Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

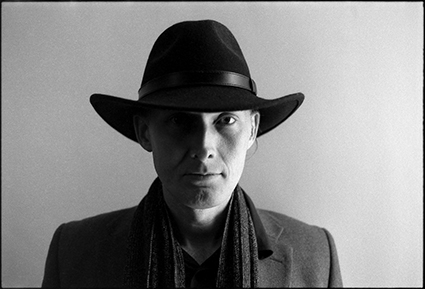

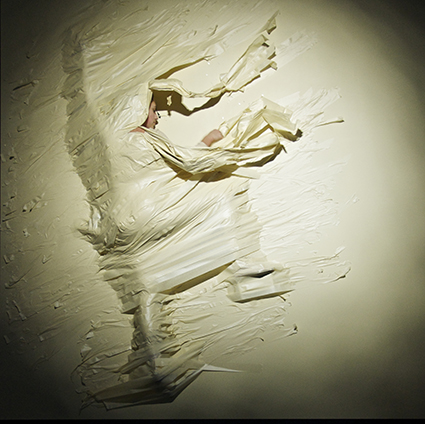

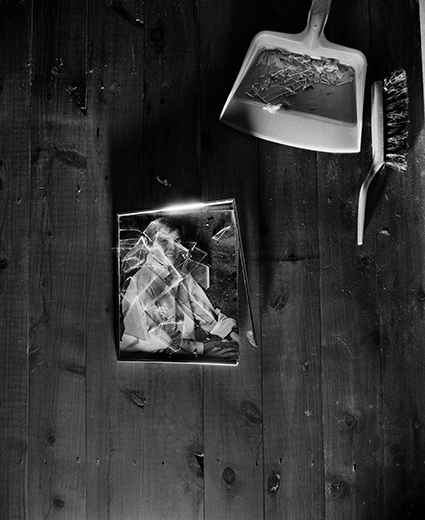

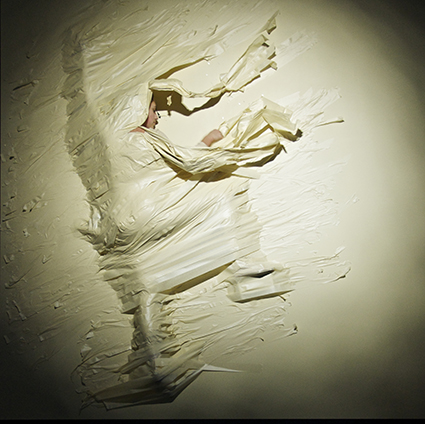

Kialea-Nadine Williams, Trevor Stuart, Madame, Torque Show in association with Vitalstatistix & State Theatre Company of SA

photo Ben McGee

Kialea-Nadine Williams, Trevor Stuart, Madame, Torque Show in association with Vitalstatistix & State Theatre Company of SA

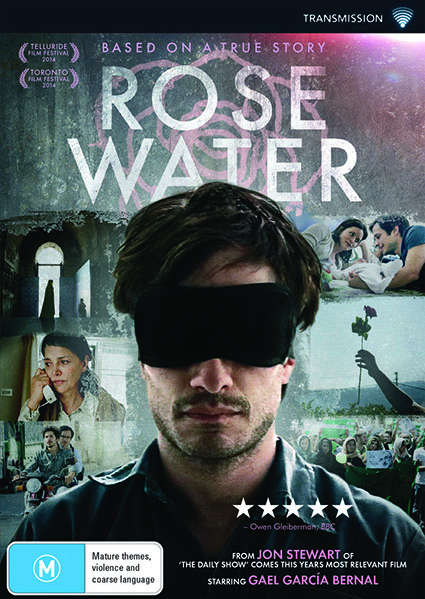

Few visitors to or residents of Adelaide would not profess some passing knowledge of Hindley Street’s Crazy Horse, a fixture of the city’s adult entertainment scene since the venue’s opening in 1979. Its website, perhaps unwittingly, suggests the rapid evolution from chintzy, stage-based variety to the pornified intimacy of tabletop dancing that is one of the strands of a new play, Madame: The Story of Joseph Farrugia, stating “The club combines the lavish cabaret of Parisian strip club ‘The Crazy Horse’ with the full-throttle eroticism of London’s Revue Bar.”

Initially intending to make a show about the strip industry, Torque Show Creative Director Ross Ganf—“fascinated,” according to his program notes, “by the sale of fantasy as a theatrical conceit between a client and a dancer”—became instead drawn to the biography of a single industry figure, Joseph Farrugia, who was installed as Crazy Horse’s choreographer in 1981, and remained its owner until the venue’s sale in March this year. Ganf interviewed Farrugia over a period of four years and the resultant show splices together the conventions of verbatim performance with those of dance-theatre. The work is deepened, not unproblematically, by the incorporation of the shifting vocabularies of strip club performance.

Performers Chris Scherer and Trevor Stuart represent two iterations of Joseph: Scherer the young, somewhat delinquent Nasser regime refugee and schoolboy and Stuart the counter-intuitively sagacious strip club proprietor. Kialea-Nadine Williams embodies Madame Josephine, Farrugia’s commanding and lascivious onstage alter ego. This, however, is rather too simply put—all the identities here are unstable, each subtly framed as emanating from Farrugia’s memory, ego and fluid desires and sense of self. Naturalistic exposition is destabilised by exaggerated gestures and the mouthing of dialogue being spoken by other performers. Scherer and Williams are superb: physically and vocally adept in roles that are demanding in both departments. Stuart’s stage presence is a warm and engaging one, although a certain under-confidence marred his opening night performance.

The show weaves together poignant aspects of Farrugia’s life—his tempestuous relationship with boyfriend Jim, a wounding court case revolving around his relationship with surrogate son Blake—and commendably uneditorialised vignettes that expose the moral grey areas of the strip industry. The most startling of these twins the revelation that a simulated rape scene was performed at Crazy Horse in the 1980s with an unsettling monologue by Williams that draws attention to the aggression and predation faced by, especially, gay and female adult entertainers.

The Burnside Ballroom, with its well-preserved 1950s aesthetic, makes for an appropriately stylish canvas for Geoff Cobham’s showbiz-inflected design, gold foil strips hanging from the ceiling, projections of photographs and sequined curtains, haloed by dressing room lights, shimmering amid cabaret-style seating. The work culminates, perhaps inevitably, in the three performers lip-synching to “My Way,” that ineffably camp, strangely peerless anthem of uncorrupted individualism. “And now,” the song goes, “as tears subside, I find it all so amusing.” As I look back I see the real Joseph Farrugia in the audience. He’s smiling.

Torque Show, Vitalstatistix and State Theatre Company of SA, Madame, creator-directors Ross Ganf, Ingrid Weisfelt, Vincent Crowley, text Joshua Tyler, Ross Ganf, Roslyn Oades, dramaturgy Joshua Tyler, set and lighting Geoff Cobham, sound Luke Smiles/motion laboratories; Burnside Ballroom, Adelaide, 21 April–2 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 42

© Ben Brooker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jack’s Shed, Acoustic Life of Sheds, Tasmanian International Arts Festival

photo Lisa Garland

Jack’s Shed, Acoustic Life of Sheds, Tasmanian International Arts Festival

Circling the milling crowd on a far flung Tasmanian farm is a series of hand built electronic harps amplifying the sound of wind on the strings and creating an intriguing late-afternoon atmosphere. As we are let into the somewhat prosaic tin shed we’re greeted by an unexpected wall of smoke. Three formally dressed players emerge from it on the raised shearing floor and the composition begins with the breathy, loose sounds of Phil Slater on trumpet accompanied by unearthly contrabass recorder played by Genevieve Lacey, its low, fluttering emanation sitting somewhere between whale song and the growl of a beast. Gradually, harpist Marshall McGuire joins the mix. We are participating in Acoustic Life of Sheds.

Part of the Tasmanian International Arts Festival, the production involves established and emerging composers, improvisers, instrumentalists and visual artists working in five sheds across the North West Coast of Tasmania, between Wynyard and Stanley. The project had a long lead-in, with commissioned artists building a visual and harmonic familiarity with selected sites throughout the year prior. In each case, there is a sense that the spirit of the shed, its key protagonists, or the nature of sheds per se, has crept into the work.

We start our journey at a quirky shed on the coast east of Wynyard. Comprising a built collage of ex-prison block and a series of workers huts, this is Bruce’s Shed. The amateur museologist brought these buildings together in order to display his curious collection of items reflecting local history, zoology and his own life. For his live, sonic installation composer Damien Barbeler’s inspiration has sprung from Bruce’s childlike sense of adventure and curiosity, placing players and digital mixing equipment like exhibits within side rooms, while we stand clustered within the central, stone-flagged corridor. Initially in darkness, we are sporadically lit via a ceiling of white balloons that conceal a lighting system linked to the work’s ebbs and flows. The composition uses the instruments to make sampled textural sounds, originating from plucking or scraping on strings, layered against longer bowed notes. “It doesn’t sound like music,” says a young audience member.

