Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Key image, Miss Universal

Atlanta Eke

Key image, Miss Universal

Atlanta Eke’s work tends toward the hybrid. It’s the essence of her choreography, drawing visual, sonic, new media and conceptual forms into new relationships of exchange with the dancing body.

“I’m probably more cerebral,” explains Eke, who last year won the inaugural Kier Choreographic Award. “The practice for me is concept first, image, relationship and then once we’re there it’s really a lot of learning.”

Is this a dialectical practice? Concepts are placed before and against images and relationships: the concept is transformed and ultimately transcended. But the synthesis, the thing which happens during the performance, remains haunted by what came before. This unsettled quality is a hallmark of Eke’s work. Those striking, unforgettable images—say, the troupe of naked women with black hoods obscuring their faces dancing to Beyonce in Monster Body (2012), or the slow-motion ballet for cars in The Death of Affect Restaged with a Return to the Japanese Nude 2017 (2015)—are shot through with intimations of something profound but elusive.

The work seems to invite interpretation, but no paraphrase can comprehend the experience. It always feels as if you’ve missed something.

For her latest work, Miss Universal, commissioned by Chunky Move, Eke cites the inspiration of thinkers such as Carolyn Merchant, Monique Wittig, Donna Harraway and the Spanish philosopher Rosa María Rodríguez Magda. It’s a diverse bunch, not easily reconciled, but Eke’s creativity is good at translating multitudes.

The work had its first incarnation earlier this year at Gertrude Contemporary. Pip Wallis, a former curator at the Fitzroy gallery, saw a short work of Eke’s—Fountain (2014), also at Chunky Move—that reminded her of the sculptor Claire Lambe, and she invited the two to make a collaboration.

“They were trying to figure out ways to exhibit their studio artists in different ways,” explains Eke. “I met with Claire and began this conversation on how we can work together and I came up with this Miss Universe idea, trying to appropriate the format of the Miss Universe competition as a model for another kind of cultural, transnational happening.”

That was in March of 2015. The work has since been completely revised for Chunky Move, but Eke is still attracted to the idea of an unconventional (or convention defying) theatre space, a space that’s more like a gallery.

“I guess the interest for me is the social ritual and that was why it was fun starting at Gertrude and having the audience in a choose-what-you-want-to-do kind of space,” says Eke, who has created work in a number of galleries over the last couple of years. “You’re asked to come in and do a 20-minute show in a gallery and people are just leaning against the walls and sitting on the floor, and it’s just like, ‘why can’t we do that more in a theatre?’”

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

photo Sarah Walker

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

Despite the attraction, she’s aware that dance audiences may not respond to the offer of freedom.

“It’s kind of a delicate thing,” she says. “We’re going to find out a lot about it by doing it. I want the initial entrance into the performance space to be a kind of uncanny experience. It’s going to be a replication of the space that they’ve just been in. There’s an interest there in a certain kind of violence: feeling like you don’t know what you’re supposed to do, undermining habituated behaviours. But, yes, there are a lot of performances which already have that freedom, and it has become a convention in and of itself.”

Once inside the space, Eke—along with performers Annabelle Balharry, Chloe Chignell and Angela Goh—is proposing an exploration of different ideas of the universal. Is it possible to recombine the fragmented moments of recent history as a new universalism? Is it desirable?

“What we’re trying to practice is transmodernism,” she says, with a nod to the work of Rodríguez Magda. “So, in relation to dance history, it goes modern dance, postmodern dance and now transmodern dance. I think this is how one could propose a new universality for today, to reclaim the sincere, progressive and positive aspects of modernity. We’ve been like, ‘Dance your memory of postmodern dance.’ And it’s the usual fragmentation. Let’s see what happens when we piece it back together.”

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body, Dance Massive, 2013

photo Rachel Roberts

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body, Dance Massive, 2013

This kind of focus on the conceptual level can make Eke’s work sound more difficult than it is. In fact, her work is best characterised by its humour. There is, for instance, the section in Body of Work which looks like (or rather sounds like) one long fart joke. Or there’s the infamous scene in Monster Body where she reclines like a painter’s odalisque in a spreading pool of her own urine.

To the extent that the work is difficult, it is not because of a deliberate refusal to communicate. Eke and her collaborators know how to create a powerful connection with the audience, something absent from so much contemporary dance. It is one of the paradoxes of her oeuvre that what can seem at one level like cynicism or critique, can also have an attractive naive quality, like an earnest yearning for progress, for a genuinely communitarian, feminist future. And what better vehicle for hope than comedy?

But there is something urgent and sincere about the work. It’s not necessarily emotional or expressive, but there is an insistence through which the need for action is underlined. In Miss Universal, this comes across as a preoccupation with the theme of love.

“The thing is about love,” says Eke. “So we have these conversations where we focus in on the individual and love and then out on this idea of love as this other undefinable energy that attracts everything in the universe together.”

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

photo Sarah Walker

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

For Eke, love is the force which enmeshes and interconnects. It encompasses all the fragments and fugitive lines of a world without an organising centre. It gives coherence to the chaos. But is this only an artist’s figure for the absolute spirit, a way of explaining the mysterious unfolding of her own dialectical avant garde transaesthetic practice? There is a sense in which every artist yearns to be Miss Universal.

“The mission is to produce something unknown,” she says, “which is in the journey where it goes from the theoretical, cerebral thing to the art thing. But there’s something tricky about that—how do you do that without alienating people?” Maybe the only sincere way of doing it—all corniness aside–is to admit that the answer really is love.

Chunky Move, Next Move Commission, Atlanta Eke, Miss Universal, Chunky Move Studios, Melbourne, 3-12 Dec

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg.

© Andrew Fuhrmann; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

still from Michel Van der Aa's The Book of Sand

In soaring song-speech, Kate Miller-Heidke intones Jorge Luis Borges’ The Book of Sand with fragments from other of his stories. She’s the lone figure (except when she encounters herself) in Dutch composer and multimedia artist Michel Van der Aa’s engrossing interactive online video work commissioned by the Sydney and Holland Festivals and made freely available online (give it time to download—watch the timer bottom left).

