live while you hate us. Where we really live.”

Chris, somewhat awkward and introverted, might seem to have greater opportunities: educated parents, art adorning the walls. But his derisive, controlling father, Donald, and his ‘juiced up’ mother reveal only coldness and bitterness at home. Donald is hard on Chris. He also happens to be his and Chloe’s school teacher. Chloe provokes his disdain at the outset, and Chris can’t measure up to his lofty standards. Donald’s power to either facilitate or hinder their self expression, both as budding poets and young adults, is stark when he helps unlock Chloe’s dyslexic block so she can read aloud, while simultaneously slighting her with his choice of a puerile, sexual limerick.

Navigating plot points within Vivienne Walshe’s dense text is a challenge. Chris and Chloe take turns delivering passages in rapid fire. In a collaged and layered way, they play off one another, picking up on the others’ lines with parallel utterances, yet rarely speaking directly to each other. They engage physically, yet the address is mostly direct to the audience. The poetic phrasing and shifting roles mean at times it’s not clear whether something is past, present or future, metaphoric or imaginary, first or third person.

Just as the audience is kept on their toes, Bailey and Smith are put through their paces as they deal with the momentum and multi-directional nature of the language. While not quite as obviously demanding, the direction and the actors’ physical embodiment of the characters underscores the complex weaving of language. Bailey’s twitching and jutting punctuates Chloe’s outpourings, delivered with an entire physical lexicon full of protective, cultivated and unconscious behaviours that encapsulate her sassy attitude.

As with Rob Scott’s lighting, which changes colour and tone in subtle yet decisive shifts, Andrew Howard’s soundscape is a subtly visceral presence that precisely hits the mark. Seeping in and out, it rises and recedes beneath the voices; an atmospheric bass beat, ever so slightly increases in speed and volume with the emotional intensity of the scene. Neither invisible nor dominant, each of these elements is absolutely integral in creating the perfect conduit for Walshe’s flood of words.

This Is Where We Live is taut, beginning to end. I remained on edge all the way through, engaged by masterful performances and drawn in by poetic dialogue, yet pushed back by its sheer density. I’d have liked more space to appreciate the fullness and complexity of the text and absorb the issues raised. It’s a challenging work that expresses difficult themes.

Reprieve did come, albeit not in a way that could be fully comprehended. If the distressed concrete pipe, solidly central to the action on stage, suggested fracture, then the final image of Chloe breaking through her grief and fear gave a sense of her coming to terms with the emotional and psychological obstacles she must face. I, for one, needed this cathartic end. It seemed that something had to snap in Chloe’s psyche if we were to be given any breathing space in a stultifying narrative that was largely hers.

Ann-maree Ellis lives in Albury where she coordinates the annual literary festival, Write Around the Murray. For many years she maintained a performance practice in dance improvisation and was a founding member of the Melbourne-based improvisation collective, The Little Con.

Matilda Bailey and James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey and James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Sally Denshire: In the gutter looking at the stars

A shattered concrete storm-water pipe big enough to walk through with skeletal rusting wires exposed evokes a sort of underworld. Chunks of pipe litter the forestage. Composer Andrew Howard’s intermittent bass reverberates through the haze and Rob Scott’s restrained lighting underscores the fluctuating moods in this two-hander in which Chloe and Chris psycho-dramatise their roles of others in addition to their own.

Into this alien landscape stalks 17-year old Chloe (Matilda Bailey) in Doc Martens, tights, cut offs and t-shirt, green-tipped hair and a red checked shirt tied round her hips. A young woman who has been scarred by parental abuse Chloe can experience self-hatred. “Hit me,” she says to her mother’s boyfriend interrupting him doing violence to her demoralised mother. The beating generates a perverse intimacy: “When his knuckles make contact I just about come,” she admits. Chloe speculates that this kind of sexual arousal could “do a girl damage.” As she says, “This is bad. This is bad for my health. What happens to girls with this kind of appetite?”