The third shed is part of a tiny village of buildings spanning the Table Cape road. Here we meet Jack Archer via his recorded voice, his sheepdog whistles, his sheds, his objects. He is also present as a portrait, taken by local artist Lisa Garland; printed onto thin fabric it ripples in the breeze as Jack ‘overlooks’ performers Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey. The pair, using sampled and live sounds from a ruined piano and a flugelhorn are literally playing in this mechanics shed. They work their way through a series of short pieces that take their lead from Jack’s reputation as a sheep dog trainer. They tinker with sound, mess with the piano’s tuning and speak casually to the audience of their process.

The day-long experience concludes with a three-piece ensemble led by renowned recorder player Genevieve Lacey. She asked the family of Blackridge Farm to keep handheld sound recorders with them over a number of weeks so she could use the recordings to imbibe the life of the farm from a distance: “we eavesdropped on feed runs, overheard quiet, meandering chats and shared jokes, gates and tractors, shearing sessions, pigs being born, birds by the creek”.

The work is in two parts, the first, outside, is provided by an Aeolian harp-fence. The second, by Lacey, for trumpet and harp, brings the shed into the work by wiring it with surface exciters such that every vibration becomes a sound layer. The composition is a contemplative, atmospheric improvisation on the sound diary, full of long, wavering notes that feel in equal part of this place and out of place. Tiny local noises find their way into the work, such as a bird that Lacey memorably mimics with her tiny sopranino recorder.

Acoustic Life of Sheds was a compelling and enjoyable journey of discovery within spaces that usually remain the domain of their owners. The calibre of performers cast for each site made for unique experiences that ranged from the congruent, such as Lucky Oceans improvising country riffs on pedal steel in the filtered light of a shearing shed, to the incongruent—Lacey losing herself in a contrabass recorder. The most successful moments were those where the performers really engaged with the ad hoc spirit of tinkering and ingenuity that is inextricably linked to the Australian shed.

Weeks after the performances and country driving, I still find myself wondering about sheds I pass—what artefacts sit exposed, what they sound like, what the quality of light is from inside the smeary glass?

Tasmanian International Festival of Arts, Big hART Inc; Big hART, Creative Director Scott Rankin, Creative Producer Andrew Viney; Tasmania, 21, 22, 28, 29 March

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 28

© Judith Abell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

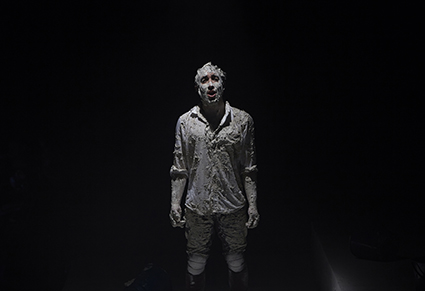

This Fleeting World, Centre for Australasian Theatre

photo Rosie Browning

This Fleeting World, Centre for Australasian Theatre

Living in the deep north of Queensland there’s a heightened feeling of transience, of nature, weather and people constantly on the move. It’s a microcosm of the larger urban demographic but with a sense of community amplified by cultural tourism, which accounts for 80% of the economic equation and the influx of millions of travellers into the region. The uninitiated pursue experience and adventure, while the boomerang of return visitors and peoples to home and country interchanges with life-stylers seeking sea/tree change and migrants hoping for a better way.

Like an estuary tide, this human motion underpins the core of the Centre for Australasian Theatre’s This Fleeting World. The work questions what it means to sense, to feel, to grapple, to be flesh of this earth, if only for a moment. Intertwining an episodic journey with intercultural physical theatre and existential vignettes, the work harnesses a raft of creatives to undertake immersive meditations on the pilgrimage of shared human existence in a transient world.

On entering the work I receive a glossy A4 program revealing a delightful map of “this fleeting world showing the journey” accompanied by a legend of 15 scenes depicting a melting pot of pilgrims undertaking “a journey for their soul rather than their identity.” Piano and percussion are oriented to the right side of the audience who are seated facing the seven performers. The work unfolds over 80 minutes as the performers traverse three basic human behaviours—attraction, repulsion and indifference via the legend’s “home…fields…summit”—on a visceral quest to reach a plateau of mutual acceptance.

This Fleeting World is inspired by the discovery by director Willem Brugman of a prayer hidden in a small, rice paper Buddhist Heart Sutra booklet. With dramaturg Catherine Hassall, the director and performers have composed a poetic treatment for the work using Asian-inclined somatic performance training techniques. The resulting “transmogrifications of being” channel an expressionistic stream of consciousness that would rival Linda Blair’s performance in the 70s film The Exorcist.

The work doesn’t suffer the blank faces of some contemporary dance, nor is it a work of sparse minimalism. The large-scale projected paintings of country by Mavis Ngallametta from Aurukun and potted cultural interjections from the players interact with Linda Jackson’s fluid indigo costumes, to provide an undulating hippie gothic vibe, that won some converts. As one of the audience commented, “not your average primate.”

Built through a two-year development, This Fleeting World had a work-in-progress showing last year, and while the ensemble is relatively new, it’s encouraging to see members maturing and increasingly coming to terms with the movement/text relationship and poetics that populate the work. Much of each performer’s background is invested in the work, the diversity lending itself to the cause and highlighting cultural complexities—those moments where people fumble to communicate, where things are lost in translation, teetering on the edge of misinterpretation, misrecognition and quasi comprehension. The clarity of movement of Eko Supriyanto from Java and Aboriginal Australian Warren Clements contrasted with the rambling utterances and gesticulating of a crouching cluster of performers questing to understand, acknowledge and empathise.

While strengths and weaknesses were evident, This Fleeting World pinpoints the skill, interpretive ability and cultural contribution of each collaborator. The mix of artists—indigenous, non-indigenous and culturally diverse—is reminiscent of the ethos that our community is our theatre company.

Centre for Australasian Theatre, This Fleeting World, director Willem Brugman, dramaturg Catherine Hassall, costumes Linda Jackson, set design Guy & Gina Allain, painting Mavis Ngallametta, ensemble Warren Clements, James Daley, Piers Freeman, Zelda Grimshaw, Catherine Hassall, Dobi Kidu, Miyako Masaki, Lou van Rikxoort, Nasser Selimi, Eko Supriyanto; Centre of Contemporary Arts Cairns, 16-25 April

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 33

© Rebecca Youdell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

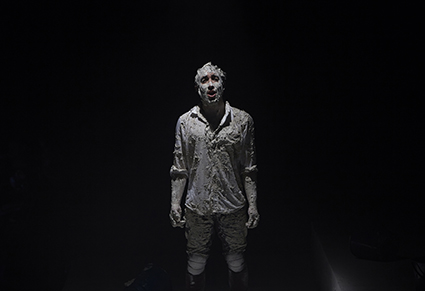

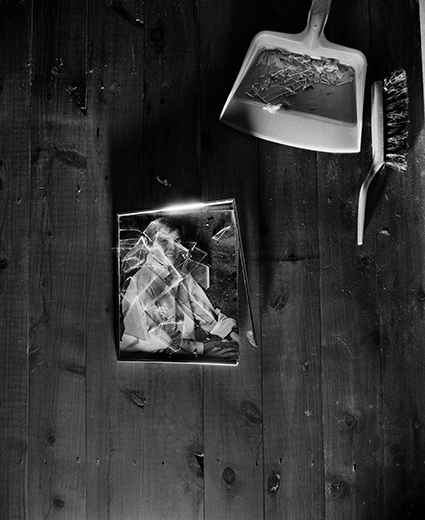

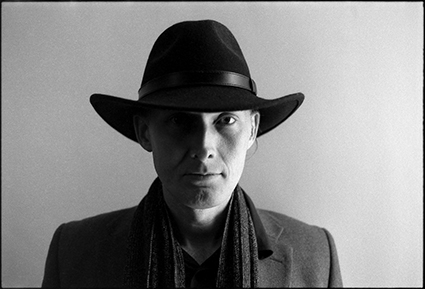

Alan Schacher, Behemoth*, Cementa 15

photo Wei Zen Ho

Alan Schacher, Behemoth*, Cementa 15

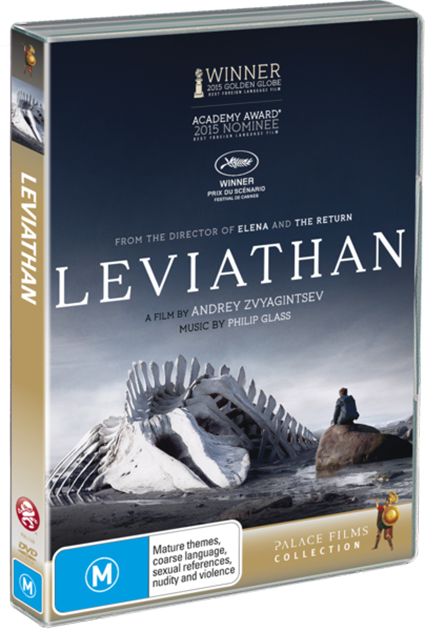

Cementa is part of an expanding ecology of Australian arts festivals situated in and responding to regional living. Based in Kandos in the picturesque landscape of mid-western NSW, the program of the biennale festival’s sophomore year was largely driven by situating artists in the post-industrial town for short residencies and presenting their finished works over a four-day public event.

