Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

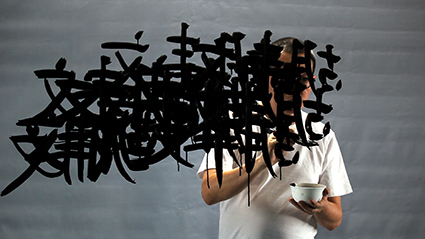

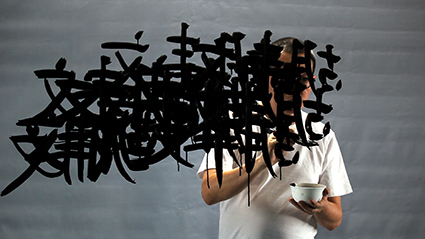

Ben Brooker takes you deep inside four works in the 2015 OzAsia Festival, the first under the direction of Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell whose focus on cross-genre and cross-cultural performance and transnational engagement was immediately evident. Audiences live out Indonesian street life with Indonesia’s Teater Garasi, grapple with an overwhelming flow of digital data in Ryoji Ikeda’s Superposition, ponder the metaphysics of the collaboration between Australia’s Dancenorth and Japan’s Batik in Spectra and, raincoated, are awash with water, tofu, seaweed and everyday junk in a “spectacle of self-eviscerating excess” in Miss Revolutionary Idol Berserker from Japan.

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015

–

Top image credit: The Streets, Teater Garasi, photo courtesy the artists and OzAsia 2015

Haunting, creative team led by Julie Montgarrett, On Common Ground, CAD Factory

photo Jason Richardson

Haunting, creative team led by Julie Montgarrett, On Common Ground, CAD Factory

Last year The Cad Factory, along with National Museum of Australia’s historian George Main and friends, took a three-day healing walk from the Narrandera Common on the Murrimbidgee to Birrego, 40km away. This year they returned to the Common with many more friends to install sculptures, textiles and other works. Dozens of artists and many more locals came together to promote different perspectives on the location, and the healing theme continued with acknowledgment of the river’s long history as a contested site.

This historical perspective was brought into focus during Haunting on the Friday and Saturday nights, featuring a collection of vignettes from the region with images projected onto the river redgums across from Second Beach. Richly saturated photographs streamed through smoke onto pale trunks and eroded banks, as Main and others provided recorded narration over an atmospheric soundtrack.

Haunting was developed by The CAD Factory’s artistic director Vic McEwan during his time as artist-in-residence at the National Museum of Australia. His projections brought together water, earth and branches and made them active in the storytelling, “enabling understanding that would be possible nowhere else, under no other circumstance,” said Main in his introduction to the event, quoting literary historian Robert Macfarlane’s view of the poetry of Edward Thomas.

Main remarked in his narration how few of us look at the fields of wheat in the Riverina and imagine the forest of redgums that existed before the latter half of the 19th century. The Common is one of those places where a stand of Australian gums feels like a forest. Many old trunks are wider than cars and some have scars from Indigenous use. While the trees reflect an older landscape, the projection of static images from old photographs panning slowly across the river did too. I thought of the early days of Australian cinema, when the Limelight Department of the Salvation Army was one of the world’s first film studios.

The idea that art is spirituality in drag makes a lot of sense at a Cad Factory production, as the audience see local stories projected large. However, a reverential tone and too much spaciousness for reflection can feel ponderous. The snippets of history were like bubbles on the passing river and the variety of voices helped but sometimes Main spoke so…very…slowly.

It was surprising to see police arrive as the audience departed Haunting. A Facebook message from Michael Petchkovsky later described an incident with a local: “The lout [one of ‘the boys’] must have thought the bunyips had come for him when Hero Fukutu and I floated Gay Campbell’s gorgeous black swan right past him in the darkness and Craig said ‘boo’ to him from behind. He leaped up and ran screaming from the beach in front of all his friends, giving us all (his mates included) the giggles…”

The next day a local artist told me these ‘boys’ were a feature at local events. Perhaps they are performance artists in their own right? She also enthused that the youthful audience weren’t engaged in their usual activities on the Common, reinforcing the notion that this landscape remains a contentious space.

On the Saturday night there were introductions from Vic McEwan, George Main and local artist Michael Lyons, who performed imitations of wildlife such as “devil birds” (owls) on didgeridoo. It was the first of two musical performances that bookended the night. Local musician Fiona Caldravic closed Haunting with an operatic vocal in a bewitching outfit. It wasn’t until I looked at photos that I noticed the pattern on her cloak matched the huge backdrop—Vanishing Point, an installation across the river that was colourfully lit but still impressive the following day. Narrowing wires elegantly formed a vanishing point and billowing fabric served to reflect the black swans that had been driven from this landscape. The team of artists led by Julie Montgarrett drew on the writing of Mary Gilmour who attributed the decline of the swans to “swan hoppers” [whose work was to hop the swans off the nests in the breeding-season and smash their eggs, disrupting their breeding in order to reduce the birds’ damage to pasture. Eds].

Swans and billowing fabric were recurring features in On Common Ground. Black swans appeared at First and Second beaches in the works of Kerri Weymouth, on a totem pole, and Julie Briggs, in a formation of paper birds streaming down the riverbank. The title of the latter, Yes Faux Nature is a Real Trend, is explained in the program as referencing Glen Albrecht’s term ‘solastalgia’ to describe anxiety in response to negative environmental change.

Tangible Spirit (detail), Emma Burden Piltz, On Common Ground, CAD Factory

photo Jason Richardson

Tangible Spirit (detail), Emma Burden Piltz, On Common Ground, CAD Factory

Fabric on site took many forms, including kites, quilts and an extensive variety of eco-dyed sheets that were the result of workshops with local artists and Nicole Barakat earlier this year. There were many shades but also beautiful details, such as printing the shapes of leaves and branches.

Emma Burden-Piltz is one local artist whose practice has blossomed through collaboration with The Cad Factory. When I interviewed the artist for Western River Arts she identified circular motifs as an element from the landscape incorporated into her collections of found and reworked objects. In Tangible Spirit, Burden-Piltz hung eco-dyed fabrics to give form to the movement of air, as well as shaping structures that resembled fishing traps. Up close I spotted hand-sewn circles.

Another local artist, Elizabeth Gay Campbell, creates often seemingly simple sculptural figures with a deeper message. Ophelia (2015) shows the character from Hamlet dying in a puddle surrounded by rubbish. In the program the work is described as acknowledging contaminated waterways and bush—the dying Ophelia the only remaining beauty, but she’ll too soon decay.

While a number of the works in On Common Ground expressed pessimism about environmental change, the event was beaut for its appreciation of Narrandera’s magical Common. Vic McEwan often explains CAD Factory’s role as creating memories within landscapes. This collection of activities and installations revealed On Common Ground to be much more than Bondi’s Sculpture by the Sea replicated on the Murrumbidgee.

The Cad Factory, On Common Ground, artistic director Vic McEwan, creative producer Sarah McEwan, project co-ordinator Julie Briggs; Narrandera, 16-18 Oct

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 32

© Jason Richardson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

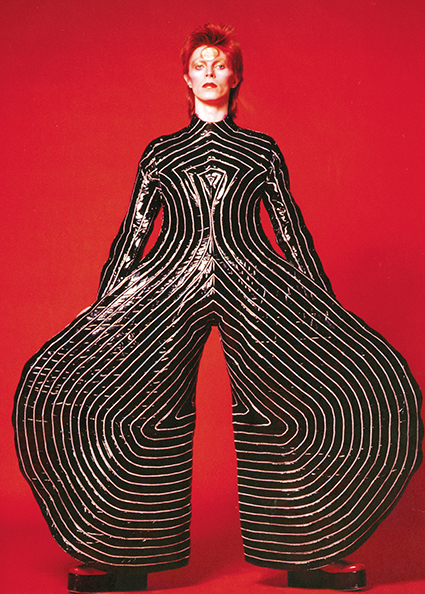

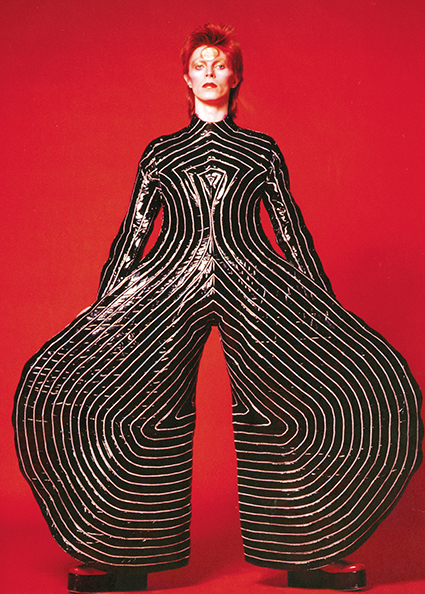

Striped bodysuit for ‘Aladdin Sane’ tour, 1973. Design by Kansai Yamamoto.

photo by Masayoshi Sukita

Striped bodysuit for ‘Aladdin Sane’ tour, 1973. Design by Kansai Yamamoto.

