Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Nominate for ONE giveaway. Email us at giveaways [at] realtimearts.net with your name, postal address and phone number. Include ‘Giveaway’ and the name of the item in the subject line.

5 Copies of Citizen Four, the breathtaking documentary about Edward Snowden (courtesy of Madman Entertainment).

5 Copies of Citizen Four, the breathtaking documentary about Edward Snowden (courtesy of Madman Entertainment).

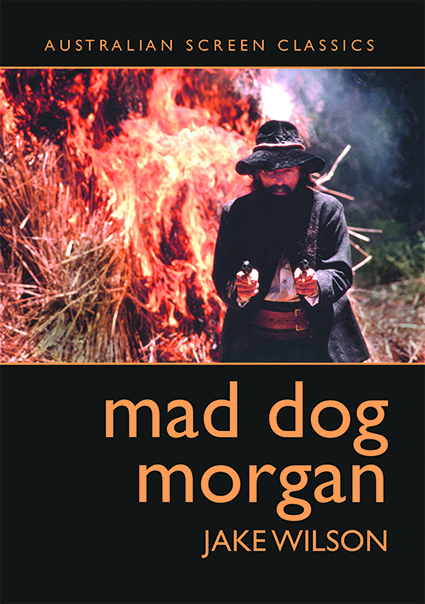

3 copies of Fairfax film reviewer Jake Wilson’s entertaining reassessment of Philippe Mora’s Mad Dog Morgan (courtesy of Currency Press).

3 copies of Fairfax film reviewer Jake Wilson’s entertaining reassessment of Philippe Mora’s Mad Dog Morgan (courtesy of Currency Press).

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 39

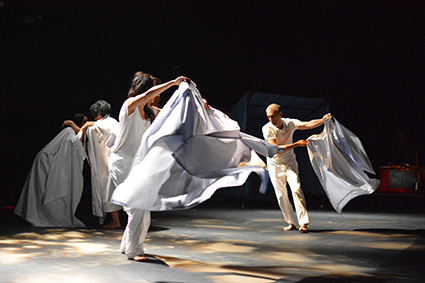

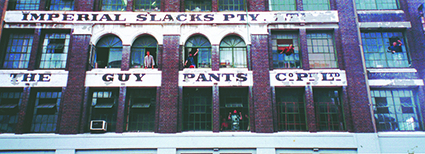

HOME, QTC

photo Bev Jensen

HOME, QTC

In Queensland Theatre Company’s foyer library, we are offered a choice of green or oolong tea and a home-made biscuit before entering Margi Brown Ash’s HOME, which had premiered in La Boite’s Independent season in 2013. This production is the first to use QTC’s intimate new performance space, the refashioned Diane Cilento Studio. The technical direction of Freddy Kromp, the lighting design of Ben Hughes and the visual artistry of Bev Jensen have converted this white box into a hearth, framed by video projections of lace curtains and filled with books, bespoke chairs of various sizes and hanging perspex picture frames adorned with quotes referring to memory, remembrance and the passage of time.

Travis Ash plays a piano score and Brown Ash enters and announces that this is a performance about storytelling—a telling of a version of her life that she will later conclude is underpinned by no assumption of an authentic or ‘real’ self. “I will play my part and dream this potential. I will ask some of you to join me.” She begins with a retelling of her favourite story—a foundational Egyptian myth about Set, Osiris and Isis treating each other appallingly. It is a story, ultimately, about family and betrayal and retribution and love and longing and remembrance. And we are launched into this warm, astounding, deeply idiosyncratic semi-autobiographical and un-pigeonholeable performance piece, swept up in the storytelling as though we are in fact sharing a magic carpet with Scheherazade herself.

The intimate studio space is a perfect home for this theatrical experience, premised as it is on sharing family stories with a complicit audience who are asked to join the performers on stage and substitute for Brown Ash, her mother, her husband and children at various points in their richly matrixed lives. While Brown Ash provides the confessional heart to the piece, composer and son Travis shares interspersing socio-political vignettes that link the family’s personal trajectory to matters of conscience in the outside world—Vietnam War protests, Palestinian resistance, Christmas Island refugee shipwreck survivors. The personal and the political are entwined here. Each of us has our own story and we are all interconnected, the piece seems to be telling us. Every family has its own mythology, and the public exchanging of these intimate revelations constitutes acts of bravery, acts of vulnerability and exposure that remind us how human and eternal we are.

It’s hard to do this entrancing work justice in a short review—the exposure to the way Brown Ash’s brain works (beautifully in tandem with director and long time collaborator Leah Mercer) is a richly rewarding experience. I wanted to share this experience with loved ones—my son, my mother. Margi Brown Ash is something of a state treasure and it is terrific to see experimental, thoughtful, interrogative and elaborately textured work like this sneaking into the QTC ancillary program.

QTC & Force of Circumstance: HOME, writer, performer, devisor Margi Brown Ash, devisor, director Leah Mercer, writer, performer, composer Travis Ash; Diane Cilento Studio, The Greenhouse, Brisbane, 14-25 July

Congratulations to Stephen Carleton on winning the 2015 Griffin Theatre Award for best new play by an Australian playwright, The Turquoise Elephant, an absurdist work depicting the chaos of a future world rapidly succumbing to climate change. Eds

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 41

© Stephen Carleton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

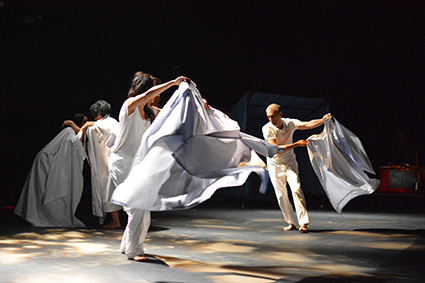

100 Reasons for War, Blue Cow Theatre

photo Tony McKendrick

100 Reasons for War, Blue Cow Theatre

Looking back to late April in Hobart, the summer festivals were over, Dark MOFO lay ahead, yet there was plenty to tempt the cultural connoisseur with a taste for theatre. When I say plenty, I mean three professional shows opening at once, but that’s a big deal here. The amateur theatre scene has dominated for decades, in terms of both the resources it commands and the audiences attracted. Professional theatre, by comparison, has struggled. One of the mainstays has been Terrapin Puppet Theatre, founded in 1981 and still going strong (although the effects of recent Australia Council funding cuts remain to be seen), delivering theatre for family and schools’ audiences. But others have come and gone, with artists segueing into related fields or moving to the mainland in search of that ever-elusive sustainable arts career.

In Launceston Mudlark Theatre has been producing outstanding theatre since the mid 2000s, leading the way in terms of commissioning—including plays by Tasmanian playwrights Carrie McLean, Stephanie Briarwood and Finegan Kruckemeyer. Its activities to foster the independent scene, such as its One Day 24-hour short plays project, are impressive. Their latest is The Possum, written by another local, Sean Monro, which, like many Mudlark shows, engages with the traditions of Tasmanian Gothic.

But what can the three productions in Hobart in April tell us about the character of Tasmanian theatre in 2015? This level of activity is unusual, but with a new company—The Southside Players—coming along with its first show this August, it may be the way of the future.

The Blue Cow Theatre presented 100 Reasons For War, a new play by Tasmanian playwright Tom Holloway, staged in the Theatre Royal with a cast of eight and one of those scripts where lines aren’t allocated to particular characters. Impressively staged by Robert Jarman, it featured the use of a video screen with text to underline story moments, eclectic lighting and intense sound design by Dylan Sheridan. There was an exuberant physicality to the piece, with choreography by Trisha Dunn, including a striking moment with the ensemble on a tilting revolve. Holloway’s script explores Anzac themes in a tangential way, reflecting on violence in the human animal while highlighting ideas around gender. It also references The Black War, a shameful chapter of Tasmanian history, as the conflict that has shaped the Australian national identity far more than the Gallipoli defeat—a provocative idea ripe for further exploration. The response? Audiences either loved or loathed it.

Founded by actor-director Jarman, actor John Xintavelonis and actor-writer Jeff Michel, Blue Cow Theatre launched in 2010 and has staged 10 productions since, with 100 Reasons For War being their third commission. The second appearance of their script development initiative, The Cowshed, in 2015 suggests there will be other original work to come. Whether the next will be in the vein of a Holloway or a Jonathan Biggins (Blue Cow staged his comedy The State of Tasmanian Economy in 2014) is the question.

Tasmanian Theatre Company staged Nassim Soleimanpour’s acclaimed allegory White Rabbit, Red Rabbit. Showcasing a different solo performer each night to preserve its spontaneity, it’s unrehearsed. There’s no director because the actor directs him/herself, or, to be more accurate, the playwright directs through time and space via the sheer power of words on a page (it was written in 2010 as Soleimanpour’s effort to connect with a world outside his restrictive life in Iran). The TTC line-up was diverse, with Hobart-based actors Anne Cordiner, Bryony Geeves, Ryk Goddard, Jane Longhurst, Katie Robertson, Mel King and Guy Hooper as well as Gavin Baskerville, who’s better known as a comedian, and fly-ins Samuel Johnson, Kate Mulvany and Hamish Michael (an expat Tasmanian). I saw it on the night that Jane Longhurst was in the hot seat and it was a powerful experience (although one niggling thought is that for a grassroots activist play it’s a shame that only those with a spare 40 dollars got to experience it).