Her “Odd-Boy” boyfriend Chris (James Smith), who initially describes himself as “a flea on the arse of fresh road kill,” sits with his back to the audience in a dark, baggy jumper, jeans and runners. His body seems almost an afterthought, even though Chloe will later admire his “real six-pack.” The anonymous son of Donald, the pairs’ pedantic, caustic schoolteacher, Chris sets out to rescue the limping, proud “Chloe of the Underworld” from her bullying stepfather and this “one highway” town where people eke out an existence.

Chloe and Chris each voice hopes repeatedly dashed by the brutality of their classroom (where the teacher ineffectually tries to erase a cock and balls drawn in permanent marker on the whiteboard) and their respective damaging family lives. After the beating Chloe avoids school because of bruising on her face. When she asks, “Janelle, have you noticed anything different about me?” her mother “looks up from the crossword, squinting. ‘Have you done something with your fringe?’” “I haven’t been to school for a week,” her daughter retorts.

A yawning psychological distance separates Chloe and Chris and, for the most part, each faces the audience in turn, rather than looking at the other. Gradually they become closer, brothers in arms, momentarily bonding.

Rhythmic bursts of language coalesce as a perfectly formed jewel of brilliant poetic utterance in Vivienne Walshe’s This is where we live. When Chloe’s Dad was alive he had said, with a nod to Keats’ notion of negative capability, “be that thing…what you are looking at, or what you can hear, be that thing and you can disappear. You can go anywhere!” In similar vein, the pair of likely symbolist poets watches a crow up in the sky “fly like it means something more.” When Chris announces “my fantasies are strictly bucolic,” he sounds as if is parroting his teacher-father. Gentle laughter ripples through the audience. When the teacher, supposedly being supportive, expounds on the value of “compact little units of verse, is he actually eroding his students’ confidence to write?

Walshe uses the language of disability and physical difference metaphorically rather than as fixed, diagnostic labels. In the playground, healthy ‘skanks’ repeatedly taunt the limping Chloe to the beat of “Spina bifida, spi, spina bifida.” Chris plays with the idea that Chloe moves differently, describing her vulnerability as “polio dancing with a wayward leg” while Chloe ironically predicts she will end up “dancing for the blind.” But, as she walks with Chris with the same stride, “for the first time in my short order teenage wonder life I walk to class with an even gait.” Sound effects are spoken aloud such as her terminally ill Dad’s “cough, cough,” the “pad, pad” of parental feet on carpet and the “gravel, gravel” of moving around outside. Persisting with medical discourse, in a moment of breakthrough coming to terms with her Dad’s death, she chants the syllables of “me-so-the-li-om-a” (the asbestos-related condition that killed him) in a poem she reads aloud to her class.

Chloe’s scream after reciting the poem exorcises her past and heralds psychological individuation as she struggles to break free from paternal violence and maternal neglect. Will she escape this alien ‘back water’ where she lives?

Chloe and Chris are damaged young people “lying in the gutter…looking at the stars” (Oscar Wilde). Vivienne Walsh has crafted a poetic and multi-layered coming-of-age drama that—as well as offering insights about the young for older audiences—should resonate in particular with the disaffected young who love rap or poetry spoken aloud.

Sally Denshire is an Albury-based writer with 20 years experience in academia. Thirty years ago she established the Youth Arts Program at Camperdown Children’s Hospital in Sydney. Most recently she has published (auto)ethnographic tales of youth occupational therapy practice. Sally is an Adjunct Lecturer, Charles Sturt University, and on the organising committee for the Write Around the Murray Festival.

George Brandis

In a breathtakingly audacious, meticulously planned and utterly unanticipated 2015 Budget caper Attorney General and Minister for the Arts Senator George Brandis has plundered $104.7m of Australia Council funds to establish The National Programme for Excellence in the Arts in his own Ministry which, bizarrely, already includes an Australia Council committed to excellence. Now Brandis has two major funding bodies—one at arms-length and one close at hand, where artists will line up for a Brandis (recall the uproar over the Keatings).

What was Brandis’ motivation and how did he maintain secrecy? While fellow ministers loudly broadcast their intentions in the weeks leading up to the ‘fair go’ Budget day, this minister said nothing and went in hard with 2014 Budget gusto when the time came. Press reports say the Australia Council CEO Tony Grybowski, with Brandis at the opening of the new Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale on Budget eve, was kept in the dark about what turned out to be daylight robbery and had to break off a London visit to immediately return to the helm of a badly shaken, perhaps permanently damaged Council.