Babies, drunks and grandpas all know that David Bowie flirted with the image of sex, toyed with the image of avant-gardism and flaunted the image of mask-making. And sloths, slugs and doorknobs know that the promotion of imagery within music has remained a contentious issue ever since 18th century aesthetes worked hard to ingrain the Neo-Classical ideal that each art form should be pure unto itself and seek to attain its own ontological plateau of perfection. The 2013 Victoria & Albert Museum touring exhibition assembled from David Bowie’s Archive—pretentiously titled David Bowie Is—presents its findings as if Bowie invented the cultural brazing of sound and vision.

The exhibition charts how Bowie intuitively cross-hatched theatrical bricolage with persona politics and continued to ‘revolutionise’ mediarised music production across four decades. Maybe he did. But Bowie—the slut of the sonic, the tart of the textual—ripped into popular music by ripping off the late 60s vintage mania of second-hand clothing emporium styles which bloomed from Haight-Ashbury to Carnaby Street. Well before the cut-ups of Gautier/Goude, Westwood/McLaren and Bowie/Burretti, you had Jimi Hendrix looking like an Afrocentric culture-clash torn from a Napoleonic oil painting; Janis Joplin looking like a Texan bar maiden mashed up with a desert-distressed Art Nouveau poster for Absinthe. Bowie levered himself from the gauche posturing of 60s transhistorical image-mining wherein heroic rock icons were self-constructed by looking as much into their mirrors as at their audience.

You wouldn’t know this from surveying the mothballing multi-media catwalk of David Bowie Is. The through-line has been so thoroughly self-determined that most visitors feel happy to be corralled by the fawning narrative and its eponymous creator’s prescience. But let’s scrutinise this thin white historical thread between Bowie’s imagineered past and our mediarised present: I for one think Bowie should be prosecuted if his flagrant manipulation of ‘image’ begat the likes of Björk, Beck, Lady Gaga, Bonnie Prince Billy, Amy Winehouse, Marilyn Manson, Lana Del Rey and Nick Cave. Counter to their salacious embrace of artifice, the arch meaningfulness of those artists synchs more to Bowie’s dilettantish works than to his sporadic inspired works. Yes, it’s great to still be stung by the spine-tingling inappropriateness and halted eroticism of the alien visages of Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Thomas Jerome Newton et al, but there’d been a far greater proportion of pale zeitgeist surfing in Bowie’s career.

As a teen fan of a near ridiculously high order, I have long noted Bowie’s contorted flips between crazed insight and embarrassing output. Standing in the rain eight rows back from the front at the infamous MCG concert of 1979 in Melbourne, I distinctly remember thinking by the third song that everything about the event was unexciting and weirdly insignificant—from his lame fisherman’s pants to the rank arrangements circa Stage (1978) to a god awful PA system only a footballer would appreciate. More, I was struck by the yawning gulf between Bowie’s ‘sound and vision’ and the ugly reality of how it was broadcast, staged, reported, rendered and transmitted. This was reverse Warholian logic, wherein Bowie’s audiovision—the image of music he fabricated and the melange of sonic styles he orchestrated—fully lived up to the empty stylishness of his gestural actions. Warhol transformed the abject banal into hyper art; Bowie often reversed the flow.

David Bowie Is notably gained access to the David Bowie Archive, but it feels like the V&A marketing department has shaped the exhibition more than its curators. What we get is: (i) a belaboured audio narrative forging a didactic trail; (ii) an over-designed theatrical presentation of artefacts; and (iii) a cynical and superfluous bombardment of TV screens. Yes, I get it: Bowie is image. Yet while the exhibition presents an amazing array of original costumes (those by Burretti and Yamamoto are stunning), it tarts them up as ‘image’ rather than ‘object.’ Some are stashed six metres up behind faux-telescreen grating and flashing ‘concert’ lights. Meanwhile, the exhibition’s hefty catalogue contains sumptuous pristine photos of all the key costumes on display; the book makes them look more actual than the exhibition.

David Bowie Is critically ignores the chance to materialise the fabric of Bowie’s key transformative stage personae, and to give physical museographic presence to Bowie’s costumery which has become so dematerialised, photocopied and hyper-imaged as to become nullified and tokenistic. While the exhibition adopts the uniquely British rhetoric of The Independent Group who inaugurated pop-as-culture in post-war Britain back in 1956 with their ground-breaking exhibition of Pop Art, This Is Tomorrow, it falls into the 19th century pit of artist-as-myth. Treating Bowie this way now does no service to anyone but bourgeois journalists and media teachers.

Bowie thought he was channelling Warhol, Burroughs, Dali, Duchamp, Schiele and Wilde, but he came nowhere near them in terms of concept, execution and innovation. David Bowie Is believes he was all those figures combined—without admitting to the delusional drug-laced phantasms conjured by Bowie between 1971 and 1978, which historically and culturally frame his brethren. The exhibition might have taken a leaf from Mick Rock’s iconic photos in the revealing hardback tome Moonage Daydream (2002). His stupendous archive proves that the amazing polysexual trans-alien pseudomorphic looks of Bowie start with the Haddon Hall red spiky cut of 1971 and peak with that look’s gaudy atrophy by the time of the Diamond Dogs publicity shots of 1974.

More importantly, the Moonage Daydream images are trailed by a ruminating text by Bowie, who was recorded looking through Mick Rock’s archive. His casual reminiscences were transcribed and edited into a running commentary. It’s a weird text: an oral account of Bowie looking into the mirrors of his past. (Numerous times this text is footnoted in the exhibition catalogue.) Yet not once does Bowie provide any interesting critical context for his self images: quite the opposite, he seems gripped by Wildean self-loathing. David Bowie Is silences that flippant voice, and instead broadcasts a hagiographic construction of Bowie on par with his own messianic concoctions.

Back in 2002 when Moonage Daydream was released, Glam Rock was derided, not lauded. Bowie’s mind was elsewhere: in 1998, he had launched BowieNet. A subscription-based fan-exploiting start-up venture, it was far more embarrassing than Glam’s glitter, with Kai Power Tools and insipid information-commodity-speak peppering its copy. It came one year after the outrageous stunt wrought by ‘rock and roll investment broker’ David Pullman who in 1997 marketed Bowie celebrity bonds, by securitising an artist’s royalties to enable said artist to self-fund future projects across the forthcoming decade.

David Bowie Is markets itself as if everything is grounded in the Ziggy/Aladdin/Diamond era Mick Rock fortuitously documented, but attempts to stretch that innovative sound and vision too far. Ultimately, the exhibition is a museographic version of the now defunct Bowie Bonds. As such, it sits well in the new millennial climate of atomised rock and pop culture. From Target launching Keanan Duffty’s bland range of post-Glam Bowie-inspired clothes (2007) to the Aladdin Sane face gracing a Brixton 10 Pound note (2011; a legal community currency), David Bowie really is all that too.

–

David Bowie Is. ACMI, Melbourne, 16 July-1 Nov

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 28

© Philip Brophy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

U.F.O. (Unidentified Female Object), Rakini Devi; costume Evangelos Laios and Jason Patten, Siteworks 2015, Bundanon

photo Heidrun Löhr

U.F.O. (Unidentified Female Object), Rakini Devi; costume Evangelos Laios and Jason Patten, Siteworks 2015, Bundanon

Arthur and Yvonne Boyd’s Bundanon property was gifted to the Australian public in 1993 as a centre for education and to support creative arts practice. Their bequest also insisted on public access to the site. Arthur Boyd obsessively painted this landscape and its anima mundi—or rather, his particular struggle with and against it. Many of his works examine the ‘guilt’ of an artist’s relationship to looking at and representing the natural world with an outside eye:

“Although I do the painting, everyone else who then looks at it is in the same position as myself. I hopefully have helped them to face their guilt also” (quoted in Grazia Gunn, Arthur Boyd, Seven Persistent Images, 1985).

This is especially evident in Boyd’s Nebuchadnezzar suite, which illustrates the fate and anguish of the King of sixth century BC Babylon who was banished for usurping a will and order higher than his own.

It is apt that Siteworks 2015 invited representatives of landcare, feral animal management, sociologists, philosophers, artists and architects to examine “The Feral Amongst Us”—an investigation of whether and how we humans place ourselves above or outside of the ‘wild.’

As recently as 2008, works proposed for Bundanon residencies that engaged with the site were not encouraged. Since 2011, Siteworks has perhaps overturned this tendency, but my ‘perhaps’ points to a caution around how we presume we relate to our environments. Is there actual dialogue between our bodily fluids and the rivers, our bones and the soil formed over our lifetimes and beyond? Is it too easy to transport cultural myths or practices from different landscapes (as did Boyd; as does Butoh) to help understand a landscape’s meaning and dreaming?