Tasmanian Theatre Company was founded in 2008 when there hadn’t been a state theatre company for about a decade. It’s taken a while to find an identity for itself, and is perhaps still looking. Having lost state government funding last year, it has a hard road ahead. But it has certainly hit on something, with increasingly innovative approaches to staging, such as a very popular production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf late last year coinciding with Architecture Week. This took place in a 1960s Modernist house designed by Esmond Dorney and owned by the Hobart City Council. Audiences were ferried to the site at the top of Sandy Bay by mini-bus and compelled to face George and Martha’s shenanigans sitting right inside their living room.

Loud Mouth Theatre presented Theresa Rebeck’s Seminar, an incisive literary comedy that was a Broadway hit a few years ago. Directed by Maeve Mhairi MacGregor it was an entertaining, intelligent and well-designed production, although the script, for all its protestations to the contrary, is yet another take on the notion of ‘genius’ revolving around the male ego. Some fantastically overwrought moments included Jeff Keogh’s strong performance as the aforementioned archetype. This was also my first chance to see the newly built Moonah Arts Centre, with its Performance/Screen Studio offering a flexible new space.

Loud Mouth Theatre is a collaboration between three motivated twenty-somethings, MacGregor, Katie Robertson and Campbell McKenzie (MacGregor and Robertson returned to Tasmania post their training in Sydney). Loud Mouth is the new kid on the block, having launched in May 2014 with a production of David Ives’ Venus in Furs. They’ve achieved a lot in a short time, including a colourful response to Leo Schofield’s comment in an interview this year describing Tasmania as a land where “all the young people leave, and the only ones left are the dregs, the bogans, the third-generation morons” (Sydney Morning Herald, 4 April). MacGregor and co started a Leo’s Bogans campaign on social media profiling high-achieving Tasmanians under 35, of which there can be no better example than the trio themselves.

Leaving aside the fact that all three companies are under-funded and that the definition of professional here may sometimes include profit-share, here were three polished, ambitious productions—one was a new work, one (imported) written by a woman and one directed by a woman. One (imported) was by a ‘non-white’ playwright. One was staged in a pop-up theatre space (Red Rabbit, White Rabbit), one in the Theatre Royal, Australia’s oldest proscenium arch theatre (100 Reasons For War) and one in a brand new arts centre in the northern suburbs (Seminar). So whatever your aesthetic or critical response to the choice of material, there’s no doubt that what these productions represent is significant insofar as they embody a new spirit of experimentation. The experimentation might have been more around audience development and staging than about theatre-making on the deepest level, but nevertheless it’s promising.

But before celebrating, let’s remember that the effects of changes to Australia Council funding are about to bite. Tasmania will be disproportionately affected, because we don’t have any substantially supported theatre at the small to medium company level. The only Tasmanian organisation on the list of protected ‘majors’ is the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra. On the upside, the so-called MONA effect will continue, with increasing activity around festivals creating opportunities for artists. But as is the case with the film sector in Tasmania, the balance of imported and local work needs to be spot-on if all this is to really build, instead of merely inflating the sector artificially at certain times of the year. Theatre in Tasmania is going through a crucial period of transition—in a climate of upheaval and opportunity perhaps the biggest risk of all would be to play it safe.

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 42

© Briony Kidd; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

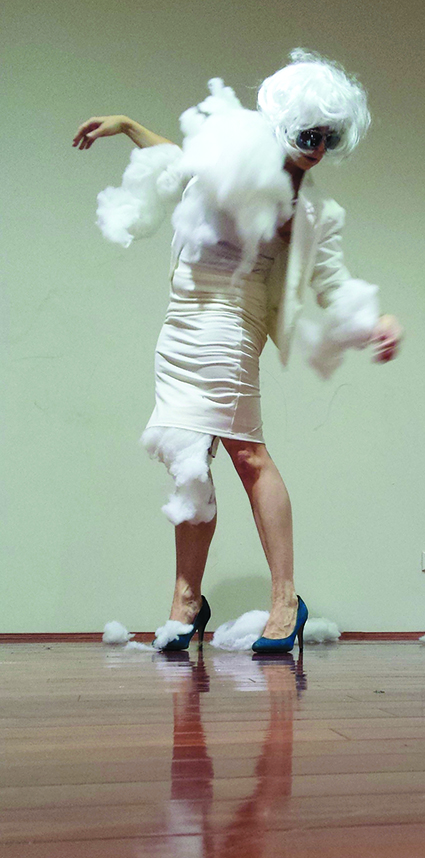

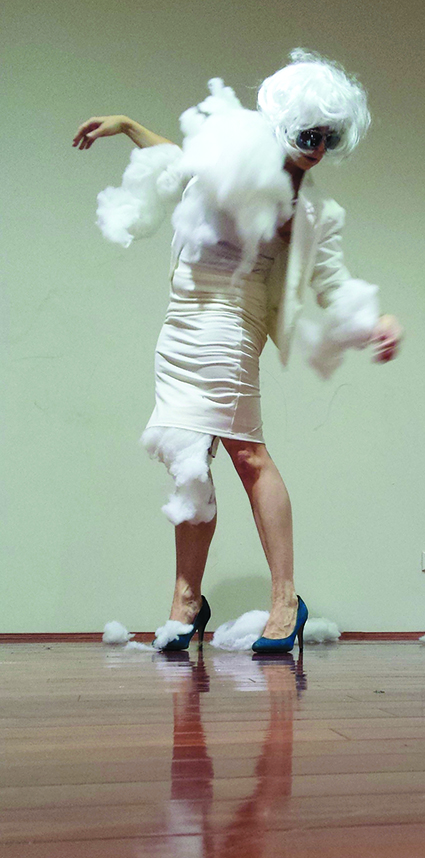

Nicola Gunn, In Spite of Myself, 2013, photo courtesy the artist

Nicola Gunn is a first-person performance artist. Since 2001 she has directed herself, performed herself and revealed herself. Sometimes she even tells the truth. But whether that truth belongs to her lived story or to the story of any number of Nicola Gunns in any number of alternative worlds remains uncertain. I don’t know. I am not Nicola Gunn. She has often talked about her mistrust of language, condemning its failures and inadequacies. Perhaps her inability to write narrative is why she chose performance art, as a kind of shorthand? She tells me, “My mother is a species of cat. She speaks a kind of cat language that not even the cat understands.”

Gunn works in an A5 black spiral notebook. She has a stack of 20, 30 maybe 50 of them in her IKEA Expedit. She uses a special pen in her notebooks: a .3mm black fineliner. People who know her know they must neither touch her notebooks nor use her special pen. “People often ask me when I’m writing in my notebooks, the pen in my hand, does it feel different? The answer is no. It feels like a pen.” She buys big rolls of newsprint, fills them with ideas and themes and then folds them up and puts them in a corner and doesn’t look at them again. She gets in a studio and generally spends three weeks in foetal position. She tells the girls in the waxing salon that she’s a graphic designer: “It’s difficult explaining to someone what you do when they’re looking at your arsehole.”

A woman of strong social ethics, yet very few personal morals, Gunn’s acclaimed body of work has always explored the role intimacy plays in geosituationalism. (I will discuss concepts of geosituationalism later on in this article.) And yet, pressed to define what she’s interested in, what she does and how she positions herself, she is enigmatically ambiguous: “I don’t know what I do or what I’m interested in.” The program notes to In Spite of Myself, her acclaimed work from 2013, offer some clues: “I spend a lot of time writing emails to community groups looking for old people. Last week I got in touch with Mary from the North Carlton Neighbourhood House and I told her I needed some old people for this show. She said, “What kind of show?” I said, “A show in a big theatre.” She asked me what was it about. I said invisibility, absence, irrelevance, the exploitation of marginalised sectors. She said old people don’t like going into the city at night. I said, have you asked them? She said leave it with me. At that point I realised I would not hear from her again.”

Further on, Gunn writes: “I’m concerned with social structures. I feel very strongly about working with real people and community groups, marginalised people and diverse demographics.” I’m not actually sure that is true. She has told me on numerous occasions that it was really really really really really really really really annoying getting the old women to commit and even more frustrating trying to schedule them because they never had their mobile phones on. She complained that they had their own logic for doing things that was totally out of step with the rest of the world. Like having mobile phones but not turning them on. Incidentally, old people do go out at night. I’ve seen them. They look like the visual representation of confusion.

By inviting the public into the act, Gunn is interested in subverting the economics of performance, where youth and celebrity determine interest. Her seminal 2012 work, Disappointment Mountain, continued the theme of cultural democracy evidenced in earlier pieces, such as Nicola Gunn Naps for Your Pleasure, in which an anonymous collector paid an undisclosed amount of money to have Gunn nap in their presence. Based on the success of the original performance, public demand to see the work and her commitment to dismantling the monetary emphasis throughout the performance art industry, she has repeated the event in various venues and continues to perform it regularly. (I was fortunate enough to see an impromptu performance myself during this interview.)