Of course, we should have seen it coming, even the manner of its execution. A mere dip into the Brandis file reveals ample motivation and similar heists in 2014, if on a much smaller scale, with secrecy their trademark. More on the Brandis mind later.

The loot

The money will considerably add to the extra $6m stash in Brandis’ Ministry for the Arts already nicked from Council, presumably at book-loving Prime Minister Abbott’s behest and committed to a yet-to-be explained The Book Council of Australia. Further funds were lifted from the Australia Council vault in the shape of the Major Festivals Initiative (nicely doubled to $1.5m) and Visions of Australia.

There’s more loot, if not for Brandis but certainly for the Government, in savings via a $28.2 million funding cut across four years and a $4.5m efficiency dividend owed to it from funds granted to the Council. The budget also removes $5.2 million in funding from the Australia Council, and gives it to Creative Partnerships Australia to foster private sector support for the arts.

Senator Brandis deludedly thinks that now there’s more money overall for the arts, claiming on budget night, “As a result of this program, more Australian arts practitioners and organisations will be able to pursue their creative endeavours.” But there’s no new money, only the same loot newly divvied up.

The sheer ease of the Brandis heist has been underwritten by the absence of any requirement that the money grab be properly tested in parliament; the millions have simply been taken from one place to another for spending at the minister’s own discretion—he denies that, but, it’s not at all convincing given his ‘previous'.

It’s the victim’s fault

Lightly grilled by Books and Arts’ Michael Cathcart on Radio National [19 May], Brandis kept his composure—terse, haughty and humourless as ever. The Australia Council’s crimes? “Having its favourites,” being widely perceived as “a closed shop” and as monopolising arts funding. Cathcart asked if having another funding body would make funding more competitive. Brandis thought so: “I can’t see for the life of me, in circumstances where there has been no reduction in the amount of money available, what is wrong with there being contestability so there are two funding streams.” It’s a novel advance on neoliberal principles, a ministry competing with itself as if in a free market, nurturing opportunities for duplication, double dipping, the clash of policies and aesthetics and the building of new bureaucratic machinery for the Ministry to manage applications and the millions seized from its own independent statutory funding body.

Small to medium arts: bystander or target?

If the Australia Council is the obvious victim of Brandis’ machinations, the many more who will suffer collateral damage in the revived culture wars are the artists of the small to medium sector. The 28 major arts companies, 65% of Council’s budget, are insulated from cuts; some of the majors, like Circus Oz and the MTC, have publicly stated that the effect on them will be deleterious as young talent goes un-nurtured.

Brandis’ claim that “This is a very good budget for the arts—there have been no significant reductions in arts funding at all” is, of course, nonsense, ignoring actual cuts and the consequences of depleting the Council. Will small to medium sector artists who have to be abandoned by the Council have a fair go at getting a Brandis? Unsuccesful Australia Council applicants can, says Brandis, turn to his program: “The National Programme for Excellence in the Arts is not a court of appeal from the Australia Council, but it is open to applicants who apply to the Australia Council and miss out.” But with any expectation of success?

The Brandis file reveals the Minister’s examplars of excellence and his distrust of individual artists (quite bizarre for a Liberal): “Frankly I’m more interested in funding arts companies that cater to the great audiences that want to see quality drama, or music or dance, than I am in subsidising individual artists responsible only to themselves” (“A voice for the audience not just artists,”The Weekend Australian, 21 June, 2014).

Brandis has also been openly hostile to the peer assessment fundamental (if much weakened over the decades) to the Australia Council’s ethical spending rationale. In 2013 he attempted and failed to have a clause inserted into the Australia Council Act to allow the minister to change funding decisions at his discretion.