The Support

Alex Wisser’s The Support was a daily performance in which, acting as a human plinth, the festival co-director stood holding works made by Cementa artists. In one performance he held a styrofoam box, one of a number that constituted Fiona Davies’ installation Blood on silk, price taker price maker. Before him was a wall of identical boxes which, it was suggested, contained human blood and plasma and emitted a frantic audio recording of an auction. For an hour, eyes fixed directly before him and stoic as possible, arms outstretched, box in the palms of his hands, Wisser appeared to embody the struggle that the individual faces to effect change in a capitalist economy. He was not performing a perfunctory or ornamental task subordinate to the work, but actively sharing in it. The daily performances also gently reminded us of Wisser’s provision of curatorial and directorial support.

Alex Wisser, The Support

photo courtesy Cementa 2015

Alex Wisser, The Support

The Ministry for the Future of Art

Artist Nola Farman took similar interest in repositioning what is typically supplementary to the visual art experience, the wall caption or plaque that identifies a work of art in a gallery. Farman’s The Ministry for the Future of Art exhibited a new art movement, “neo-sisyphisianism (neo-potentialism),” curated by Chief Minister Dr Permangelo E. Regularis. We are told the curator cannot be present in person because he is on an overseas sojourn with colleague Fernando Pessoa (Portugal, 1888-1935), inventor of the literary concept of the ‘heteronym,’ an imaginary character created for different stylistic outputs. Indeed all the artists featured are Farman heteronyms through whom she operates individual identities, histories and practices. Her plaques, with their biographies and project descriptions, are displayed in a Kandos garage as art objects in their own right. They lack the subtlety of a convincing ruse, but nevertheless create enticing narrative speculations in which rather ridiculous works are realised in the readers’ imagination. Farman is looking to sell these pieces on the art market (through Dr Regularis), hoping to repudiate the commodification of artists and artworks. Perhaps more interesting is the overt attempt to sell works that only take shape in subjective speculation.

The configuration of yesterday

Filming a volunteer she met at the Kandos Museum and dividing the 40-second film, at twenty-five frames per second, into 1,000 images on numbered postcards, Leahlani Johnson disrupted the people of Kandos’ sense of a linear history. Functional objects, postcards of a moment of movement, suggest much as they are isolated in further moments, dispersed and picked up at numerous points around Kandos and poignantly journeying beyond their place of origin. The postcards’ travelling reflects the individuals who carry them, in the way that history is always carried with us, despite how fragmented and removed it might feel.

The sense of the filmed movement of ‘Helen,’ the volunteer coming into shot and sitting at the entrance of Kandos Museum to knit while waiting for visitors to arrive, is no longer detectable now that the postcards have been dispersed. But this example of everyday history will linger in the distance, fragmented and swirling around town as it continues to travel with visitors and locals.

Childsplay

A bolder confrontation with Kandos’ history took the form of a hopscotch game on squares spray-painted by artist Blak Douglas on strips of pavement in public spaces throughout the town, including the Aboriginal Community Centre. Each colourful arrangement alluded to the Indigenous history of Kandos, including place names and references to massacres. Colours and a readymade play-form enticed an engagement with the hidden history of place, in Kandos and in Australia more generally. Playing became a negotiation with history by inspiring children and adults alike to question their knowledge or ignorance of the information evident in each hopscotch square—both on and about the land it was on.

Cementa 2015

photo courtesy Cementa

Cementa 2015

The District

The District by Karen Therese and Province took the form of a public conversation over tea and biscuits in the Kandos Community Centre. Rather than attempting to represent the community, The District simply created an ever-so-lightly formalised space for locals to enter into public dialogue on their own terms about what interested and mattered to them. This was done through an ever-so-subtle artistic framework implemented but not imposed by Therese. Over the course of an hour people came and went as they wished, narratives and issues unfolding with an organic charm around all facets of regional living, with a candid openness that oscillated between being gently confronting and lightly humorous. Therese’s role as artist dissolved as she simply drank tea with the locals (although at times necessarily promoting herself to leader of this democracy to keep it engaging), while a second-tier of audience sat listening. With simply articulated rules (closely resembling UK-based artist-academic Lois Weaver’s Long Table project), circulated on pieces of paper, the machinery of The District was evident. Anyone could join the table at any time and ask a question of those present. It gave the work a sense of autonomy that had levels of interest for both the local community and the large number of Cementa visitors. As per the rules, there was no conclusion; the conversation dissolved into Cementa and Kandos, prompting continued reflection on life in towns throughout regional Australia where, as one person at The District expressed it, you could enjoy living for 50 years and still not feel like a local.

While I felt that this year’s festival might have benefited from a more concentrated program, Cementa clearly has a bright and exciting future. The most successful of this year’s contributions from more than 50 artists demonstrated an emergent theme, a conceptualising of histories—of artistic conventions as well as Kandos and its people.

*Image caption: Behemoth. performer Alan Schacher as “an Eliotesque figure wandering Kandos. Chipwrapped, coat-stuffed, shredded, balled and plastered. Newsprint in objects, clothing, walls and floors. A relic itinerant inhabitant with many hiding places in the fabric of this town. An Emperor of reveries, a forgotten archive, trailing an elegant debris of irrelevant articles” (Cementa15 catalogue)

Cementa15, April 9-12, Kandos, NSW

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 29

© Malcolm Whittaker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Uncle Vanya, actors and audience, Watford House

photo Tess Hutson

Uncle Vanya, actors and audience, Watford House

I always respond to a house that has a lot to say—and a house that speaks three languages is particularly alluring. On the weekend of March 21-22, Watford House in Avoca in rural Victoria spoke to a small La Mama audience for a groundbreaking version of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. The play’s four acts spanned two days, with various group and private events in between—eating, walking, visiting the Chinese Gardens and processing the intense and unexpected emotions the play evoked in this setting.

This extraordinary production culminated a two-year process, working with the location of Watford House—a wooden house, pre-fabricated in Sweden in 1850 and imported to gold-rush Victoria—that has over the past 10 years been the site of artist Lyndal Jones’ remarkable environmental art site, The Avoca Project (TAP) which hosted the production. During the weekend, the 40-member audience (that’s all that could fit in the house) listened and rejoined as Watford House’s Swedish speaking walls entered a conversation with an English version of Chekhov’s Russian, improvised into vernacular Australian by director Bagryana Popov, the artistic team, and of course the actors on the day.

That weekend in Avoca the fourth wall of traditional theatre resoundingly broke down as the audience perched amid the action, inside and out. Yes, action—I know, Chekhov fans don’t expect action, anticipating instead much talk and a great deal of ennui. But that weekend we were actively on the move: shepherded by the director between rooms, and around outside spaces, then, between acts, making our own way through the Pyrenees. And, yes, there are Pyrenees in Victoria, beautiful, if very dry these days, speaking of the climate change that the characters discuss in the play. Because not only was the text Australian but so too was the context as Uncle Vanya and Sonia became regional Australian farmers, struggling as they do, and the Doctor emerged as an environmentalist, mapping the bush and forests, trying to save what he could.

Uncle Vanya, Watford House, Avoca

photo Stuart Liddell

Uncle Vanya, Watford House, Avoca

The Australian context also informed the production’s intriguing play with authenticity conjured by the timing of each act following Chekhov’s actual timetable. But this was not some straightforward authenticity, as we came to sense with every syllable that emerged from the actors’ mouths and every reference to Australian forests. Uncle Vanya was in Avoca and Avoca was in Uncle Vanya, disturbing any sense that we were experiencing an ‘historical’ play. Also thrown into confusion were audience and actor roles. Not only did we move and sit among them, but for 15 minutes after each act we were invited to stay in our character, as audience, and they as characters in the play. This was charming, if disconcerting at first, but during and after Act 3, all hell broke loose. That Act, the dramatic climax, had the usual fighting, betrayals and recriminations ‘on stage’ and shooting and shouting ‘off stage.’ There were gasps from some of the audience, tears from others—and I admit both from me. So when I encountered the culprit, the Professor (Uncle Vanya fans will remember it was his presence that set everything off and falling apart) in the hallway on my way out, I had a lot to say. What surprised me was how I engaged with him. How could he, I demanded angrily, have acted so abominably, upsetting everyone, concerned only with his own selfish desires? Yes, I actually said this to the Professor, who, true to his character, spat back coldly that he was only thinking of his daughter, then turning away, slammed a door in my face—putting an end to our own play-within-a-play. I was shattered and exhilarated—this was definitely a first for me in play-going experiences.