Nicola Gunn, Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster

photo Sarah Walker

Nicola Gunn, Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster

However, in Disappointment Mountain the audience is encouraged to make the work. The audience makes the art! It’s really exciting. The audience is content! Audience participants were encouraged to bring an object that represented a way in which they were unhappy in their life, or alternatively to create an unsatisfactory artwork and add it to the pile. They were then invited to take part in a one-off ceremony celebrating their dissatisfaction with the work. In this manner the artist reclaimed the theatre as a place where we form a temporary community and were inevitably let down by the experience.

Nicola Gunn says she hasn’t really thought about kids because she’s too busy. November will see her touring to Adelaide with a new work called Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster. Except she didn’t get all the funding, so she might just call it Piece for Ghetto Blaster. She recalls how an ex-boyfriend once told her watching her make theatre is like seeing how sausages are made.

She describes the motivation behind I’m So Happy, the single-channel video work commissioned by Arts Centre Melbourne to activate its public spaces: “One morning, I was telling my flatmate about the Arts Centre and I realised what an aggressively inflexible building it was. As I was making my lunch for the day, I discovered a bunch of limp celery in the fridge. I didn’t think too much about it.”

Feeling that success might dull the critical edge of her work, Gunn continues to have a vexed relationship with the economics of the art world, an acknowledged ambivalence that has only become more felt as the artist increasingly receives commissions and financial support from major institutions. When you operate in the established system, somehow you have to maintain your ethics, integrity and most importantly, independence. Otherwise you face the threat of irrelevance. You’ll see it out the window and you’ll wonder if it’s lost but then you realise, no, no, it’s looking for a number. And then you realise it’s looking for your number and then you hear a knock on the door. “Success has in-built limitations,” she says. Coincidentally, this is what my change and transformation coach advised me this morning over coffee. (God knows my expectations have not been met.)

Gunn says she doesn’t plan what she is going to make next. To do so would be an exercise in hopelessness. She says it just comes, or it doesn’t. “I have to go through a kind of transformation or emptying in order for the idea to come. It can be very difficult and painful. It is rarely joyful. It can take a very long time, much to the frustration of my collaborators. I just know it will come because it must. I only ever work to deadline.”

Pressed to offer some kind of insight into this foray into the many worlds of Nicola Gunn, I find myself participating in what she has perceptively termed an exercise in hopelessness. ‘Hopeless’ because all writing, all thinking, all talking about performance that tries to capture its slippery character is a hopeless endeavour. And yet, I am hopeful that this attempt at a critical dialogue with one of the great mythmakers of the present will offer one more disappointment to celebrate at its end. Please allow me to add this to the pile with my sincere well wishes.

–

Nicola Gunn/SANS HOTEL, Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster, Arts House, Melbourne, 11-15 Nov

Nicola Gunn is a performance artist, writer, director and dramaturg. She uses performance to reflect critically on its place in theatres, to examine power relations in existing organisations and to consider the relevance and social function of art itself. In August she premieres A Social Service at the Malthouse Theatre, a work set on a public housing estate. Her Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster, commissioned by Mobile States and presented by Arts House, is described as “the story of a man, a woman and a duck…It is an attempt to navigate the complexities of trying to become a better person” (press release).

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 44

© Susan Becker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Once We Were Kings

photo Mustafa Al Mahdi

Once We Were Kings

Pride shines through in intimate tales of love, loss, rejection and steadfast memory. Once We Were Kings presents a collection of richly evocative vignettes of life as experienced by gay Muslim immigrants to Australia. The fluent beauty of the language is a tribute, a call to bear witness and a seized opportunity to share stories.

Self-discovery takes many routes in these overlapping monologues, with specific details catching the heart and imagination—letters hidden in a pot plant, furtive holding of fingers under a pizza box (from the halal place) and the last memory of a grandfather. Common themes abound: rejection by fellow believers, rejection by lovers, loss of cultural identity with migration and loss of family connections. This small cluster of shared life experiences is marked by its acceptance of a diversity of voices. No single authoritative narrative dominates this sub-sub-culture, its commonality based in the suffering of social rejection and denial of personal validity.

Cashews and pomegranates—motifs of sweet and sour, pride and heritage—evoke memories flowing through more tangible recollections of regret and loss. Delivered direct to the audience in a stylised manner, the vignettes combine angst, nostalgia, anger, bitterness and humour. Concealing identifying details, names of people and places, dates and events beyond the confronting immediacy of the personal moments shared here, the stories’ contributors reveal the raw nature of their truths, still stinging nerves not yet ready for the bracing air of public scrutiny.

Three young actors, Angela Mahlatjie, Solayman Belmihoub and Naomi Denny, deliver demanding material clearly, without hesitation. The stylised manner of presentation removes some dramatic opportunities, but their delivery echoes the detachment necessary to survive some of the situations and frustrations. Director Mustafa Al Mahdi guides his cast to connect with the audience through a kaleidoscopic selection of abstractly styled, intimate moments—a challenge met with understated dramatic skill by the performers.

Using deceptively simple staging, Al Mahdi sacrifices potential dramatic vigour in favour of creating a visually arresting stage-scape. Dim lighting loses some details but conveys strong impressions, each performer’s body becoming part of the scenery, moving simply and deliberately. This overall stillness lends clarity to words, giving Dure Khan’s beautifully written free verse-script room to breathe, the strong, static stances impacting profoundly.

Thoughtfully composed projections enhance the sensation of large-scale installation with red drops pooling on a performer’s white gown, the recollection of a voice intermingled with water burbling from a corner and dimly traced dancers flickering on the wall—echoing the dim reminiscence of a first teen crush. The soundscape’s intense, rapid rhythms complement the pace of speech in some pieces with a pounding beat and amplify the angst in others with edge-of-awarness humming.

Khan’s richly lyrical script captures the difficulties of becoming a Crescent Moon-shaped peg in a Southern Cross-shaped hole and resolutely challenges norms of mainstream Australian society, the taboos of Islam and narrative expectations. Walking through the accompanying exhibition provides space for reflection and a continuing sensation of intimate and personal experience with childhood photos of the actors scattered through a pile of suitcases and belongings that evoke individual histories amid more abstract sculpture and photography.

Third Culture Kids have a voice, insistent to be heard. Once We Were Kings is a showcase of defiant pride, exploring artistic possibilities that challenge cultural and social expectations. Simply being part of the audience feels like witnessing a creative movement establish its own space in modern Australia.

Third Culture Kids and The Blue Room Theatre, Once We Were Kings, director, producer Mustafa Al Mahdi, writer Dure Khan, co-director Alex Kannis, lighting Devon Lovelady, sound design Thomas Moore, cinematographer Lincoln Russell, The Blue Room Theatre, Perth, 12-29 May

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 45

PQ Sign

photo Carlos Gomes

PQ Sign

Katia Molino and I navigate the flood of tourists in Prague, looking for the ‘blue chair’—the logo for the 13th Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space 2015. PQ is the oldest symposium of its type. In the program, Artistic Director Sodja Lotker states, “PQ explores scenography as a strong and invisible force of performance; a power that influences us just like music, weather and politics.” This year PQ broke the record for participation, with more than 90 countries represented.

The program is organised by a diversity of curators and events divided into the categories Tribes, Makers, Workshops, Talks, Objects, Performance, Show and Tell, Sound Kitchen, Countries and Regions. Katia and I represented Sydney’s Theatre Kantanka. We were invited to participate in the Tribes program, with costume art from Bargain Garden, Kantanka’s performance-collaboration with Ensemble Offspring. I also gave a talk about our process for making this show.

I’ll focus on Countries and Regions, where curators for individual countries were invited to explore the theme Shared Space: Music, Weather, Politics. With exhibits housed in a variety of buildings, normal geographical relationships were ignored: Estonia was next to China, Russia and Uruguay shared the same room. There was a sense of pleasurable chaos as we wandered around exhibits amid grand Czech architecture. On show were maquettes, LED displays and multimedia images and at times designs were transformed into surprising concepts.

Australian Exhibit A-Mass

photo Carlos Gomes

Australian Exhibit A-Mass

A-MASS, Australia

Climbing the stairs inside the exuberant Colloredo Mansfeld Palace, you gaze upon white clouds made of helium weather balloons floating on the ceiling. Images of the Australian sky (collected by the curator and designer of the Australian program, AnnaTregloan) are projected onto the balloons. Lured in, spectators are treated to a panorama of diverse works projected onto a large screen. The exhibit includes multi-media presentations, interactive sites and live events. The works have, as a common element, a participatory aspect to their performance structure: The Democratic Set (Back to Back Theatre), Resist (PVI), Yawn (Renae Shadler), Whelping Box (Branch Nebula, Clare Britton, Matt Prest), The Home Project (NORPA), The Shadow King (Malthouse Theatre), Super Critical Mass (Julian Day, Luke Jaaniste, Janet McKay).