Playing a Borgean Alice, Miller-Heidke is lost in overlapping worlds that constitute the infinity of the endless book the writer conjures and which consumes its reader. She runs circles on desert dunes from which shoot translucent strips inscribed with arcane script. But, like Alice, she is actively curious. In one room she herself ‘writes’ the symbols on the blank ‘paper’ by gently pouring sand onto it; in another she prints the text with sand as if it is ink, adjusting a bizarre printer with switches that break up the soundtrack. The sense of the infinite and corresponding material impermanence is haunting, made moreso when time reverses. Our narrator falls asleep, the ‘paper’ slipping serpent-like around her and rising in a grainy mist of sand—a thin column of it flows up from her brow and then another from her open mouth as we hear her sing “I saw the Aleph.”

still from Michel Van der Aa's The Book of Sand

The musical accompaniment is propulsive nigh jazz-rock minimalism—more lyrical than chugging—over which the singer’s voice flies with infinite ease, although the text is tightly scored to suggest looping recurrence. Miller-Heidke sings solo or is double tracked or finely accompanied a capella by the 12- voice Nederlands Kamerkoor, adding a sense of the sacred that comes with notions of the infinite and the curious mysticism conjured by Borges.

The writer’s devotees might find the dramatising of his work an overloading of the magic his writing already coolly and ironically invokes. For newcomers Van der Aa’s creation might be a welcome initiation.

The interactive element allows the viewer to switch between locations or you can just let the work run—until you feel the need to break out into another space or return to one more closely. Miller-Heidke’s singing is lucid but there is a subtitle option, English or Dutch, if you wish.

Michel Van de Aa’s The Book of Sand, “a festival gift to Sydney,” says director Lieven Bertels, is well worth entering for its peculiarly attractive evocation of disorienting relativities which make us feel small—save for the sheer scale of our prompted imaginations—or exist not at all: “I saw all the mirrors on earth and none of them reflected me.”

still from Michel Van der Aa's The Book of Sand

http://thebookofsand.net/

Michel Van der Aa, The Book of Sand, free interactive digital artwork, Sydney Festival, 2015-16

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. web only

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dancing in the Now – Full Length from Ubuntu Samaya on Vimeo.

Pippa Samaya is a 27-year old recent RMIT graduate in commercial photography who has made an engrossing, self-funded and ambitious 50-minute documentary, Dancing in the Now, freely available online.

The film features interviews with dancers—Stephanie Lake, Antony Hamilton, Paea Leach, James Vu Ahn Pham, Lauren Langlois, Tara Jade Samara and Sarah Jayne Howard—interpolated with footage of rehearsals and performances. The dancers speak lucidly and frankly about emotion, intelligence, risk, structure and, above all, dancing in the moment, the now. For artists who declare they prefer the language of movement and gesture over speech they are remarkably eloquent. Other dancers will recognise themselves in their words and young dancers will gain some sense of what lies ahead of them or is already felt, if not yet expressed.

Save for some passages shot in slow, fast or staccato motion (which are only occasionally revealing), the cinematography is fluent and engaging, capturing the energy and delicacy of movement of highly skilled dancers, alone or in groups in rehearsal, dropping in and out of the action, stretching or happily communing.

The film is structured as a series of episodes, each broadly addressing a theme, opening with the dancers’ embrace of contemporary dance’s openness, its capacity to “draw from raw emotions” without, says James Van Phu, “the illusion of smoothness” associated with ballet. Elsewhere Antony Hamilton says he’s come to reject the utopian goal of perfection,”of trying to find contentment in the next moment,” rather than now. “There is no destination. Then you can allow disorder into the work or your life. Let in mistakes and they can become the focus.”

In a section about emotion, Stephanie Lake speaks as a choreographer who “starts with something abstract and simple and ends up somewhere emotionally mysterious,” finding “emotional logic through structure.” Sarah Jayne Howard creates from feeling, but also, she says, from text “with its useful rhythms” and from the environment, as when “replicating a sweeping landscape.”

Samara speaks of the limits to emotional engagement in dancing; it can be too strong and draining physically—“sometimes it’s like an injury…but can also be healing—anger and love can give us the energy to move.”

As for being in the ‘now,’ it’s not simple. Samara speaks of “letting go and being in your body, but also of ”a certain skill in riding the experiential wave of awareness on a sensory level and letting go all the judgment as to what that is.” The performance is both ‘predetermined’ and in the moment.

For Antony Hamilton, the ‘now’ is in dance’s capacity to “shift thinking out of the everyday.” Several artists, like Paea Leach, speak of how much they are continuously ‘in’ their bodies in ways they think non-dancers are not. As if to underline this we watch a lone figure in a railway station performing tai chi while travellers speed by. One dancer evokes the physical intimacy of dance, of working so closely with other bodies in the moment but also“of coming home smelling of someone else’s sweat.”

There are reflections too on the ‘now’ of performance—Sarah Jayne Howard amusingly recalls times when she wondered if the audience would want to see her yet again, and Stephanie Lake speaks about periods of doubt but finds herself still a committed dancer.

What appeals to Tara Jade Samara is that dance now has “a contemporary intelligence and understanding of the body, and which changes” as our bodies evolve, moment to moment.

Tara Jade Samaya and James Vu Anh Pham, Dancing in the Now

photo Pippa Samaya

Tara Jade Samaya and James Vu Anh Pham, Dancing in the Now

Interview

You travelled widely at a young age. Was that influential in your becoming become a photographer?

My parents have always been adventurers of the world and as a child I was whisked along with them. Exposure to incredible cultures such as Nepal’s and trekking in the high Himalaya’s quickly opened my mind to the vastness of human experience. Also like my parents, I have always been artistic and, specifically, visually inspired. It was a natural progression for me to photography and film.

What specifically led you to photography?

I had an early introduction to photography via my father, who although he never went professional, shot incredible images all through his travels and has helped nurture my own interest since childhood. Studying commercial photography at RMIT was really just the final step moving me into the high-end professional realm of image making.

What is your focus as a photographer?

Although photography can be seen as superficial, I have always been interested in reaching further than skin deep. I strive for imagery that uses physical form to depict and inspire emotional states of being that cannot be seen but will always be felt. To achieve this and survive in the commercial photography world can be hard but I find increasingly that I attract the kind of companies and individuals who also share my values.

Why did you turn to dance? Are you a dancer?

Dance seems to me to be the perfect vessel to communicate the internal human experience through external expression. I’ve always danced, non-professionally, and loved it on an experiential level, but it wasn’t until I started to shoot dance at a high level that I really discovered just how powerful a still moment in this form of movement could be, and how many stories the body can tell. My partner is an incredible dancer and in recent years I have found myself increasingly surrounded by dancers and dance in many shapes and forms. It seems like a path that has been paved out for me that I am honoured to walk on.

What prompted the shift to film?

Working with dancers has led me in a natural progression to film; movement can often tell a whole other story from a still image. Once I began, there was no looking back. Although of course I still love still photography, I am now equal parts a videographer.

I approached several people I knew or had been referred to in the industry and many welcomed me warmly into their worlds. Throughout the interviews I was touched by some of the depths that we naturally moved into. Dancers are an incredible breed.

The dancers were generous to speak with you but also allow you to film them.