It is a boggy, wet drive over Clyde Mountain from Canberra in late September towards Bundanon. The sun peels the sky open at odd hours. It strikes me that most open-air events hope for clear skies. Indeed, a few of the Siteworks performances are cancelled. The four-hour talk-fest chaired by Robyn Archer is however untouched by the rain. The Glenn Murcutt-designed building has a flexible glass wall which opens to the river, but we sit facing the interior wall and a plinth for the panellists. This has the unfortunate effect of drawing focus onto the pull of human personalities over any sensed dialogue with the environment.

Alternately I feel punched, conversed with or lectured to. I suspect I sit in an audience nodding agreement with speakers who replicate their own views. Diego Bonetto chastises us for not understanding our edible weeds, Jennifer Atchison for not thinking with our environment, Adrian Franklin for farmers not listening to the evidence provided by science. Alarmingly, several panellists do not even listen to each other, absenting themselves from the room at particular times over the afternoon.

Architect Richard Goodwin gives a sweeping critique of his own profession, citing modernism and the anthropocentric ‘hero=architect’ as ‘dead,’ arguing instead for a practice which engages with social awareness (‘contingency’), minimal intervention, recycling of materials and a kind of ‘porosity’ or ‘irresolution’ which remains attractively vague against the harder-edged arguments of the afternoon.

Dean Bagnall, a feral animal management contractor from the local Shoalhaven area, modestly asserts the validity of culling feral animals to protect crops and farm animals. His talk sits in stark contrast with the later speaker Dr Fiona Probyn-Rapsey who delivers a hard-core lecture on the importance of letting creatures live in and for themselves. She cites Derrida for weight and authority. There is weight to her argument sans Derrida, but there is weight too in Bagnall’s argument, which is never picked up in the afternoon. Indigenous custodian Clarence Slockee plays the wise fool, nudging us towards a remembrance of Aboriginal relationship to land, but also claiming the infallibility of his peoples’ animal and landcare practices which makes my hackles rise.

Tim Low identifies our collective fear of death as blinding us to process and rational thinking through of human/nature/animal relationships. We eat, and are eaten, he asserts. He cites Val Plumwood, feminist ecologist and hero to many, who survived the ‘death–roll’ of a crocodile, and against which she held no grudges. Low, however does not mention that Plumwood not only felt the crocodile had a right to eat her, but that she herself sensed she transgressed by going upstream to where she was attacked. She had a sixth sense telling her she should not be there. Indeed, what is sorely missing from the forum is any discussion of the sensory intelligences—other than ‘sight’—that feed other ways of knowing and relating in the environments to which we belong.

Thankfully these aspects are grasped by the artworks installed for the day or performed from the onset of dusk. The site’s specific history, and Boyd’s contemporary dreaming of it, are most evident in Nigel Helyer’s exquisite Biopods—a rocket-ship, a boat—which physically reshape and recondition our listening. Each Pod is a vessel suggesting aspiration as well as the limits of form. Snippets of a seductively beautiful poem are triggered by human action: “The king’s heart is a stream of water in the hand of the Lord” (Proverbs 21:1).

Rosalind Crisp’s dance in the beam of a ute’s headlights is an exploration of disintegration, but her spoken text is impossible to hear. Open-air work always carries risk of interference, and there is meaning in the unexpected rubbings and gratings that occur beyond our control.

Elsewhere, Bonetto’s installation signposting edible weeds has already pointed us to things we value or devalue and ignore. On a “severe slope,” Branch Nebula puts a viewfinder on “things that bite” in a dance piece on the theme of wild things that watch, scatter, scarper, slide and are traumatised by human intervention. You couldn’t miss Amanda Parer’s inflatable, oversized rabbits which came to full beauty when lit at night.

But I almost miss a seminal image in Rakini Devi’s performance, because I am seated in the wrong position. But then, isn’t that the point? You see according to your [dis]position. Devi’s U.F.O. [Unidentified Female Object] begins in a puff of smoke—like the breath of a dragon, the backfire of a shot—and she appears like an enormous wayang puppet in full garb, picking her way like a giant cicada along a cat walk. A single beam of light casts the shadow of an enormous rabbit behind her. The joke’s on all of us: the ritualised beauty, the ‘exotic other’ rabbit becomes an overblown cartoon.

Speaking of entities in wrong places, Alan Schacher with NIDA Staging students creates “errant structures”—an outhouse, a heap and a bush shelter—that spit, shudder and try to crawl away, whilst Zender Bender salvage white goods and add sound and light to create a ‘bush doof’ that also comments on consumer throw-aways.

Branch Nebula repeat their epic Whelping Box from 2012, this time as a film recreated in the bush, which heightens the sense of men ‘whelped’ in endurance rituals that earn them a place in the tribe. The film is an epic comment on false heroism, compliance and suffering of the feral and human combined.

SITEWORKS 2015: The Feral Amongst Us, curator John Baylis, The Bundanon Trust, Riversdale, NSW, 25 Sept

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 31

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lehte II

photo Jude Walton

Lehte II

Jude Walton’s Lehte II could well have been created in the mid-20th century. Its clean, clear, sleek distillation of time and space into a fine dance work draws on many of art modernism’s principles, most notably its sense of abstraction, which underlies the very construction of this work. Lehte’s manner of abstraction consists of a series of operations that transform the dimensions of a performance space into an artwork consisting of sound and movement.

Lehte II was performed at Heide Museum of Modern Art, in suburban Heidelberg, in the former house of art philanthropists John and Sunday Reed. Designed in 1964, by architect David McGlashan, Heide II is a sandstone building with high ceilings, exposed brick and plenty of light. The house was built with a view to its becoming an art museum. It doesn’t feel like a home.

We are invited to sample the space, to inspect its glass cabinets, which house a mixture of historical objects belonging to the Reeds, exhibits from Walton’s earlier work on dance and books and a floor plan of the house with some algorithmic calculations, which formed the basis of the work. We look out the window. A woman adorned in a striking top made of blood red felt traces a pathway.

Passing through the rooms, we descend a staircase into an extremely tall room which houses a grand piano and features a high wall of glass framing the surrounding native garden. Two women enter a mezzanine high above. They lean out, turn and walk, tipping over like modernist ducks. A woman (Fiona Bryant) enters downstairs where we are seated. She skirts the wall, drawing attention to its material surface, eking out its dimensions. Her movement conforms to the room’s coordinates, especially its long shelving underneath which she curls. More women join in: walking straight ahead, turning corners, walking, turning, walking, turning.

A 90-degree turn has two points of reference: the body (an internal space) and the (external) space of the room. If the turn is produced by the body, in the rotation of the femur in the hip joint, the orientation of the torso and the spiral of the head, its clarity is felt elsewhere, between the internal space of the body and the room. We see the dancers draw on their somatic perceptions in order to calibrate their movement.

Meantime, and throughout, Kym Dillon constructs a series of sonic atmospheres, clear and resonant. The series moves forward without circling back. It feels… measured.

While the dancing mirrors the sparse purity that informs the modernist architecture of the house, it draws on a thoroughly postmodern sensibility in order to do so: involvement of the dancer in task-based actions, a submerged sense of self, no expressive or individualistic gestures, clean lines and ordinary movement. The clearest physicalisation of these tasks comes from those who are able to distill their skills into very plain movement, without any kind of mannerism. It is the plainness that sings. The music also. Formed from an occult algorithm that transforms the spatial dimensions of the various rooms into selections of white and black keys on the piano, the music is surprisingly melodic, an indication of Kym Dillon’s virtuosic engagement with the productive constraints of the piece.

Overall, Lehte II is a contemplative work. Its spaciousness allows the viewer’s attention to wander, over the sandstone walls, into the garden, forming sensory trails in the midst of thought. It is a very considered work.