Five Short Blasts by Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey, was originally created for the Yarra River in Melbourne. This elegant work was transferred to the Vltavu River in Prague where the makers collaborated with local Czech artists, including original interviews and text by Pavel Brycz and Tony Birch. We gathered early in the morning and boarded a rowing boat. Gliding down the river, we listened to composed sound as it blended with live music from the shore and the sounds of the waking city. This experience, with a surprise cup of tea and Anzac biscuit, was a delicious pay-off for having woken up at 5am to get a place on the journey.

M. Flynn, T. Humphrey, Five Short Blasts

photo Carlos Gomes

M. Flynn, T. Humphrey, Five Short Blasts

Theatre NO99, Unified Estonia

Entering a bright vanilla and beige room, you notice political posters and a party logo draped on the wall. As we step onto the shagpile carpet of a ‘stylish’ political party office, Estonia’s Theatre NO99 greets visitors and promotes their “How to take Power?” franchise (designed and directed by Ene-Liis Semper and Tiit Ojasoo): “Power is just lying there on the ground. Pick it up and make it your own.”

In 2010, NO99 created a fictional populist political party and convinced the nation that it would run for the national elections. The 44-day campaign was ‘reality theatre’ taking various forms—live appearances, media interviews, public interventions. Media interest in the ‘party’ sky-rocketed. The final performance was a ‘party convention’ attended by 7,500 people inflamed with nationalistic fervour—this despite NO99 openly saying their convention was a theatrical performance. NO99 attracted 25% of public support for their party in polls.

Estonia Exhibit, Unified Estonia

photo Carlos Gomes

Estonia Exhibit, Unified Estonia

The company had studied the techniques of political manipulation, copying the mechanisms of real politicians and applying them to their creation. At PQ, NO99 presented the results of their interventions: posters, videos and a ‘how-to’ guide to taking political power. This was clever, witty, humorous and ultimately frightening work. It is no surprise that Estonia won the Golden Triga for the best exposition—PQ’s top prize. [For excerpts of the subtitled performance see this and related links].

Post-Apocalypsis, Poland

Poland’s exhibit was the atmospheric interdisciplinary work, Post-Apocalypsis, curated by Jerzy Gurawski with a team of composers and designers. The installation consisted of several lopped tree-trunks supported by metal rods, creating a strange, decapitated forest.

Weather data was streamed into the space from locations on Earth where energy-related disasters have occurred, as in Fukushima and Chernobyl. This data was transformed into a soundscape for the installation and could be manipulated by the visitors. Also inserted into the trunks of the trees were sound devices. Pressing your forehead on these, classic Polish poetry reverberated in your skull. You were invited to reflect upon the relationship between nature, and technology—combining human and non-human elements to create a unique eco-system. Post-Apocalypsis won the PQ Gold Medal for Sound Design.

Post-Apocalypsis, Poland exhibit with Katia Molino

photo Carlos Gomes

Post-Apocalypsis, Poland exhibit with Katia Molino

Between Realities, Netherlands

The Netherlands chose to locate its PQ entry, Between Realities (www.betweenrealities.nl), in a corridor between the exhibition spaces of other countries and a toilet. This interactive publishing room shared information about public interventions that its artists and designers were instigating in Prague with selfie-spots, images of the suburbs brought into the city, white blobs filling alleyways, cardboard waste sculpting and undercover games, collective mapping using apps to track the movements of certain kinds of people. Daily ‘instant magazines’ uncovered the multi-layered realities and functions of public spaces in the city, suggesting how to participate in new realities. Printers were running hot, producing reports of findings while raising questions about the new realities of public spaces created by the artists. This was impressive teamwork involving a large number of artists—and surely well funded.

PQ 2015 Artistic Director Sodja Lotker and her curators made it possible for artists to create spaces in Prague for rich, diverse and inclusive cultural experiences while questioning the responsibility of scenography in the process. It will echo with us for a long while and deserves a visit next time.

PQ 2015, 13th Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space, Prague, 18-28 June; PQAU was an initiative of the IETM-Australia Council for the Arts Collaboration Project with support from Arts Victoria.

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 46

© Carlos Gomes & Katia Molino; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Bajazet

photo Keith Saunders

Bajazet

Vivaldi’s Bajazet is an opera you might be lucky to see staged once in your lifetime and there’s only one complete CD recording to date, but in the Pinchgut Opera production director Thomas de Mallet Burgess has radically changed the tenor of its ending to suit our own graceless times. Vivaldi’s ending is typically Baroque—after the playing out of jealousies, betrayal and violence, forgiveness and beneficence rule. For artists of the Baroque such endings weren’t simply feel-good clichés but reflections of belief and wariness of offending rulers in strictly monarchical cultures.

Not surprisingly then, 17th and 18th century English writers changed the endings (and more) of Shakespeare’s tragedies—most famously Nahum Tate, 1681, saves Lear and Cordelia marries Edgar. Adaptation is just as rampant today, with varying degrees of sensitivity. In Benedict Andrews’ Measure for Measure at Belvoir (2010), Isabella, about to be married to the Duke in a final tableau, steps outside the production’s video frame and runs for her life into the audience. The play, in the Andrews manner, is otherwise left pretty much intact unlike, say, Barrie Kosky’s radical rewrite of Lear for Bell Shakespeare in 1998 with evil absolutely triumphant. I welcome adaptations of classics—they’re well-known and we can respond to the intellectual challenges of directorial conceits. For lesser or barely known works ‘adaptation’ seems pointless. (I liked Thyestes [Belvoir, 2012], but what was it an adaptation of? Something far removed from the little known play by Seneca the Younger.)

Pinchgut’s Bajazet is faithful to the tenor of the libretto almost to the end, when Astrea, daughter of the defeated Turkish emperor Bajazet, and the Greek prince Andronicus, lovers hitherto under threat of violent deaths, are handed Greece and marriage by a suddenly benign Tamerlano. As everyone around them celebrates in glorious chorus, Astrea and Andronicus take poison, presumably unconvinced that the unpredictable Tamerlano’s beneficence is likely to be enduring. It’s an ending at once disturbing and irritatingly out of kilter with the strength of character revealed in the couple, particularly Astrea. Instead of fatalism the director might have opted for just as fanciful defiance with Astrea poisoning Tamerlano (the actual Timur was pretty much at the end of his nasty career). Who wants ISIS to win out over its courageous opposition?

I should have seen the ending coming. Looking pretty much like any number of Baroque opera productions of recent decades, this Bajazet is historically displaced, from 15th to 19th century, and given a quasi-Victorian look, the men in white and cream riding outfits, the women in (not very full) skirts, the simple set comprising a huge white bookcase on one side and an equally large double door opposite, both white. Furniture and statuary are scattered about and a high, wide red curtain hangs at an angle at the back—signs of pillage after conquest. There are oddities: Bajazet dressed in traditional Turkish attire, Tamerlano in European whites, not at all the Tartar, save the swagger.

However in Act II, the shelving has been cleared of books, the trophies of war displayed and Tamerlano, about to take action, dons Arabic head-dress and shortly appears entirely ISIS-like in black to condemn Astrea to rape and death by a mob. It’s a slow reveal of the extent of Tamerlano’s destructive vision from which Astrea and Andronicus feel they can never escape and therefore opt for death. The man they initially meet is not just another well-dressed conqueror. It’s not an altogether convincing logic. I would have preferred some consistency in costuming and an overall sense of clarity of purpose from the start as seen, for example, in Peter Sellars’ production of Handel’s Theodora—the conceit of the Texas capital punishment death machine is laid over the Roman persecution of Christians and immaculately realised, aesthetically and politically. (Theodora is scheduled for production by Pinchgut in 2016.)

Just what’s to be gained by setting Bajazet in the 19th century is never made clear. There are also plenty of distractions: Grand Guignol skeletons—Tamerlano’s victims—leaning in to watch from the balconies; too much dragging in, out and about of furniture by busy supernumeraries; a stuttering raising of the red curtain mid-aria in Act 1; and the sudden silhouetting and then tight spotlighting of singers as they hit the high notes of their arias—as if the singing could not carry the day.

Despite its conceptual and design flaws Bajazet nonetheless shone because of superb singing, acting, musical direction and period instrument playing. It’s to the credit of director de Mallet Burgess, conductor Erin Helyard and all the singers that the performances were so finely tuned, emotions clearly expressed and the oscillations between the private and public selves of the characters so well delineated. Despite the sprawl of the narrative and the too busy staging, the production dwelled intently on each moment while building tension towards a frightening conclusion, if one made fatalistically grim.

Orpheus Song, (L-R) David Trumpmanis, Ewan Foster, Stephanie Zarka, James Eccles, Geoffrey Gartner, Andrée Greenwell and Julia County

photo Matthew Duchesne, Milk and Honey Photography

Orpheus Song, (L-R) David Trumpmanis, Ewan Foster, Stephanie Zarka, James Eccles, Geoffrey Gartner, Andrée Greenwell and Julia County

Andrée Greenwell, Gothic

Since the late 18th century, the Gothic has never passed its use-by date, periodically rising wraith-like from the depths of the collective unconscious as high art, pulp fiction, fashion and youth sub-culture and nowadays overpopulated with vampires, werewolves, zombies and the common or garden ‘returned’ (see review of Glitch). One of the few practising stalwarts of Australian music theatre that is neither opera nor musical theatre, the ever-inventive Andrée Greenwell, premiered her Gothic during Sydney’s Vivid Festival. Hers is a quieter, subtler take on the genre than most, but still blessed with eeriness and occasional horror.

