Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

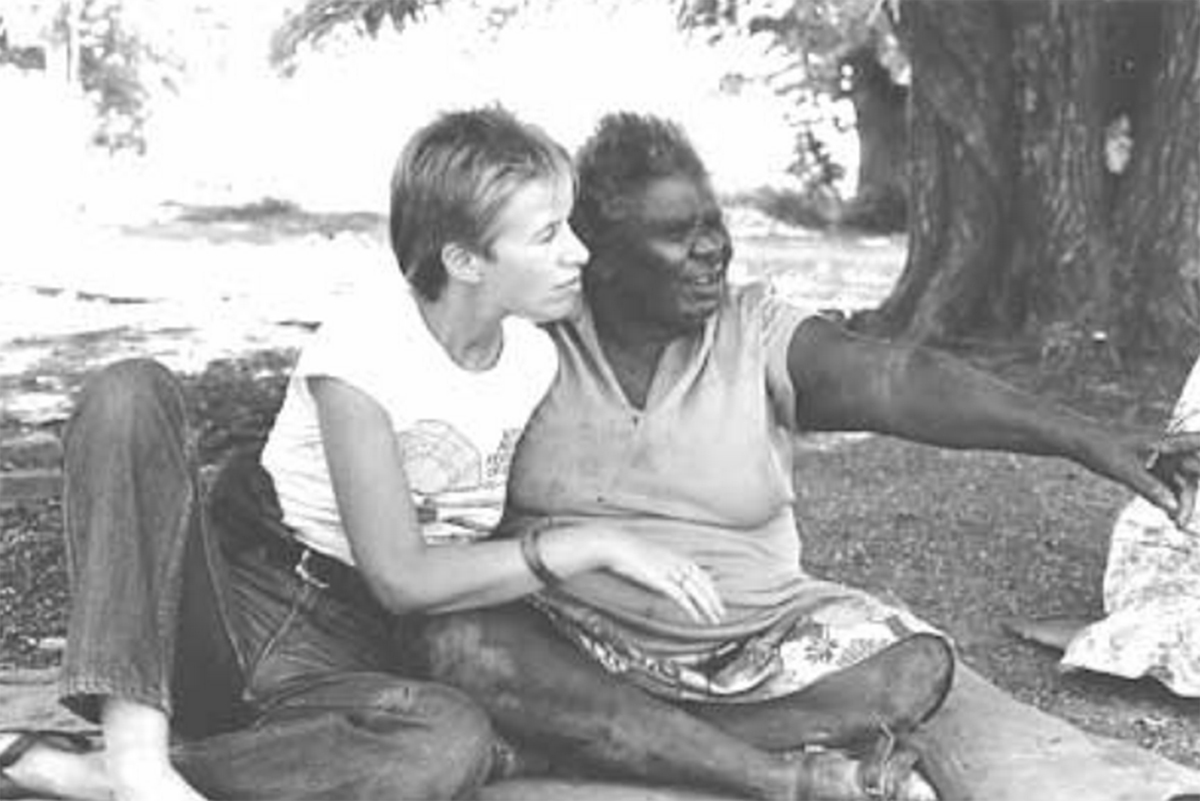

In The Second Woman, a hugely popular, cinematically framed durational performance created by female artists in Hobart’s Dark Mofo, Nat Randall [above] plays out one scene over and over, each time with a different man from the general public, yielding a telling variety of outcomes. At the Sydney Film Festival, rarely seen films made by women in Sydney in the 70s and 80s reveal the power and potential of feminist experimental and documentary filmmaking. Also at SFF and in her first film, Su Goldfish constructs a life of her father from fragments. At the MCA, Zanny Begg and Elise McLeod’s video work The City of Ladies provokes questions about the representation of women by women in utopian scenarios. We go to Tokyo with Philipa Rothfield and lend an ear to Mexico City with Ann Deslandes. We’re having a two-week mid-Winter break and, rested and energised, will be back with you on 19 July. If you haven’t yet donated to RealTime, please do so over the next two days; every dollar makes a difference for the arts. Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: Nat Randall and participant, The Second Woman, photo Zan Wimberley

In 1405, the writer Christine de Pizan produced a collection of alternative histories of women from literature and legend, interwoven with everyday observations of womanhood at the time. Unusually educated for a medieval woman, de Pizan was a champion of women’s abilities and The Book of the City of Ladies is widely considered to be the first feminist text. In de Pizan’s version of ancient European myths, women, previously represented as terrible witches by men, are recast as heroes. Through de Pizan’s desire to show women as steady, intelligent and kind, The Book of the City of Ladies shows that history as it might be written by women is very different to the one written by men.

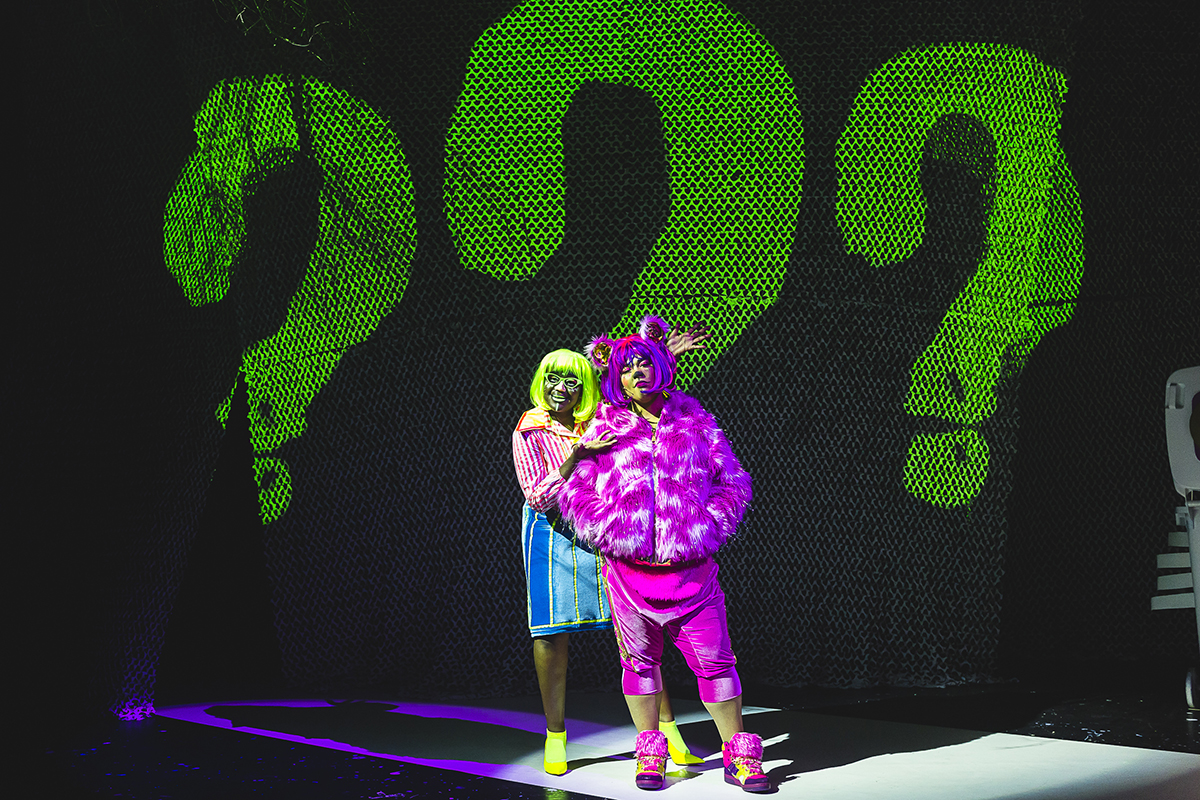

Drawing on de Pizan’s book, Australian artist Zanny Begg and Paris-based Australian filmmaker Elise McLeod have created their own collection of women’s stories in a film titled The City of Ladies. Recently screened at the MCA as part of The National, these stories are performed by a group of seven young Parisian women who play roles that draw on their real lives as activists as well as representing aspects of contemporary feminism. The women are bound by friendship, activism and the film’s central conceit: they are all auditioning for the role of Joan of Arc in an imagined production.

The film is designed to give the audience a fragmented, partial viewing experience. Made up of modular episodes that are configured each time by an algorithm, each viewer sees a different set of events. The episodes include scenes where the women participate in activist projects, a story that follows one of the women as she confronts everyday situations and a casting session where each of them auditions. In addition, several key feminist thinkers, including 20th century powerhouses Hélène Cixous and Silvia Frederici share their knowledge in sections edited to appear as if the young women are receiving a class.

The City of Ladies (still) 2017, by Zanny Begg with Elise McLeod, courtesy and © the artists, photo Federique Baraja

These interviews and the sequences that explore individual stories are, for me, the most engaging aspects of the work. In the stories I’ve seen, themes of race, class and gender fluidity emerge.

A young French-Asian woman helps her mother clean the apartment of a wealthy white woman. Left to finish the work on her own, the girl pretends she is the owner of the apartment. She puts on a leather jacket left hanging over a chair, tests the perfume on the mantelpiece, dances to a song on the stereo and reclines on the sofa with a copy of The Book of the City of Ladies.

A young French-African woman listens to her transgender friend tell a story about a man who agrees to beat his friend’s wife to win a bet. The wife narrowly escapes being murdered and lives the rest of her life as a man. A North African woman wonders where she fits as an African woman living in France and passing for white. Sharon Omankoy discusses afro-feminism.

There are some charming moments in The City of Ladies. The women are endearingly earnest, they face-swap each other into an internet image of Joan of Arc, and there is a lot of dancing. But I struggled to place the film within the context of The National, a survey of contemporary Australian artists held across the MCA, AGNSW and Carriageworks. The National is in part about creating and establishing Australian histories and while there’s something global about all 21st century experience, each place has its own particularities that influence how issues of colonialism, globalism and migration manifest in daily life. Because The City of Ladies explores these issues as they occur in Paris, I felt unable to use them to think through my own position and experience as a young 21st century woman. For example, France’s relationship to colonialism is significantly different from Australia’s, as is the way feminism has been theorised and enacted. Perhaps this response is specific to me, but within the context of the exhibition, I was looking for Australian responses to these questions.

The City of Ladies (detail) 2017, Zanny Begg with Elise McLeod, installation view, The National 2017, courtesy and © the artists and MCA, photo Jacquie Manning

Also difficult to reconcile is the film’s body-oriented image of feminism with my own thinking about how women are imaged. The camera work is empathetic and even-handed and the film attempts to challenge mainstream ideas of feminine beauty, but, by using conventional formal techniques — in particular, continuity editing and the use of coverage that is varied and doesn’t draw attention to the image’s construction — the film fails to address questions of representation as thoughtfully as it might. For me, two key, long-running questions are the objectification of white women and the invisibility of black women. Begg and McLeod’s film engages these to some degree. Black women are present, and white women are active, but all of them are pretty and when the camera roves closely over their young dancing bodies the image is not different enough from the problematically sexualised images of young women made by men to encourage the audience to reflect on how representation influences what women become.