I did not ask for or require any previous footage of their work but many let me in to shoot my own throughout their rehearsal processes or even dress runs and performances. I would offer some still images in return, so we all left happy.

Where will your vision take you next?

As well as continuing to work in dance films and music films, I hope to take this project to a larger scale and eventually, with a little support, realise my dream of a film which documents and explores dance internationally—to explore the different uses for dance, social and traditional, for ritual, healing, spiritual, career, passion and romance, and how this reflects the humans who engage in it. Perhaps we will even reveal a cycle, which connects the individual back to the whole and exposes the interconnectivity of all life. Who knows?

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg.

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“New Physics is an online exhibition that presents ten Australian artists who produce a collective though diverse aesthetic investigation of the dislocative effects of the internet, and the many unlikely collisions it has created.” New Physics, Introduction, Roslyn Helper

“New Physics is an online exhibition that presents ten Australian artists who produce a collective though diverse aesthetic investigation of the dislocative effects of the internet, and the many unlikely collisions it has created.” New Physics, Introduction, Roslyn Helper

Sydney-based artist and curator Roslyn Helper has enterprisingly initiated an online gallery, New Physics, promising a series of exhibitions which open with extant works by Joe Hamilton, Alrey Batol, Josh Harle and Louise Zhang alongside works altered for an online context by Kusum Normoyle and Holly Childs and Stephanie Overs. Also featured are an ongoing work by Giselle Stanborough and commissioned creations by Ellen Formby and Peter Wildman.

Stanborough’s unfolding Instagram work is a series of often droll collages frequently connected by a pricked thumb motif, suggesting vulnerability, magic and blood sugar level checking, and including a striking visual prayer for the injured Red Cadeaux along with a lament for the many race horses who die or are killed prematurely. Alrey Batol's lightly interactive Clearance amusingly mocks the accumulation of everyday goods from phones to espresso machines in the form of a calculatedly irritating computer game. A more disturbing delirium is induced by Joe Hamilton’s beautiful indirect.flights with its mobile collaging of surfaces natural and synthetic, thick paint, Google Maps and snippets of equally hard to place functional sounds.

Peter Wildman’s code poetry is quietly multi-voiced over images of open mouths in which appear fragments of code and text with some witty outcomes within an overarching sense of delicate reflection on life and love. To enjoy Josh Harle and Louise Zhang’s fascinating interactive sensory blend of animation and sculpture, Blobs, you’ll need to spend $0.99 for the app. A panel of six performances on video by vocal noise artist Kusum Nomoyle are activated by hovering the cursor over an image and clicking (it’s no good trying to hit Play or Pause) which also introduces degrees of colourisation into the industrial landscape in which the artist vigorously performs. There are more works to embrace—and without the stiff backs that ‘real’ galleries so often induce.

Roslyn Helper brings to the task experience in curating exhibitions and events for ISEA (2013), This in Not Art (2013), Vivid Ideas (2014) and the Brisbane Powerhouse (2015). She is the current Artistic Director of Electrofringe.

Helper’s interest in the effects of new technologies on society, culture and politics is reflected in her degrees: BA (Media Communications), University of Sydney and MA in Arts Politics from Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. An Australian online gallery focused on the themes that preoccupy her is an important innovation.

Interview

How did the New Physics come about and how do you envisage it?

It came about as an independent, self-funded project, the first iteration of a series of curatorial experiments presenting online art.

I'm not thinking of it as an online representation of a traditional gallery, but rather a new type of gallery: an entry + exit point / a distribution channel—a platform that caters appropriately to the artforms it presents. A URL can travel, relocate and decontextualise itself in the way that a room cannot.

The other thing to note with curating New Physics is that my approach inverts the traditional curatorial processes. Usually you start with a physical space and fit the artworks into it. In this instance, I found/commissioned the artworks first, and then designed a space around them.

What kind of work attracts you?

I'm not interested in a particular ‘style’ of online art. I think the beauty of the internet is that it presents such a plurality of perspectives. Rather, I'm attracted to art with a critical or conceptually rigorous underpinning: these works all play with familiar social, political and economic functions to examine and challenge the ways we think about and approach the ubiquitous online experience.

What kind of works will you curate and exhibit?

A combination of extant, reworked and commissioned pieces to create a more sophisticated art experience that properly caters to the net environment. A variety of online media have been chosen: website, game, app, instagram, video etc.

Internet culture has no aesthetic cohesion or unifying politic. Rather, the selected works present a diversity/plurality of perspectives that utilise, represent, satirise and disrupt online systems.

The New Physics catalogue essay illustrates the socio-political context that situates the exhibition and describes more fully the concepts behind each artwork.