Gothic is a seamless theatricalised concert, its background three tall church windows (design Neil Simpson) which become screens for digital (and psychological) projections by London-based Australian media artist Michaela French. In the foreground is an ensemble of instrumentalists and two singers—Greenwell herself, often delicately ethereal, and Julia County, a soprano with a daunting range and enveloping delivery. I’ve limited myself to the songs and imagery which I thought represented the best of the concert.

In her folk/classical setting of Edgar Allen Poe’s Annabel Lee, Greenwell’s voice intertwines with violin as the land and seascape of “the sepulchre/in this kingdom by the sea” mysteriously mutates, the animation ‘panning’ from a small house on an island to a distant city to the accompanying lap of ocean waves as the teller “lies down by the side/of my darling…In her tomb by the sounding sea.” The Cure’s gothic rock “A Forest” (1980), one of the more frightening of the program’s songs, opens with the sounds of a child’s voice, crickets and “Where are you?” cries, conjoined with ghostly black and white etchings rhizomatically transforming into forest branches and shafts of light which seem to propel the accompanying strings.

Another lost soul—a child in the throes of being snatched away by a supernatural force —is the subject of Greenwell’s pulsing string quartet arrangement of Schubert’s The Erlking. Soprano and cello entrancingly share the melody while images of children in 19th century apparel appear and fade before the many windows of big city buildings—as if still with us as ghosts in our own century. Another lost to powers beyond the human is felt in poet Alison Croggon and Greenwell’s haunting The Orpheus Song, the composer adding the sound of responses to the 2011 Joplin Tornado in Missouri, USA as it struck, recorded on an iPad. A red line spreads and threads its way across the windows—a red path of destruction? Chosen Words by writer Maryanne Lynch and Greenwell is one of the strongest of Gothic’s compositions with its account of a woman kept in her grandfather’s cellar for 19 years. Greenwell and County vividly voice the sense of threat and the yearning for escape while a series of images of suburban houses flicker by, evoking a domestic banality of evil.

Gothic climaxed with Poe’s “The Bells,” the instrumentation resonating with the animations of huge bell mouths swinging towards us and then being rendered abstract, taking us with them into oblivion. Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks theme, “Falling” (1990), provided an apt coda to Gothic, a solo guitar arrangement with electronics for a composition as enticing as it is disturbing—which is the uneasy charm of the Gothic. Greenwell’s curation, composing and arranging made for a fascinating program not least in the engagement between live music and media art.

Pinchgut Opera, Bajazet, composer Antonio Vivaldi; City Recital Hall, Sydney, 4-8 July; Gothic, artistic director Andrée Greenwell, electronic processing David Trumpanis, Vivid, Seymour Centre, May 28-30

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 47

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Johannes S Sistermanns, Decibel Installation

photo Holly Jade

Johannes S Sistermanns, Decibel Installation

Coinciding with the soft launch of the Western Australian New Music Archive, the 12th Totally Huge New Music Festival unearthed gems from local, national and international musical milieus. Detailed reviews of these works by myself and mentored writers Alex Turley and Laura Halligan can be found on the Features page.

Festival Symposium

Attendees at the festival symposium were treated to accounts of Western Australia’s rich history of contemporary music-making, from the Noize Machin experimental warehouse nights to snapshots of composers, ensembles and the state’s contributions to contemporary percussion. The WANMA soft launch was an opportunity to reflect upon how best to capture the truly momentous amount of musical activity in Western Australia over the years. According to the project’s founder Cat Hope, the archive will eventually act as a curated repository for existing images, videos and information as well as cater for the increasing live performance documentation being produced every day.

The archiving of software involved in live performance was a recurring theme throughout the day, with no easy solution in sight. The ABC’s Stephen Adams remarked that a functional description of what a piece of software does may be more valuable than the original code in the long term. All the more reason to maintain a critical, written record of musical performances such as one finds in, say, RealTime. The day was rounded off with a beautifully sparse performance by Ross Bolleter on one of his famous ruined pianos.

Amour-Soundbridge

The cellist Friedrich Gauwerky’s Amour-Soundbridge program explored musical ties between Australia and Germany. Gauwerky himself embodies these ties, having lectured in cello, chamber music and New Music at the Elder Conservatorium in Adelaide, 1989–96. He also performed as principal cellist in the Australian ensemble Elision 1990–97. Gauwerky contrasted music by German luminaries Stockhausen, Henze and Hindemith with stunning works by composers of German origin who have lived and worked in Australia, including Thomas Reiner, Felix Werder and Volker Heyn. The concert showed that the distance between ‘historical’ European culture and contemporary Australian culture is not so great—just one or two generations, a teacher’s legacy, or a couple of boat trips.

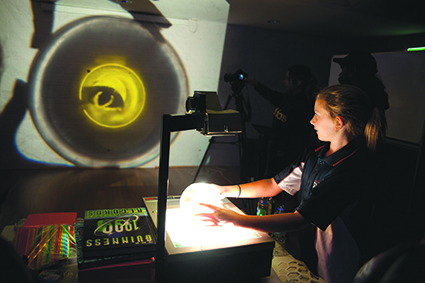

Space/Pli

Johannes Sistermanns’ installation performance with the Decibel ensemble Space/Pli provided yet another German-Australian connection. In Sistermanns’ installation, hundreds of metres of clingfilm partitioned the PS Art Space in Fremantle, the translucent film forming walls between the building’s pylons. Diagonal strips intersected the walls, striking down from ceiling to floor. Clingfilm has marvellous sonic properties, especially when paired with piezo transducers. The tiny vibrating discs were placed inside the folds of plastic, causing the rippling walls to buzz and shimmer. Decibel performed a graphic score by Sistermanns while spaced around the room. Their view of the score and each other was distorted by the film, introducing unexpected coincidences and affinities in the ensemble.

Club Zho

Tura New Music’s Club Zho program presents new music and sound art in a semi-formal environment, this time invading Jimmy’s Bar in Perth for a concert of escalating volume. Bass clarinettist Lindsay Vickery and percussionist Darren Moore performed as the duo Hedkikr. Despite the name, the duo are these days a picture of refinement and grace, crafting focused sonic duets of extended percussion and clarinet technique. Bassist Cat Hope and Vickery then defied all expectations of a polite classical duo. Performing under the moniker Candied Limbs, their 20-odd minute set was an explosion of irrepressible energy, featuring some truly unearthly screaming. Singapore-based modular synthesis duo Black Zenith (Darren Moore and Brian O’Reilly) conjured a staggering array of sounds and textures from their rats-nests of patch cables for the concert’s finale.

Zubin Kanga

I was fortunate enough to hear Kanga repeat the Dark Twin program at the Art Gallery of Western Australia two weeks after hearing it at the Metropolis New Music Festival in Melbourne. The electronic and live parts of Julian Day’s work Dark Twin were much more distinct under the soaring gallery atrium. Kanga’s interpretation of Hope’s score seemed much more fluid, like a Debussy Prelude flowing across the different registers of the piano. Hope’s EBows and radios also spoke louder than before. I don’t know whether these changes were brought about by Kanga’s gradual refinement of the pieces over time, my second listening or whether the composers altered the works themselves.

The Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts hosted two festival highlight concerts. The Breaking Out young composers’ night provided an excellent opportunity for Western Australia’s most promising young composers to test out new ideas. It was encouraging to see the level of mutual support between the young performers and composers as well as hearing the command with which the composers wielded their diverse musical styles. PICA also hosted the Melbourne-based vocal artist Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, who led Perth’s own iMprovisation Collective in a performance around PICA’s black box space before performing a solo concert in the venue’s dedicated concert venue.

Time Alone

Beginning shortly after the announcement of George Brandis’ cuts to the Australia Council for the Arts, the festival was peppered with the performers’ impassioned calls to action. The final concert, Time Alone, was no exception, featuring a stirring speech by Claire Edwardes. The concert was an eclectic tour de force for the percussionists Edwardes and Louise Devenish and the clarinettist Ashley Smith. With a well-known work by Ligeti next to works by Australian composers Michael Smetanin and Chris Tonkin, the concert captured the local-yet-international, looking-backwards-looking-forwards feel of the festival.

TURA New Music: Totally Huge New Music Festival, Perth & Fremantle 15-24 May

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 48

© Matthew Lorenzon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Common Eclectic, Clocks and Clouds

photo Felicity Clark

Common Eclectic, Clocks and Clouds

In one of nine Common Eclectic concerts staged by independent music promoter Places and Spaces in the refurbished Glebe Town Hall, Clocks and Clouds (Kraig Grady and Terumi Narushima) explored the sonic combinations available when an historic and now sound-proofed ballroom, metal bars and a homemade foot-pedalled organ meet. The instruments appear deliberately positioned to maximise resonance and audience interplay, the performance not so much ‘a work’ or series of pieces as a collection of structured soundscapes. My sticky-beak at their scores before the show revealed some written conventionally, albeit in shorthand, and others looking like pictograms and alphabetical pentograms. The music is theirs alone, in a language they have devised to facilitate experimentation in, and reaction to, their environment.