Lehte II, made by Jude Walton in collaboration with performers Phoebe Robinson, Fiona Bryant, Sally Grage-Moore, Michaela Pegum, music Kym Dillon; Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 16-18 Oct

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 33

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

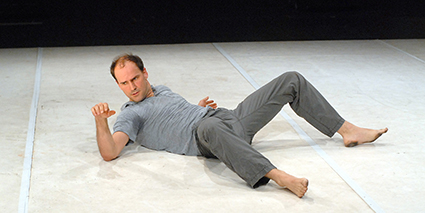

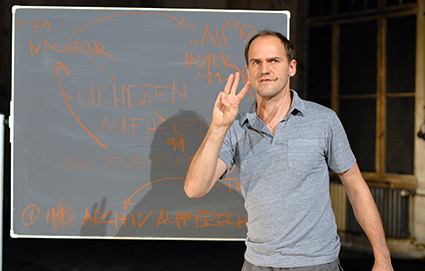

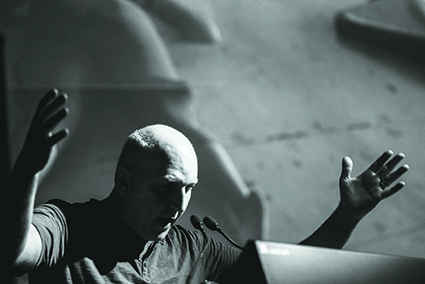

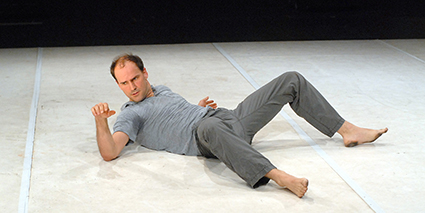

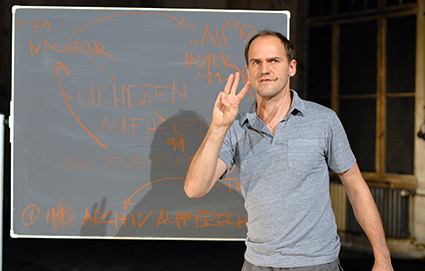

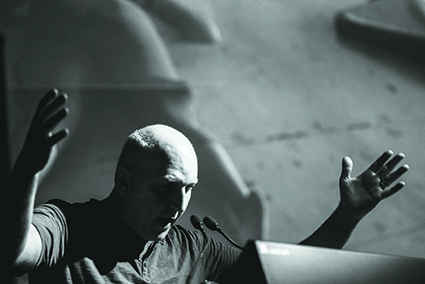

Martin Nachbar

photo Gehard Ludwig

Martin Nachbar

German choreographer Martin Nachbar sure kept himself busy during his three-city visit to Australia. In Brisbane he undertook research for his PhD, in Sydney he taught workshops and in Melbourne he presented one of his dance works.

Catching up with Nachbar in Sydney, I soon found out that this was not the first time he had been to Australia; his wife is Australian-born choreographer and performer Zoë Knights and he had previously accompanied her to visit family. This was, however, Nachbar’s first professional trip to Australia, on which he actively engaged with the local dance sector. In three capital cities no less.

Now based in Berlin, Nachbar studied at the School for New Dance Development (SNDO) in Amsterdam, in New York and at PARTS in Brussels. Since 2001, he has created more than 20 dance pieces, some of which have successfully toured internationally. During the last few years, his artistic focus has been on investigating walking practices, which is also the research topic of the trans-disciplinary PhD he is currently undertaking at Hamburg’s City University.

Brisbane

In fact, the main purpose of Nachbar’s residency in Brisbane—assisted by the Goethe-Institut—was to conduct research for his PhD. His thesis, Nachbar explains, asserts that performative group walking has the potential to create a stronger community, change urban life and increase contact between people. In addition to studying anthropological texts at the State Library of Queensland, Nachbar also participated in walking tours offered by the Aboriginal Cultural Centre in Brisbane’s city centre. Whereas these are mostly targeted at tourists, Nachbar himself has previously conducted walks of a more performative nature in the German cities of Berlin, Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Essen: “We invite a group of people, an audience, to walk with us, and we propose different modes of walking—backwards, forwards, really slow, really fast, homolateral [distinguishing between left and right body movement] and stomping. People can join us, or they can also step aside and watch.” The experiences of those participating in the walks are then charted through questionnaires.

Among the more unusual of Nachbar’s urban walking exercises is one that he calls the Quick Facade Walk: “The rule is that you stick to the facades of buildings as closely as you can. And whenever you come across an open door you have to go in, briefly explore the building or shop you’ve entered and then exit again.” And how do people, who are not part of the walks, react to this? Are the participants allowed to interact with them? “The walking exercises are usually conducted in silence to heighten the awareness for the sounds of the city. But yes, when people address you, you can answer.”

Sydney

Teaching a masterclass for students of Sydney Dance Company’s Pre-Professional Year (PPY) as well as conducting a workshop at the choreographic research centre Critical Path, Nachbar’s subject in Sydney was not walking but “Animal Dances.” The workshops drew on a project of the same title he undertook in Berlin in 2013 comprising both a solo and a group piece. As for what fuelled his interest in animal dances, Nachbar reveals: “[Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari have an important chapter in their book A Thousand Plateaus called Becoming Animal, Becoming Woman. They talk about how ‘a becoming’ is not an imitation. Imitation might be part of it but it’s not its foremost feature.” After a short pause, he adds: “And it’s true. Because there is a lot of imagination involved, a lot of feeling and sensation. But since this book has been read by people like Xavier Le Roy and many other choreographers, it feels as if it has become forbidden to imitate when working within the context of concept-driven dance in Europe. And I thought, hey, I’m going to give this a go. So I started off my research with imitating praying mantises, horses and birds.” And how did he go with that? “It was a lot of fun,” Nachbar laughs. “Because, of course, you’re immediately confronted by the impossibility of imitating. You have to draw on your imagination and it’s really challenging, both physically and mentally.”

Nachbar concedes that Animal Dances received its fair share of criticism, precisely because of its premise of humans imitating animals. He puts this down to the currently predominant view that representation is something to be avoided in the arts. As much as he understands, he says, the limitations of representation, he is uneasy about the prescriptive approach some reviewers and fellow artists adopt on the topic. “To say about any art work—you can’t do this, you can’t do that—is completely undemocratic. It’s ideologically motivated and not useful artistically.” Nachbar seems determined to keep challenging commonly held views as to what is allowed in the arts and what isn’t.

So, what is the connection between his walking performances and the choreographic concerns underpinning Animal Dances? “I used to think that I always work on different themes for each project and I couldn’t identify what my choreographic signature or overarching interest was. But I’m slowly beginning to get a sense of what it might be,” Nachbar laughs. One of his major concerns, he says is definitely the idea of ‘becoming:’ “It’s a very important aspect of my work. Even in the walking performances. You could, for example, say that they are about the human becoming human. Bi-pedal locomotion is what distinguishes us from all other animals.”

Martin Nachbar

photo Gehard Ludwig

Martin Nachbar

Melbourne

‘Becoming’ also plays a large part in the project Nachbar conducts in Melbourne, revolving around the reconstruction of the famous dance cycle Affectos Humanos by German expressionist dancer Dore Hoyer. The two-night presentation of his version of the work, was accompanied by a five-day workshop at Lucy Guerin Inc, part of the company’s Hot Bed program through which the work of international choreographers is introduced to the local dance community.

Nachbar’s research into reconstructing Hoyer’s seminal dance cycle began in 1999 and culminated in the creation of the piece Urheben Aufheben (2008) which he still tours. The original premiered in 1962 and a film of it was made in 1967. Working off the film was instrumental for Nachbar in orchestrating what he defines as a ‘meeting’ between Dore Hoyer and himself—across a timespan of over 40 years and two differently gendered bodies. He felt encouraged to do so by Hoyer herself. His research found that “she was interested in a particular unisex choreography in that piece.” He also was motivated by the impossibility of the task: “Knowing that I will neve be able to get rid of the differences, I had to embrace them.”

Nachbar admits that, from a modern day perspective, Hoyer’s choreography seems “strange and hermetic.” He says: “The question is how can you open it up to today and your own body, to think of reconstruction as a meeting rather than the attempt at perfect imitation.” These concerns were also to be explored in the then forthcoming, accompanying workshop: “I will ask the participants to choose one of the dances from Hoyer’s cycle [as glimpsed from her film] and devise a strategy for warming up for this particular dance.” This, Nachbar hopes, will allow participants to meet Hoyer’s work on their own terms, using their own skills. It’s the first time he’s run this workshop outside of Europe and he expresses great excitement about what the participants will come up with, especially given that Dore Hoyer plays no role in the Australian cultural consciousness. It will come down, he muses, to what strategies of ‘becoming’ each participant will devise for themselves.

Animal Dances Workshop, Critical Path, Sydney, 2-3 May; Hotbed Workshop #1, Lucy Guerin Inc, 4-9 May 2015; Urheben Aufheben, concept & dance Martin Nachbar, choreography Dore Hoyer, Martin Nachbar; presented at Lucy Guerin Inc, Melbourne, 8 & 9 May. Tour supported by Goethe-Institut.

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 34

© Martin del Amo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Glenn Thompson, Julie-Anne Long, 4’33’’ Into the Past

photo Heidrun Löhr

Glenn Thompson, Julie-Anne Long, 4’33’’ Into the Past

Despite a reluctance to do so, one can’t ignore saying something about John Cage’s performance 4’33’’ and the tradition within which this work sits. Why? Because even though Julie-Anne Long and Glenn Thompson do not directly perform this famously controversial score (musician on stage with instrument without playing said instrument over three movements in front of an audience) they do participate playfully and parodically with the provocations and propositions of Cage and others of this period historically labelled “happenings.”