At every turn, Uncle Vanya in Avoca offered another surprise. As in a Jean Luc Godard film, the unfolding process was made visible and audible and palpable. Particularly striking was the way that, with deft hand and voice the presence of director Bagryana Popov wove through every scene, as she responded to the actors with smiles, nods, furrowed brow and at times even some gentle prodding. Her energy and commitment inflected and infected the event. In the first few minutes of Act 1 when Popov went up to an actor and whispered in her ear, a frisson went through the audience—what was happening here? We knew suddenly that audience, actor, director—not to mention Anton Chekhov—were up for a phenomenal rethink, remix and re-experience and so they were, as this unique and innovative two-day theatre experience unfolded.

–

La Mama, Uncle Vanya in Avoca, director Bagryana Popov, performers James Wardlaw, Natascha Flowers, Todd MacDonald, Liz Jones, Olena Fedorova, John Bolton, Majid Shoko, Meredith Rogers, dramaturg Maryanne Lynch, music Elissa Goodrich; The Avoca Project, Watford House, Avoca, 21-22 March

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 30

© Norie Neumark; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stompin’, 6000 to 1

photo Jasper De Seymour

Stompin’, 6000 to 1

A dancer lies on the floor surrounded by a mandala of ordinary, yet luminously coloured objects from the life of a young person—tennis rackets, DVD sleeves. A female voiceover describes the aftermath of a suicide attempt, a moment when, against all odds, the body rejected a fatal cocktail of drugs. Her voice is followed by another, describing the accidental death of her brother, his organs donated. The prone dancer weeps openly as the remaining performers gently withdraw each mandala piece, stacking the bright fragments in small piles. This is 6000 to 1, a poignant and potent work by Stompin about choice and chance for young people. Drawn from local suicide statistics, the title, and the content, is close to the hearts of its dancers who are aged between 14 and 29.

Chance also plays the audience. Gathering in a carpark adjacent to the venue, our tickets are playing cards. Those with red suits go in one direction, we, with the black, go another. We are told we will need to keep our card with us, that we will be asked to make choices. Throughout the work, staged within an appropriated gallery, the two audiences separate and merge, all of us standing in close proximity to the dancers for each scene.

Each audience is introduced to two stories and a series of narrative fragments, illustrated through movement and voice: “this is not my personal story, but it comes from us.” In one, a girl steps into a pact with death, taking a mix of drugs and drink to end her life. In the other, a sister tells of a brother, horribly injured in a car accident. At the culmination of this first chapter, the two audiences merge and the dance builds in intensity. Initial movements based on joining, separating and re-forming between dancing pairs give way to faster bodily expressions of indecision, fear, tentative reaching, pushing and pulling, forward and back. Again, the dancers’ voices expose us to story fragments: “I was launching myself into the unknown and it was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.” At the narrative peak, movement is frantic, through and around a large, mobile prop wall, its illuminated patterning mimicking our playing cards.

At this point we are asked, as an audience to choose. While we have been asked to show our cards prior within preceding chapters in order to interact (passively) with the dancers, strangely the playing cards do not figure in this last, more consequential choice. I go forward, rather than back. After a penultimate chapter within a darkened, enclosed room, where dancers voice views on fate and faith against repeated gestures and circular movement, we enter the last space and the emotional mandala scene plays out. A live video link connects the split audiences to aspects of the scene they are missing. I find that i have chosen to go forwards in time, toward the culmination of the story.

A Q&A session with the company is the work’s postscript. While this is a debatable move that definitely diffuses the drama of final scenes, it is here that we learn that the narratives we’ve witnessed are true. We understand the way particular gestures formed around stories and why it is that a dancer would weep. While some of the nuances of this difficult subject area have been lost in the translation to performance, the work is undeniably affecting. The minimal yet intimate setting places the audience within the work, the split viewing format underscores the concept of chance and each scene is infused with the personal investment of the performers.

Tasmanian International Arts Festival: Stompin, director, choreographer Emma Porteus, dramaturg, multimedia artist Martyn Coutts, lighting Ben Cisterne, guest choreographer Adam Wheeler, space design Matt Delbridge, costumes Sonja Hindrum, sound arrangement Randall Foxx; Sawtooth ARI, Launceston, 25-29 March

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 32

© Judith Abell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jennifer Lacey, Gattica

photo Ian Douglas

Jennifer Lacey, Gattica

With only passing reference to the 1997 sci-fi movie Gattaca (director Andrew Nicol), Paris-based US choreographer-performer Jennifer Lacey puts the future, the present and the notion of ‘performance’ up for (literal) discussion in her work Gattica (a different spelling). In a piece both funny and philosophical, Lacey playfully jumps from text to dance to dialogue to group invocation, marking the minutes with the friendly rrring of a kitchen timer.

In the beginning: cross-legged on a raised stage, Lacey lights candles, then expounds on ‘the future’ in a tone equally evocative of pop gurus, sing-song TED-talkers and comforting automatons. “In the future we will all wear Prada.” “Dance will remain a minor form.” “Smokers will be replaced on the streets with sugar eaters.” “Art institutions will hibernate and cultural changes will slip in unobserved.” The pronouncements go on for some time as she waves a fan at a pace that matches the shifting urgency or ease of her tone. An ever-lengthening string of scenarios, depressing, silly or hopeful, are spelled out. The timer goes off.

What’s unfolding, though we don’t know it yet, concerns “The Future of Performance.” Lacey’s program note explains that Gattica was made in response to an invitation to address this topic in a forum, and propelled by her feeling that “the future is something I know nothing about and performance is a really broad topic.” In the present, though, things are slightly confusing, as she slips off the stage to the open floor and begins to dance, spike-heeled boots clacking on the timbers. Her body begins a slow improvisation, first marionette-like, knees knocking slackly together. Then, eyes closed, animal, prancing, undulating. Movements that look ‘like’ but are not, familiar gestures. After a while she finds a strong hook in the wall. She tries to climb it using the skirting board, whatever she can, to grip. The timer goes off.

We’ve begun with the future. We’ve seen a performance. Now for the future of performance. Lacey introduces academic and dance writer Philipa Rothfield. A large, low table is brought in on which Rothfield and Lacey both perch. Lacey sets the timer. Bottles of wine are pulled from a drawer. They drink, they talk—about the future of performance. It’s speculative, it’s intellectual, a staged conversation. Genuine, but perhaps not genuine, complicated by the performance space, by self-referential humour, by the containment of time, place and audience. This, for me, is the core of Gattica, interrogating what ‘performance’ is, what ‘the future’ means, unpacking itself, toying with us, submitting to its own unknowns, unfolding in multiple layers. A discussion disrupted by humour; a performance disrupted by discussion; both spontaneous and considered. It keeps morphing between sincerity and staginess. Ideas fly around: anxiety…solicited states of being…crystallisation…anthropology…The borders are erased between the artificial and the natural, between life and representation, between the serious and the frivolous. The timer trills, but they decide to ignore it.

Sometimes performance is defined by the pleasure of the artform itself: my companion, for example, felt she wanted more dance. For me, ‘performance’ is what happens when you give it the name ‘performance’—and then manage to pull it off. A self-fulfilling prophesy, if you’re lucky. Gattica left me thinking: all performance performs the future, bringing the future into being with every gesture. If everything were stationary, what would time be—or past, or present, or future? Without movement, would time even exist?

Final scene: procrastination. Lacey, alone again, wonders whether procrastination means you know intuitively that the thing you’re not doing would be better in the future. She asks us to join her in a kind of ‘spell,’ to bring something from the future to the present. She teaches us a sung refrain of a few words, and conducts us. The words run round in a gentle circle, “I have three horses, I have…three horses, I have…three horses…” We are placed in relationship both to each other and to what hasn’t happened yet, through a ritual with no accessible logic—but a ritual nonetheless.

Jennifer Lacey has described her work as process-based—relying on aesthetic rules, particular body vocabularies and behaviours—but giving priority, ultimately, to the poetic over the conceptual. Her work’s most consistent quality, she’s said, is a “coaxing strangeness.” Indeed, Gattica is strange but lends itself to reflection after the fact. It is amusing, bemusing, bright, funny and at times seemingly random, yet coherent. Performance happens when something is presented, yes? Made present. Hence, ‘presentation.’ The future, brought to the present. Thinking, thinking—and, at the same time, feeling the questions in their lightness, above all.

Jennifer Lacey, Gattica, Dancehouse, Melbourne, 11-12 April

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 34

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Raghav Handa, Tukre, FORM Dance Projects

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Raghav Handa, Tukre, FORM Dance Projects

A softened hum, chant-like, without the intensity or expectation of a chorus to come. Investment in an activity, a small ritual taking place. Low light, ember glow. Small metal objects. Is it a lamp? Somewhat tarnished, I taste rust in my mouth, a quasi-synaesthetic response I have when seeing gold plate in old cathedrals. Rituals confuse the senses.