http://www.newphysics.net

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. web only

© RT ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

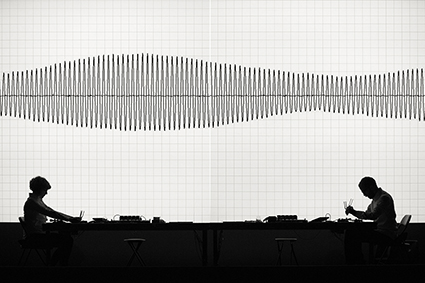

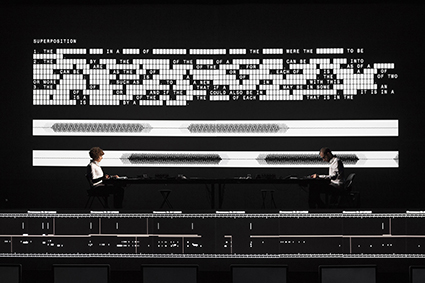

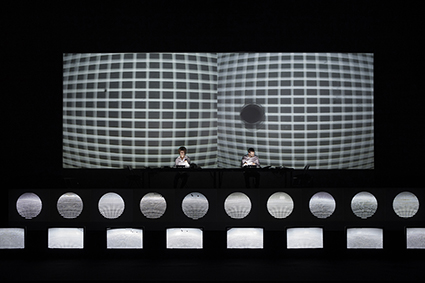

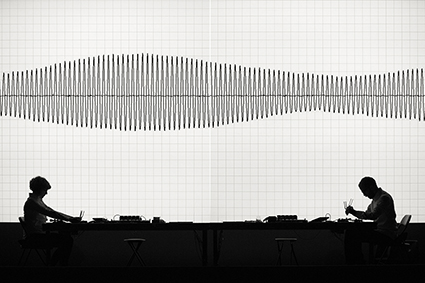

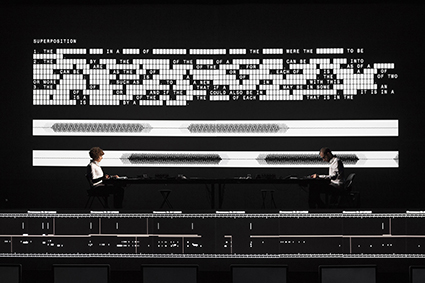

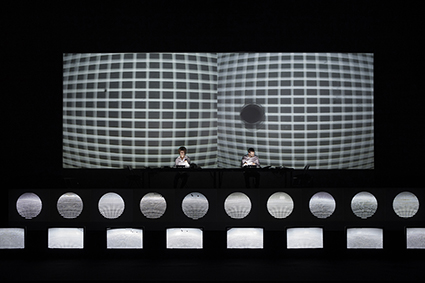

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

Image Zan Wimberley

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

It is film history legend that the release of Star Wars (1977, now known as Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope) changed the course of cinema sound. Director George Lucas and his gun sound design team used the just-emerged technology of Dolby Stereo Sound to hide a series of low frequency waves that accompanied the Star Destroyer and the Death Star at a pitch that the human ear could not detect but that the body could feel. As the monster spaceships passed across the top of the screen, the bass frequency produced a rumble that gently but tangibly shook the plush cinema seats and rang through the viewers’ bodies. It was a Freudishly evil move. The force literally inhabited people: the work was felt in the body rather than understood with the intellect.

I couldn’t help but think of this while experiencing Japanese artist Ryoji Ikeda’s newest work, Superposition, at Sydney’s Carriageworks. A similarly advanced space-time force invaded those who ventured into this vastly imaginative and precisely realised video, sound and installation work, currently touring the world like a music gig. An artwork about data sounds dry, but Ikeda has created another work of extreme coolness and affective power.

Unlike Spectra—the sculptural tower of white light that punctured Hobart’s skies in 2013—Superposition is the first Ikeda work I’ve experienced that occupies a traditional theatrical set-up. Rather than being plunged into a big space to move through, we face a series of onstage screens from the comfort of seats. It’s also the first work of Ikeda’s that includes performers: a hyper-focused woman and man reading streams of data and inputting them to the work in real time. Not only does their presence bring the work into the realm of time-based performance, it gives us a human element and a start-point to relate to in the data stream.

For an hour, the duo taps out messages through an array of Morse Code machines, tuning forks and microfiche scanners, all of which are monitored by Go-Pros fixed to the stage and beaming live onscreen. In this way, the work quite literally realises the 21st century experience of information overload, a return from cliché to truth. Each new data source has a corresponding effect: every movement by a performer produces a sound and image. In this way, Ikeda’s work reminded me of a basic law of physics—that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. This returns us to the work’s self-professed mandate of reflecting on how “we understand the reality of nature on an atomic scale…inspired by the mathematical notions of quantum mechanics.”

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

Image Zan Wimberley

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

Being conceived at the art-science nexus, Superposition also involves a crack team of offstage specialists involved in programming, graphics, computer systems and optical devices. Every little bit of the work–every little bit—is so fully realised, even the musical output could stand alone as a soundtrack, and was in fact separately commissioned by the Festival d’Automne in Paris.

But thankfully, Ikeda is smart enough not to prize the parts over the whole. There is too much to take in, but I suspect that is his intent: to drive us back to the realm of experience rather than analysis. He has developed a type of deeply conceptual art that embraces rather than rejects the aesthetic. While Superposition is mostly anchored in a Matrix-like monochrome palette, the artist understands the potency of an occasional thunderbolt of colour. Where beauty and sublimity have been central concerns of art since forever, Ikeda immerses us in a digital sublime of ones and zeros, bridging the massive with the minute.

Under Lisa Havilah’s directorship, Carriageworks continues to program works of the moment that have wide appeal. Audiences come to an understanding of a work through many factors: personal history, ideology, taste, other works, formal education and instruction in how to read an artwork. The scope of Superposition is so far-reaching that every viewer can craft their own set of associations in endless ribbons of interpretation. Given the movie theatre set-up, the work spoke to me cinematically, and as it devolved into something more abstract, I felt hurled into the final strobing third of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the trippiest part in which astronaut Dave is hurtled through space and time towards the star child and his own old-age.

But Ikeda’s creations are so much more than visual and aural representations of data dreams and physics and quantum mechanics. His are works to be soaked in and soaked up: truly immersive and experiential, even within the walls of a traditional stage space. In an age where much conceptual art must be clinically understood—dissected rather than felt—Ryoji Ikeda brings us back to the realm of affect and dreaming.

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

Image Zan Wimberley

Ryoji Ikeda, superposition, 2015, Carriageworks, Sydney

Ryoji Ikeda, Superposition, Carriageworks, Sydney, Sept 23-26

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 29

© Lauren Carroll Harris; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stelarc and audience, keynote for NEAF

photo Daniel Grant

Stelarc and audience, keynote for NEAF

The idea of experimental arts is evident in the branding of national bodies. The Australia Council for the Arts now has an Emerging and Experimental funding category, replacing its Inter-Arts Office. UNSW Art & Design (formerly the College of Fine Arts) incorporates the National Institute of Experimental Arts (NIEA). The Experimental Art Foundation has become the Australian Experimental Art Foundation (AEAF). Experimental arts have gone national, but what does experimental actually mean?

A series of discussions at the National Experimental Arts Forum (NEAF) in Perth sought clarity. They were shadowed by two conundrums: first, how best to articulate the value of experimental arts amid the recent threat to Australia Council funding; second, the relationship between experimental art and science.

This second conundrum came from NEAF’s host, the art laboratory SymbioticA, which had just held an international conference on Neo-Life and organised several exhibitions foregrounding collaborations between artists and scientists. Amid the sessions, an ongoing debate between Vicki Sowry of the Australian Network for Art and Technology and SymbioticA’s Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr revolved around the autonomy of artists in collaborative situations.

Zurr is concerned about the extent to which artists are being used to illustrate science and industry, the way that artists are employed for data visualisation and sonification projects. For her, a key difference between art and science is that art should be allowed to fail, rather than celebrate scientific success.

The value of failure, of process and experimentation, found another advocate in Australia’s savant of experimental art, NIEA’s Paul Thomas. In Thomas’ session on education, dLux MediaArts director Tara Morelos suggested that experimental art “makes strange with the technology, to force it where it does not belong.” Thomas then asked the group to conceptually disentangle arts made with technology and media from experimental arts, in the process illuminating some of the slipperiness of these terms.

Another angle on the problem came from Canadian academic Chris Salter, who in a concluding talk pointed out the similar histories of experimental art and experimental science. Both artists and scientists are expected to produce results of one kind or another that may or may not have anything to do with what actually takes place in their messy studios and laboratories.