Perhaps the artists imagine the shots as empowered images of young women that are joyfully sexual, or as a playful riff on the notion of putting women on a pedestal — there are sequences where the women actually dance on a pedestal. But the image feels contradictory because the film grammar, in particular the slow-motion close-ups, carries a history of feminist argument that has not yet been resolved. Some of these questions around how women might be represented in a feminist context are concurrently on display in Alex Martinis Roe’s It Was About Opening the Very Notion That There Was a Particular Perspective (2017) in The National at AGNSW and they are questions that still feel pressing. There is also the question of women’s technical roles within film production. One of the most positive feminist actions is to put women behind the camera, but the DOP on The City of Ladies is male.

What stays in my mind are the interviews with feminist theorists. Thoughtful and passionate, they are, like de Pizan’s writing, a sign that things might one day be different.

–

The City of Ladies, Zanny Begg and Elise McLeod, director of photography Laurent Chalet, performers Marie Rosselet Ruiz, Tasmin Jamlaoui, Sonia Amori, Juliette Speck, Coline Beal, Garance Kim, Katia Miran, voice David Seigneur, audio design James Brown, music Mere Women, La Catastrophe, La Parisienne Libérée; The National, curator Blair French; MCA, Sydney, 30 March-18 June

Sarinah Masukor is a writer and moving image maker. Her writing on film and contemporary art has been widely published here and overseas. She has worked as a presenter and critic for ABC Arts and Radio National and currently teaches Media Arts and Production at UTS.

Top image credit: The City of Ladies (still) 2017, Zanny Begg with Elise McLeod, courtesy and © the artists, photo Federique Baraja

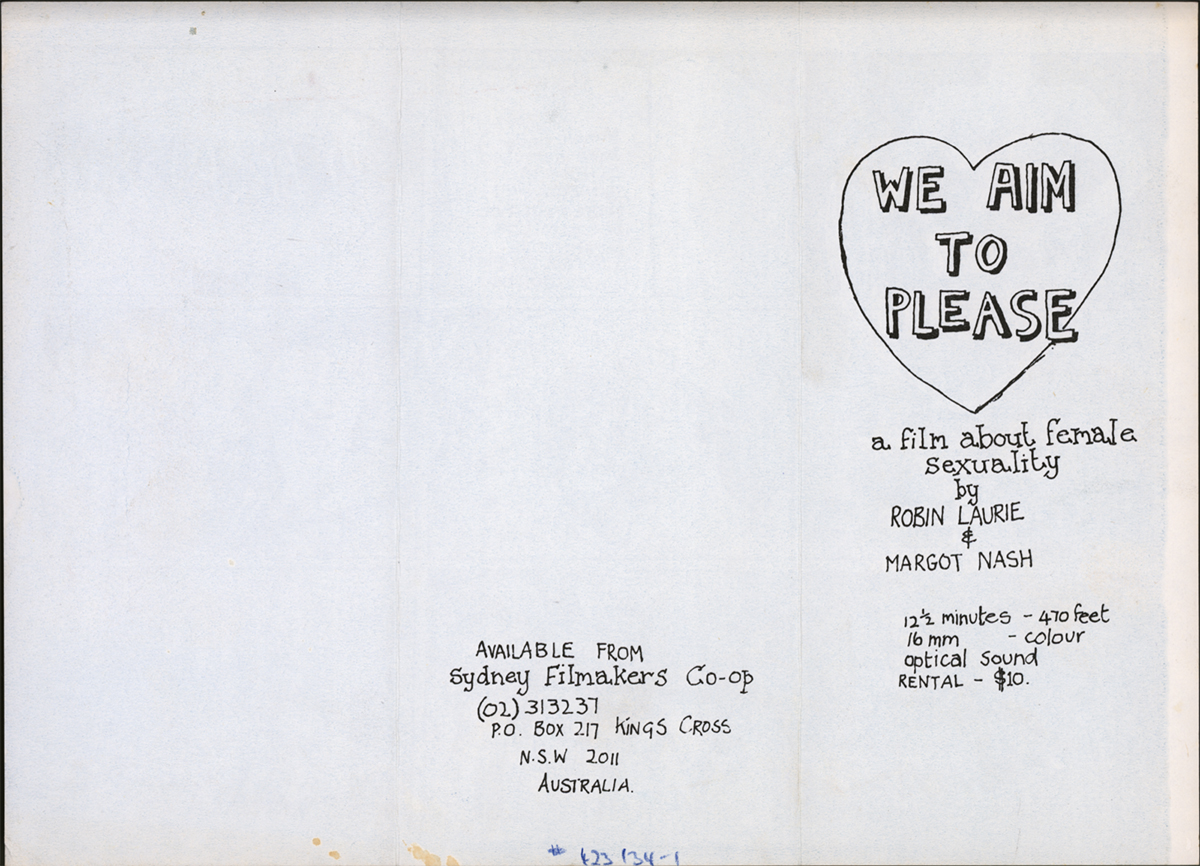

“I think it’s pretty rare for a woman to make a good film, they have to work from behind their oppression, which makes for some bummer movies.” Though these words are fictional — spoken by the titular antagonist of the television adaptation of Chris Kraus’ canonical I Love Dick (director Jill Soloway, 2017) — they ping-ponged around my mind during the three sessions of the Feminism and Film retrospective at the 2017 Sydney Film Festival. Susan Charlton’s finely curated program — Feminism and Film: Sydney Women Filmmakers, 1970s & 1980s — suggests that creating from behind your oppression can make for films that are entertaining, experimental and original, laterally conceptualised, carefully structured and beautifully shot. Comprising short films and documentaries, the Feminism and Film sessions were among the most compelling of the 20-plus screenings I attended at SFF over the course of 12 days.

We Aim to Please (1976)

Though indeed disparate in content and form, the films were united by their spiky, feminist tellings of history and experience, bristling with energy and verve. They all suggested a creative, political phase of feminism in Australia, and while I expected overtly feminist content — daily life, the mess of it, housework, stories of women’s lives — many works contested the very language of film, reaching for new ways to represent women onscreen. We Aim to Please (Robin Laurie and Margot Nash, 1976) was, like the new I Love Dick, all about women’s perspectives on desire that bucks the male gaze and the beauty myth. Satirical and irreverent, We Aim to Please ended up settling on very close-up shots, abstracting one of the filmmaker’s bodies, lying in the earth of a garden patch, pale goosebumps alongside green leaves. This was not an idealised vision: there was body hair and full nakedness without the politeness of a reclining nude or the airbrushed unreality of porn. This concern with finding visual ways for women to be subjects, not objects, even without clothes, recurred in almost all the films that followed.

For Love or Money: a history of women and work in Australia (1983)

For Love or Money (Megan McMurchy, Margot Nash, Margot Oliver and Jeni Thornley, 1983) was a highlight of incredibly dense, intelligent non-fiction storytelling. An essay film, it resurrected a staggering array of archival clips and synthesised the writings of feminist historians to construct a chronology of women at work in Australia. By opening with the equal and vital role of women in Indigenous societies, it slayed the idea that Australian history commences with colonisation, creating the ideal basis for advancing the film’s main thesis that under capitalism, women’s work (raising children, doing the bulk of domestic labour, performing emotional labour that keeps families and their partners afloat) is devalued in a way that lowers the stature of women themselves. In other words, sexism isn’t just a floating prejudice in the uneducated mind, but is anchored and legitimised in an economic reality. The film arcs through the ban on married mothers in the workforce, the campaign for equal pay, the rush of women into paid roles during World War II and the exploitation of migrant women. Though this description of a radical economic analysis probably suggests a super cerebral film, For Love or Money resonated at a deeply felt level. Noni Hazelhurst’s narration refused to engage in documentary cinema’s historical pretensions of objectivity, with constant reference to “our bodies,” “our pain” and “our survival.” For Love or Money stands today as a major work of historical research, a masterclass of montage editing and a classic essay film. It can be streamed from Ronin Films.

My Survival as an Aboriginal (1979)

The retrospective’s vital Indigenous component went further. The first Australian film by an Indigenous woman, My Survival as an Aboriginal (1979) is framed through the experience of Murruwurri matriarch and director Essie Coffey, whose strength and hope and struggle burn through every moment. Superbly structured, the documentary, filmed and co-produced by cinematographer Martha Ansara, tells of Indigenous depression initiated by the trauma of colonialism. A sequence in which Coffey shows Indigenous kids how to find food and medicine in the bush is followed by a blue-tinged, scripted segment in which a fridge door opens repeatedly onto a white-fluoro nightmare of processed foods, a jug of orange juice glowing nuclear. Coffey turns away from the fridge and stares down the camera with an ironic glint in her eyes, and we understand that happiness is an impossibility under Western imposition. We then see shots of drunken Aboriginal alienation — met with police repression — before going back to the bush with Coffey and her family: survival through community is the lasting message.

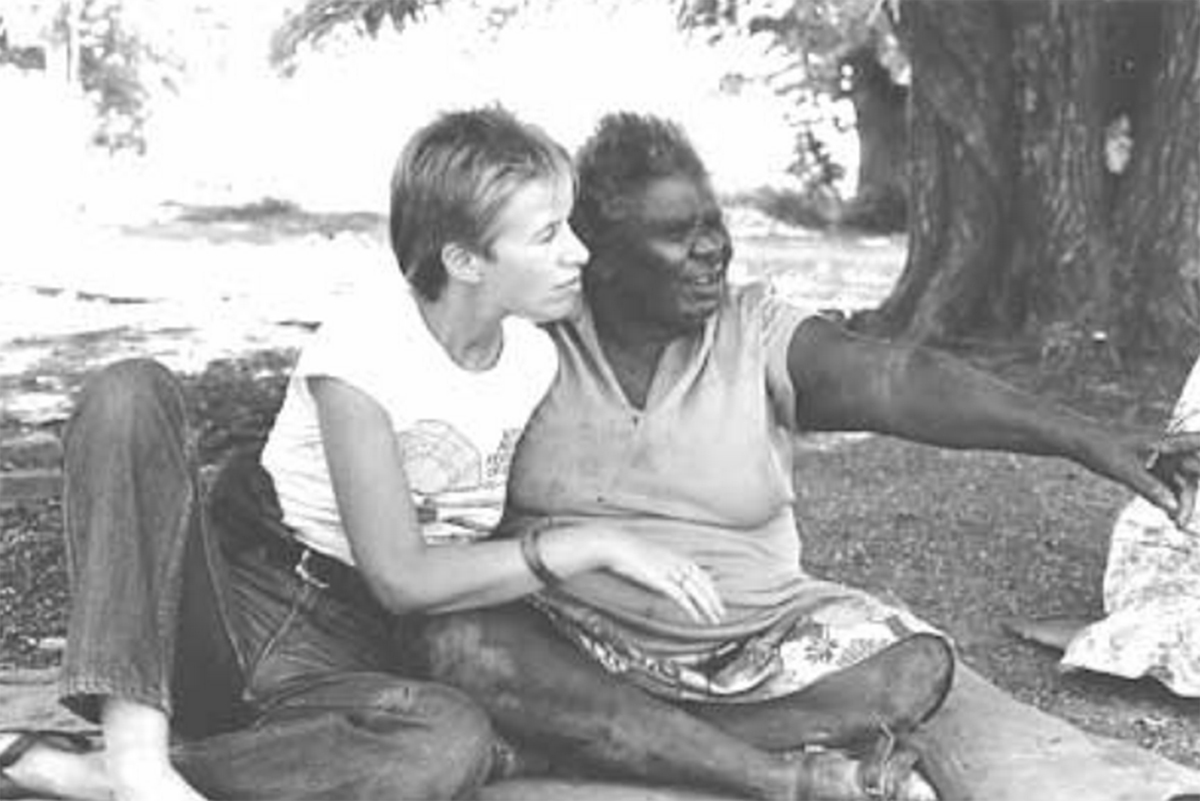

Carolyn Strachan and community member, Two Laws

Two Laws (1981)

Next was Two Laws, a documentary made collaboratively by the Borroloola Tribal Council and filmmakers Carolyn Strachan and Alessandro Cavadini (see excerpts). It tells of an awful moment of police and judicial brutality in the 1930s in the Northern Territory, with each storytelling decision made collectively by the surviving people of that community. The film has scripted moments and re-enactments but is entirely transparent in its presentation; much of it is shot, wide-angle, from a seated position among a circle of people, in visual sync with Indigenous storytelling traditions. I haven’t seen anything like it in honesty of feel or form, though it’s an obvious precursor to the sleeker fictional drama Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer, 2006).