Born on the stages of the Bauhausian influenced Black Mountain College with Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg, these experimental events reverberated east to New York, with the groovy gallery interactions of Alan Kaprow and the often lab-coated performances of Fluxus artists muttering and/or instructing their audiences through microphones

In the gallery spaces of Campbelltown Arts Centre the reverberation continues. Long in a white lab coat is busily collecting data and mapping the suburb and state electorates in which audience members live. We are not asked our earning bracket, but how much “actual cash” we have brought with us, “down to the last cent.” A record is made—the card swipers, pushers, tappers and wavers obvious among us. Meanwhile Thompson, also in lab coat, begins to drill holes in the gallery wall. A large plasma screen is mounted. The stage is divided. A drum kit played by Braxton Hegh from Campbelltown Performing Arts High School animates the first story of the past. High on the high hat with rock beat Lesson No. 5 underway, Thompson drops to his knees and recounts a ‘when I was young’ encounter; it’s nostalgically small, but character forming. On the margins of stage right we see the profile of Long directing someone offstage with tripod and camera, revealed on screen to be Georgia Briggs, also from CPAHS, who is “whipping it around” in a release based movement sequence: lesson, practice and warm-up.

The stage resets. There’s a bit of turntable rubbing from Long and an explosion of applause from a studio audience—not us from the Greater Sydney electorates, but artificial cheers jabbing at the space. Briggs sweeps through the space with her routine and a solar system appears on the plasma. All four dance a quirky number together, in white, in a white box with the galaxy glittering through a digital window.

Two microphone stands. Long and Thompson tell more stories of the past: were they formative in the emergence of arts practices? Hegh and Briggs sitting cross-legged flank Long and Thompson, left and right, in a perverse symmetry responding to these memoirs with simple mimicking gestures while plugged into their handheld devices. But where are their instructions coming from? The logic of transmission is unclear.

Long, helped by Briggs, returns to focus our attention on a faux-analysis of previously collected data. A map of the state electorates shows the density of attendance this evening, followed by an emerging pie chart on the monitor as a new galaxy representing how cashed up we are together: ca-ching! Use-value versus exchange-value suddenly takes on new meaning: could a coin really be a carrot rather than an abstract representation of it? But what is the point? Hmmm, my interpretive brain is working overtime here; am I taking Cage too seriously? Perhaps the point is no point: a pointless build to nowhere. This is the piece’s charm, along with a poke at earnestness. And for the askers of the why: why the hell not!

The Casio filtered voice of Long repeats the words “the contemporary dance” as we are plopped into an I♥NY loft scene, with Hegh strumming on acoustic guitar, Briggs leaning, coolly observant and Thompson wrapping his arms and hands around his head in a baroque twist to physically frame the retro-blurring of instrument, voice, image, movement and mood. A strong light beams in from stage left; the room thickens with smoky ice. Acceptance speeches in a canon run of overlapping “thank you’s” spoken into mics—doubling, trebling and quadrupling in the portal mist of a dying light.

The work feels less a happening than that things happened, offering us scenes, or better yet, events of not really knowing what or why, other than that we were ‘entertained’ by ‘art’ and fulfilled by the offering to “pay attention to what it is just as it is” (Cage 1957). Cage’s 4’33’’ is a paradoxical score about silence. Into the silence all we can hear is the noise. For Long and Thompson, the past—all we can find, and indeed applaud—is the present since the artists here are from where they were: Thompson, the little drummer from Queensland and Long “the prima batlet ballerina” (as she recorded in a childhood book of 1972 charting her then career) from suburban Auckland.

4’33’’ Into the Past was developed as part of the Campbelltown Arts Centre’s I can Hear Dancing Program (2012) initially curated by Emma Saunders and curatorially developed by Kiri Morcombe.

I can hear Dancing, 4’33’’ into the past; artists Julie-Anne Long, Glenn Thompson and collaborators, Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, 25 & 26 Sept

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 35

© Jodie McNeilly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Asian Ghost-ery Store, Crack Festival

photo Mitch Lee

Asian Ghost-ery Store, Crack Festival

Crack Theatre Festival is one third of the festivals that make up the annual Newcastle gathering This Is Not Art. Works in the 2015 program took place in makeshift performance spaces throughout the coastal town, most prominently in an abandoned BI LO supermarket, affectionately re-named The Crack House. The slogan “The Low Price People” is still faintly visible through the festive decorations that dress the gutted store, now a festival hub. It’s fitting that all performances are free. Artists aren’t paid, but the Australia Council’s Setting the Stages initiative covers travel costs for selected artists from around the country, making for a nationally curated program that feels like a relief for emerging independent artists from the pyramid scheme that governs most fringe festivals. Here is a safe space to experiment with new work that is raw but ready enough in a convivial setting.

Performances presented in the 2015 program often reflected the fraught tensions at play in the theatre-making process itself and the cultural, conceptual, political, pragmatic and representational concerns that follow.

Hectoring Apocalyptica

With the audience on a seating bank of steps descending from the rear entrance into The Crack House, Nathan Harrison stands before an arrangement of transparent plastic cups filled with water. He tells us that Hectoring Apocalyptica is about water security, about looking into the future while responding in the present. He expresses his trepidation in approaching the material, in wanting to do the issue justice without being silly or flippant. The reconciliation of this struggle to make political theatre manifests in the form of speculative stage descriptions which—read from clipboards by the performers—suggest what the show might be like. They vary from the fantastical to the self-deprecating, embodying a sense of futility in trying to represent the issue and be self-reflexive to the point of speculating on audience responses to the work. These readings punctuate the actual show as a series of demonstrative acts in which facts and figures are personified by the audience wearing character nametags in order to perform the artists’ research, and in which the cups of water become props.

Audience members play farmers and countries in negotiations for scarce water in which repercussions are discussed ecisions are made. In another sequence facts arrive amid game show-like activity that exposes coffee as requiring more water to produce than most western delicacies, much to the shock of the audience. We are continually removed from the gravity of this material by pointedly silly stage descriptions, culminating in the suggestion that when we leave the show, we leave with hope, and with the final repeated refrain, “the oceans never rise.”

Asian Ghost-ery Store

Asian Ghost-ery Store begins with two performers sitting casually on stage eating Hello Panda biscuits. They discuss how they might make a post-racial show that avoids Asian-Australian clichés and stereotypes and what such a show might look and feel like. Through this simple and personable beginning the friendly rapport between the two establishes an entertaining framework for anecdote and parody. Despite their expressed desire to go beyond the typical cultural parodies that frustrate them, they never really do. Through an awareness of this though they manage a sharp parody of cultural representation itself.

The work is a funny reflection on young artists grappling with the representation of cultures they are proud of but by which they don’t necessarily define themselves. The strength of the performance is in the hubristic storytelling and personal narratives that the pair engage in, referring to each other by the nicknames Shan and Yaya. As an example of a focus that is both inwards and outwards, at one point Shan teases Yaya for only having white boyfriends, presenting her as both victim and perpetrator of orientalism. Their banter culminates with a white-faced period-drama pantomime, Shan performing an abstracted strip dance so that the predominantly white audience can “get more used to Asian cock.”

They’ve Already Won

Harriet Gillies and Pierce Wilcox in They’ve Already Won stand onstage in corporate attire either side of a projection of a desktop computer, on which one opens a text edit document of a ‘script’ for the show. It continually links to web pages and YouTube videos repurposed as found material and performance texts for the performers’ sardonic reflections on the end of the world and the death of us all. They craft logic with their schizophrenic pastiche of seemingly disparate sources. This is the world that young theatre artists live in where theatre struggles to compete with the internet, which itself possesses a theatrical potential that the stage does not. Gillies and Wilcox revel in this futility of representation, without directly acknowledging it in the conceit of their presentational mode of performance.

They do give a hammed-up performance of a scene from Ruben Guthrie (2015), exposing a terseness in the writing of Brendan Cowell. Later Wilcox goes to deliver a piece of poetry but Gillies protests the reading of work by a white male European poet. In a recurring ditzy persona Gilles struggles to name even three female poets and scrolls Buzzfeed articles while Wilcox talks on the history of the Congo (because “politics is boring”). Theirs is a cumulative expression of disenchantment for the theatre and simultaneously a display of appreciation for its history, which informs what they do.

YouTube music videos which punctuate proceedings are danced to by the pair. A scene of absurd rolling around the stage to the Johnny Cash cover of “Hurt” suggests catharsis is of no interest (and maybe has no place). This is testified to in the closing when we are handed Mars Bars melted in their wrappers and watch a YouTube video of a man having a terrible day at work.

Business Unfinished; Home

In Home and Business Unfinished solo male performers present verbatim content of material gathered from others. The content of the first is in the title: the idea of home, homes born into and homes made by subjects interviewed who ranged from migrants to the homeless to people recently released from gaol. Their musings are delivered in measured tones, relayed via headphones. In Business Unfinished the material is of supernatural encounters. The disembodied voices of the interviewees telling their stories are played over the sound system and impeccably mimed by the performers. Both shows use the unpacking of boxes as metaphor in a simple theatricalising of their subject matter. They also share a focus on how best to represent their subjects by using their voices, the different verbatim approaches capturing a sense of authenticity. It will be interesting to see how each of these works evolves.