Salter, Thomas and Zurr all work in universities that define themselves by experimental research, and are in something of a protected situation when it comes to making art. Many of the attendees, however, spoke about being stuck in funding cycles that shift from project to project, requiring outcomes rather than open-ended processes. These discussions had a depressing edge as participants tried to articulate what they did in terms of more concrete social and institutional values.

The recent threats to federal funding show how experimental artists need new and better arguments for their practices, and the conference rehearsed several of these. In an interactive keynote, performance outfit PVI asked whether art and politics should be distinct. Only Stelarc stood to agree with the proposition! His example may well stand as Australia’s best ontological argument for experimental art.

A video of Stelarc in the DeMonstrable exhibition at the Lawrence Wilson Gallery, called PROPEL-Ear on Arm Performance (2015) shows his body being swung around on a robotic arm, jerked from position to position. This robot body has all of the profound qualities of the artist’s more famous works, its audaciousness making a simple, sensual argument for its own intrinsic brilliance.

PVI suggested another reasoning for experimental art through a Frank Zappa video. 99% of NEAP attendees agreed with Zappa that “progress is not possible without deviation.” This is what Chris Salter calls a logic of innovation, as if artists will come up with new ideas and new knowledge purely by being different. This is something of a self-defeating argument, as instrumental inventions may or may not come out of an artist’s studio.

Even more troubling was a session in which artists complained about their marginalisation from the Australian mainstream, but at the same time defining experimental art as that which is marginal! Surely, this logic will only keep experimental artists at the margin!

Stronger arguments were made in other sessions. Darwin Community Art’s Christian Ramilo reminded everyone of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that says everyone has a right to the “enjoyment of the arts.” For Ramilo, the recent threats to the autonomy of arts funding undermine this right.

PVI Collective’s keynote/intervention, ‘quiet time,’ delegates trying to do nothing for 2 minutes

photo Daniel Grant

PVI Collective’s keynote/intervention, ‘quiet time,’ delegates trying to do nothing for 2 minutes

Sitting next to Ramilo, SymbioticA researcher Guy Ben-Ary described the speculative role of the artist who plays out the ethical implications of developments in the laboratory. As if to illuminate the point, Ben-Ary, on the night before NEAF, performed cellF, an improvised concert of cellular neurological networks jamming with a jazz drummer in Japan.

Despite the weighted and urgent nature of many discussions at NEAF, delegates came together for many highlights, notably three brilliant keynotes that took nothing for granted: an action packed performance lecture (PVI), a whisper quiet anti-performance lecture (Cat Hope) and a journey through bodies augmented, cellular and virtual (Stelarc).

So too in the many improvised discussions and fortuitous conversations, the serious atmosphere produced brutally honest and productive exchanges. Such is the vitality of what attendees were reluctantly calling a ‘sector,’ that like other sectors of Australian activity must learn to advocate for itself, to demonstrate its ontology in ways that everyone from the scientist to the voting public can understand.

As the field of science communication has been so successful in articulating the intrinsic interest of science and its social value, so the experimental arts need to be better at communicating themselves. We need an experimental art communication that brings the concepts of its practitioners onto a more public stage.

At NEAF in 2015, arguments and methodologies for experimental art were being tested among colleagues and friends. What remains is for these arguments and methodologies for experimental practice to make themselves more visible through punchy, quality art and its ideas.

SymbioticA, National Experimental Arts Forum, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 5-6 Oct

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 30

© Darren Jorgensen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

National Sawdust, New York

photo Jon Rose

National Sawdust, New York

Last month Jon Rose was invited to be one of the curators in launching New York’s new ‘new music’ space National Sawdust with his Interactive Sonic Ball project and to undertake a 12-concert residency at The Stone performing with John Zorn, Marc Ribot, Mark Dresser, Shelley Hirsch, Elliott Sharpe, John Medeski, Sylvie Courvoisier, Peter Evans, Cyro Baptista, Chuck Bettis, Ned Rothenberg, Ikue Mori, Okkyung Lee, Francesco Mela, Ches Smith, Miya Masaoka, David Watson, Eyal Moaz, Lucas Ligeti, Andrew Drury, Annie Gosfield, Olga Bell, and Anthony Pateras. His experience of National Sawdust and The Stone has inspired Rose to imagine a model for a sustainable music culture in Sydney against the odds of power and property values if without optimism about Australian arts philanthropy and state arts funding. Eds

The composer & the philanthropist

I’m the last one to suggest any arts practice in Australia copies, or tries to emulate, an overseas model; our recent history is littered with cringing attempts at that. But occasionally something pops up elsewhere that is extraordinary, and we would do well to examine what has taken place and see if it is relevant (or not) to our local predicament.

Paola Prestini is an Italian-born, award-winning composer who has just presented those in New York who are interested in new music with an ultimatum (she doesn’t put it like that, but I do). The message is simple: in a world where performed music has lost nearly all its value and function, if we want live new music, then those who can afford to need to put their philanthropic best foot forward—and now.

Kevin Dolon is a tax lawyer and amateur musician; he wanted to do something about the state of new music in New York. Kevin is not your usual New York megaphone conversationalist; he is quiet and thoughtful and makes his way around on bicycle. He found a building that was literally the ruined shell of the National Sawdust Company in Williamsburg and persuaded other well-resourced businessmen to put up $6 million. Paola Prestini raised $6 million to match it—a composer and musician did that! With a final cost of around $16 million, another 50 donors chipped in too. Total running costs are $2 million annually.

In the US, there is always a clear bottom line, and in a place like New York even performing in poverty is expensive; in this respect Sydney is fast achieving parity. National Sawdust has five years to make itself into a going concern: the rent is free, the sponsors own the building. If the whole enterprise falls over, the owners can sell the building for a fortune. Since it’s on prime real estate in New York they cannot lose, but in the meantime they can create something exciting, unique and worthwhile—something they are proud to attach their names to.

It has to be said Paola Prestini has no intention of failing at anything. Her talent is aligned with a practicality and a relentless determination; she is also a top composer. The vibe in the opening month of National Sawdust is one of excitement and of generating a brave new performance option in a cultural environment and malaise that is drifting or even speeding in the opposite direction. The music in the opening weeks was a hard core of genres from modernist chamber music to 1990s rock, from free improvisation to electronica, from small scale music theatre to solo mandolin or oud virtuosity, from maximalists (John Zorn) to minimalists (Terry Riley), and just about every style of singing under the sun. It was inclusive, and nothing had been watered down for ease of consumption.