Grady only composes for instruments he himself has built, exploring ancient sacred scales, pure harmonic tuning and multidimensional geometries. Clocks and Clouds introduce us to a tree made of dangling metal chimes, a microtonally-tuned vibraphone and a set of seven bass Meru Bars that look like a plumber’s sculpture garden and sound as a glockenspiel must to a hummingbird. The music emanating from whooming, echoing bars—hung by elastic above vertical freestanding PVC resonators—induces a dull aching, if pleasurable vibration behind the eyes. Together with Narushima’s retuned and redesigned Meta-slendro Harmonium—a small foot-fanned keyboard instrument washed in pink and yellow paint—they interweave driving rhythms similar to relentless Thai court music or wind-chimes in a cyclone. The effect is glimmering and ephemeral—each vibraphone sound decaying so quickly that for the interplay of dissonances and aural-adjustments to take place, the pair must change pitches and rearticulate often. Pure harmonics glisten and bounce.

Grady knows his instruments inside out and uses their idiosyncrasies, particularly their harmonic interplay, to advantage. What’s special about this music is that while it is clearly mathematically and scientifically conceived, behind these calculations is a quest for aesthetic beauties and new frontiers of sonic sensation—it’s about the concept of perception before the abstractions and material manipulations that afford such perceptions come into play. The ways vibrations might feel are more important that the means by which they are harnessed. So while Grady and Narushima’s music looks and sounds very technical, pattern-laden and designed, its form is subordinate to the sensations it elicits—cloudy crepuscular impressions.

Though lyrical, Clocks and Clouds’ music had no words; Grady prefers listeners to infer what they will. Vocalist Karen Cummings of the duo A Body of Water says, “I look at the words first when I think about music, and am really interested in the intersection between ideas, music and politics. I want to perform music that speaks strongly to the world now.” She and Stephen Adams explored songs in many styles. They shared their passion for the intimacy and fragility of a song recital, “imagined as an exploration of the inner life through words, vocal resonance and breath” (program note). A Body of Water performed original compositions and re-workings of familiar tunes in unfamiliar guises. While Adams tinkered with mandolin, flute, piano, field recordings and electronic gadgets, Cummings’ soprano soared, her cross-genre specialisation and song-choices playing to her vocal strengths. She is an expert in cabaret song and is currently researching the impact of amplification on the performance of vocal repertoire.

Common Eclectic#6: Clocks and Clouds, musicians Kraig Grady, Terumi Narushima; A Body of Water, performers Karen Cummings, Stephen Adams; Glebe Town Hall, Sydney, 21 June

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 49

© Felicity Clark; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rihoko Sato, Broken Lights, Saburo Teshigawara, multimedia installation

photo courtesy Carriageworks

Rihoko Sato, Broken Lights, Saburo Teshigawara, multimedia installation

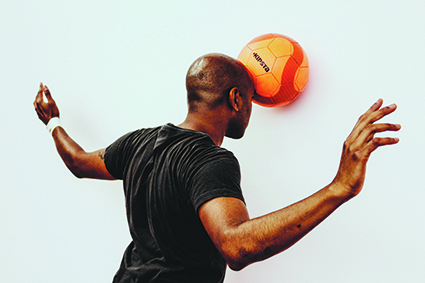

Carriageworks’ 24 Frames Per Second is immediately immersive. The foyer portal to this monumental exhibition of dance and visual art collaborations places the viewer between two huge screens on which football fans coalesce into swaying masses or lock arms and glide in a sideways dance at speed in Khaled Sabsabi’s Organized Confusion. They chant, sing, raise fists and strip off their tops at the urging of a muscular shaven headed leader—just another man in the crowd standing on a fence. The rhythms of sound and movement are mesmeric, although a sense of the restless power of the largely male crowd disrupts reverie in this record of crowd loyalty for its team, the Western Sydney Wanderers.

For all their activity, the fans are largely expressionless as they await play. For Sabsabi, their state is akin to trance. Bridging the screens with a series of engrossing near-still, black and white video portraits of Indonesian trance dancer Agung Gunawan, he creates a telling juxtaposition. Nearby, Brian Fuata’s mysterious Apparitional Charlatan…evokes in graphics, text and image fragmented memories from dance archives and of an empty, once-shared studio.

These three works prepare the visitor for the diversity of works that lie ahead in a vast, dark space lit only by the glimmer of screens near and far, lining walls and, in the centre, inhabiting an intimate labyrinth. The great space largely allows works to speak for themselves without interruption while occasional seating offers opportunities for restful reflection and earphones greater intimacy. The installation is a wonder, offering moments of discovery and fascinating juxtapositions.

Even after two visits for a total of some three and a half hours, I cannot do individual works in 24 Frames full justice nor can I cover all of them here. The number of works and their cumulative playing times prove a challenge, especially having to wait for long works to commence or finding one’s place mid-stream and returning later. Not all are narratives, but most have a structural logic which warrants sustained attention.

There are works I’m drawn back to. Singaporean media artist Ho Tzu Yen’s 1 or 2 Tigers (We’re Tigers) takes the form of a magnificent ‘weretiger,’ at once human and animal. Created from animation and motion and facial capture, it growls out animist and other philosophisings. Although the tiger’s movements are minimal as the camera turns slowly about it and we voyage deep into one of its seemingly sad eyes, the work’s thoughtfulness and focused imagery are deeply fascinating.

In White Record, Lizzie Thomson appears on an enveloping cluster of four screens. Accompanied by an engaging percussion track by Kevin Lo, Thomson offers a generous account of her personal archive of the jazz dance vocabulary in various permutations, from the intricately gestural to long loping walks captured in intimate detail by filmmaker Samuel James. The stark carpark setting and Thomson’s expression of deep concentration are reminders that jazz dance has long been abstracted into Modernist dance; but the artist’s movement subtly evokes the precision, energy and idiosyncracies of a vital legacy from black culture into white.

Sri Lankan Sydney-based artist S Shakthidharan’s Emergence celebrates female Yolgnu dreaming with layered cosmological imagery on a large wide screen divided at times into a triptych of dancing women and other maternal images evoking the giants who created the world and the sacred knowledge that men then stole from them. Young Indigenous men are portrayed as being at risk in Tony Albert and Stephen Page’s Moving Target. Inside a gutted car in the 24 Frames exhibition space, smoke drifts on the video screens which have replaced the door panels and the inside of the boot. A young Aboriginal man, a red target painted on his chest, dances—agile, finely angular, proud, defiant—and then falls.

The maintaining of cultural memory is also evident in the dancing of modern Berber women in Angelica Mesiti’s Nahk Removed, whipping their long hair to induce trance. Although the camera gradually pulls back to reveal limbs and faces, Mesiti is mesmerised by the hair—its length, textures, fluidity and especially its oceanic fullness when it fills the screen. Although beautiful in itself, the video might convey something trance-like but elides the real time power of the dance, the thrashing of the hair, because it’s shot in slow motion.

In Silence is Golden (cinematographer Bruno Ramos), Australian Aboriginal video artist Christian Thompson honours his English grandfather by performing a Morris Dance. Eye to eye with us and at near human scale, he dances with commitment, simply and subtly evoking overlapping indigeneities.

Challenges to the body are variously addressed. In Vicki Van Hout and Marian Abboud’s Behind the Zig Zag, glitches and stuttering pixelation yield richly coloured patterns. But these break up and compulsively loop the lyrical fluency of the sombre dancing. Projected onto the aged gallery wall, dance appears amid graffiti as just another piece of history done in by the digital.

Kate Murphy’s complementary large screen works, Lift and Push, juxtapose senior dancers Robina Beard and Patrick Harding-Irmer engaging with an automated body lift and commode wheelchair respectively. Beard appears to try to make sense of the device in which she is suspended, reaching out, touching its surfaces; Harding-Irmer assesses his, hits it and climbs atop its armrests as if the chair is something other than it appears. Murphy empathically and patiently portrays bodies and minds challenged by age.

Transferred from its performance staging to the screen, Branch Nebula, Matt Prest and Clare Britton’s Whelping Box expands, indeed queers, the realm of the Australian Gothic. Located in a mostly empty, aged house and surrounding claustrophobic bush, the film (cinematographers Denis Beaubois, Alexis Destoop) faithfully preserves the original’s brutal initiation of the human male into a surreal model of manhood. If less scabrously funny than the original, it’s a tense, finely crafted film with visceral impact.

Climbing challenges a dancer in Alison Currie’s I Can Relate for which the screen has been sculpted into rounded outcrops that synch with projections of rocky landscapes across which the dancer slides, stumbles and clambers, if sometimes with dancerly poise. It’s an engaging 2D/3D conceit. In filmmaker Sophie Hyde’s immaculately produced To Look Away, variously abled dancers from Adelaide’s Restless Dance Theatre adopt fantasy personae in meticulously matching furnished rooms pictured across five screens. These evocative live portraits entail sustained ‘at home’ stillness, restlessness and casual dance.