Rubbed together, these metals make a bearable sound such as industry should make. The rhythm picks up as Australian choreographer and performer of Indian heritage Raghav Handa, with sharpened, precise actions, appears to handle ‘some’ past, while promoting the whiff of a future foretelling: what to expect?

Taking this initial motif, he makes it larger to establish a pattern with slides, criss-crossing forearms, slicing forward and backward—and again. It is a slide between movements’ own Archimedean points: deliberate, aware, no hesitation. The fixed geometry widens after each stroke, opening history and space, waking us from a pinhole presence.

In a big black box, Clytie Smith lights the way with perimeters and planes. There is a sense of growing the movement from the elemental to a larger more complex form. It is extracted from these illuminated hollows and bands, eventually rounding out to explicitly show Handa’s “movement language (of) circular and linear movement patterns.” The relationship could not be clearer.

The sound by Lachlan Bostock is a constant friend to Handa whether sparse or complex in its poly-rhythms and speeds. The tabla sound and rhythm explored through voice and drum, buoyant and crisp upon the flow of strings and electronic instrumentation: movement and music, inextricable.

We are introduced to Handa’s mother Sashi who, seated in a blue dress, looms large over the stage, a spectral figure, sharply projected onto suspended white fabric (filmed by Martin Fox). With a gentle voice, she calls to her son across the seas, the borders and centuries. We come to understand the Indian family tradition and economy of jewellery making, the craft of stone and gem cutting and the melting of metals. The autobiographical places itself on stage as softly as Handa’s floating mother. She tells us of her wedding—heavy with the weight of all that gold.

Handa reminds us (not so gently) that in Australia he is unable to marry his partner (the great shame of this country’s deepened homophobia: a duplicitous celebration of certain stereotypical queer identities while not wholly supporting basic civil rights). We also feel his dislocation from the familial traditions of India, a country that legislates in like manner. Handa, stuck, shuttling between two deprivations in his cultural mobility, without the weight of gold, pairs his hands like two small creatures and plunges them into a ribbon of light bracing the sides of the stage. Fingers rapidly traverse without iconic gesture, from left to right, a ball of symmetrical energy in a fight or frantic mating scene. Handa supports these fingers of fury and fright with a puppeteer’s grace. Graceful he is. Pure even. Spinning and whirling between the tumbling white fabric and, at one time, beneath white robes that whip the air and spin the body like a rip cord, knee traced high into attitude: a balanced display of his signature movement qualities.

The dance is a metallurgical progression: movements extracted and extruded from the elemental, melting and melded, rounded out and sculpted into a family heirloom, subsistence, a way of life, an identity. A work of integrity and pleasure in the moving body that makes one want to move too. We have seen the light, and now I look forward to seeing Handa negotiate less gentle forces with this vocabulary.

FORM Dance Projects, Tukre, concept, choreography, performance Raghav Handa, cultural consultant, performer Sashi Handa, sound design Lachlan Bostock, lighting Clytie Smith, dramaturg Martin Del Amo, film, projections Martin Fox, costume Marissa Yeo, Pheonuh Callan; Riverside Theatres, Parramatta, 29 April-2 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 35

© Jodie McNeilly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sarah Jayne Howard, The Kiss Inside

photo courtesy of Douglas Wright

Sarah Jayne Howard, The Kiss Inside

There is a passage towards the close of Douglas Wright’s The Kiss Inside where Sarah-Jayne Howard, dressed in a mildly antique-cut red dress, executes a measured sequence of movements taken from the work and strung together as a comprehensive digest and delicate meditation on previous material. Arms bared and her muscularity unambiguously on show even as she executes liquid sweeps of the spine before taking her whole frame down to the ground in a more forceful gesture, the section stands out as a rare moment when the diverse components of this work coalesce into something like order.

Wright is one of New Zealand’s most prominent dance makers. After being recruited for his athletic abilities, he moved to performing expressive, narrative solo works whose balletic vocabulary might be compared to that of Ji?í Kylián. Later, Wright moved into various iterations of contemporary dance theatre, drawing on his experience with Australian Dance Theatre and DV8. His work now has more of the disjointed aesthetic of Flemish and German postmodern or postdramatic companies such as Les ballets C de la B. Even so there are moments that echo Meryl Tankard and Pina Bausch in flashes of unadorned, folkloric modernism, as when Wright’s five dancers join hands and execute a simple, dipping line dance as if at a traditional Greek wedding or Purim festival.

The Kiss Inside is Wright’s first full-length work in four years and is mooted to be his last (although this has been suggested before). Promoted as a “kinetic meditation on the search for ecstasy,” the piece also marks more than 10 years of collaboration between Wright and fellow New Zealander Sarah-Jayne Howard (ADT, Force Majeure, Chunky Move, dancenorth).

Like much of Wright’s work of the last decade, Kiss is not a smooth ride. Indeed, it is striking in its choreographic, musical and dramaturgical variety. Scenes cut abruptly into unprecedented new scenarios varying from one in which Craig Bary mimes the act of licking a sharpened knife blade (a rather hackneyed attempt at provocation, apparently drawing on Hindu practice) to the deliberately gratuitous arrival of a figure in a blue gorilla suit, who holds a microphone to prone dancers as they call out “Mummy!”

Several of these images have a rare, Surrealist beauty which arrests attention. In the beginning, Luke Hanna hanging upside-down beside an inverted tree suspended from the gallery, lifts himself up on wide open arms in a V (a gesture Howard invokes in the passage described above) and sings a Waiata, or Maori greeting. Hanna returns at the conclusion, naked, a stack of books bound to his head and a pair of sloping tomes with hard covers tied to his feet, his slow, rhythmic pacing echoing into the darkness as he laboriously crosses the stage.

The movement is equally varied. Accompanied by Klezmer music, Tara Jade Samaya—known to Australian audiences through her work with Chunky Move—performs a complex, fluid set of hand movements which seem inspired in part by classical Indian dance. By contrast, the rough, often ground-based movement of the second scene, paired here with the music of punk goddess Patti Smith, evokes the flinging athleticism of Garry Stewart and DV8. This combination of ambiences makes for a style which never settles into any clear physical or choreographic logic, but rather seems as much of a montage as the radically inconsistent music. For this reason the passage performed by Howard stands out, taking multitudinous, often grating elements and effortlessly blending them.

The Kiss Inside therefore places before the audience in an especially striking manner what one might call the unending crisis of contemporary dance, or alternatively the joyous resolution of this ‘problem.’ Wright does not discard structure, and nor are we fully in the world of the postdramatic, where dance-makers repeatedly stage the collapse of their own dramaturgical conceits. The city I live in, Dunedin, has recently seen a number of such postdramatic works—notably Tassel Me This (Shani Dickins & Jessie McCall) and Footnote’s Bbeals (seewww.theatreview.org.nz).

Even so, Bacchic ecstasy is almost the founding thematic of modern dance via its Ur-text of The Rite of Spring and its countless iterations—including those by Tankard and Bausch. Wright however neither engages with this tradition, nor rejects it by crafting an alternate paradigm. Rather he metaphorically flips the channel, surfs the net and otherwise allows his disparate pseudo-ecstatic vignettes of intravenous drug use, or belief in spiritual rebirth, to fall where they may, producing an effect like scattered leaves. For me at least, this makes for an unsatisfying experience, since the piece neither tells a discernible story (Expressionism) nor causes a new, secret formal logic to emerge out of its materials and interdisciplinary explorations (postmodernism). Between styles and places, The Kiss Inside is definitely Wright’s own work.

Douglas Wright Company, The Kiss Inside, choreography Douglas Wright, performers Douglas Wright, Sarah-Jayne Howard, Craig Bary, Luke Hanna, Simone Lapka, Tara Jade Samaya; Regent Theatre, Dunedin, NZ, 24 April

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 36

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Maggi Phillips, 2009

photo courtesy Anna Phillips

Maggi Phillips, 2009

Maggi Phillips reviewed perceptively, lyrically and idiosyncratically for RealTime for the best part of a decade. She was ever attentive, not easily impressed but fair and never likely to condemn—save in her final review in which she grumpily dismissed Perth Festival works by William Forsythe and Mark Morris while rhapsodising over Aakash Odedra’s Rising. There was a special place in her heart for Indian dance. As editors we’d sometimes return reviews with ‘please explain’ annotations attached to her more poetic responses, which she graciously answered. Occasionally we’d receive a review with a note that said, “This one might be a bit much.” Barely a week before her death we were in touch about reviewing a new show by a young WA choreographer. Maggi and her writing are greatly missed.