Little wonder that young and independent artists focus on the fraught demands of making performance work given the gutting of the Australia Council to establish the National Program for Excellence in the Arts, now Catalyst. Whatever the cause for this introspective turn, it represents an awareness and self-reflexivity ultimately born of artists sharing the same cultural climate as their audience. By providing artists with the opportunity to test their visions, The Crack Theatre Festival is fostering the excellence of tomorrow.

Crack Theatre Festival, Hectoring Apocalyptica, artists Nathan Harrison, Jacob Pember, Rachel Roberts and Emma McManus; Asian Ghost-ery Store, artists Shannan Lim, Vidya Rajan; They’ve Already Won, artists Harriet Gillies and Pierce Wilcox; Business Unfinished artists Robert Maxwell, Maeve Mhairi MacGregor; Home, Tom Christophersen, Nick Atkins, Crack Theatre, Newcastle, Oct 1-4

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 36

© Malcolm Whittaker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Geoffrey Rush, Max Cullen, King Lear, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Heidrun Löhr

Geoffrey Rush, Max Cullen, King Lear, Sydney Theatre Company

Insanity took centrestage in major productions in Sydney of Shakespeare’s King Lear and Fausto Romitelli’s An Index of Metals. In each the rupturing of a personal relationship yields terrible consequences. In Lear we watch the whole process unfold, in An Index of Metals we enter the mind of a woman living out the aftermath.

STC, King Lear

Geoffrey Rush’s Lear is elegant and stentorian—gravely and boldly voiced without ever being stock ‘Shakespearean’ in his delivery. Chest thrust out, he holds his head high. He’s robust, sweeping about the stage, but easily battered by emotional shocks that propel hand to heart and have him seeking out chairs either side of the stage, caving in, chest sunken, before angrily rallying. The anger is palpably raw but so is the personal pain his old age cannot immure him to. We already sense an emotional complexity that will unleash the madness he already fears and which will ultimately engender his short-lived salvation.

Rush brings to Lear a contemporary gravitas, underlined by the production’s initial setting, its opening scene akin to a party at an upper end reception centre or RSL club, men in dinner suits, women grandly frocked, some aptly kitsch entertainment from the Fool, tinsel and speeches at a microphone. This Lear has the appearance of an elder statesman and indeed looks mightily like Malcolm Fraser in country cap and long coat in scenes that follow. Rush perfectly embodies Lear’s bewildered, mad and sad trajectory right to its dark conclusion, the aged body increasingly weakening, memory fading save for the small jolts of recollection that return him to a tormenting real world. But the journey is critically interrupted and it’s not Rush’s fault.

The first part of Neil Armfield’s production, designed by Robert Cousins, is set in a vast empty black-walled space, filled with machination and misjudgement and only tinsel, microphone and costuming to minimally evoke location. In the second part there’s an edgeless, depthless white space—modulated by mist and subtle pastels—rapidly emptying of life but finally admitting of love and nuance. In between is the storm and Lear’s refuge on the heath. For a production excelling in minimal design that foregrounds action and emotion, the storm scene is astonishingly overwrought—the black walls slide up to partly reveal a white expanse against which we see an enormous volume of heavy rain flooding the stage, while live percussion thunders at the expense of words as Lear runs towards a huge industrial-scale fan to the side of the stage that fiercely pumps wind and mist. What’s lost is our direct contact with Lear, here he’s in profile braving the blast, and, above all, the fine balance between the inner and outer storms, the superfluity of the latter here scuttling the connection. Recovery is quick, but we have been rattled for the wrong reasons. Likewise, some devices that start out well are sustained too long after their framing of the initial scenes—the use of the microphone and the ba-boom drum beats that climax the Fool’s witticisms—instead of letting them fade as mood and circumstances change.

Also out of kilter was Meyne Wyatt’s powerful performance as Edmund, big and loud (and louder with microphone) as if dropping in from a performance of a play by one of Shakespeare’s revenge tragedy peers of the 1590s.

Otherwise performances all round were uniformly strong and subtly modulated, with licence given, of course, to Mark Leonard Winter’s excellent, naked Poor Tom to run mad and slide gleefully across the wet heath. This was a memorable if flawed Lear but the acting, the seamless transitions from scene to scene, the design and lighting (Nick Schlieper), Alice Babidge’s costumes and the live music (John Rodgers with Simon Barker and Phil Slater in a fine take on drums and trumpets), added up to an almost satisfying whole. Perhaps the storm scene will be recalibrated. I hope so. Best of all is Geoffrey Rush’s performance although there are many who have cast him forever as inspired clown and will let him be nothing other, missing what a superbly embodied Lear he has given us.

An Index of Metals, Sydney Chamber Opera

photo Zan Wimberley

An Index of Metals, Sydney Chamber Opera

Sydney Chamber Opera, Ensemble Offspring, An Index of Metals

Director Kip Williams has responded to the late Fausto Romitelli’s An Index of Metals—for instrumental ensemble, electronics and two electric guitars—by creating a scenario for a psychodrama suggested by the work’s fragmentary poetic text from Kenka Lekovich. It’s monumentally framed by three walls and a ceiling of some 200 lights that suggest a surreal padded cell or place of interrogation writ large. They function in enormous waves, reflecting the surging emotional states of a lone woman (soprano Jane Sheldon) attempting to come to grips with the breakdown of her relationship with ‘Brad’ (of Roy Lichenstein’s pop-art masterpiece Drowning Girl: “I don’t care, I’d rather drown than call Brad for help”). The sense of drowning is amplified with descending glides, both gentle and vertiginous, from the orchestra and, grippingly, from Sheldon.

The protagonist’s mental condition is portrayed as neurotic with her compulsively repeated tipping over of a vase of red roses and her chair on an otherwise empty stage until, neurosis turning to psychosis, she conjures a man, clearly the object of her thwarted desire, whom he she undresses and soon multiplies into five more naked men. Counterpointing, and not competing with, Romitelli’s dense, propulsive score and Lekovich’s evocative phrasings (that include the metals of the title: iron, copper, nickel, lithium and rust with their various resonances), Williams wisely keeps stage action spare save for several critical passages. Initially closed in on herself, the woman is hoisted high multiple times on her chair by the men, out of darkness into light, until she gradually opens out, extending a leg, drawing up her dress and leaning exultantly back. It’s a temporary erotic reprieve and prelude to her own nakedness—a profound vulnerability—and suicide (the music painfully and metallically grand). But in a hyperbolic ending the woman is rejoined by the men, equally blood drenched, as if she has exorcised herself of Brad in the very act of self-destruction. The accompanying, deeply melancholic adagio is followed by a final dark enigmatic guitar passage, confirming not only the powerful and often subtle role of the two instruments (Joe Manton, Cat Hope) throughout, but also recalling an intriguing phrase sung earlier by Sheldon in one of her four arias, “murdered by guitar.”

Jane Sheldon’s convincing evocation of advanced nervous breakdown and her sublime singing, Elisabeth Gadsby’s design and Ross Graham’s lighting and the combined instrumental forces of Sydney Chamber Opera and Ensemble Offspring, conducted as ever by Jack Symonds with passion and precision, came together to make an opera of An Index of Metals. Having the orchestra placed immediately before the audience meant that we could luxuriously immerse ourselves in the playing itself as Kip Williams’ direction carefully balanced sound and image. Meanwhile we were surrounded by glorious real time electronics operated by Bob Scott. Although the pulsing of waves of light in which the woman is drowning and the final bloodiness seemed overwrought and at times archly stagey and the movement and demeanour of the men too abstracted, Kip William’s fidelity to Lekovich’s text and his dramatic expansion of it proved to be an admirable venture for all parties involved and another step forward for adventurous opera in a Sydney greedy for it.

Sydney Theatre Company, King Lear, writer William Shakespeare, Sydney Theatre, 28 Nov, 2015-9 Jan, 2016; Carriageworks, Sydney Chamber Opera & Ensemble Offspring: An Index of Metals, Carriageworks, Sydney, 16-19 Nov

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 37

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Prize Fighter, La Boite Theatre, Brisbane Festival

photo Dylan Evans

Prize Fighter, La Boite Theatre, Brisbane Festival

This year’s Brisbane Festival was carefully shaped by brave programming and warm place-making, where even the large public festival spaces like Arcadia and the Theatre Republic felt like private house parties rather than public way stations. The dance between popular and worthy has always been a difficult one for the festival and incoming Artistic Director David Berthold seemed acutely aware of this, stating on his blog, Carving in Snow, soon after his appointment that “the gap between what artists want to make and what audiences want to see is now wider than I’ve ever known it.”