The women’s film collectives

A common context emerged over the course of the retrospective: the filmmakers’ collectives that shaped much independent filmmaking in Australia in the 1970s, often involving people who began their creative training as artists. The Sydney Filmmakers’ Cooperative and the Women’s Film Group birthed combinations of art minds who encouraged and worked with each other with an ethos antithetical to today’s neoliberal, self-branding mentality. Many of the films benefited from the Experimental Film Fund, an Australian Film Institute program 1970-1978 for projects orphaned by commercial distributors and production houses. And in 1975, a Women’s Film Fund was created, resulting in films like the fantastical This Woman is Not a Car (Margaret Dodd, 1982), which presents suburban married life as a form of horror.

Consider this context for filmmaking against that of today. Federal support for experimental filmmaking is now zero. And an express vision for correcting rampant workplace discrimination against women in the screen industries has only just begun to form among policymakers, who remain hesitant to suggest concrete targets or quotas for parity in gender participation.

The lost/found paradox

The series performed another function: the revelation of an archive lost to the public imagination. The films are all preserved by the National Film and Sound Archive, but, without more concrete screening opportunities, are a lost legacy. It’s paradoxical to think that cultural objects can be both archived and lost. Though the NFSA’s mission is to collect and share items of audiovisual production, evidently much more collection than sharing takes place, with few options for big-screen or home viewing. The archive seems to be a one-way chute: archived but not circulating or discoverable, films go in and rarely go out, with digitisation, distribution and exhibition the missing links to their life in contemporary film-going.

Projections

The Feminism and Film series is over now but the retrospective highlighted the absence of state and industry structures crucial for the creation and delivery of innovative creative works: an experimental film fund, a better plan for digitising and providing access to archives, exhibition spaces for non-commercial films and the facilitation of discussions around them. Though I’ve heard much lamentation of inequity since the launch of Screen Australia’s rather spineless Gender Matters policy in 2015, I knew almost nothing until now of these women’s films that thrived in a living vein of supported film culture in the 1970s and 80s. To think that the beginnings of a tradition of politically acute, formally daring filmmaking by women in Australia was cut short, and then almost forgotten, says so much about the larger problems of cultural value and memory in Australian culture and screen industries. Despite their retrospective nature, the Feminism and Film screenings played like scenes from a possible future for Australian cinema: a reminder that culture can change, if we’re willing to look back before we look forward.

Other films in the program included Behind Closed Doors

(Sarah Gibson, Susan Lambert, 1980),

Serious Undertakings

(Helen Grace, Erika Addis, 1982), A Song of Ceylon

(Laleen Jayamanne, 1985) and Film for Discussion (Sydney Women’s Film Group, including Martha Ansara and Jeni Thornley, 1974).

–

Sydney Film Festival, Feminism and Film: Sydney Women Filmmakers, 1970s & 1980s, curator Susan Charlton, Sydney Film Festival, Event Cinemas and Art Gallery of New South Wales, 10 & 18 June

Top image credit: Archival still, For Love or Money

Manfred Goldfish is a man with a history, but like many of his generation who have lived with horrific memories of war and displacement, he is anxious to shield his daughter from his painful past. Selectively forgetful, he’s not always an easy subject for filmmaker Su Goldfish. Preferring to be known as simply “a citizen of the world,” he says, “I drew a line. I made a decision when you were born to never look back.”

Clearly he didn’t bargain on the determination of his daughter to painstakingly collect the familial threads and tie them together again and film the experience. We follow her as she pieces together a history beginning with her birth in Trinidad, one of the few countries accepting people like her father fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany. Though it involved a period of internment for Manfred, life in Trinidad is happy. He’s involved in the music industry and meets and marries Goldfish’s mother Phyllis who is on her way to somewhere else when she unaccountably disembarks at Port of Spain.

Young Su Goldfish with friend in Trinidad, The Last Goldfish

Faced with a reluctant subject, Goldfish seeks evidence in the generous family archive of photographs and her father’s home movie footage. Visually, the film relies heavily on these images as well as the filmmaker’s narration. Dog-eared black-and-white snaps and grainy film footage document the family’s happy life in Trinidad until their enforced departure following the 1970 Black Power Revolution and eventual migration to Australia, where the young Goldfish has to acknowledge that she’s white. Images change to crisp colour, marking the change from Caribbean to Antipodean light and with increasing candour that familiar distancing as Goldfish forms her own relationships and connections with the theatre and LGBTI communities. Her journey in Manfred’s colourful past is rendered in sepia tones and black and white images of before-and-after Europe extracted from family albums and leaving the marks of their disappearance.

At 80 minutes, attention is occasionally tested though the film largely maintains momentum as we’re caught up in what becomes for Goldfish an almost obsessive project over 10 years of her film’s development. When it’s revealed that Manfred has a previous family, the search becomes more urgent. Video complements the still images as she traces — often in photographs — ancestral footprints, identifying and returning to places once inhabited by relatives, placing pebbles on gravestones, authorising commemorative plaques laid by German authorities now eager to make restitution for past wrongs. Each new contact invites a journey and adds another surprising piece to the puzzle: she learns she’s Jewish. She despairs over a missed connection with another distant relation, now dead: “I could have known her!” Early on, Goldfish is perplexed when her letter to the half-brother she’s discovered goes unanswered. Later she learns of the psychological damage to his abandoned son that her father’s displacement has wrought.

Manfred in Europe, The Last Goldfish

A slower paced element of the film is Goldfish’s understated video interview with her father. Mostly filmed in close-up, Manfred responds cagily to his daughter’s gently probing questions. Later her camera silently observes the aged Manfred and Phyllis moving with difficulty through their home. The footage of Manfred Goldfish stands alone as a poignant portrait.

Connections with the current world refugee crisis are inevitable. Watching The Last Goldfish, we can’t help be reminded of the repercussions of displacement and just what’s involved in putting the pieces back together again.

Premiering at the Sydney Film Festival, The Last Goldfish is one of 10 Australian documentaries funded in part by the Documentary Australia Foundation.

–

The Last Goldfish, 2017, writer, director Su Goldfish, producer Carolyn Johnson, editor Martin Fox, distributor Umbrella Entertainment.

National cinema release, October, 2017

Top image credit: Manfred and Su Goldfish in Trinidad, still, The Last Goldfish

With the luxury of an international festival on my doorstep, I was on the hunt for non-mainstream outlooks, female directors, experimental approaches and films with an eerie edge. I found myself transported to some unexpected places by three striking features, two directed by women and offering insights into Thai and Afghan cultures, the other an affirming documentary about a community built on fictional horror.

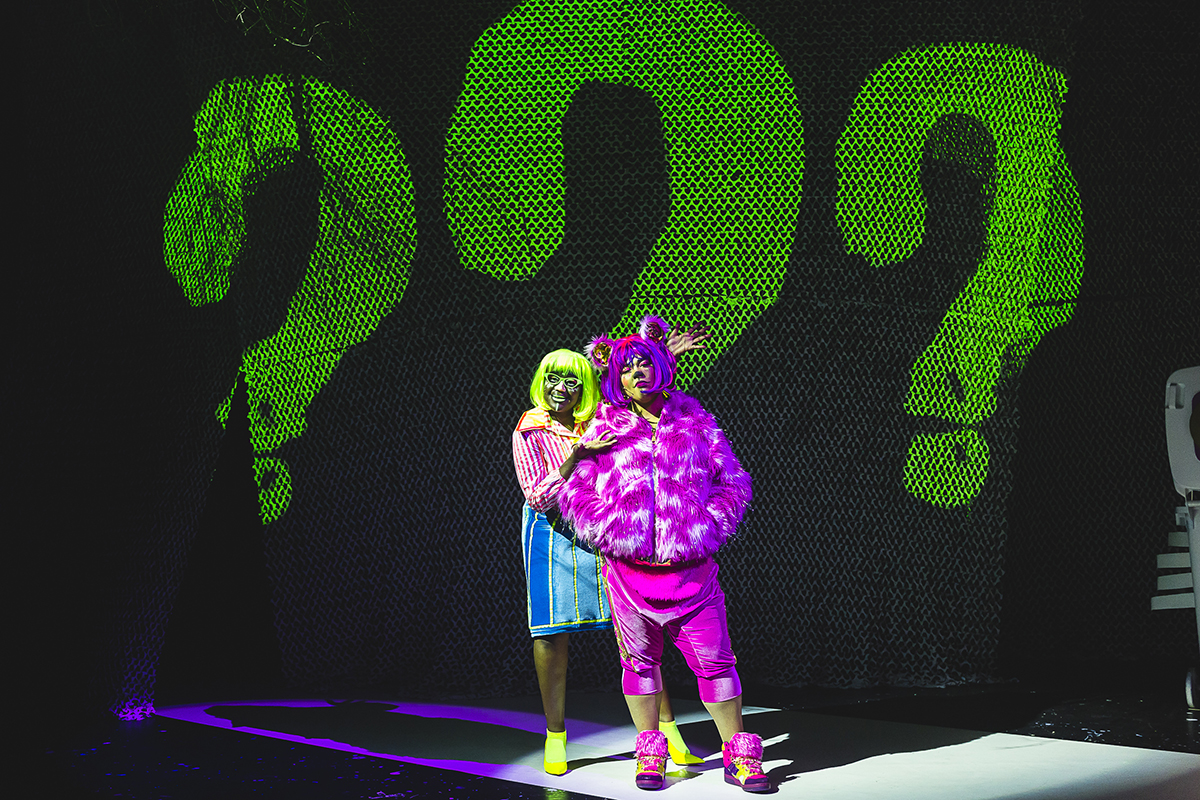

Spookers

Spookers

For cinematic eeriness, the first port of call has to be Richard Kuipers’ regular SFF sub-program Freak Me Out, with its focus on independent horror cinema. New Zealand-Australian co-production Spookers (Florian Habicht, 2017) is notable for being the first documentary to be included in this program. A comprehensive survey of the titular horror theme park, Spookers, gloriously encapsulates everything that draws people to the cult(ure) of fictional horror: Bacchic delight in imaginative excess, the liberating celebration of monstrosity and freakishness, the embrace of misfits and the opportunity to confront personal fears.