Keith and Virginia

We all need a rhinoceros

Famously, somewhere in Perth, there was a photograph of Maggi dancing on top of an elephant. I was never lucky enough to see it myself, but it had taken on the status of legend within West Australia and beyond. It was certainly one of Maggi’s best stories, but it was far from her only one. A significant part of her charm was the way she wove in these tales of her extraordinary career into discussions which, at first glance, might seem to have had little to do with them.

Once when presenting to young honours and postgraduate researchers at the Western Australian Academy for the Performing Arts [WAAPA], Maggi related how she had toured with a company which had a rhinoceros. Whenever she was feeling stressed or wanted a calming break in her routine, she would go to its cage and watch it. She said she found the way it wiggled its ears soothing. We all needed a rhinoceros, she told us her tall, balletic frame curving sympathetically with her deep, throaty laugh.

When I came to WAAPA as a Research Fellow at the close of 2003, Maggi immediately took me under her wing. It was a key moment in my career, being the point at which I flew the world of thesis writing and moved to working at a major tertiary institution. I cannot even begin to count the number of other nervous young scholars and artists she mentored over the course of her life, but all of us felt very loved and protected by Maggi.

Maggi and I often disagreed—but upon the best of all possible terms, of course. Her long, rising exclamation of “owwww!” and the sweep of her arm as she moved her body back away from me in mock anger was a common response. She put on a fine comic show of being shocked at how I referred to Josephine Baker as “Josie,” before she floored me with another of her amazing tales, this time of how a mature Josephine Baker had come across Maggi and her fellow dancers after they had been abandoned by their company manager in South America, when the accounts had gone belly-up. The divine Ms Josephine put on a special benefit show to secure funds to send these poor waifs back home. My own arguments with Maggi—and our many agreements as well—were always based on a shared love of performance in all its forms. I sometimes imagined Maggi as a Josephine figure herself, wrapped in a svelte black knit dress as when she told the story of the rhinoceros. She had both style and charm, and she knew it, but she was always gracious, friendly and loving.

Typically, however, she was modest. She felt she served the arts and students, and did not go out of her way to promote herself, despite the fact that this is what most of us in academia are encouraged to do. She was like her apartment: beautiful but unassuming. I still remember the jars of cuttings growing along the windowsill, a fecund garden sprouting in all directions with the simplest of supports. Back on campus, Maggi agreed with me that the raucous cockatoos which squawked and screeched from the pines outside our offices were, like the rhinoceros, creatures to treasure and revel in—although she did concede she found the way they dropped chewed pine cone fragments on top of her car frustrating. Putting up with a messy vehicle or working on the side-lines was fine with Maggi, so long as there was dance and music in the world.

Maggi’s charisma derived from the manner in which her many life stories and life experiences fed into her day to day life and demeanour. She could move from serious discussion of the latest work by the WA Ballet to relating how as a young dancer, she had stayed at a questionable apartment off a side street in Paris, and how the local prostitutes used to shoo their clients and force them to stand in line, every time Maggi and her colleagues came back from performing in the evening.

Maggi’s degree in world literature and comparative analysis, which she completed after retiring from dancing herself, continued to inform her work throughout her career. She remained sensitive to cultural difference and to the context within which dance and the arts function at all times. She was a tireless advocate of the special forms of knowledge which dance, choreography and the arts offer to society.

One of Maggi’s greatest assets was her openness. Merce Cunningham and Romantic ballet, ballroom dancing and Bharata-Natyam, Maggi loved it all, and while I would often bemoan to her the aesthetics of one piece or another in favour of some purportedly more avant-garde ideal, Maggi was keen to embrace all comers. Although she had a particular fondness for art of the Indian subcontinent, Maggi’s tastes were nothing if not catholic in the truest sense. And we dearly loved her for it. I owe her much, and my thoughts and best wishes go out to all those others who were lucky enough to share time with the woman who taught me that we all need a rhinoceros.

Jonathan Marshall, University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ (WAAPA 2004-08)

Maggi Phillips, 1969, KNIE Circus Switzerland

photo courtesy Anna Phillips

Maggi Phillips, 1969, KNIE Circus Switzerland

Maggi Phillips

Maggi Phillips was Associate Professor and the Coordinator of Research and Creative Practice at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts and led the Australian Learning and Teaching Council project, Dancing between Diversity and Consistency: Refining Assessment in Post Graduate Degrees. In 2010, she received an Australian Dance Award for her Services to Dance Education and in 2013 took on the role of Editor of Brolga—an Australian journal about dance.

Maggi Phillips’ own account of her remarkable pre-WAAPA career can be read on the Tracks’ website www.tracksdance.com.au/maggi-phillips-1944—ballet from the age of six; training at the National Theatre Ballet School; no ballet jobs, so a black and white minstrel show in 1964 (her first professional employment); from 1965 “eight years under Dois Haug (choreographer Moulin Rouge)…with one of her touring troupes [travelling] Europe, Middle East, and South America, in cabaret, theatres, casinos, and circuses;” in Darwin in 1974 as a young mother; 1976 onwards in Darwin variously teaching, choreographing, setting up an amateur dance company, Dance Mob, working with Brown’s Mart on education projects and then as Dance Officer bringing in guest choreographers for major productions, touring extensively to Indigenous communities and establishing the professional dance education company Feats Unlimited, a Brown’s Mart initiative, before relocating to work at WAAPA. Tracks pays tribute to Maggi “as an inspiration and pioneer in bringing modern dance to Darwin,” listing the many people still active in the arts in Darwin who benefitted from her legacy, including current Tracks artistic directors Tim Newth and David McMicken.

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 37

Politely Savage (2005), My Darling Patricia

photo Heidrun Lohr

Politely Savage (2005), My Darling Patricia

It is over 10 years ago now that My Darling Patricia (Clare Britton, Bridget Dolan, Katrina Gill and Halcyon Macleod) boldly dressed the contemporary performance outdoors in what has since become their signature feminist aesthetic. In Dear Pat (2004), three impeccably dressed wartime women plotted out a highly curated sequence of gestural imagining in Bondi’s evening open air, complete with tailored pencil skirt assemblies and tightly crafted pin-curled hair sets. With delicate glances askance and waving from afar, their high-heeled bodies carved out the physical geometries of a nostalgic other-time, long before Mad Men plunged the post-war feminine back into mainstream view.

Dear Pat was the second of the company’s public, site-specific works, building on the character types foregrounded in the domestic spectacle Kissing the Mirror (2003) a year earlier. Positioned in the intimacy of a Petersham caretaker’s apartment, Britton and Macleod physically stuttered as they poured themselves tea, Macleod’s fine porcelain teetering, Britton hunch-backed and drooling. Where Dear Pat built on the ‘chronotope’ of the post-war woman, these aged women instead envisioned her demise, at once imagining into old age and also seeking through her perspective the gendered traces of a former heyday. Both works ascend to the calamity of a salacious reveal: the old women conduct a slow rooftop embrace with alien-foetus-like puppets (their inner selves, their lost ‘twins’?), and the women in Dear Pat are seduced by a large inflatable multi-titted vision of the monstrous feminine herself.

In both works, this distilled staging of a precisely feminine aesthetic is what enables the company’s feminist politics to take shape. Speaking to Macleod and Britton in the aftermath of their company’s 11-year success—My Darling Patricia has recently drawn itself to a close—it becomes clear that these very productive tensions between inner and outer worlds, working across the dynamics of intimacy and spectacle, have grounded their theatrical vision from the beginning. Britton describes how key early influences in physical as well as visual training from PACT, COFA, Performance Space and Erth, as well as mentors such as Chris Ryan, Robert Lepage and Philippe Genty, landed their practice at “a cross-[roads] between performance and sculpture.” It also becomes clear that this desire to articulate what Macleod emphasises as “a visual language [working] through the performance” is inseparable from the thematic terrain the company has continuously evoked.

Their prize-winning work Politely Savage (2005; R67, p32; RT68, p47;), which interestingly seemed to enfold the dynamics of site-specificity into an enclosed theatre space, fleshed out these duplicities by exploring what Britton describes as an ongoing curiosity in “artifice, or that difference between how something looks and what’s going on inside—people who were performing a version of their lives for other people.” Macleod names this the “polite woman as a type…that need to be nice and polite and pretty” and notes how dramaturgically the polite woman can operate as “a gateway to this other thing: the imagined world, the mythic world.” It is the company’s signature ability to summon the mythic that has resulted in their work often being labelled suburban-gothic and I ask them whether their interest in the monstrous feminine might have in addition opened out a more located investment in a particularly Australian form of gendered experience.