The building itself is state of the art. The actual performance space sits on huge springs that insulate it from the noisy streets and nearby subway. This I am critical of, as I would prefer to play in a space or place with specific resonance, not avoid the uniqueness of given sonic characteristics. The ubiquitous black box performance spaces dotted around the world are mostly interchangeable. One night down at The Stone (where I was doing another residency) the neighbouring sound world took its place in the band: the road adjacent was being resurfaced by giant noise-wielding machines, and we were taken to the world of high decibel industrial music (clearly audible in the club) whether we liked it or not—we went with it.

Practicalities

The situation for National Sawdust requires another operational aesthetic; it’s sitting on very expensive and escalating real estate. Paola will have to hire the space out to just about any kind of commercially viable event that involves music if NS is to survive. She looks at me sternly and says, “We won’t do weddings.” So there is a line, a line I crossed many times in the days when I was a professional musician—I once even played a divorce party on a fat cat yacht on Sydney Harbour.

My first glance at National Sawdust brings amazement and a feeling that this is not built for the use of humble musicians but for the enjoyment of architects. However, from the point of view of Paola’s long-term plan, she needs a performance space that can also be a recording studio for an 80-piece orchestra playing Hollywood film scores or TV shows, bringing in the mega sums of loot that will keep this place going. The location is also significant with respect to demography. The restaurants and bars in the nearby streets are packed out with 25-35 year olds wielding trust funds—if you are up and partying at two o’clock in the morning on a Tuesday night, it’s unlikely you have a real job to go to at eight the next day. The National Sawdust needs and wants their money to make itself sustainable. The multi-purpose character of NS has it fitted out with one of the best sound systems that these ears have ever heard—a paradigm of sound reinforcement as opposed to amplification. The smallest grains of sand falling on a table…a cranked up DJ—I heard both extremes and everything in between in the main auditorium.

But Paola’s passion remains for the new and the experimental; there will be no fewer than 500 concerts a year. All her methodology, planning and process runs at hyper speeds with this one aim in mind—the popular supporting the less popular or even the unpopular (likely to be the most interesting). The bottom line always looming. The financial support she has made available to musicians such as myself also goes beyond the accepted terms of engagement and generosity—my residency at The Stone was in fact made possible by National Sawdust.

A model for Sydney?

In the 1970s I had a choice of over 15 free venues in Sydney that were amenable to new and experimental music (galleries mostly, but also some jazz and rock clubs). Crushed by land speculation and basic greed, this option for performed new music has pretty well collapsed. The best venue in town for improvised music is now a private house holding 50-90 persons; entrance is by donation (it would be illegal to charge an entrance fee), and it is not on social media. The punters are, in the main, generous—they know the tenuous state of affairs for musicians. The People’s Republic in Camperdown is already a model for the performance of music, but obviously you can’t put a PA and a rock band in there.

So, what other kind of model could work in Sydney? Clearly, the few philanthropists who support music are going to stick with handing over their loot to those who already have the bulk of government funding—ie the models of late 19th century opera, orchestras playing largely classical music, or the use of celebrities who might make Mozart look a bit hipper (although the more Australian classical musicians try to act groovy, the straighter they tend to look).

Scale and appropriate use of resources are two factors that need to be addressed. The aesthetics and grandiose power displays of European empire in the late 19th century surely have no place in the 21st century. The Sydney Opera House is a black hole into which money is poured with little significant cultural return. Can’t we just sell it off to the Chinese and use the cash to promote musical activities that have some use and benefit to society? (The façade of the SOH stays of course, generating the tourist dollars—job security!) It would be cheaper anyway to send those who can’t live without Puccini or Wagner on a package holiday to Milan or Bayreuth where they can catch the real thing, rather than indulge their expensive taxpayer-funded fantasy in Australia. The capacity of National Sawdust in New York is 175 seated and 320 standing. The Stone is legally limited to 75. These are appropriate-sized venues for a city characterized nowadays (as are the metropolises of Australia) by a plethora of niche musics.

Jeffrey Zeigler (cello) Andy Akiho (steel drum/ composer) & Roger Bonair-Agard (Beat poet), Opening Night, National Sawdust

photo Jon Rose

Jeffrey Zeigler (cello) Andy Akiho (steel drum/ composer) & Roger Bonair-Agard (Beat poet), Opening Night, National Sawdust

We have become such a controlled society that it is very hard to know where or how to operate as a musician and also quite challenging not to get depressed about the whole business. We all work for free, providing unimaginable amounts of wealth via our data to Google, Apple, Facebook, the government and the rest of them. Taking back control of our lives might be a start, but is that just too difficult?

At root cause, it comes down to the ownership of (once stolen) land. The Australian Opera says its tickets are under $100 a seat, but that is horse manure; the real costs of subsidising a building like the Opera House in Sydney’s bubbling real estate market are astronomical. If you want the proof, I suggest putting it on the market with plans to turn it into the usual apartments and restaurants (like “the toaster” next door)—it would be worth billions in seconds. Hey, why not add a casino as well?

Historically, non-classical music (what the Germans call Unterhaltungsmusik—music for entertainment) has been partnered with booze, drugs and, more recently, food. On the positive side, you could say the music was functional; on the negative, the music itself didn’t pay the bills—or enough for an entrepreneur to want to start up a club. John Zorn’s approach to The Stone club in New York City is reductive—no bar, no food, no drugs—just the music. The aesthetic shows off his puritanical side, but with audiences drawn from a population base of 20 million, it can work. It’s low-level street capitalism taking a small bite out of The Big Apple. There are other examples, but most come and go, run out of steam or money or get moved on. The Stone is still there after 10 years. To play at The Stone, you have to be invited by its owner—the club is booked for up to two years in advance—a two-year wait to play for the door! Every month there is a rent gig where Zorn’s own celebrity status ensures a full house. Despite the $25 entrance fee, I suspect the Doyen of Downtown music puts a lot of his money into the place as well.

You don’t have to wait two years to play in Sydney; there is not yet the population pressure, but give it a few years. Even if you do get to play in Sydney at a club or pub, the chances of earning an ‘adult wage’ without a subsidy are remote. Meanwhile, with the rationale of a third world dictatorship, extreme perversions of power are staged here. The previous Minister for Bullying putting his hand in the Australia Council till and walked off with 28% of it for his own slush fund in possibly the most blatant abuse of democracy ever to happen in the arts since federation—even New Yorkers are shocked by that! Similarly, the quarantining of the bulk of Australia Council funds for the benefit of a few reactionary institutions, which are never tested with any peer review, is a continuing profligacy—a casual insult by the powerful to the democratic process.

So, short of returning the favour and directly stealing from the rich and powerful, what’s to be done? To quote George Orwell, “In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act”; that could be a useful start but would be considered too hazardous by most musicians. Biting the hand that feeds you is a tasty but tough ask.