Located in the grounds of Kingseat, a former psychiatric hospital in South Auckland, Spookers is a family business whose communal ethos encircles a whole extended tribe of performers working in a variety of ghoulish roles to terrify the paying public. Broad, Tales From the Crypt-like horror archetypes are the meat and potatoes of ghost trains, and Spookers is a ghost train par excellence. The newly risen dead, weddings gone wrong, perversions of the Hippocratic oath (crazed doctors, nurses, dentists, scientists), victim-patients in straitjackets, murderers consigned to the electric chair; all combine to form a lurid tapestry from the very beginning of the film, where zombie-performers loom out of an artful cemetery brandishing tombstones inscribed with the opening credits.

With its horror movie ambience, including shots of contorted, snarling actors elaborately made-up in gore, and ominous solitary walk-throughs of the old institution, Spookers the film becomes a perfect simulacrum of Spookers the theme park experience. But beyond the frightening theatrics is a wealth of personal stories. Through interviews (more often than not in costume) and beautiful tableaux by production designer Teresa Peters, Habicht explores the motivations, fears and literal dreams of the performers and the park’s family proprietors (one of whom, in Jekyll and Hyde fashion, doubles as Mayor of Rangitikei District by day).

Crucially, given horror’s propensity to exploit mental illness as a trope, evidenced in the very direct way the theme park capitalises on Kingseat’s past incarnation, Habicht also interviews a former patient of the institution, Debra Lampshire, about her experience at the site and her thoughts on its current manifestation. She’s diplomatic but clearly unenthused. As the park’s employees reveal their own mental health struggles, however, it becomes difficult to draw a clear line between Spookers’ stigmatisation of the mentally ill as murderous psychos and its significance for staff as a supportive, cathartic outlet. Performers develop particular horror personas that allow them to gain power over their demons by embodying them. They describe Spookers as a family, somewhere they can be themselves without being judged. Huia, the chainsaw-wielding horror clown, compares it to the sense of belonging he gets from the Mormon Church.

Wolf and Sheep

Wolf and Sheep

Young Afghan director Shahrbanoo Sadat’s debut feature, Wolf and Sheep (Afghanistan/Denmark, 2016) is an ethnographic drama with elements of magic realism. Set in an unnamed village in Central Afghanistan, it offers an unhurried portrait of rural life, partly based on her own childhood experience. It begins with funeral arrangements for a man who had four young children, and unfolds in unaffected, documentary style. The film was also inspired by the unpublished diaries of Anwar Hashimi, a young shepherd who lived in Sadat’s village in the 70s; and like a diary, it captures the rhythm of events recorded daily, some dramatic, many inconsequential and repetitive, with an absence of emphasis on story arc.

There is a timelessness about the life that goes on in this high, hot, golden place, skilfully shot with hand-held camera by cinematographer Virginie Surdej on the steep mountain passes of Tajikistan, which stood in for Afghanistan for security reasons. Children, on whom the film focuses, drive flocks of sheep and goats up and down the mountainside, pausing to splash in a stream or hone their slingshot technique over the heights. Like their elders, they gossip, joke, trade colourful insults (a Central Afghan specialty, according to Sadat), stories and lore, including tales of the legendary Kashmir Wolf.

The naturalistic sound design emphasises the region’s airy isolation, with echoing goat bells, the whistling of the wind and the distant howling of wolves. Three nocturnal scenes offer a tantalising glimpse of an uncanny folkloric otherworld — yet one that’s inextricably linked to the waking life of this village, where fairytales gain potency through constant retelling.

Sadat explained during the post-screening Q&A that she wanted to make a film about Afghan life that avoided “war clichés.” There is just one hint of a wider threat to the village in the closing scene, but in keeping with the film’s deliberate historical haziness, it could emanate from any phase of the country’s occupations or civil unrest, from the Soviets to the present.

By The Time It Gets Dark

By The Time It Gets Dark

Like Wolf and Sheep, Anocha Suwichakornpong’s By the Time it Gets Dark (Thailand, 2016) is a slow and meditative experimental drama. In the opening scenes, two women arrive at a simple, spacious timber guesthouse in the Thai countryside. They are here to develop a screenplay the younger woman, a filmmaker, is writing about the older woman, a famous author and former student pro-democracy activist in the 1970s. The latter survived an infamous politically motivated atrocity in October 1976 (a real-life massacre of students at Thammasat University, commemorated annually, according to Suwichakornpong, until the military took over three years ago). The spectre of this event hangs in the air as the two conduct their interviews for the camera and otherwise politely interact.

In contrast with the violent upheaval of the author’s youth, the tranquillity is palpable in lingering scenes of the two women in their elegantly minimal dwelling, the sunlit expanse of fields and hills framed in the windows behind them. The sound is softly diegetic, a subtle whirr of crickets forming an undertone to the serenity. It’s as though you can hear the landscape breathing. Beauty is paramount in Suwichakornpong’s many figure-in-landscape passages, which usually focus on one, occasionally two, people moving through a forest in extended shots that pull the viewer into the scene.

There’s a luminous, rather pregnant quality to this first part of the film as we wait for the director-character’s ideas to gestate, and for her companion to reveal more of her past. But as quietly contemplative scenes of the two are increasingly intercut with flashbacks and dream sequences, a sense of ambiguity impinges upon linear narrative, until unexpectedly, yet languidly, we find ourselves inhabiting other characters’ lives altogether, in other locations. One is a young actor, a heartthrob who, it emerges, will take the lead role in the director’s independent film about October 1976. The other is a young woman who appears in a series of largely non-verbal roles throughout the film, sometimes coinciding with other characters.

Her various occupations — as worker at a rural café, cleaner at a city hotel, wait staff on a harbour cruise, night-clubber, Buddhist nun — offer a snapshot of contemporary Thailand, though the girl’s unsmiling presence hints at underlying discontent. Throughout these more abstract passages, the film retains its sumptuous beauty, becoming a travel experience during which you observe a small portion of someone else’s existence and try to discern their unexpressed emotions. It’s mesmerising and intriguing, but it does leave the central theme — the issue of the historic atrocity — dangling somewhat.

While a deliberate open-endedness suited the themes of Sharhbanoo Sadat’s Wolf and Sheep, in Suwichakornpong’s film it seems a decision more in service of style than meaning. Yet I wouldn’t mind stepping into the Thai director’s world again just to experience the subtle imminence she evokes in her film’s initial chapter.

–

Spookers, director Florian Habicht, 2017; Wolf and Sheep, director Shahrbanoo Sadat, 2016; By the Time it Gets Dark, director Anocha Suwichakornpong, 2016; Sydney Film Festival 2017, Festival Director Nashen Moodley, various venues, Sydney, 7-18 June

Top image credit: Wolf and Sheep

The dystopian vision of the ABC TV series Cleverman ratchets up the tension in its second season. In the real world, nervous speculation about property bubbles and a resurgence of the Global Financial Crisis has people consuming Orwellian content by the bucket-load in a frenzy of cathartic dread and vicarious release. To this time of great social and technological uncertainty, Cleverman’s Indigenous writers and producers bring a unique and unsettling perspective.

For a couple of years now, some of our old people have been muttering about apocalyptic rumblings in the landscape and the Dreaming world, of ancient things waking up or descending to leave their tracks in remote locations. Those things are out there, moving, setting things in motion that will radically change the way we live. The warning is clear: when you stop moving with country, then country will move you, in ways that are seldom gentle.

Hunter Page-Lochard as Koen West, Cleverman, promotional image courtesy ABC

These rumblings play on my mind as I struggle to navigate my urbanised Anthropocene environment littered with desperate infrastructure projects pressed like Band-Aids of concrete and steel to staunch the haemorrhaging of a fragile economy. I squeeze daily past work sites populated by an army of bored workers in hi-vis vests taking turns to hold a stop sign at the end of the mining boom, an effort to massage precarious unemployment figures. So it is with a sense of gleeful unease and anticipation that I enter the similarly gritty world of Cleverman’s second season.

As First Nations people, the creative team behind the series is familiar with apocalyptic disruption to culture and community — for them it is not an imagined future scenario, but a non-fictional reality of intergenerational trauma from dispossession. As such, there is a rich vein of lived experience and narrative involving both contemporary interventionism and past policies of genocide and removal, informing an innovative approach to the overworked dystopian genre.

The first season explored segregation and the myths of primitivism and progress through the introduction of the “hairies” of Aboriginal lore, an ancient culture uneasily labelled by the authorities as sub-human, despite their superior strength, cultural complexity and long lifespan. This recalls similarly disingenuous narratives of racial supremacy and primitivism deployed during Australia’s colonisation.

The second season boldly introduces the theme of biological genocide, referencing the many historical policies of breeding out the natives — like the Stolen Generations and the Victorian Half-Caste Act — which were the first order of business at Australia’s Federation. These efforts at extermination live today in custom if not in law, with Aboriginal people constantly being asked by settlers, ‘What percentage Aboriginal are you?’ in daily acts of micro-aggression imposing White limits on Black identity. This experience of past and present threats to Indigenous existence informs the nuanced exploration in Cleverman of a similar ‘final solution’ imposed on the hairies, expedited in the plot through high-tech genetic therapy.

This innovation is developed by a corporate villain (Iain Glen, best known as Jorah Mormont aka Sir Friendzone from Game of Thrones) who is also demanding ‘access to the Dreaming’ to weaponise arcane Indigenous knowledge. This brings to mind the intriguing notion that the psychedelic hippies of Bill Gates’ generation first conceived the idea of cyberspace through the appropriation of Indigenous ritual ‘spirit journeys’ that utilise Native American psychotropic substances like peyote.

Clarence Ryan as Jarli the Bindawu warrior, Cleverman, promotional image courtesy ABC

In comparison to the brightly lit long shots and use of open space employed in the first season, the early episodes of season two are characterised by darker, more internalised settings, close-ups, mid shots and a claustrophobic mise-en-scène. This sense of enclosure emphasises the increasing confinement and restriction imposed on the protagonists by shady corporate and government forces. The tight spaces are relieved and even jarringly juxtaposed with newly introduced wilderness settings showing the hairies’ traditional lands in inaccessible and remote mountains, with some breathtaking drone shots of waterfalls, bushland and panoramic high-ground country.