Night Garden (2009) My Darling Patricia

photo Heidrun Lohr

Night Garden (2009) My Darling Patricia

For them, the suburban necessarily resonates with inverse ideas of the internal for how it “brings up those notions of a banal veneer and something subterranean and more interesting and grander underneath.” The suburban gendered experience hinted at in the historical flavour of the post-war trilogy is fleshed out further in Night Garden (2009; RT90, p46) which works with a transverse stage to envision the waking dreamscape of a mother caught in what the audience experiences as both a social and spatial frame. The socio-economic landscape in this work is further drawn into stark relief in Africa (2009; RT 94, p40) where we witness the inverse of the mythic feminine to instead see her brutal domestic reality. Puppet children here focus the child’s perspective of an adult world: adults are only ever seen from the waist down. The monstrous feminine, who in earlier works has been visualised as a vagrant puppet-child-creature—the mythic imagining of female repression itself—is here decidedly not metaphorical. There is no poetic relief cast by the otherness of these puppets, but rather a crushing finality to the fact that their very otherness materialises what is culturally cast aside. The puppets here speak to the monstrous landscape of social disadvantage.

While gendered experience is the subtext of much of My Darling Patricia’s work, their operating context is also explicitly feminist in that it “is trying to actively create more female perspectives and work with female collaborators. Not exclusively. We’ve worked with a lot of lovely men as well. But we’ve definitely tried to have an impact that’s empowering of women,” Britton explains. Macleod adds, “Women in the room have always been in control of the process and of the room and of the artistic vision and of the collaborations,” acknowledging as well that the concepts behind Africa and The Piper were from Sam Routledge. In navigating the evolution of their company aesthetics it is interesting that the seeds planted by their early works evolved to craft two very different theatrical worlds in the latter stages of the company’s life. Posts in the Paddock (2011; RT107, p38) and The Piper (2014); both abandon this early interest in the mythic female to respectively contemplate historical and children’s perspectives.

Dear Pat, My Darling Patricia (2004)

photo courtesy the artists

Dear Pat, My Darling Patricia (2004)

As children enter the frame (Macleod is currently nursing her second child and Britton had her son just after Politely Savage closed), I ask whether they’ve experienced gender disadvantage in accessing funding for their works; they mention their proposals to funding bodies about establishing a childcare fund to support interstate collaborations and touring works. As artists, they need childcare that covers intensive periods of work when living away from home. Britton explains the brutal pragmatics of the situation as a compromise between earning less than enough versus nothing at all: “You can either compromise on childcare [budget] or put in an application that’s less competitive because it’s more expensive.” In this context, two of the company’s founding members, (Katrina Gill and Bridget Dolan) were challenged by the demands of interstate collaboration with young children. Dolan is now a practicing painter and Gill is on a similar trajectory. At the same time, Macleod and Britton also acknowledge that these concerns might now be dwarfed by larger threats to any form of experimental practice given the recently proposed cuts to arts funding in Australia. Macleod hence notes the benefits of paving the autonomous path that they’ve set for themselves, where “wanting to create experimental projects and realise your own ideas and not wanting to answer to someone else” is a privilege.

All of this might lead you to think that Britton and Macleod could be in need of a rest, but speaking to them on the cusp of new horizons, these women are already fleshing out their next trajectories. For Macleod an interest in textuality is taking her to a collaborative development in Barbados, and for Britton, an interest in Australia’s broken relationship to its past is currently taking her rowing down the Cooks River. In addition, The Piper will be touring to Edinburgh Fringe Festival in August and they are also looking to remount their most recent work Mantle, which premiered at Campbelltown Arts Centre late last year. Perhaps rather than monstrous, these women have found a ‘feminine’ of a different order: both tenacious and steady, to say the least.

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 38-39

© Bryoni Trezise; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Into the World, David Weber-Krebs

photo courtesy the artist

Into the World, David Weber-Krebs

There is something bittersweet about seeing excellent performance works in Brussels, only to realise that they are made by Australians. There are not too many Australian performance-makers in Brussels, but, due to the dense network of performance venues in this corner of Europe, and the prominence of Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris and London as meccas for theatre lovers and theatre makers, one sees many pass through.

Encounters with the Australian makers are often accidental and serendipitous, and say a lot about the artistic networks criss-crossing Europe. Both shows covered here had only two-day seasons. After we enthusiastically cross-examined the artistic team during the post-show Q&A, one of the performers in Into the Big World, Noha Ramadan, approached us inquiring: “Are you also Aussies?” Ramadan is based in Amsterdam, while David Weber-Krebs (Belgium/Germany), the author of Into the Big World, is based in Brussels but works all over Europe. The author of the second piece, For Your Ears Only, Dianne Weller is a performer, actor and singer who originates from Sydney and arrived in Brussels many years ago via London. I met her through a British friend, who collaborated on this work.

Australian artists in Belgium tend to be light, rested, unburdened by the questions that trouble their peers at home. If they are eligible for domestic funding schemes, like Weller, then they have long-term work security unimaginable to an independent artist in Australia. Local politicians do not attack their profession as a matter of course. And when they make challenging, ambitious works, such as the ones I’ve seen, the audience really pays attention. It should all be so easy.

Dianne Weller, For Your Ears Only

For Your Ears Only is ‘radiophonic theatre’: the stage remains in the dark throughout the performance, with only very discreet changes in lighting, while we listen to three critics (Andrew Haydon, Pieter T’Jonck, Elke Van Campenhout) debate the merits and demerits of the performance we are not seeing. The performance engages in two lines of inquiry: the evocative power of sound, and the possibility of recreating the theatrical experience from documentation. For Your Ears Only builds a vast edifice of interpretation around a show that never existed: the audience sees it through the prism of criticism, the critics have only seen documentation material, and the artists have ‘documented’ a show they never made.

Of course, as Forced Entertainment and similar groups from the 1990s, as well as much contemporary immersive theatre, have proven conclusively, sound is often all it takes to evoke a full experience. Having practically ‘seen’ the show in question, I feel fully authorised to tell you that it features a three-storey house with rooms outfitted to evoke popular films: Eyes Wide Shut, American Psycho and similar, through which actors move, performing short scenes. Through a pair of multimedia goggles and headphones, we can zoom in on separate rooms and hear the dialogue. In Haydon’s words, it feels like “the Internet version of watching theatre.” The rooms do not amount to a logical house: among the more ordinary bathroom, kitchen, corridor are motel rooms and a large ground-floor gallery. The spaces are deeply imbued with cultural significance, moreso than with architectural logic; for Campenhout, the entire house feels like “some kind of sanatorium for the sentimentally displaced.”

For Your Ears Only, Dianne Weller, Apocalypse 2

photo/video Alessan

For Your Ears Only, Dianne Weller, Apocalypse 2

The scenes excavate the deep cultural memories associated with the home, which tend towards images of violence, particularly violence against women—a surprising revelation about our collective imagination, contrary to the common discourse on women’s safety. For Campenhout, a seedy sexuality reminiscent of Brian de Palma films permeates the show, not least because the spectator feels like a voyeur, having to choose which of the rooms and actors to focus on. The world built in the work is deeply paranoid, a world of men reassuring themselves of their strength by using women—all three critics draw convincing comparisons to an urban, peace-time version of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now—and creating larger-than-life cultural hallucinations to replace reality.

Watching/listening to For Your Ears Only had intriguing parallels to calling a phone sex hotline, the (now vastly outdated) version where the listener dials into a pre-recorded audio story: the general seediness of the experience, the thematic intrusion into domestic scenes that fetishise the women who inhabit them, the reliance on the experience of the spoken description of events, as well as the very strange disjunction between feeling like a voyeur and not being able to see. The male gaze structures both, but the absence of visuals allows us to imagine things just right: the show in For Your Ears Only was exactly to my taste.

David Weber-Krebs, Into the Big World

David Weber-Krebs’ Into The Big World is the best performance piece I have seen in years. It concerns itself with nothing less than how European science organises knowledge. It traces various scientific methods, taxonomies and epistemologies through history, progressing from direct observation and unstructured lists to detailed taxonomies and theoretical models, to active meddling into natural processes. This progress is brilliantly embodied on stage by two performers, Noha Ramadan and Katja Dreyer, who chant and list and enumerate the things we know on an empty stage. As the knowledge becomes increasingly abstract, exact and the facts distanced from the quotidian life, so the interaction between their bodies and the set (sculpted economically with lighting and sound) becomes disjointed, distant and rigid. With a rigorous minimalism, the organic liveness of performance becomes an oppressively rigid clockwork, the language shifts from ‘Here is…’ to ‘I know…’, and a sensuous exchange between bodies and the space surrounding them becomes manipulation, then abstract ownership.

The ideas in the piece are masterfully expressed with a sensibility that is unmistakably choreographic: Weber-Krebs sculpts and articulates body, space and emptiness as precisely as a a master craftsman fashions wood into a chair. Moreover, this is not a live artist’s activist critique of abstract reasoning, and in no way a naïve work. Weber-Krebs has created many pieces with and for museums, and Into The Big World is a very informed performance. Its diagnosis of how our entire embodied lives are shaped by the scientific thought is accurate and precise: it equally describes the changes to how we eat, cure illness, how we attempt to harness energy or mitigate climate change. I am in no doubt that an audience of scientists would hugely enjoy Into The Big World.