Yet the unflinchingly radical message about the violence perpetrated on the bodies of black men in America produced the most heavily promoted image of the festival advertising—two young Afro-American men, in hoods, circling each other, their bodies contorted into impossible extensions. As well, the cabaret Coup Fatal—where Congolese artists worked with Belgian choreographer Alain Platel to explore intractably difficult political and cultural issues in the Congo—threw off any pallor of worthiness with exuberant virtuosity. This was one of the magic tricks that Berthold managed in his tenure at LaBoite: selecting work that might on paper appear too edgy for conservative Brisbane audiences but that attracted them nonetheless through sheer energy and visual impact.

Ditto with the local work, including the saucy, politically punchy all brown ladies cabaret Hot Brown Honey at the Judith Wright Centre, and the two most commented on local works in this year’s festival: La Boite’s Prize Fighter—the debut of Congolese-Australian Future D Fidel—and the Queensland Theatre Company’s The Seagull adapted from Chekhov and written and directed by Brisbane wunderkind Daniel Evans.

Prize Fighter

Prize Fighter was the most anticipated show of the year from the moment of its announcement by former Artistic Director of LaBoite, Chris Kohn, who is most responsible for its incubation. The conceit of the show as an actual boxing match in real time was a powerful one and demonstrates Fidel’s strong instincts as a playwright. The match was flawlessly brought to life in production by deft direction from Todd MacDonald, elegant design by Bill Haycock and technical wizardry by lighting designer David Walters.

What was also extraordinary about the work was its showcasing of the breadth of African-Australian talent in this country with local performers Pacharo and Gideon Mzembe matched by recent NIDA graduate Thuso Lekwape and veteran American-Australian performer Kenneth Ransom. The opening night felt genuinely significant, evoking descriptions of the first night of Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman’s Seven Stages of Grieving at Metro Arts in the 1990s. For me, Prize Fighter felt not quite finished. Despite the obvious talent of the playwright, some of the writing seemed sketchy and the deeper ideas of redemption and trauma had not quite integrated the pivotal relationship in the work, that between the feisty trainer played by the redoubtable Margi Brown Ash and the doggedly heroic boxer trying to knit together a psyche torn apart by experiences of true horror. When the show tours, which it must, I have no doubt there will be time to deepen and integrate what is an important new work in the canon.

The Seagull

In direct contrast to the raw and stripped back Prize Fighter was Daniel Evans’ adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, which played out in a hoarder’s paradise—a set full of domestic detritus where stage manager Daniel Sinclair pottered around, moving pieces of the set and organising the quotes from Chekhov projected regularly onto the side wall of the Bille Brown Studio. I am not a Chekhov devotee, so although familiar with the story I came to Evans’ adaptation with relatively naïve eyes.

This is one of the most talented casts assembled in local memory but it was Brian Lucas’ performance as the mischievous and delusional dementia patient Soren that was at the heart of the adaptation. He spent the second half of the piece clutching the seagull shot by Trigorin. It was embalmed and spoke to him alone in the voice of Chekhov.

Lucas’ embodied and melancholic performance signalled what might have been for this work with more time and without the punishing dual role of writer/director. Evans’ previous adaptation for QTC, Oedipus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, was brave and wild, but exactingly disciplined in form and structure and displayed his longstanding preoccupation with Australian suburbia, a great leitmotif of Australian performance. The Seagull, for all of its self conscious disdain of Chekhovian mannerisms as boring and its meta-theatrical referencing of the tired controversies around adaptation, still faithfully adhered to all of the major story arcs and themes of the original.

This left those in the audience attached to the original in a real conundrum: if as a writer you literally excise Chekhov and try to fit your thoughts about art and life back into a Chekhovian shaped hole, you offer yourself up for direct comparison. While there was all of Evans’ vivisectional, generationally savvy, observational humour and flashes of sly brilliance, so much of it felt, well, petty. Yet in those sequences with Soren you felt the tingle of what could have been from one of Brisbane’s most daring and talented writers.

Theatre Republic

Across the river at Theatre Republic, the venue beautifully designed by Sarah Winter and program curated by La Boite Creative Producer Glyn Davies, it was business as usual with a mix of independent work from around the country. This included Attica Erratica’s disturbing reboot of the biblical story of Lot, The City They Burned, and the effortlessly charming political satire Richard II by Mark Wilson for MKA, another adaptation, but one that takes a range of Shakespeare’s history plays to pillory the current bloody federal political landscape. The loose brilliance of Wilson’s renditions of Shakespeare’s text scattered through the work was bettered only by his ability to rant: my favourite his tribute to Paul Keating. The fake golden velveteen of the set was gorgeous and the crisp by-play with Gillard cipher Olivia Monticciolo delicious, though the currency of the show did suffer from a climax tied to the rise of the then freshly deposed Tony Abbott.

Experimenta Recharge

Just adjacent to the Theatre Republic was one of the gems of the festival: Experimenta Recharge: 6th International Biennial of Media Art, with a dizzying range of visually beautiful and politically witty media art. While many of the pieces invited a traditional gaze—framed on walls or mounted in installation—their lurid colours disguised a slightly askew technological formalism that gave them an eerie depth. My undisputed favourite was a technicolour panaroma by Japanese collective TeamLab, 100 years sea, that rolls out animated verdant green islands across a pulsating aquamarine sea and changes subtly as it literally maps sea levels rising, minute by minute.

The last word though must go to the evangelically mesmerising American theatre director Peter Sellars. He suggested that there is a crisis of imagination in contemporary culture that only artists can solve by providing new models for work and collaboration. He ended his talk with a final provocation, urging the beleagured Australian arts sector to find solidarity and comfort with other communities straining under the weight of poverty and shrinking funding. In fact he claimed that it may well be in the work that we are now forced to do outside of our own art that we will find the fuel to create new approaches that could eventually change the world.

Brisbane Festival: La Boite, Prize Fighter, Roundhouse, 5-26 Sept; QTC, The Seagull, Bille Brown Studio, 29 Aug-26 Sept; Theatre Republic: MKA Theatre of New Writing, Richard II, The Loft, QUT, 22-26 Sept; Experimenta Recharge, The Block, Creative Industries Precinct, QUT, 8-26 Sept; Brisbane Festival, 5-26 Sept

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 38

© Kathryn Kelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Importance of Being Earnest, Wild Rice

photo courtesy Brisbane Festival

The Importance of Being Earnest, Wild Rice

I’m going to be very honest here and admit that there have been years recently where the Brisbane Festival has come and gone and I haven’t really registered that it’s on. Riverfire (the festival’s culminating firework spectacular) happens, sneaking up and strafing me as an annual wake-up call to say that it’s all just finished. The Theatre Republic, hosted by La Boite (curated by Glyn Roberts under David Berthold’s jurisdiction as then Artistic Director) was my viewing highlight last year, and a highlight again in 2015, but this time with Berthold at the helm of the festival itself, it felt an integrated part of a rejuvenated and eclectic program. Chris Ioan Roberts’ Dead Royal contained some deliciously scabrous writing in his coruscating dissection of the private lives of women who marry royals (think Dorothy Parker meets Joan Rivers) and Dead Centre/Sea Wall was a compelling study of grief. In that context, It was gratifying to see Thomas Quirk’s locally sourced The Theory of Everything take its place alongside the Melbourne-heavy national (and indeed, international) line-up.

Thomas Quirk, The Theory of Everything

Quirk’s tightly scripted anarchy (‘contributed to’ by J M Donellan and Marcel Dorney) had the feel of improvisation and managed to sustain focus for its tight 60-minute span. During that time we see the ensemble cast (Ellen Bailey, Thomas Bartsch, Katy Cotter, Chris Farrell, Coleman Grehan, Dale Thornburn, Merlynn Tong and Reuben Witsenhuysen) announce themselves as actors attempting to explain the formulation of the universe and meaning of life in post-dramatic montage fashion. Actually, they all announce themselves as creator Thomas Quirk at one point. They ‘shoot’ each other playfully to fight for the soapbox in one scene, then transform into iconoclastic thinkers of the past two thousand years—Aristotle, Newton, Einstein, Darwin, Warhol (!) et al, then personalise the search for the meaning of existence, then comment meta-theatrically on the fact that that’s what they’re doing. It’s a riotous theatrical experiment that somehow conjures up Kenny Everett’s spirit of anarchic comic ridiculousness for me. I look forward to seeing how Quirk’s work develops.

As for the broader festival program, there was a distinct postcolonial bias to the line-up, with dance, opera and theatre pieces from Africa and South-East Asia proving popular highlights.