Brandis may well dislike the Australia Council’s independence, but it appears that his hostility is mostly aimed at the small to medium arts sector which the council refuses to corrall, as in the case of the 2014 Biennale of Sydney when participating artists campaigned for the removal of the event’s sponsor, Transfield Holdings, holder of Transfield Services which has contracts with the Australian Government to operate the Manus Island and Nauru detention centres. Brandis was furious with the artists’ conscientious objections, their “blackballing” of commercial sponsorship and formally demanded that the Australia Council, as Peter Tregear put it, “develop a policy to deal with (that is, one assumes, threaten the funding of) any Australia Council-funded body that refuses funding offered by corporate sponsors, or terminates a current funding agreement” (“The art of being wrong—Brandis is wrong about the Biennale,”The Conversation, 14 March, 2014).

Clearly Brandis’ morality has no room for individual conscience when it gets in the way of corporate benevolence. How then do we account for this declaration: ‘The arts should never be the captive of the political agenda of the day: the freedom of the artist to develop his or her creativity wherever it may take them must always be protected and defended,” George Brandis ( “The Coalition’s vision for the arts,” ArtsHub, 20 Aug, 2013).

‘Freedom’ is frighteningly flexible in the Brandis scheme of things: his desire to delete Section 18c of the Racial Discrimination Act would allow us the freedom to be bigots in the street as well as in the privacy of our homes—at the expense of our victims’ freedom. Artists must be free of ideological agendas but not economic imperatives.

The wound

Brandis has palpably wounded the Australia Council at a critical moment when its new Creative Australia plan (fulsomely praised by the Minister in another deftly deceptive move, at the Sydney Opera House launch in November last year when he doubtless knew his intentions) is becoming operational. The many who submitted Expressions of Interest in March this year for the six-year grants (replacing the former triennials) and expected to hear outcomes by the end of May received an email from Tony Grybowski last week announcing a delay while Council accommodated the budget. Clearly, knives will be taken to new short lists, the Council forced to kill off some of its “favourites.”

I only took 20%, your honour

As if to make artists feel better and his actions less heinous, Brandis argued that he took only 20% of Australia Council funding for his Ministry. He denied to Michael Cathcart that his action was the first step in deconstructing the Australia Council—with 80% of its funding intact it would still be the major arts funder in the country (surely for a long time now the States and Local Government). (Figures vary wildly in different accounts, running as high as 88% for Australia Council retention of funds, but the cut is still damaging.)

Loot, largesse & memory

If the Minister can’t keep his hands out of the Australia Council till, can he be trusted to fairly distribute his largesse? What happens to the arms-length and peer assessment principles that have long kept the Minister and Ministry at a tolerably safe distance from Australia Council policy-making and funding decisions? Brandis has declared that, as per Touring Australia and Visions Australia grant assessment in the past, he will have advisory panels—but who will appoint them, who make the decisions and be held responsible for them?

Brandis told Cathcart there had never been complaints about the funding results coming from Touring Australia and Visions Australia when they were part of the Ministry for the Arts. Let’s refresh his presumably fading memory—he was in parliament at the time, even briefly Minister for the Arts and Sport before the demise of the Howard Government.

In his 2005 Phillip Parsons Lecture, Theatre Under Howard, David Marr refers to widely publicised incidents in arts funding in the Howard years. Playing Australia refused to fund Ros Horin’s Through the Wire, a production about relationships between detained refugees and their Australian sympathisers: “What appears to have happened at the meeting of Playing Australia [in 2004] was this: despite the show having a very high score on application, the minister's representative persuaded the committee not to recommend it for funding—on the basis that it was not yet a fully fledged production. Other shows were rejected at the same meeting on the same, unexpected ground…In the industry there's little doubt that Canberra was simply not going to back a politically unpalatable show. Through the Wire was rescued by the NSW Ministry for the Arts which funded eight weeks of what was to have been an 18-week tour. Private backers took it to Melbourne.”

Marr continues, “Another new rule was cited by Playing Australia as a reason for not funding a tour of version 1.0's new work about the Iraq War, The Wages of Spin. It had a season at Sydney's Performance Space in May…and the Theatre Board of the Australia Council pledged $90,000 Mobile States funding towards a five-city tour of little venues. It was rejected by Playing Australia for being too capital city focussed.”