Of a small group of films in the documentary vein, James Newitt’s The Rehearsal, shot in a theatre in Portugal where the video artist from Hobart now lives, is the most interesting from what I manage to see of its 40 minutes. It records the making of a dance in which the bodies of trained and untrained dancers are subjected to increasing duress by choreographer Miguel Pereira. Positions are held and then slowly and sometimes agonizingly distorted. How the dancers accommodate this is revealing as is Pereira’s aim to create mental states to deal with the stress wrought by negative socio-economic conditions.

Natalie Cursio and Daniel Crooks, at least for a while anyway (still), 2015. Commissioned by Carriageworks for 24 Frames Per Secons

image courtesy the artists

Natalie Cursio and Daniel Crooks, at least for a while anyway (still), 2015. Commissioned by Carriageworks for 24 Frames Per Secons

Another senior dancer to appear in 24 Frames Per Second is Don Asker. In choreographer Nat Cursio and video artist Daniel Crooks’ at least for a while anyway, camera movement tracks left to right widescreen along a lakeside with its rushes and trees, until we reach a lone man, Asker, standing in the lake facing us. The camera moves on, the landscape gradually redistributed into striations of various greens, browns, blues and greys until the view is abstracted, although the water at times remains a ‘real’ if patterned presence. A hand pushes out between the lines and recedes, and then a leg, then head and shoulders, distorted like the melting limbs in Salvador Dali paintings but here coolly fluent, Asker stretching wide across layers of colour and over water in a series of supple moves. Asker’s dancing has been transformed, but the animation suggests agility, lyricism and even urgency. It’s one of 24 Frames Per Seconds’ best works. The ageing body emerging from and submerged in nature suggests a consoling and celebratory oneness.

Saburo Teshigawara’s Broken Lights engages me most of all, as both screen work and installation. It’s a work you step into to be enveloped by four screens—three walls and a ceiling—that reveal a field of sparkling, shattered glass on which the choreographer and dancer Rihoko Sato

perform. She is seen in the distance, then closer, human scale, elegantly poised in a supple, lean ‘vertical’ dance, feet shuffling ever so slightly over the glass in order not to fall. She then towers powerfully over the viewer. Teshigawara in black, mouth taped over, is a dark presence who breaks glass and executes an idiosyncratic little semi-crouched dance, the opposite of Sato’s. Broken Lights suggests much, for example evoking the creative risk shared by choreographer and dancer, if moreso physically for the dancer working with a choreographer who breaks rules—the fragile floor whereon new dance is made and performed.

24 Frames Per Second has delighted audiences but also provoked discussion that it’s principally a visual arts exhibition, with dance fuelling the making but being less than evident in the end result, where movement is fragmented, treated and often slow-motioned—phenomena, of course, not uncommon to screen dance, but felt in that field to be in the hands of choreographers and dance filmmakers. Discuss. Which we should do as time passes, allowing for reflection.

Congratulations to Carriageworks and its curators for an exhibition entirely comprising commissions of inventive collaborations and realised on a scale rarely seen in Australia, for installing it imaginatively and drawing attention to the multitudinous ways in which movement and screen can dance together.

Carriageworks, 24 Frames Per Second, Sydney, 18 June-2 Aug

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 50, 54

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Skunk Control, Gertrude Street Projection Festival 2015

photo Bernie Phelan

Skunk Control, Gertrude Street Projection Festival 2015

Google Maps reckons it’s a 10-minute walk, but with close to 40 light-based artworks floating, glowing or nestling along Fitzroy’s edgy and eclectic Gertrude Street, two hours was closer to the mark. And I’m sure I missed some. But playing ‘spot the work’ along the way, festival app in hand, was part of the fun. From seductive optical candy to the thoughtful, the political and the quietly sublime, this year’s Gertrude Street Projection Festival (GSPF) continued its development as a diverse creative platform for the conceptual, the spectacular and the collaborative across its 10 mid-wintry nights.

With civil twilight descending just after 5pm, mid-July Melbourne is perfect for an outdoor projection festival—wind, rain and single-figure temperatures aside. Gertrude Street is a concentrated location, the street itself providing some serious competition for the artworks. It’s a gritty, graffitied mix of hipster shopping strip and public housing precinct, dotted with bars, cafés, social services, galleries and hair salons, strung alongside a slow-flowing river of trams, bikes and cars. Lots of visual and aural distraction: moving headlights, constantly shifting noise and quirky store displays. But with a bit of online guidance, there was plenty of gold to be discovered within the busy substrate. Here are a few samples.

The Romantic

Brianna Hudson’s Place of Longing was arresting for both its subtle colour and shining Romanticism. Utilising light not to dazzle but to brush its pastel warmth against a pale laneway wall, Place of Longing depicted an ancient landscape slowly drowning in smoky, peachy skies. A near-static, painterly surface of shifting tones, it silenced the din of the street; inner-city grime giving way to Romantic nostalgia, lost forests and dissolving clouds.

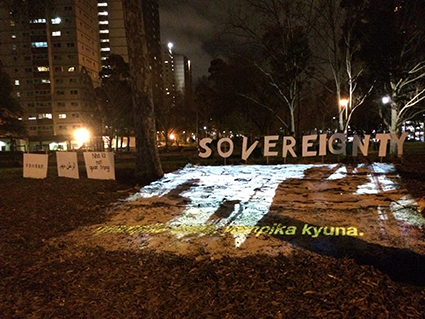

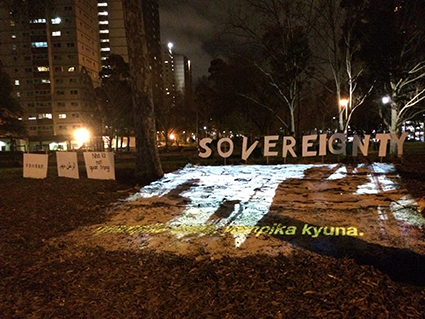

Gabi Briggs, Urala

The Political

Gabi Briggs’ Urala, sited amid a group of gum trees at the frontage of the Atherton Gardens public housing estate, used video footage from the recent Forced Closure rallies, projected against a carpet of paperbark and sand. Subtitles were included in Vietnamese, Arabic and Mandarin, aimed at creating dialogue between these local communities, as well as in Briggs’ own Indigenous language, Anaiwin. Behind the horizontally projected video, large letter-signs spelled out “SOVEREIGNTY”—the only English word in the piece. In a location where a long history of urban Aboriginal community intersects with those of recent migrants, the disenfranchised and the upwardly mobile—under a stand of trees suggesting a time before white settlement—Urala was spot-on in calling attention to notions of place, community and ownership.

The Collaborative

Briggs was one of four artists involved in GSPF’s Mentorship Program this year; another was Atherton Gardens resident Guled Abdulwasi, who worked with projection artist Nick Azidis to create giant ‘dark’ images on the side of the estate’s multistorey apartment buildings. I spoke later to GSPF co-curator Yandell Walton about the festival’s aim to bridge the social divide between housing estate and café strip. She cited festival projects including the mobile exhibition space Artbox Truck, situated within the housing estate, and presentations of performance/projection installations as well as an open projection night, Video Jam—which “allowed the exchange of ideas on a public art platform from the local community.” A ‘choose your own adventure’ work was also created around the estate by local youth theatre company Uprising Theatre; sadly, I was unable to catch these works but their inclusion augurs well for increasing connections across Gertrude Street’s many communities.

The Gallery

The New Vanguard exhibition, at Gertrude Street’s Seventh Gallery, showcased the work of five artists; drawing some 4,300 visitors during the festival, according to Walton. She and exhibition co-curator Arie Rain Glorie were keen to encourage the general public into a gallery space. Walton said, “For visitors to the festival to be exposed to conceptual works…this show was also about embracing projection as more than a medium used as spectacle…” From Tara Cook’s hovering, saturated, shadowy figures on a portrait-format video screen—who turn out to be ourselves, the viewers—to Zoe Scoglio’s bubbling, rumbling electronic paste-up of geometric shapes, stone, water, grain and flow (titled Water Falls and Other Features), The New Vanguard expanded the festival’s brief to include the projection of ideas: a counterweight, as the curators’ statement suggests, to the constant projected suggestions of advertising, politics and the “busy world” we’re constantly caught in.