Can a society with a limited funded sector organise itself better than we currently seem capable of? This probe goes right to the heart of the way in which power is organised in Australia and the few who use it—and use it only for their advantage, to protect their privilege and status.

Just after returning from New York, I heard a philanthropist on Radio National promoting her new concert hall at the Ngeringa Cultural Centre near Adelaide. Great, I thought. Australia is on the move. But then after the listener’s hopes are raised comes the reality check—some 19th century notions that hardly seem possible in a 21st century modern state—”bringing culture to nature” (in other words, human exceptionalism is something that nature can’t do without; nature has to be improved by human intervention) and “the perfect acoustic” (in other words, Vivaldi in Venice). So, despite the best intentions of putting money into the arts, it’s the colonial mindset that continues to dominate in Australia.

The crowdfunding solution?

Ah, but what about the wonders of crowdfunding? There are but a handful of successes, and those are in the realm of pop music. Well, you might expect that, as popular music assumes the hierarchy of popularity rather than an innovative and flourishing musical culture. Even organisations with clout like The New York City Opera couldn’t do more than raise $301,000 of a targeted $1 million in their quest to avoid collapse. Random generosity is a rare quality in our species; the chances are that those who want to support an organisation are already familiar with it and probably handing over their pennies. Crowdfunding doesn’t appear to cut it.

Survival and sustainability

Anyone who dares predict the future is likely to end up with egg on his face. But I do believe performed music will survive, and I think it will thrive, especially as the myth and delusion of continual economic growth (on a planet with diminishing resources) evaporates. The scale will be small, personal, and community orientated (that’s a hard one for most of Sydney), and it will have to be supported by those lucky enough to own property or other resources and willing to share on a regular basis. It will come down to personal relationships and a desire to contribute. The performance of music has always mirrored the great heaves of economies, the ebb and flow of migration, the collapse of empires; there is no reason to think that our time is any different. The cultural paradigms of post-WW2 are not quite gone with a bang, but they are whimpering.

In the past few years, under the guidance of Lord Mayor Clover Moore (who posed the question—what the hell happened to all the live music and venues of her youth?) the City of Sydney has made attempts to reclaim its live music culture. This is a Herculean task, but there are some results (The Tempe Jets practice space for musicians being one example). I think an integrated holistic town plan that involves the practice of music along with bicycle lanes, urban greening, the installing of car-free pedestrian zones etc is certainly a key to any sustainable quality of life in a big town. And if the citizenry can persuade the “big end of town” that such a process benefits them as well, we will by default have more options for the practice of music. The only problem with this officially granted approach is that we may end up with the clean, saccharin culture of a Singapore. One integral aspect of live music performance has always been the temporary loss of control—the access to another reality.

In this country there are many small organisations doing a great job (NowNow, Make It Up Club, Sound Out, Tura, Sound Stream, Clocked Out, Ensemble Offspring, Speak Percussion, Decibel, BIFEM etc) but all are to some degree dependent on diminishing government funding. This exacerbates the precipitous state of affairs, even defining the kind of music that must be squeezed out of the communal funding bottle—the last drops of the 20th century model. Even the hugely versatile MONA FOMA, supported by the gambling largesse of David Walsh, is underwritten up to 50% by the Tasmanian taxpayer. Australian corporate wealth tends to end up offshore, and it is highly unlikely to ever enter the philanthropic world on the side of the local, the appropriate, and the challenging.

Interactive Sonic Ball project of Jon Rose at National Sawdust Community Day

photo Jill Steinberg

Interactive Sonic Ball project of Jon Rose at National Sawdust Community Day

In Sydney, millionaire Judith Neilson seems set to outspend Walsh with her new Phoenix gallery in Chippendale—there will be space for performance, but I cannot see new music being a priority. This is visual art: a world dominated by money and fashion where there is a toxic mix of dubious philanthropy and the use of taxpayer’s funding to support the visiting superstar of vacuity.

Maybe money is not the base problem or solution; perhaps it is one of time and commitment and a move away from the overpriced centres of our cities? Music was one of the first professions to be hollowed out by the digital revolution; to that extent, musicians are in the vanguard. There are no illusions, and the hardcore practitioners of new, improvised and experimental music have been writing the self-reliance manual since the advent of musician-run record companies and festivals in the 1970s. (The use of the word “experimental” is problematic, as words associated with creativity have been devoured and neutred by mainstream capitalism. If the Australian Chamber Orchestra professes to promote the “experimental”, you know the word is now meaningless. But I can’t think of a relevant replacement; “exploratory music” or “new music” have the same problems; this is why I used “other” in the title of this proposal.)

Australia will finally be a republic and have a non-colonial flag long before a group of millionaires come to the aid of “other” music as I witnessed in New York; we musicians will have to do it ourselves.

A proposal

My proposal is that Sydney develops its own network of say 10 musician/artist run spaces using The People’s Republic in Camperdown as a model. Despite an aging population, it is vital for the future of music performance that such a network be initiated by the young (and not established middle-aged musicians) and that the spaces (front rooms, garages etc) belong to them (or more likely their parents) and that they set the agenda. A monthly concert in a private space—it can’t be that hard, can it? If there were 10 such spaces (all distinctively different), that would provide 120 concerts a year, constituting an appropriate minimum-sized pool of musical creativity for a town such as Sydney. I did suggest such an idea to The City of Sydney when they were canvassing ideas for the rejuvenation of live music two years ago, but the terms of reference were limited to rock bands, singer-songwriters, and DJs—it’s as if most of the innovative music of the 20th century had gone missing or never happened.

In the 1980s and 90s, I lived in and helped run Die Küche (the Kitchen) in Berlin. There are many places currently in Berlin that follow a similar model. However Berlin remains cheap in comparison to Sydney, and the buildings are bigger—the war-torn history of Berlin still provides cheap unrenovated buildings suitable for live music (hurry, hurry, they are going fast). However, I think the problems of creating new music in a place like New York are more relevant to the contemporary over-priced bubble that is Sydney.

Creating a new reality

Meanwhile back in New York, Paola Prestini and John Zorn are both musicians who realised early in their careers that there are no free lunches, and if they were going to achieve their musical ambitions, they would have to be, by necessity, impresarios. Their visions are very different, but the cause of presenting challenging, live, contemporary music is mutual. Eventually it comes down to individuals sticking their heads up above the parapet of conformity and creating a vision and a reality where there was previously none.