I am also in no doubt that sound engineers and archivists would love For Your Ears Only: both approach their material with a rigour and conceptual depth that, paradoxically, makes their philosophical inquiry universally accessible, across relevant disciplines. Neither work obfuscates, but enlightens. In a comparatively more stressful, product-oriented and commercially minded ecology of Melbourne, I rarely see this level of rigour achieved by local artists. But it is rarely demanded, either, and this is why the experience of these two works was bittersweet.

For more on David Weber-Krebs see Virginia Baxter, In Between Time Festival, 2006.

For Your Ears Only, Dianne Weller, sound artists Ruben Nachtergaele, Ludo Engels, critics Andrew Haydon, Pieter T’Jonck & Elke Van Campenhout, lighting design Hans Meijer; Julie Pfleiderer, Beursschouwburg, 19-20 Feb; Into The Big World, by David Weber Krebs, performers Katja Dreyer, Noha Ramadan; Kaaistudios, Brussels, 10-11 Feb

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 40

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hoofer Dance, Free the Arts Rally, Southbank Melbourne, May 22

“We will force Senator Brandis to have the public consultation he has avoided so far,” declared Mark Dreyfus, Shadow Minister for the Arts on 2 June. As we go to press, the Federal Opposition is calling for a Senate inquiry into the “Coalition Arts Slush Fund”—the $104.8 million heisted from the Australia Council to fund the new “National Programme for Excellence in the Arts” within Attorney-General and Arts Minister Senator George Brandis’ own department.

In recent weeks Media Arts & Entertainment Alliance petition has been circulating, a national protest held (see editorial), dozens of public statements made, mostly by the now at-risk artists in the small to medium sector but also Artspeak (the confederation of national peak arts organisations), letters of complaint sent to Minister Brandis and many significant articles published, especially online. Rumours abound that the Minister’s department brought pressure to bear on major performing arts organisations not to get involved in the discussion after Queensland Theatre Company artistic director Wesley Enoch, the State Theatre Company of SA, Black Swan and Circus Oz made their concerns public. There’s an understanding among the major companies that their wellbeing relies in the long-term on the health of the small to medium sector, but will they (CAST, the Confederation of Australian State Theatre Companies) come together to protest Brandis’ action?

While there’ll be no support from Opera Australia (“we’ll take money from anywhere,” said the company’s General Manager, Craig Hassall) or the Australian Ballet, it’s important that artists form an otherwise united front against the most significant assault on the Australia Council in its history and, above all, the contempt of this Minister for a large proportion of Australia’s artists. Let’s hope that by the time RealTime is on the streets, a Senate inquiry will have been scheduled and Brandis taken to task. The $104.8 million must be returned.

Read Major art heist: the Brandis file, our analysis of Senator George Brandis' recent budgetary decisions, published in the May 20 Profiler.

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 25-26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

‘Theatre restaurant’ is a descriptor that brings with it a distinct set of connotations, and they’re of the sort that few outside the actual theatre restaurant industry hope to have bestowed upon them. It was with some rare delight that I saw a recent venture by Melbourne polymorphs Aphids consciously billed as “part theatre restaurant.” Of all the denigrated forms that have been reclaimed of late—pantomime, burlesque, variety—this was one I never saw coming.

A Singular Phenomenon, Aphids

photo Bryony Jackson

A Singular Phenomenon, Aphids

Aphids, A Singular Phenomenon

A Singular Phenomenon does indeed have something of the theatre restaurant atmosphere to it, not merely due to the serving of plates of pasta to audiences. It’s the proudly communitarian spirit the work aims towards, a question not so much of the low-brow populism we often associate with the theatre restaurant (or cruise ship, or corporate event) as a no-brow anything-goes approach that seems unaware of the existence of theatrical convention. It takes quite a bit of art to appear so unselfconsciously artless.

The work has at its centre a truly iconic Australian pop song of the 1980s that will be instantly recognisable if you’re over about 30, though it’s almost certain you haven’t thought about it for many, many years. I’m told that Aphids hopes to remount A Singular Phenomenon elsewhere and so I’m wary of revealing the song’s identity, but the piece is certainly stuffed with enough business and detours that foreknowledge would be unlikely to detract from the experience. Still, I’m keeping mum.

I can reveal that the structure of the work sees audience members assigned characters from the history of the song and its creator, and as an extended role call is announced these characters take their place upon the stage. No interaction is required beyond that; we’re merely placeholders and the random allocation of parts is democratic enough.

There are exceptions in the form of real people who loomed large in the song’s history, and who take to the stage as themselves. On opening night the reviewers in attendance were also summoned under their real titles, which initially struck me as juvenile—’outing’ critics while The Blackeyed Peas song “Shut Up” blares from speakers is oddly antagonistic in a work that is otherwise carnival and celebratory. But if we’re to be the representatives of authority in a dynamic that otherwise seeks to level power structures, then so be it.

Charting the biography of a song is an interesting premise, though this history is entirely sympathetic to its subject and there’s not much critical edge to it. The production occasionally strays into murkier territory, such as the spurious claims of child pornography the song’s creator was subjected to after posting images by a well-known international artist to Facebook. But thankfully the behind-the-scenes life of this figure, and the track itself, is full of enough bizarre detail and cultural significance to warrant a mere blow-by-blow recounting, which is finally what A Singular Phenomenon amounts to. To throw too much dialectical critique into the mix would perhaps be to its detriment.

The Living Museum of Erotic Women

The Living Museum of Erotic Women is another event that is wholly celebratory, in this case of a quite astonishing array of women across history. It’s set up as a sprawling installation spanning five storeys and while there’s a vague nod to UK theatre company Punchdrunk Sleep No More (2011) in layout, the similarities don’t extend too far. Performers in various rooms enact vignettes, soliloquies, dance and burlesque routines, and audiences are mostly free to wander between each with the occasional gathering for a special routine in a shared space.

The women performed range from the familiar—Mata Hari, Marlene Dietrich, Salome—to the more esoteric, such as the Mongol warrior Khutulun and Kabuki’s Izumo-no-Okuni. At times the focus on the erotic aspects of these appears outlandish. Joan of Arc seems a weird choice, for instance, but here proves a worthy one in a solo routine that produces uncomfortably sado-masochistic imagery of torture, resistance and ultimate defeat. The ‘She-Wolf’ Messalina is another memorable addition, snarling and prowling a space covered in severed penises, problematising the gaze of viewers by reminding them of their own precarious physicality and proximity.

This is, again, not a particularly critical work. For the most part it’s an unalloyed tribute to the spectacle of femininity, and if the function of spectacle and masquerade isn’t particularly questioned here, at least the variety of modalities through which that femininity can be expressed is encouragingly diverse. There’s also a certain queering of essentialism, with the artifice of representation never confused for the ‘real’. Some of the acts on offer suggest a rich sense of craft and subtle nuance, while others are charming in the simplicity of their intent.

Semaphore, Kate Neal

photo Sarah Walker

Semaphore, Kate Neal

Kate Neal, Semaphore

There’s no doubting the technical skill and rigorous discipline behind Kate Neal’s Semaphore, on the other hand. This is a consummate feat in sound and dance. Inspired by her father’s time spent working as a signalman in World War II, Neal draws on visual and auditory codes such as Semaphore and Morse code and refigures them in extraordinary ways.

Neal is a composer and the work is primarily sonic—a heavy emphasis on percussion sees the employment of dozens of drums, bells and other strikable objects, while even breath itself is choreographed in percussive ways. The sharply regimented syncopation at times slides into ravishing piano glissandi and arpeggiated strings, suggestive of the rolling seas the signalman traversed, while brief sequences of animation and video provide context from Neal’s father himself.

All of this would make for a terribly fine work, so it’s quite an accomplishment that the addition of a potent dance element doesn’t distract or muddle the focus. Timothy Walsh’s choreography bleeds into Neal’s composition as semaphore flags slice the air with audible snaps and flutters, while the musicians are given movements that make their own performances dance-like. The bright red and yellow of the swung flags is made more pronounced by a gentle aura of blue light, and thick haze effects make more solid the air in which these signifiers mingle. If the staccato telegraph and the blinking signal light can be considered their own forms of language, Neal has proven that they’re as capable of poetry as any other.

Aphids, A Singular Phenomenon, creators Lara Thoms with Aaron Orzech, Liz Dunn, original project development by Tristan Meecham, The Merlyn, Malthouse Theatre, 2–23 May; Bernzerk Productions, The Living Museum of Erotic Women, director Willow J Conway, End to End Building, Collingwood, 12 May–7 June; Semaphore, composer, concept: Kate Neal, director Laura Sheedy, choreographer, dancer: Timothy Walsh, animation, video: Sal Cooper, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, 27-31 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 43

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tom Budge, Hugo Weaving in Sydney Theatre Company’s Endgame

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Tom Budge, Hugo Weaving in Sydney Theatre Company’s Endgame