Even though there has been a discernible change of gears this season, the pace of the show is still painstakingly slow for the genre. Veteran Comic-Con nerds must be wondering, ‘When will this Cleverman Koen get clever already and start kicking some butt like a real superhero?’ Unlike the the supermen of the Marvel and DC franchises, this Indigenous hero is taking his sweet time to grow and acquire meta-human status. Although we see a non-lethal blast skill emerging (reminiscent of the “fus roh dah!” from the popular game Skyrim), it’s a little unimpressive as superpowers go. Koen also has a spirit bird who begins to guide him, and Wolverine-like powers of regeneration. The power of his law-stick is still uncertain, but is likely to end up resembling Thor’s hammer in its magical properties if the highly derivative pattern of Koen’s ability continues to develop as it has.

Cleverman’s essential premise draws on the real-life role of Clever Men within law; I find myself torn between a longing to see the traditional powers of Clever Men represented and a relief that these secrets are being kept out of the public domain.

Koen’s older brother Waruu comes more fully into his role as a “Jacky-Jacky” — a collaborator with colonising forces and institutions against his own community who facilitates exploitation in the name of Indigenous development and national harmony. This is a sensitive and explosive issue in our communities, originating with native mounted police and guides in the early days of exploration, boldly examined in Cleverman. Apart from this Uncle Tom-like transformation of Koen’s nemesis, the character development so far is fairly minimal in the transition to season two.

But black characters have always occupied an awkward space in superhero fiction, from Catwoman to Luke Cage, and I’m sure that over time character complexity will build with the awareness and comfort levels of the wider audience. In the meantime, I will be voraciously consuming every second of Cleverman season two online, and will consider it data well-spent.

–

Cleverman season two, directors Wayne Blair, Leah Purcell, writers Jane Allen, Stuart Page, Justine Juel Gillmer, Ryan Griffen, performers Hunter Lochard-Page, Iain Glen, Tasma Walton, Frances O’Connor, Deborah Mailman; ABC TV, 2017, weekly episodes from June 28

Top image credit: Hunter Page-Lochard, Cleverman, promotional image courtesy ABC

Ochre Contemporary Dance Company is presenting a new production in Perth of Mark Howett’s Good Little Soldier, which premiered at Radialsystem V Berlin in 2013 to appreciative reviews. After working in Berlin for 12 years, Howett, a Nyoongar man, returned to Perth to be appointed Ochre’s Artistic Director. His international career in lighting design, including the Adelaide Festival-Sydney Theatre Company production of The Secret River and Katya Kabanova for Seattle Opera, has expanded into video design and directing. Howett was also a founding member of renowned performance ensemble The Farm, with Gavin Webber and Grayson Millwood who collaborated on the Berlin and Perth productions of Good Little Soldier.

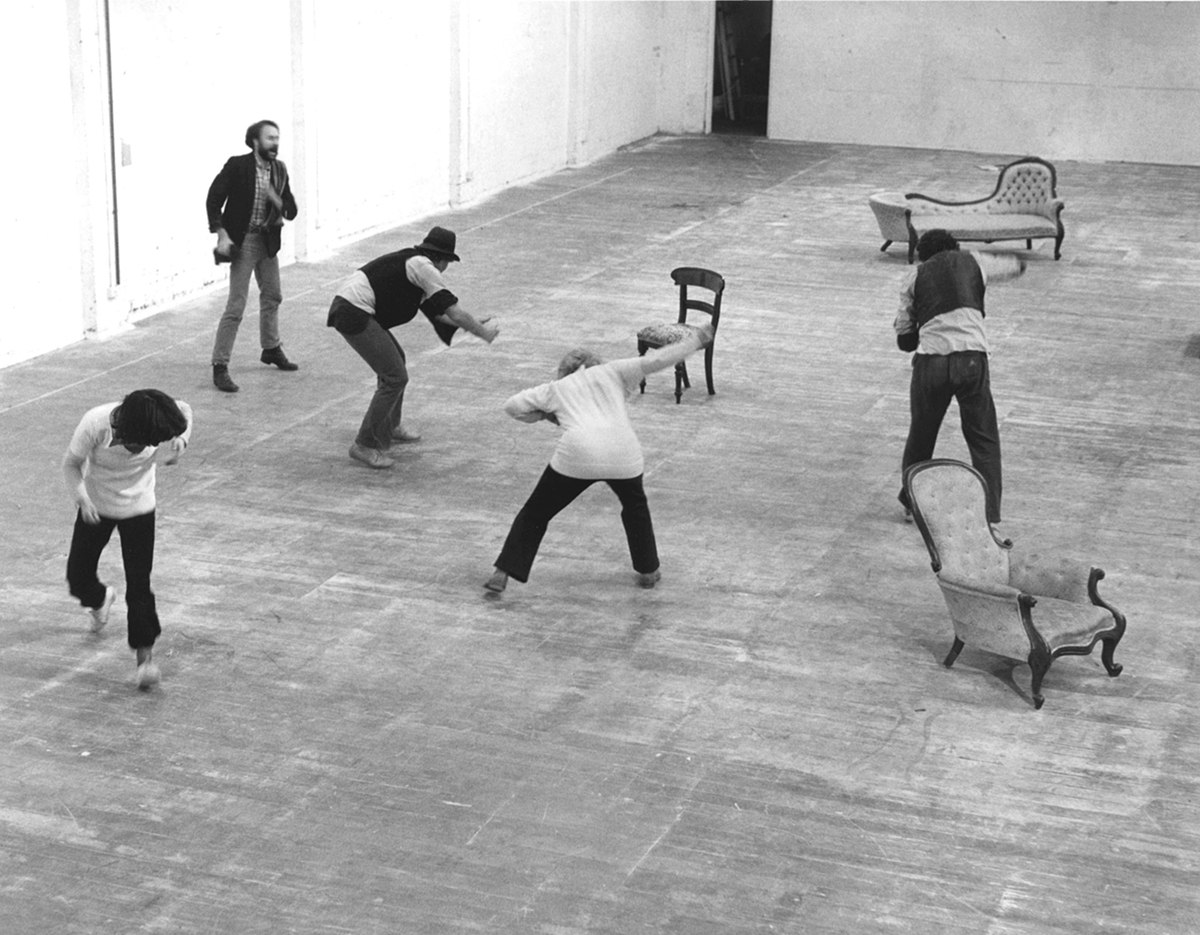

For this his second production with Ochres (the first was Kaya in 2016), Howett is revisiting a very personal subject, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which was suffered by his soldier father. Howett’s focus on the condition extends to its impact on partners and families and into the broader community. I spoke with him by phone.

What from your knowledge and experience — I understand you’ve had an instance of PTSD in your family — are the interior and exterior manifestations of the condition?

There’s the struggle of the sufferer. They don’t really want to give it out, to live it out and it manifests itself in physical symptoms, like sweating and palpitations. And hysteria is a way of dealing with trauma. We got really interested in the symptoms — like the tendency to shake or to see things as incredibly funny as a way to deal with it. Or they’ll get really remorseful and go completely internal, where they almost roll up into the foetal position.

Did you witness this yourself as a child?

I did, and at the beginning of making Good Little Soldier it was the way we got into some of the improvisations that became scenes and it was pretty cathartic for me to witness them. There were times when I found it difficult to watch. Then we started finding how some of those situations I went through were common to other families. Once we’d done consultations with organisations — like Partners of Veterans — and showings, families could come and have a say and then we fed that back into the piece. So whereas it started out with my experience, what my father’s behaviour was like, it went much more into dealing with the victims from the community’s point of view.

What was your approach to the material?

When I made this work in Berlin and it was after 12 years of living there, working as a designer and learning the German approach and their dramaturgy, I tried to get a lot of that into the way we made the work as well — a certain analytical viewpoint. I’d gone straight for the emotional in pieces I’ve made but the Germans take that away — they see it as embellishment. And they try to get to the heart of it. For example, they’ll use text in a devised work but they like to use text that the audience might know, say, a famous piece of writing about the war. When you hear those words you understand them, then you can go a step further with it in your thinking.

How do you translate the experience of PTSD, whether directly experienced by the subject or observed by family, into a stage language? There must be a leap when you’re no longer working literally?

That’s right. We try to get into it through triggers. We’ll show the incident in real time in a normal domestic scene and then use a trigger the soldier associates with the traumatic incident. That jumps us back with him — even if it’s for a few seconds — into what he’s experiencing and then back out into what is ‘normal.’

Berlin production, Good Little Soldier, photo Derek Kreckler

You’re pushing from a naturalistic scene into a heightened reality?

Yes. You get the context of what it might be like to suffer the repeating of the incident, over and over in the head. When sufferers experience it, they think they’re back there and it’s real — completely real. The trigger can be sound, it can be smell, it can be any of the senses that immediately puts them back there, even if it’s only seconds and then in the context of having to try to live a normal life when they return to be with the family. What would that be like in the middle of a normal day to suddenly be back in one of the most horrific incidents that you were involved in in the war? The family are sort of like good soldiers, ready to carry on and support him or her when they come home. They suffer it as well, because of the stress of that heightened awareness that happens within the home. You’re trying to be one step ahead of the sufferer so that they don’t experience a trigger or that you don’t cause it.

Is the trauma psychologically shared by partners and family?

I think it hits families multi-generationally. I think the suicide rate for children of veterans is higher than for veterans themselves.

You’re a Nyoongar man, you have a fellow Indigenous performer in the production and Ochre is an Indigenous and cross-cultural company. Indigenous soldiers would have suffered PTSD.

The actor Kelton Pell and I were talking about it and he said to me, “Come on, brother, all of us are suffering PTSD; it hasn’t stopped!” And that’s right. The repercussions for each generation are cumulative and really affect a whole community, let alone an individual family. That’s one of the big things we’re trying to say, that people suffering these big things unless we give them all the support we can, [trauma] can spread through the community as well. The repercussions of it, the dysfunctionality and the anguish as well for families. [Nyoongar actor, director and dancer] Ian Wilkes who is playing the ghost of a soldier is really fantastic. A really remarkable performance.

Mark Howett, photo Stefan Gosatti

Is this ghost a friend of the central figure?

Yes, and the incident is really a moral dilemma as well. Modern soldiers often have to go into domestic situations and deal with the public. There’s an even a greater dilemma for the soldier about killing. I was reading an amazing book that says only 10% of soldiers actually aim to kill. The rest aim to miss. It’s not within us to kill other people.

What’s the nature of the stage and sound design of Good Little Soldier?

The design by Bryan Woltjen is of a really isolated place that could be in the country or the city, pretty run-down, pretty dysfunctional — a bit like the family. And in the Subiaco Arts Centre theatre, we have a full 360-degree soundscape. The sound design becomes really important because noises are a very quick way of getting inside the mind of the sufferer. There’s a 21-gun salute, but it’s me doing a 21-gun salute for the innocents in the conflict. I also use video a lot in my work. I just came back from working with the Seattle Opera and filmed the countryside up there and I’m using it to help [convey traumatic] incidents as well.

And what do you hope your production will do for soldiers with PTSD and their families?

Well, obviously, beginning a conversation, building awareness that families can’t wear so much of the social cost and we have to help them in preventative ways. To the best of our ability, we must give them as much support as we can, as early as we can, so that the illness doesn’t become so prevalent and there’s a better chance of ensuring that they’re healthier people. It is about health really.