Jon Rose, electric violin, Julia Reidy, electric guitar; plus The Great Fences of Australia multi-media event, Jon Rose, tenor violin The People’s Republic, Camperdown, Sydney, 6 Dec, 7pm; Jon Rose, Julia Reidy; plus book launch, Jon Rose, Rosenberg 3.0—not violin music; The Make It Up Club, Fitzroy, Melbourne, 8 Dec, 8pm

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. web only

© Jon Rose; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stephen Whittington & Daruma, Japan

Sounds were ‘born free, but everywhere they are in chains’ (Rousseau). Captured, held prisoners in hard drives, USB sticks, iPods, smart phones, they are forced to remain mute in the darkness of their digital cells, released for a short time, if at all, at the whim of those who believe they possess them, affording their would-be owners a moment’s distraction, a fleeting pleasure, a soundtrack to the movie of their lives, before being cast back into the gloom of the digital netherworld, abandoned, without hope. In their prison cells they are mere cyphers, their sonorous existence reduced to nothing more than data. We are the gaolers of this digital prison, we who created the infernal machines that capture ephemeral vibrations and enslave them. Our digital storage devices are Piranesi’s imaginary prisons; his nightmarish vision is the reality of sound today – sounds are oppressed by us, who imagine we are their masters. Yet we are more enslaved than they are, enslaved to our delusions of mastery over the sounds that we oppress. Only by renouncing our claim to possess sounds can we escape from our own enslavement.

Sounds were born free, and ‘to win freedom is their destiny’ (Busoni). But for them to realise their destiny, we must recognise that we cannot own sounds. At best, we are the guardians of sounds, and role is to protect them, not imprison them. The ‘music industry,’ the ‘entertainment industry,’ the ‘media’ and the ‘art market’ have turned sounds into commodities that can be traded. This commodification has warped our relationship with them. We imagine that sounds can be bought, sold and owned. The value attached to sounds is their use value; the more useful they are to us, the more highly valued they are. We can manipulate them, control them, make them serve us, to achieve whatever ends we seek. We use them to make people pay attention to us, to love or admire us, to express ourselves, to advance our careers, to achieve wealth and power, to dominate and oppress our fellow human beings. We do not consider what we can learn from sounds, only what we can do with them, how we can use them, how we can consume them, what they can do for us. The intrinsic nature of sounds themselves is forgotten.

But our relationship to sounds is of a different order; we are like strangers who meet on a journey, who experience nothing more than momentary eye contact, a flicker of acknowledgement of one another’s existence, before going our separate ways. That is why an encounter with a sound is so often accompanied by sadness, whatever pleasure it may also bring. Sounds move towards us, but they also move away, and remind us that whatever and whomever we encounter in life we must eventually say farewell to them, or they to us. The evanescence of sound is an essential part of its nature, and for humans that is its greatest value. Sound is perpetually in the state of vanishing, slipping away from our attempts to grasp hold of it, defying attempts to make it a ‘thing.’ The perception that sounds are things, and therefore able to be possessed, is reinforced by the use of the word ‘sound’; it would be preferable to adopt a term such as ‘sonorous being’ or ‘sonic becoming.’

Freedom and truth are inseparable. The true nature of things is only revealed when they are free to be themselves, and only when that occurs that can we experience their true nature ourselves. All forms of categorisation are barriers to truth and freedom. We may find categories such as music, sound art, sonic art, performance and conceptual art useful for our own purposes, but from the perspective of sounds these are further tools of oppression, barriers preventing them from revealing their true nature. Sounds are entirely indifferent to any categories that we put them in; we trample on their right to be themselves by forcing them into categories which inevitably constrain the way in which we listen to them. Is it not sufficient that we have now incarcerated sounds in our digital dungeons? Do we need to restrain them further in categorical straitjackets?

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/85/8501_Large_Ulam_VLF_Loop_(graphite),_Joyce_Hinterding,_image_courtesy_MCA.jpg" alt="Large Ulam VLF Loop (graphite), Joyce Hinterding (see RT 129).”>

Large Ulam VLF Loop (graphite), Joyce Hinterding (see RT 129).

image courtesy MCA

Large Ulam VLF Loop (graphite), Joyce Hinterding (see RT 129).

If sounds are to be free to ‘be themselves’ (John Cage), we have to surrender our illusion of mastery and learn to attend to them in a different way. The dominant current mode of listening is oppressive; it imposes use value, and egocentric gratification onto sounds. We must renounce our ownership of sounds and learn to listen – again, or perhaps for the first time. This means reaching a stage of listening in which we acknowledge that sounds have an existence that is independent of us and our desires. The act of listening begins with the acceptance that sounds have an intelligence of their own, and all that they ask of us is to become resonating bodies in which they can reveal themselves. We must accept the responsibility we have to liberate sounds by cultivating the act of listening; the responsibility of the arts is to assist us in that cultivation, which demands an approach to art that respects the right of sounds to freedom, and refuses to “push them around” (Morton Feldman). Instead of asking what we can ‘say’ with sounds, artists must ask what sounds want to say to us.

Everywhere we look—and listen—we find sounds that are oppressed by commodification, objectification and exploitation. It is a pitiable sight to see innocent and defenceless sonorous beings, which long ago in human history belonged to the realms of the magical and numinous, reduced to slavery, at the beck and call of capricious masters, ruthlessly exploited for egocentric and materialist ends.

Accordingly, we need a declaration of the rights of sounds. The underlying principles for this declaration are:

1. Sounds have the right to be free and to reveal themselves in the truth of their own nature

2. Sounds are not possessions, and cannot be owned, bought or sold

3. Sounds must not be controlled, manipulated, exploited or oppressed for the gratification of human desires

4. Sounds have no interest in art, and any art that oppresses sound for its own purposes is not worthy of the name

5. The liberation of sound requires the active cultivation by humans of non- oppressive modes of listening

Therefore I call upon all those who love sounds for their own sakes to join in the struggle for the liberation of sounds from their state of oppression, to fight for the rights of sounds to sound in freedom, peace and harmony, to end the exploitation of sounds for the basest of human motives, to learn to listen to sounds by becoming ourselves resonating bodies, and thus discover what sound has to teach us. Let us renounce for all time the delusory belief that we own sounds and can do with them whatever we like.

Once we have ended the enslavement of sounds, we will end our own. When sounds are free, we too may hope to be free.

Declaration of Sonic Rights, Stephen Whittington, on behalf of the Sonic Liberation Movement, first read at the Australian Experimental Arts Foundation’s Art on Tap, Adelaide, Oct 15, 2015

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. web only

© Stephen Whittington; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“New Physics is an online exhibition that presents ten Australian artists who produce a collective though diverse aesthetic investigation of the dislocative effects of the internet, and the many unlikely collisions it has created.” New Physics, Introduction, Roslyn Helper

“New Physics is an online exhibition that presents ten Australian artists who produce a collective though diverse aesthetic investigation of the dislocative effects of the internet, and the many unlikely collisions it has created.” New Physics, Introduction, Roslyn Helper