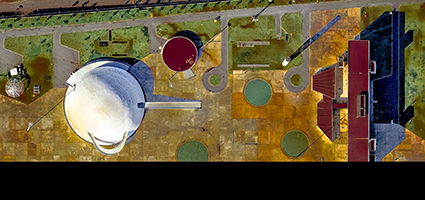

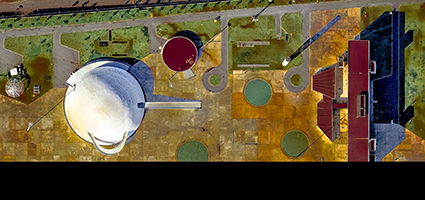

Ultradistancia, Federico Winer

photo courtesy of the artist

Ultradistancia, Federico Winer

The Polished

Amid mesmerising façades of swirling psychedelic colour and sneaky infiltrations into shop windows, two relatively ‘traditional’ works stood out while also fitting seamlessly into GSPF’s overall blend. Half-obscured inside a clothing store, Federico Winer’s Ultradistancia was no more than a vivid slideshow of enhanced aerial stills of cities, landscapes and roadscapes; studies in line and colour that were, nonetheless, just too good to pull away from. Similarly, in the front windows of Gertrude Contemporary, dance-filmmaker Sue Healey’s simply but perfectly realised film portrait of dancer Benjamin Hancock, from her On View series, drew a constant crowd of watchers, as Hancock moved and swayed like a tai-chi master or praying mantis, meeting our gaze as he floated, uncannily close to life-size, upon a dark and seemingly infinite background.

The Enchanted

And of course, there were the works, as always, that revelled in the mystery, pleasure, play and playfulness that participation in GSPF invites. Freya Pitt’s Fortune and Love Favour the Brave created a “Fake Hole” in a laneway wall: a metaphorical ‘lack’ into which was projected an animated reflection on desire—complete with photo-collaged angel lovers flexing their wings, riding on rocks and clouds and seemingly helpless amid their world of starscapes, graphics and flowing ribbons of text. Nearby, Victoria University’s engineering- and science-based collective Skunk Control utilised stark white light on black to create a magical, surreal grotto, Secluded Evolution, full of bizarre alien flowers in black metal, centres glowing with sharp monochromatic patterns. Upon them, black mechanised butterflies rested with transparent, stencilled wings pulsing, catching the light and splitting it into subtle prisms. Children and adults alike were transfixed.

The Couch Potato, Andre Fazio

photo Bernie Phelan

The Couch Potato, Andre Fazio

The Thematic

It’s impossible to cover even a substantial number of GSPF’s works in a short review, or to convincingly generalise on the themes and ideas at play. Walton saw, overall, a desire by artists “to investigate ideas related to technology itself,”mentioning works like Dalton Stewart’s painting/projection work Ontology, which “blurred the boundary between materiality and virtual space through the convergence of painting and projection.” I saw ideas-based work; work in which light was merely an element; work in which light was both primary medium and focus of investigation. The works that stood out for me were those that evoked other artforms, times, places; merged with and utilised the surfaces they played upon or the 3D spaces in which they sat; and gathered an energy—whether quietly or spectacularly—that overrode the peak-hour traffic and nippy weather. It’s a hard call to bring together the rough edges and consumer culture of Gertrude Street, but the high-rise flats, the bundled-up pre-schoolers, the commuters, locals and the dancing colours all seemed to be embracing a good time.

Gertrude Street Projection Festival, director Nicky Pastore, co-curators Yandell Walton and Kym Ortenburg, Fitzroy, Melbourne, 10–19 July

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 51

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jason James, Crevasse, envelop(e)

courtesy the artist and Dark MOFO festival

Jason James, Crevasse, envelop(e)

Matt Warren’s show Envelop(e) at Contemporary Art Tasmania is very much a culmination of ideas he’s been investigating for much of his career. His own work has long featured sound, so the move into curation in 2012 with A Silent Way seemed logical and has been revealed in Envelop(e) as a rich extension of his overall practice. Jason James, another Tasmanian artist who is at a much earlier stage of his career, contributed a new work to Envelop(e) while also debuting an ambitious installation, Angry Electrons, in a docking bay at the Centre for the Arts (see Profiler 11 at www.realtimearts.net for more on the artist and video of the work).

Envelop(e) comprises four sound works from Elizabeth Veldon, Christina Kubisch, Mick Harris and Julian Day, plus Jason James’ light installation Crevasse. While each has its own governing set of impulses and logical formatting, a powerful overall effect is realised by Warren’s careful arrangement of the works in a sparely lit space with open cubicles somewhat akin to listening stations—three of the four each with a small seat. The effect is monastic. Hanging at the centre is James’ Crevasse, a bank of 21 stage lights—1000 watt Par Cans—changing hue, seeping on and off. The overall arrangement of the exhibition implies ritual, attempting to slow viewers down—a seat probably helps, but it’s the setting that largely creates the palpably reverential tone.

Elizabeth Veldon’s The Tortoise History of Our Voyage stands out by breaking the sound-art mould, using texts gleaned from the journals of Charles Darwin on his visit to Hobart in 1836. Voices overlap and interlock, leaving potential for listeners to ascribe new meanings or just enjoy the cadences. Mick Harris, famed as the drummer for the extreme metal act Napalm Death, contributes two interwoven drone works that evoke the edges of dream worlds, while German composer Christina Kubisch presents sound from her installation Movements to Distant Places, an exploration of the sounds generated by the electromagnetic forces that shift around us. As with Veldon’s, both works create a spectral sense of the distances of history, geographic dislocation or the melting worlds of the subconscious.

Julian Day’s visually and sonically delicious Requiem features two identical “heirloom” synthesizers mounted on opposing walls and linked by eight silver rods which hold down keys, generating a drone. This sculptural work combines wit with a take on classic minimalism, becoming one of those ‘anyone-could-have-done-it-but-they-didn’t’ works that stand out as being in equal parts beautiful and clever.

Jason James writes, “Ever since hearing about explorers dying by falling into crevasses I have wondered what it must be like to be dying somewhere that is both beautiful and deadly”. An attempt to render the light seen from the bottom of an ice cave, Crevasse rolls slowly through cool and frozen light states: blues, stark whites, toxic lilacs. It felt cold, very cold. Its strongest effect is as a kind of visual subtext to the softly meshing sounds of the gathered art works that becomes the slowly pulsing centre of the room. The brazenly open display of the light source just above the heads of visitors, calls to mind a weird aircraft, possibly with occult or alien origins, its patternings reminiscent of coding or signalling—oddly triggering a desire to decode. Matt Warren’s art has long attempted this kind of evocation and it’s a fascinating eventuality that one of his most successful efforts should come from his work as a curator.

Jason James, Angry Electrons

courtesy the artist and Dark MOFO festival

Jason James, Angry Electrons

At a docking bay in the Centre for the Arts, James’ large-scale installation Angry Electrons marries motion sensors to a floating sea of 1000 light bulbs in a dance of glowing electricity that moves above in reaction to the audience moving below. Bristling with rude and lively energy, Angry Electrons successfully achieves something extraordinarily complex in technical terms if not in evoking the danger of electricity the artist intended. The many people who saw this installation almost universally played with it—children in particular ran about, delighted as they realised their movements were causing the brisk dancing above their heads. The potential for realising electrical terror might have been effected by hanging the bulbs lower, but practical issues of health (the effects of intense light on eyesight) and safety (the risk of someone touching and breaking a bulb) required the angry electrons to be contained by elevating their glass cages.

The stark concrete docking bay was transformed into a space of fleeting beauty, filled with excited, giggling shrieks; humans are possibly less predictable than electricity. Angry Electrons was not frightening, but thrilling, fun and incredibly engaging. James’ Crevasse felt far more sinister, conjuring up a sense of the irrational and the eerie.

Dark Mofo 2015: Envelop(e), curator Matt Warren, artists Elizabeth Veldon, Julian Day, Mick Harris, Christina Kubisch, Jason James, Contemporary Art Tasmania, 11 June-19 July; Angry Electrons, Jason James, Centre For The Arts, 12–21 June

RealTime issue #128 Aug-Sept 2015 pg. 52

© Andrew Harper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alterland, Heath Franco

photo courtesy Australian Experimental Arts Foundation

Alterland, Heath Franco

Video became established as an art form in the latter half of the 20th century, but in the 21st, the age of video games, virtual reality, YouTube, social media and phone cameras, video is a universal language. Performance art frequently explores identity and the self in interaction with the world, and in his review of PP/VT Performance Presence/Video Time, Ben Brooker notes the current resurgence of performance art, whose history is intertwined with that of video. Heath Franco’s work both extends the tradition of performance on screen, using himself as the actor, and addresses the ever-expanding field of visual media.

On entering Heath Franco’s Alterland, we first see Portrait (2010-2015), a three-minute looped video showing in rapid sequence the comically nightmarish characters he has created over several years. This sequence is framed by TV test-pattern colours as if TV or video portraiture has displaced painted and photographic portraiture. Sydney-based Franco plays every role, which he evokes with dramatic gestures, bizarre costumes, garish makeup and sometimes novelty-shop masks. His characters resemble caricatures from children’s stories, pantomimes and video games. There are many animal characters—cats, dogs, wolves and koalas, even a pig with a plastic roast chicken on its head. Sometimes Franco dresses as a woman, albeit with a beard. While there is a childish quality in this uninhibited foolery and dressing up, the characters represent personas we might encounter that can reveal the human psyche in all its manifestations. Franco says that they represent people he has met, or characters from TV and horror movies, and he cites David Lynch as an influence. His work brings to mind satirical comedy from Aunty Jack to Dame Edna Everage, Dada, Fluxus, Absurdist theatre and even the dissociative psychopathology of Jekyll and Hyde, as if Franco himself embodies a range of alter egos.