Is there anything you’d like to add about the production?

There is. The relationship with The Farm: Gavin Webber and Grayson Millwood. We’ve been long-term collaborators and I feel blessed to have worked with them and they’ve really encouraged me to develop myself as well. Part of the reason I’ve started directing is that when we were making work together in Europe, often I was the only person out front and I ended up having to do the notes on the performance. It eventually got to the stage where they’d say, “Mark, that’s enough. You’ve started directing, alright!” So, they encouraged me to go from being a lighting designer to be brave enough to conceive and develop my own work. The relationship I’ve had with them on the shows we’ve made like LAWN, Roadkill and Food Chain has been fantastic, supportive, awesome, funny, and I’m so lucky they’re part of the development of this new work. And in the same way, it’s happening in my work as a designer for Raewyn Hill, the Artistic Director of Perth’s Co3 dance company. It feels really healthy to interact with people that you’ve got history with in developing work. You know how they behave and you know their level of commitment. That they give it to you so generously is awesome.

–

Ochre Contemporary Dance Company with The Farm, Good Little Soldier, concept, direction Mark Howett, choreography, performance Grayson Millwood, Gavin Webber, Raewyn Hill, Otto Kosok, Ian Wilkes, dramaturgy Phil Thomson, design Bryan Woltjen, music Dale Couper, Matthew de la Hunty, Laurie Sinagra; Subiaco Arts Centre, Perth, 9-30 July

Top image credit: WA production, Good Little Soldier, photo Stefan Gossati

Wireless is a new self-described “polymedia” work from choreographer Lisa Wilson with co-director Paul Charlier using dance and sound to explore the ominous and intrusive nature of the technology that we carry with us daily in our smart phones. It is a bold move for a choreographer and a composer to share a directorial credit and signals that a distinctive approach to the process is being taken — cutting across discipline boundaries in the same way in which digital disruption is unravelling traditional demarcations in the broader culture. One of the most pleasurable aspects of the show is watching Charlier, a highly respected theatre and film composer and experimental musician score the show, from a table placed right in front of the audience.

Peering over Charlier’s shoulder, I watch with fascination the interplay between his computer and keyboard and the music erupting out of the phones being manipulated by the dancers onstage. The show sets the primacy of this relationship clearly with the opening image of a male dancer swiping a series of smart phones that have been pre-set on gleaming, low-set silver pedestals. This triggers the sensors within the phones onstage and as the directors’ notes indicate, all the technology used in the show is available from apps that can be downloaded onto our phones. These senors are precise enough to measure the finger taps on our screens and the quality of our sleep.

Wireless, photo Dylan Evans Photography

Onstage, the phones augment the dancers’ bodies and intentions. They are activated by the most subtle movements but crescendo with broad arcs of movement, a sonic choreography with resonance akin to a cathedral — a techno-organ that holds some of the dynamism of the performers’ bodies while still sounding like it originated from a smartphone.

The dancers (three men and a woman) move through the space playfully manipulating the phones, strapping them within body stockings on arms and legs so that they can extend and problematise the sonic choreography as they push off one another. This first section of the work mirrors the novelty of that first eager encounter that many of us had with our phones. But this initial pleasure darkens very quickly as the unremarkable rectangular black box, which has been sitting sedately on one side of the stage, only notable really for its height, opens unexpectedly. This is the first of a number of small coups de théâtre that use Bruce McKinven’s elegant set and the media elements to recontextualise how we view the interplay between bodies and technology.

The box is slid and spun across the room, dismantled and rebuilt, clambered over and used as a perch for dancers to surveille each other. In one of the most eerie sequences in the piece, the dancers add and subtract panels to and from the front of the box, their filmed and live bodies almost interchangeable. The joyous freedom of the handheld technology has been replaced by a monolithic and disturbing entrapment.

We are now inside the box, and our agency with these technologies has dissipated. The movement vocabulary darkens as the young woman is handled by the male dancers, security recordings of the city in matrix formation dominate the back screen and the black box is reassembled to become a platform shared by multiple dancers at a time.

Wireless, photo Dylan Evans Photography

Wireless provided moments of intense richness and monochrome sumptuousness that literally took my breath away, and the vernacular dynamism of Lisa Wilson’s choreography was, as always, a pleasure. Yet there was a sense of imbalance — to have only a single young female body to three men in this ominous world, particularly where that female is the focus of stalking and violence was a bleak and frightening prognosis; similarly, there was a sense at times that the technology overwhelmed the choreography, making it almost an afterthought to the central mode through which we understand our technological colonisation.

In the final and most arresting climatic sequence, one of the dancers lies prone atop the box, like a sacrifice. Meanwhile, we see footage of him projected onto the screen from the view of a rising drone while he lies in the carpark outside the theatre. Again our gaze has been distorted by the technology, and inside and outside slip into the ultimate disembodiment that we are facing with this kind of technology. Yet despite the way the body is disempowered, the grandeur and virtuosity of the image is irresistible.

–

Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Lisa Wilson Projects, Paul Charlier and Metro Arts, Wireless, director, choreographer Lisa Wilson, director, composer, software designer Paul Charlier, performers Craig Bary, Joshua Thomson, Gabriel Comerford, Storm Helmore, dramaturg Jennifer Flowers, designer Bruce McKinven, video artist Nathan Sibthorpe, lighting designer Ben (Bosco) Shaw, producer for Metro Arts Jo Thomas; Performance Space, Judith Wright Centre, Brisbane, 15-17 June

Top image credit: Wireless, photo Dylan Evans Photography

Entering Occasions is like walking into a party where you don’t know anyone. You’re in a gallery, but there’s no work on the walls. There’s music but you’re supposed to just sit around and have a drink, it seems. Oh dear, how awkward. But hang on. The many small trees and pot-plants arranged in the space are perhaps not merely to create a ‘look.’ There’s a strong scent coming off them, like pine sap mixed with fresh mown grass and something indefinable, perhaps metallic. Then Isabel Lewis, who’s been having a conversation with a few people in the middle of the room, begins to move around with a black box the size of a speaker. As she explains, this is actually the source of the strange odour, not the plants. The aroma has been composed by Lewis and her collaborator, Norwegian chemist Sissel Tolaas, for a specific reason. It’s entirely abstract, intended to encapsulate the idea of “intellectuality” or the “culture of the mind.” It’s a thought experiment that you can contemplate through the nostrils.

Having made sure everyone present has had a decent whiff of intellectuality, Lewis, a small energetic woman wearing a jumpsuit and sneakers and speaking with an American accent, moves around the space, talking into a microphone. Born in the Dominican Republic, Lewis grew up in Florida and now lives in Berlin. She canvasses opinions on the scent. She elaborates on her interest in the science of smell. She points out that there’s something dishonest and disturbing about using a “nice” smell to mask something horrible. From here she begins to riff on ideas around sensitivity and perception. For example, what if we could feel the energy, the ‘vibe’ of inanimate objects, in the same way we can with animals? What if we possess sensory capabilities of which we’re not aware?

Isabel Lewis, Occasion, photo Lou Conboy

In short, Lewis embarks on a 20-minute philosophical filibuster, a lecture of sorts. Just when it begins to seem like this is all the work will be, it changes — mid-sentence. She turns a knob on the audio mixer and an effect causes her voice to repeat, exaggerating her words, making them part of the music. A slow beat takes over and she begins to dance, exploring the space with angular, flowing movements, holding court in a new way that’s also a continuation. After a while, she explores space even with her microphone, directing it into the box that contains the artificial scent. Intellectuality, as it turns out, sounds like a bass hum, and suddenly there’s a buzz going through the floor and up into the wooden boxes we’re sitting on. We are all now together feeling the vibe of inanimate objects. Drawing on her skills in dance, DJing and composition, as well as her studies in philosophy and literary criticism, Isabel Lewis has accomplished a poetic parlour trick of sorts. And she’s not finished yet.

Occasions lasted for three hours on the evening I attended. I didn’t stay for it all, but long enough to get the idea, I think. That’s the danger of performance art, knowing when to stay and when to go. Then again, you could be at the world’s best party and still choose the wrong time to go to the bathroom, so why not relax and go with the flow? Lewis and collaborators (curator Scot Cotterell and designer Juan Chacón) have created a welcoming, accessible and invigorating experience. Worrying too much about how best to partake of it would be missing the point.

What’s most notable is Isabel Lewis’ ability to blur the lines between artist’s talk, performance, installation and social gathering. And after all, why should performance be separated from ordinary life? Or art from its analysis? Lewis explains at one point that children are particularly appreciative of “diversity” in scents. The more rich and layered, the more fascinated the young become. Perhaps it’s only as adults that we learn to prefer things to be simplified, to be put into neat categories so we won’t get confused.

–

Contemporary Art Tasmania & Dark Mofo 2017: Occasions, host Isabel Lewis, curator Scot Cotterell, designer Juan Chacón; Contemporary Art Tasmania, 7-11 June

Top image credit: Isabel Lewis, Occasions, photo Lou Conboy

Anyone who’s been stuck on central traffic arteries like Reforma and Insurgentes in peak hour might attest to Mexico City’s special relationship with sound. Indeed, sound has a distinct place in the city’s creative life and cultural production, which includes festivals of sound art like El Nicho, the sound art collection of the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo (currently on display until the end of July), and much-loved institutions like the Fonteca Nacional, a patrimonial record of the country’s sound cultures housed in the former home of author Octavio Paz.

In two ongoing projects, Mexico City artists are working with sound, streaming and radio waves to explore questions of curation, performance, political discourse, memory and public assembly. They are Escuchatorio, “a listening act” and #Todas Las Canciones Son Nuestras, “a collective memory exercise.” I spoke with artist and producer Juanpablo Avendaño Avila who is involved in both projects.

“Escuchatorio is a platform that seeks to compile sounds and audio files captured by people,” says Juanpablo. “We make a call to the general public to send us these sounds around a particular theme. Then we collect them and launch them on a symbolic date. With the accumulation of sounds combined with the symbolism of the date, the exercise becomes a kind of sound performance in which many people gather to listen — almost as a kind of meeting, a collective gathering about something that all those people care about.”

Todas las Canciones advertising

EscuchatorioProtesta

The first such event, EscuchatorioProtesta, took place on 26 September, 2015, a date chosen for the first anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from the teachers’ college of Ayotzinapa in the state of Guerrero. Participants were invited to submit, via the Escuchatorio platform and the WhatsApp messenger app, sound files of social protest. A total of 435 submissions were filed and then played over 43 continuous hours. The signal was boosted by the social media hashtags, but also with the collaboration of 36 radio stations, based all over the world — from Radio IBERO in Mexico City to Phaune Radio in France to Radio Ambulante and Vocalo Radio in the USA. The audiences of these stations were also invited to submit material, adding a multilingual, polyphonic ambience to the event conceived and produced by Juanpablo with Diego Aguirre and Felix Blune, with contributions from many others in the communities around art, sound and radio in Mexico City.