Wild Rice, The Importance of Being Earnest

From Singapore, Wild Rice’s all-male version of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest was a delicious confection. The play is cast entirely with male actors from Singapore’s evidently deep talent pool. The conceit could have proven gimmicky, but it rose above queer parody for me. While the energy was high and camp and paced at the frenetic end of the farce spectrum, the pitch was just right. The outlandishness of the plot was overplayed, inviting the audience in to laugh at its ridiculousness. We weren’t laughing because Cecily and Gwendolyn (Gavin Yap and Chua Enlai) were men playing girls falling for men. We were laughing because Wilde’s text somehow felt fresh and raucous again under Glen Goei’s direction. The colour scheme was smart, austere black and white (though the set did feel like it had been whacked up for a quick bump in and bump out—something that wouldn’t cause headaches in the luggage hold). A string quartet from the Queensland Conservatorium provided fitting period ambience. And Ivan Heng’s Lady Bracknell was appropriately withering and evocative of Maggie Smith at her caustic, distingué Downton Abbey best. The cast was uniformly excellent. Hanging over it all was the knowledge that this theatre company really does push the envelope in socially conservative Singapore, and while the text’s queerness is safe enough to ‘pass’ as British panto here (and there), this production enabled me to re-access the piece and feel something of the frisson of salaciousness that no doubt attended its original performance. Social media tells me that at least one QPAC dowager subscriber was outraged by the all-male inversion of the text. “And they’re all Asian!” she evidently loudly declared. If those feathers alone have been ruffled by this joyous production, it’s been worth it.

Macbeth

photo Nicky Newman

Macbeth

Third World Bunfight, Macbeth

Brett Bailey’s reconceptualisation of Verdi’s Macbeth was an altogether more sinister affair. Bailey’s company, Third World Bunfight, is committedly engaged with socio-political commentary in South Africa. The central conceit is that a troupe of East Congolese refugee performers stumble across a trunk full of musical scores and costumes that once belonged to a local amateur opera company who performed Verdi’s Macbeth. They use the outfits to tell their country’s own story of colonial corruption. That premise was something of a dramaturgical leap of faith, and not one I’m convinced was brokered clearly in performance. Once it was up and running, though, things cohered more clearly. Here, the three witches are converted into voracious mining company executives whose augury sees installation of a regime supportive of their own rapacious ambitions for the country’s resources. Macbeth (Owen Metsileng) is the corrupt puppet who benefits and grows decadent on his country’s imperial exploitation. The scene where he and Lady Macbeth (Nobulumko Mngxekeza) transform into booty-grinding bling-clad hip-hopsters (singing to the original Verdi score) is the highlight and the moment, for me, when the adaptation—the collision of parent text and contemporary interpretation—crystallised most successfully in performance.

It didn’t always feel like the audience was ‘there’ with the piece. There was some inane giggling whenever the word “fuck” appeared in the surtitled translation of the text, and despite the excellence of the singing by the entire cast, I sensed some audience detachment for long stretches. Perhaps this is, again, a dramaturgical problem with a parent text that doesn’t quite know when to end. As Berthold writes in the program foreword “Shakespeare’s play and Verdi’s opera are, I think, flawed works that very often fail to ignite in the theatre.” At various points, there are Brechtian interventions in the form of projected biographies of the chorus performers. We learn that several of these singers are themselves either former child soldiers or first-hand survivors of the Congolese wars, and suddenly, despite the didactic way in which this knowledge is introduced, the piece resonates more deeply. The musicians too (the No Borders Orchestra from central and eastern Europe) are reminders, as Berthold notes, that “homelands are torn apart in many parts of the world.” When the singers and the orchestra embrace each other during the curtain call, there is a theatre-wide standing ovation and that earlier disengagement is forgotten. The piece is, ultimately, a triumph of compassion over human greed and rapacity.

Brisbane Festival: The Theory of Everything, deviser, director Thomas Quirk, presented in association with Metro Arts, Theatre Republic, La Boite Studio, 15-19 Sept; Wild Rice, The Importance of Being Earnest, QPAC Playhouse, 11-13 Sept; Third World Bunfight, Macbeth, concept, direction, design Brett Bailey, QPAC Playhouse, 15-19 Sept

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 39

© Stephen Carleton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

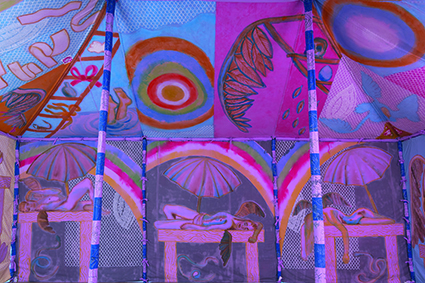

Carla Tilley in The Bacchae

photo Pia Johnson

Carla Tilley in The Bacchae

Melbourne in 2015 might be remembered as a place and time in which art took an unexpected turn towards the ecstatic. There was even an entire festival at our Arts Centre devoted to work that comes under the label. You could trace some genealogy back to trends in live art of recent years as well as durational dance works, the crossover of experimental sound art into more conventional theatre spaces and a shift away from irony and distance towards immersion and presence. But just as important has been the realisation that the hypnotic and trance-inducing needn’t be divorced from intellectual engagement. Stunning the senses doesn’t require the switching off of minds.

Two entries at this year’s Melbourne Festival left audiences truly dazed while also plumbing profound philosophical and political depths. Adena Jacobs’ and Aaron Orzech’s The Bacchae created havoc among audiences’ interpretative registers with its house-of-mirrors approach to voyeurism and the sexualisation of teenage bodies, while Andrew Schneider’s YOUARENOWHERE had many questioning the very reality into which they had somehow been dropped.

The Bacchae

To describe The Bacchae as Jacobs’ and Orzech’s work is a bit of a mistake, though it’s one that explains some of the concerned reactions several reviewers had to the piece. The pair are listed as co-creators (Jacobs directs with Orzech as dramaturg) but crucial to this free adaptation of Euripides’ text is the large ensemble of teenage girls whose responses to the original drama inform almost everything we see on stage.

Euripides’ tale is still here: the work begins with a murky, obtuse prologue in which a prostrate figure gives birth to an animal skull, alluding to the double birth of the god Dionysus. Pervy King Pentheus will make an appearance soon enough, too, and a recounting of the frenzied violence of the women on the mountain is directly drawn from the original tale. But for the most part the source material is dispersed across the bodies of the entire cast and refracted through a confronting teenage perspective.

Post birth-scene, a girl describes the boring rituals of her morning before announcing that she is Dionysus and will punish unbelievers. From here the rest of the work could be seen as a kind of increasingly ecstatic dance, beginning with the affectless stillness of a group sitting around staring at their phones or flipping through books and slowly building to a frenzied intensity of harrowing imagery and exulted obscenity. A hooded man with foam abs and a baseball bat stalks the space menacingly; a giant head with gaping maw inflates to take over most of the stage; a boy slouches listlessly on a sofa, staring dully at the eroticised spectacle unfolding before him.

It’s these erotics that have alarmed a few critics charging Jacobs with exploiting young girls for the audience’s gaze. The objection overlooks the fact that this is unmissably the point. The work’s most striking image occurs when a large portion of the cast appear in formation wearing bikinis and some kind of oil that renders their skin as shiny as plastic. Their heads are each bound in an opaque wrap that leaves them literally faceless. It’s as overt a representation of sexual objectification as one can imagine.

But the gaze here comes from the subjects themselves; or, rather, it is their own exaggeration of the gaze within which they are commonly framed. It’s not exactly news that the adolescent female body is sexualised in popular culture and that young women are treated as objects rather than subjects. It’s deeply unsettling to witness evidence that these same young women are highly aware of this, though. Rather than protesting that objectification, they here produce a nightmarish burlesque that amplifies it to an excruciating point.

It’s a brilliant enough move to ask young women to articulate their own subjugation of agency as they see others doing to them. To allow that othering of the self to escalate to such nightmarish levels is where the work goes one better. By its end, masked figures with giant hairy penises are humping every available surface and individuality has dissolved into a morass of animalistic violence and apathetic surrender. The bone-rattling oscillations of a modular synth crescendo while an onstage band has been beating out a tireless and insistent rhythm. The sustained spectacle of horror seems as if it will never end.

Then it does. The lights come up and it becomes shockingly apparent just how young these performers are. But as senses scramble to readjust to the everyday world, there’s the lingering understanding that the shit these girls are expected to put up with doesn’t end, really. It goes all the way back to Ancient Greece.

YOUARENOWHERE

YOUARENOWHERE is no less timeless in its reach. US artist Andrew Schneider performs alone, his shirtless torso wired up with various gadgets that allow for the live manipulation of his voice along with various other effects only his technicians probably understand. He delivers a wide-ranging monologue that jumps from autobiography to speculative physics, and by joining the dots it seems as if his ambition is nothing short of traversing the gap between possible universes. He kind of manages it.

The sophistication of the technology here is mindboggling. Schneider has in part been inspired by artists of light and space such as James Turrell. Through improbably precise manipulations of both Schneider is seemingly able to teleport across the stage in an instant or to cause parts of his body to simply vanish. The work’s great coup de théâtre—which nobody should ever, ever spoil—turns out to be less technical in nature and more the result of a sheer willingness to do what others daren’t try. Suffice it to say, it appears Andrew Schneider has achieved the impossible because the more likely scenario would be too hard for an artist to pull off.