Nearly two years on, the importance of this event seems amplified. Just this week the parents of the missing 43 took their caravan of protest to the state of Quintana Roo (home to popular tourist spots like Cancun and Playa del Carmen), still craving answers in the wake of investigations that have found drug cartel, police and government complicity in the kidnapping, and the remains of two of the students.

Juanpablo Avendaño

The next Escuchatorio event is currently being planned for 16 September this year. This day, known as El Grito de la Independencia, marks the first day of Mexico’s annual independence celebrations. “El Grito” is a cry, or a shout, in this case believed to be delivered by Miguel Hidalgo, who catalysed the revolt against the Spanish colonists in 1810 with a speech on the steps of the church he led in Guanajuato, north of Mexico City.

“We are working with the idea of silence, as a counter-position to that of the shout,” says Juanpablo. “At the same time, we want to consider how the idea of independence itself has been devalued in Mexico — so we will be highlighting a kind of destructive tension between silence and grito, through the silencing of the signals of independence.” To be sure, markers of political independence such as state accountability and electoral oversight are often found wanting in Mexico. The Ayotzinapa case offers a demonstration of this impunity, a particularly potent example of the collapse of the people’s sovereignty.

Listen to the Escuchatorio camina [walk] held 1 May, 2016. In English the words are: “Escuchatorio camina — this is a call to the walkers — to your feet, to your ears; walk to resist, walk to hang out, walk to rediscover, walk to slow down… send your sounds by 30 April.”

TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras

#TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras (“All the songs are ours”) centres on the importance of memory and also functions as a re-routing of the political through the collaborative act of listening. Specifically, in Juanpablo’s words, “this project seeks to compile and generate energy around sound files — mainly music, usually songs — that have affected or formed in some significant part our idea of the political.”

“The call-out for material consists of some simple questions, such as which song you identify with your political stance and which song you identify with a significant historical moment; and then we ask you to share the name of the song [a sound, a melody] and some brief words on why and how you remember it in this way.”

Conceived in 2016 by Maria Cerdá Acebron and produced and implemented by Maria in conjunction with Juanpablo, submissions (via the online platform, or WhatsApp) to #TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras are not always explicitly political; perhaps because participants are invited to consider songs and sounds that invoke, through memory, the development of one’s personal political outlook as opposed to those who might have a specific political agenda. One example is the submission of “La canción de la culebra” (“The song of the snake”), a banda track associated with the assassination of a politician who was a candidate for the presidency in 1994. It is this song that was playing at a public rally for politician Luis Donaldo Colosio when he was shot dead, apparently by a hitman. There is video footage (which had wide public coverage) of the shooting, wherein one can hear the song very clearly, and where the lyrics (eg “beware the snake”) rather spookily keep narrative time with the advance of Colosio’s assassin. As a submission to #TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras, says Juanpablo, “’La canción de la culebra’ is not so much political as representative.” That is, in public memory the song is symbolic of a significant event concerning a prominent politician running for the highest office of leadership in Mexico in a year of particular political turmoil for the country — 1994 was also the year of the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas on January 1, a date that also marked the commencement of the North America Free Trade Agreement between the US and Mexico.

“La canción de la culebra” also has a longer history as a song in the genre of banda, a very prominent musical form in Mexico with varied symbolic and political associations of its own. Regarding those who have submitted this track to #TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras, we know that the song has mattered politically, but, given the dispersed and multi-threaded nature of its associations, indeed much like the nature of memory itself, we can only guess at how.

As projects, Escuchatorio and #TodasLasCancionesSonNuestras sit outside “the circuit” of Mexico City’s long and strong tradition of sound art and culture, Juanpablo says. Indeed, it is clear that these artists and producers are bending the circuits of sound production in this noisy city, where there are plenty of issues and stories in search of amplification and orchestration.

–

Top image credit: Escuchatorio Protesta showing faces of the Ayotzinapa disappeared students

Reason for travelling

I first came to Tokyo by accident on the way to Canada. That was in 2006. Since then I have visited more or less every year — for the culture, the food, the people, the art, the general ‘atmos’ and the ongoing discoveries that this city affords.

A sensory vortex

Before I came, I imagined Tokyo to be teeming with people, hedged in by high-rise buildings, rushing around, packed in like sardines. Many trips later, I find this city to be a sensory vortex, a perceptual oasis in the rush of my own life, affording the opportunity to sample and explore a rich and complex culture. Home to some 20 million, Tokyo consists of many sub-spaces, urban villages, each with its own atmosphere, able to modulate a kind of slowness within. I have been here more than a dozen times, and each time find a new pocket to explore, a new gallery, restaurant, side street, whatever. I could come 100 times and the story would be the same.

Movement, respect, Zen

Movement is carefully mapped here, the body marshalled for exactitude. I really like the fact that people bow to each other. I was at a screening of a dance program, shown as part of the 2017 Multiple Futures exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (TOP), where the curator of the screening introduced herself; the entire audience bowed in their seats. People bow in shops, to say hello, goodbye, to introduce themselves, to show respect. It’s nice.

Purchases are artfully wrapped, food is exquisitely prepared, details are important in everyday life, at least within the public sphere. There is probably a downside to all this attention to detail, an imperative to conform, perhaps. You can find old coffee shops (kissaten) where brews are made under laboratory conditions. I remarked upon this to a friend once, impressed by the care taken. He suggested that there is a ritual dimension to everyday life, a more or less unbroken feudalism extending into the present that calls for a certain absorption within, and commitment to, action — which we might call Zen.

For refreshment…

Food is a delight in this city. I cannot emphasise this enough! There are small restaurants, where you buy tickets from a machine for any number of noodle variations, fresh soba, delectable stock, all under $10. Or you can have a seasonal, degustation meal (Kaiseki) with 10 courses, each in signature dishes for much more. Every visit I walk into new places off the street, there are countless options. The Japanese love French cooking and there are many French restaurants and patisseries with the names of well-known French chefs. All the department stores have basement food halls (called depatchicka). These offer an amazing array of cooked dishes, food from around the world, raw ingredients and cakes, loads of cakes. The Japanese love a seasonal theme. In Autumn, it’s chestnut, in Spring, it’s cherry blossom. And there’s Halloween and Valentine’s Day. A great deal of attention is paid to the seasons. Exquisite flower arrangements in high-end buildings reflect the seasonal moment. Food embraces the shifting supply of produce.

Moving about…

Getting around is extremely easy. Tokyo Metro has numerous lines, well labelled, that criss-cross the city. Millions of people use public transport here — the trains fill up, move on, new ones immediately arrive, fill up and so on. To observe this from outside the aim to get from A to B is to witness an awesome system at work, that sets a time and sticks to it. Public transport is privatised, like many services and institutions. Consequently, they all stop close to midnight — a major pain in the arse for anyone who likes to stay up late. I have no idea what people do (other than take taxis or hole up in capsule hotels). Maybe that’s why so many people live in the area of Shibuya, home to a great deal of youth culture nightlife.

For culture…

Although there are a few national and city museums, many more are privately owned and therefore have to be researched. A lesser known favourite of mine is the Ota Memorial Museum of Art in Harajuku. It features changing displays of Japanese wood block prints (ukiyo-e). These are wonderful, giving a sense of life during the Edo period in old Tokyo, or of the arts, particularly Kabuki theatre. There are many images of famous Kabuki actors, performing familiar tales. These are superb, fleshed out in indigo, salmon pink and aquamarine, with flowing black lines. Each month will have a different theme, selected from the thousands of woodblocks in the collection.

The Nezu Museum in Aoyama is exquisite, from its modernist Japanese housing to its fine collection of ceramics, to its finely tuned garden. The approach to the museum follows a long pathway, flanked by a wall of bamboo, and a river of stones. Its internal spaciousness creates an aura that enhances the appearance of each individual item.

People often write about the cosplay youth culture that plays out in Harajuku and Yoyogi Park, where people dress up as particular characters or identities and roam the streets together. On the weekend, you will see young men and women rolling suitcases crammed with clothes and makeup, ready for a day’s outing. And yet, I have heard it claimed that this cultural fiesta is ebbing. When I first visited Tokyo more than a decade ago, young women would be immaculately made up, their nails artworks in miniature, complemented by high heels and skirts. Now, female dress codes are much more relaxed, often featuring jeans and sneakers. Times change. The 2020 Olympic Games is bound to institute more change in the social landscape of the city.

People work long hours here. As a tourist, I do not see the ways in which the domestic sphere is organised and the home managed, what sexual politics arise and how personal space is negotiated. Having just started to learn Japanese, however, I am beginning to have a sense of certain differences that are reflected in the arrangement of words, their content and style. Raising these issues, I realise the very particular perspective that tourism affords. Inevitably framed by its limits, I am nonetheless thoroughly indebted to this urban culture for furnishing me with so many delights.

Places to visit

Museums and shrines

Ota Memorial Museum of Art, Harajuku

National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, Takebashi

Tokyo National Museum, Ueno

Meiji shrine, Meiji-Jingumae

Sensoji temple, Asakusa

Mori Art Museum, Rippongi

Nezu Museum, Minami-Aoyama

Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (TOP), Ebisu

Ghibli Museum, Mitaka

Museum of Contemporary Art (MOT), Kotu-Ku

Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, Meguro

Performance

Kabukiza Theatre, Ginza

Noh National Theatre, Chiyoda-ku

Areas and shopping

Omoto-Sando, Aoyama, Harajuku (people, shopping)

Kiddyland, Jingumae

Tsujiki fish market and outer market (for food, seaweed, tea, miso, umeboshi, pickles, sushi/sashimi eateries)

Takashimaya (food halls)

Isetan, Shinjuku (fashion, food halls)

Shibuya 109 (fashion)

Pierre Hermé, La Porte Aoyama (cakes, desserts)

Golden Gai, Shinjuku (tiny bars)

Loft, Shibuya (funky paper, stationery)

Itoya, Ginza (classical paper, stationery)

–

Top image credit: Tokyo, photo by Philipa Rothfield

In 1998, when it seemed like it was just beginning, tech visionary Nicholas Negroponte declared the digital revolution over. This did not mean the end of computational technology, but that in the networked world it had become so pervasive as to cease being remarkable. Perceptions toward technologies had changed as the digital infiltrated so many aspects of everyday life. Since then there has been an increasing intermingling of digital and analogue and tentacle-like extension of the digital into realms beyond the screen. Amy Marjoram, curator of the Warp exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre, observes some of the effects of this entanglement, writing in the exhibition catalogue, “When we exist so much online, trace residue from this existence is everywhere in our lives.”

Certain pundits describe this condition as “post-digital.” Just as postmodernism was perceived as being not about the absence of modernity, but rather a continuation and splintering of its effects, the post-digital is a reconciling of the effects of the digital with the existing world. Attendant to this, and especially in the arts, is an increasing drive to humanise technologies, a concern with being human in a networked world with technology as integral. Echoing such ideas in the curation of Warp, Marjoram writes, “This exhibition is about the cohabitation of the digital and physical realms, and the reality and mirages within both.” As part of the 20th anniversary of the Revelation Perth International Film Festival, Warp tackles our digital present with works that engage with the complexities of its manifestations, from the mundane to the provocative.

Call of the Wild, 2013, Michael Meneghetti, WARP, Fremantle Arts Centre, photo Jessica Wyld

Across two rooms and a corridor, Warp presents new video works by four Western Australian and four Victorian artists. The first room is dominated by a large scale projection by Michael Meneghetti (VIC) titled Chiamata del Selvaggio/Call of the Wild (2017). Like an awkward seal at the edge of the water, a person clad in a head-to-toe black wetsuit with flippers, flops along a seaside. If not an earnest grasp at transhuman embodiment, this absurd scene is certainly reminiscent of the bizarre expressions of humanity that you might stumble across in online fetish videos.

At the opposite end of the room is Constant Elation (2017) by Tom Blake (WA). A sheer curtain cordons off part of the wall on which videos are screened on a cluster of mobile phones. The scenes playing out all revolve around the theme of plane travel: red wine quivering in a plastic cup, the shadow of a plane glimpsed on the ground, views outside the window and the suggestion of states of jet lag. Over the course of the day the screens gradually die off as phone battery life is exhausted. This is part of the work, a commentary on the tenuousness of mobile technologies, their failings.

Lou Hubbard (VIC) has a curious work in this room titled Tap Me (2008). An elderly woman lady sings in dulcet tones but all we see is her finger repeatedly tapping a touch-sensitive lamp and changing its output. This simple and somehow melancholic gesture is loaded with meanings. It speaks of a gaping generational divide and the reality that for digital natives this gesture is immediately associated with repetitively and mindlessly tapping through screen content.

Video still, Hospital Landscapes, Georgie Mattingley, WARP, courtesy the artist and Fremantle Arts Centre

Part of the lure of the digital is its ability to infinitely distract; beyond fleshy reality precious time dissolves into screens. This idea is implied on a monitor in the hallway screening Georgie Mattingley’s Hospital Landscapes (VIC, 2016). It cycles through still images of paradisiacal scenes as wall murals or on posters in otherwise clinical hospital environments. These landscapes are meaningless distractions like so many of the superficialities encountered online. They silently rupture the homogeneity of the sanitised space, but belie this aim by simply fading into the background, as unremarkable.

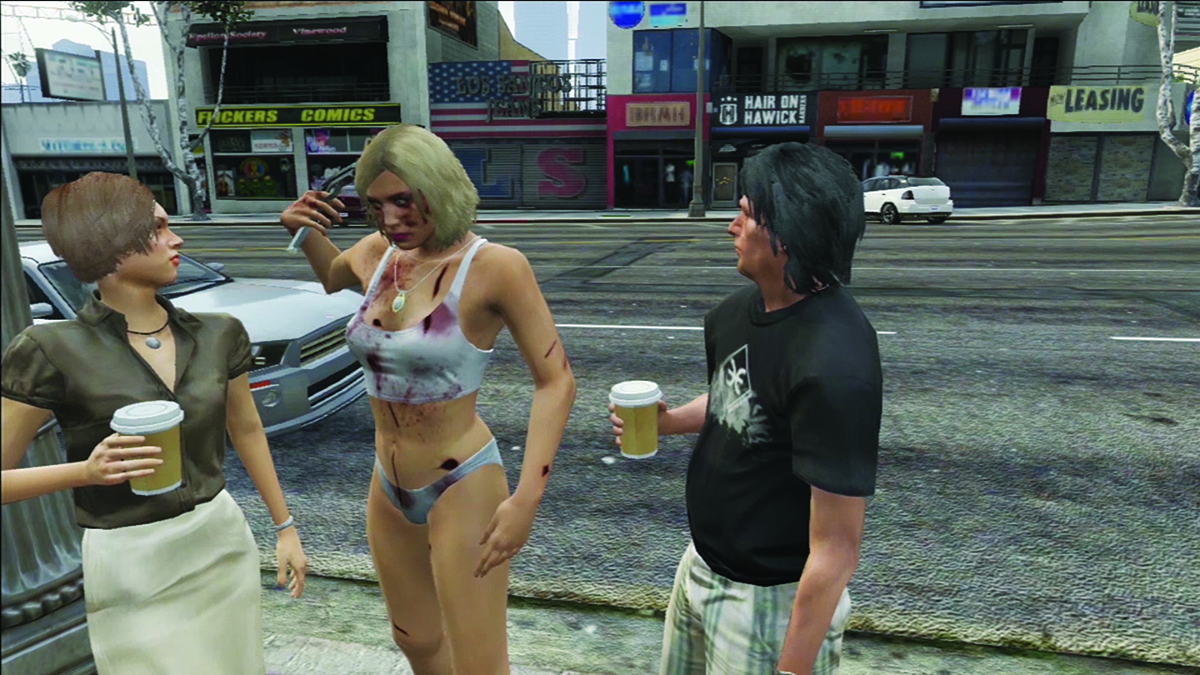

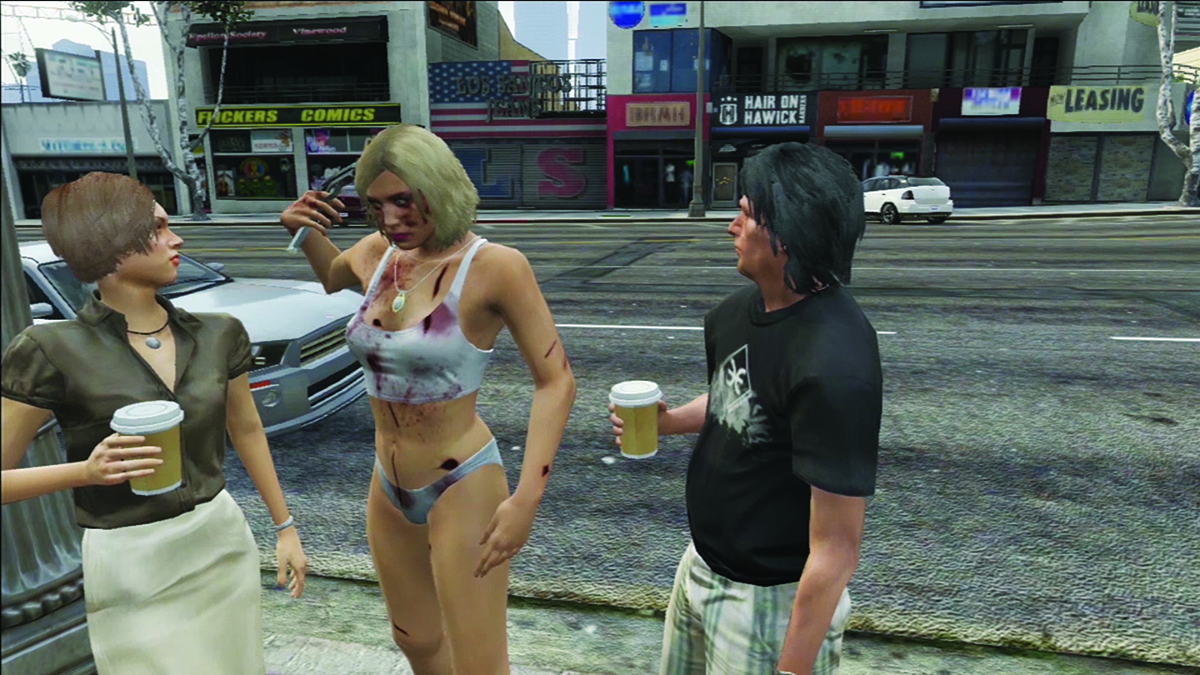

The next room is an auditory assault with the sound of a gun being fired ad nauseum. The source is 99 Problems (WASTED) (2014) by Georgie Roxby Smith (VIC). In an online video game intervention into Grand Theft Auto V, a bikini-clad, blood splattered female avatar repeatedly shoots herself in the head in various urban contexts. Marjoram writes that this exhibition will “gently puncture the apparent seamlessness of the networked world,” and while this piece presents a violent puncture in otherwise calm game moments, it is also self-referential to the genre and its gratuitous violence.

99 Problems (WASTED), 2014, Georgie Roxby Smith, WARP, courtesy the artist and Fremantle Arts Centre

It’s a relief, perhaps, to turn to Andrew Varano’s Tracking Shot (Autumn) (WA, 2017). At the end of two parallel bench seats is a screen on the floor, angled upwards and displaying a tracking shot of the ceiling of a room from the perspective of the floor. The camera pans, showing us a lighting track and the underside of couches. This is like a portal into the domestic space beyond the screen and we are reminded of the bench seats on which we sit, embodied.

A similar perspective is granted in Dale Buckley’s From where you’d rather be (WA, 2017). Here the camera gazes up at and smoothly pans along tree foliage; only the vision is filtered and crunchy. It is as though we are granted robot vision and this recalls early computer scientist Alan Turing’s suggestion that artificial intelligence could develop from robots roaming the countryside and learning from the physical environment.

Aptly then, Ellen Broadhurst (WA) suggests the spill of the digital into the physical, or their post-digital hybridisation, in two works where videos are embedded within vomitus, bulging landscapes of expanding foam. In John Oldham’s Phony Waterfall (2016) a log plinth contains the foamy landscape, embellishing it with artificial fern foliage. On the screen we see washed out footage of a hidden waterfall in John Oldham Park in inner city Perth. There’s a suggestion here of a loss of the real; a phony creature swims in the water and although it’s in a real place, it is also housed within an entirely artificial landscape.

In “What is Post-Digital?” media theorist Florian Cramer argues that the post-digital “refers to a state in which the disruption brought upon by digital information technology has already occurred.” Warp makes it look as though we are caught up in the aftermath of this disruption, in tentacles of the digital in a kind of eternal return, like the avatar who keeps shooting herself and coming back, there is no escape.

–

Warp, curator Amy Marjoram, artists Tom Blake, Ellen Broadhurst, Dale Buckley, Lou Hubbard, Georgie Mattingley, Michael Meneghetti, Georgie Roxby Smith, Andrew Varano; Fremantle Arts Centre, 27 May-16 July

Top image credit: Video still, The Ship That Never Sank, 2017, Ellen Broadhurst, WARP, Fremantle Arts Centre

Featuring commissioned works from seven Australian female composers, Decibel’s warm, witty and incisively political new music tribute to former Prime Minister Julia Gillard will play at Monash University on 20 July and Brisbane’s Metro Arts on 13 and 14 July. The concert premiered in Sydney, 8 November, 2014 and was repeated in Perth on 20 April, 2015.

After Julia’s composers — ranging across sound art, experimental, contemporay classical and theatrical scoring — are Gail Priest, Thembi Soddell, Cathy Milliken, Michaela Davies, Kate Moore, Andrée Greenwell (with writer Hilary Bell) and Cat Hope, Decibel’s Artistic Director and commissioner and organiser of the event.

Decibel, After Julia concert, photo Lucy Parakhina

Gillard was present for the premiere with her parents, and although admitting to limited experience of contemporary classical music, clearly enjoyed the empathy and sense of occasion, although hearing herself and the vicious riffing of her opponents made musical might well have been disturbing, as it was for others of us in the audience.