Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

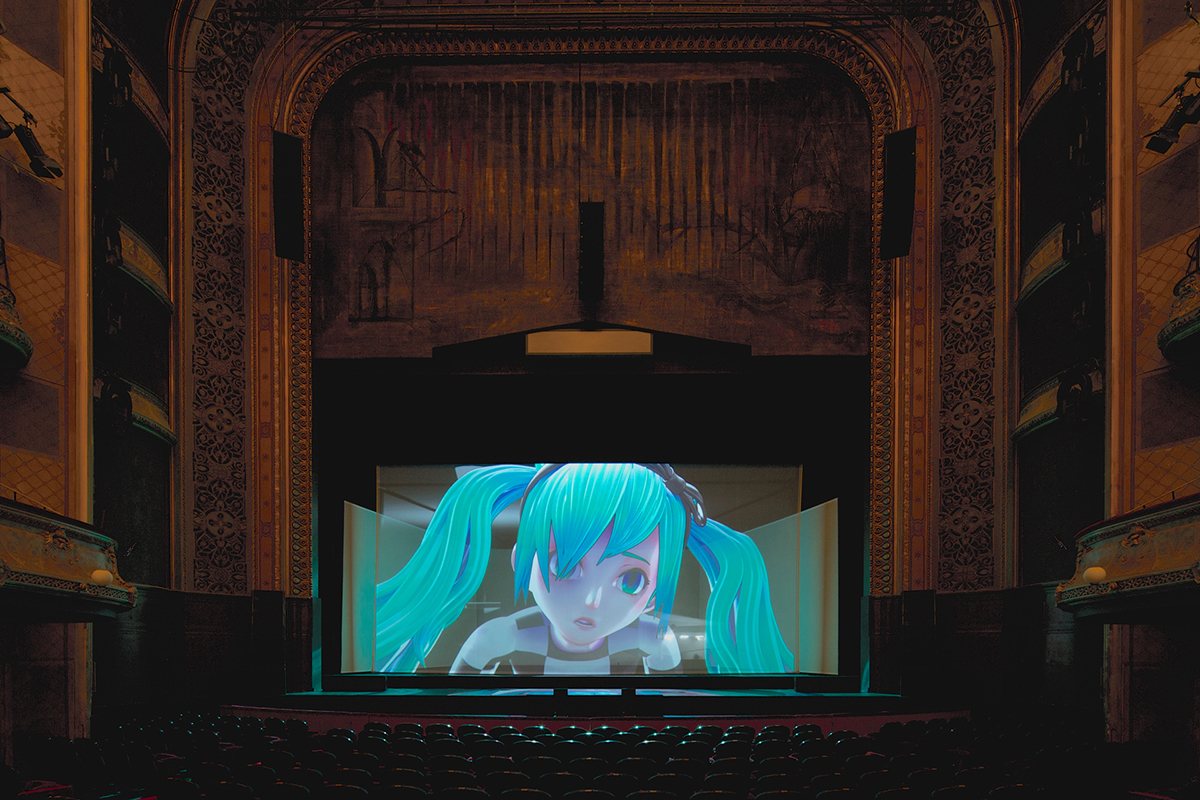

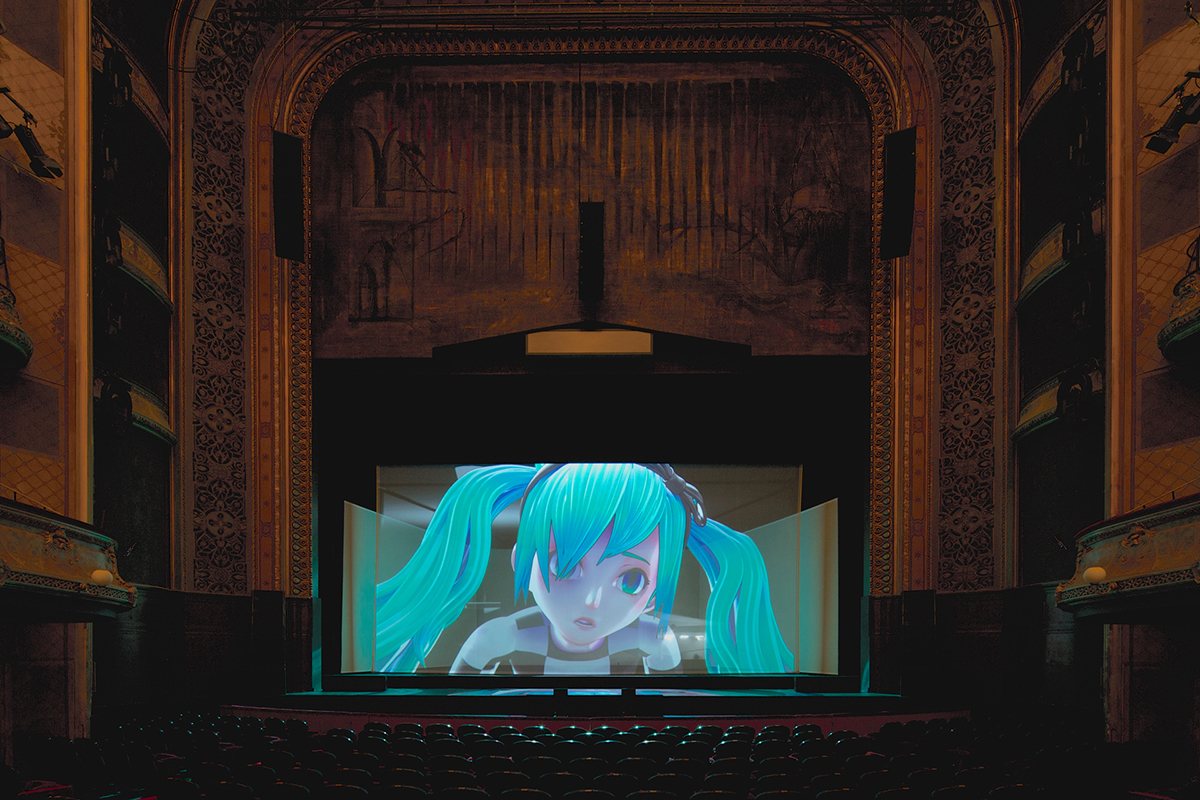

Adelaide’s OzAsia Festival proves more than ever to be vitally enticing with a program featuring great artists and works unfamiliar to Australian audiences. This week in an interview with Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell we focus on key performance works including those from Japan by theatre-maker Kuro Tanino, conjuring haunting inner worlds, and leading composer and experimentalist Keiichiro Shibuya, probing the mind of a virtual performer, the massively popular Miku Hatsune (image above) in The End, an opera he’s written for her. An acclaimed five-hour play from Singapore’s W!LD RICE courses through 100 years of the city state’s history. Next week we look at inventive Asian-Australian collaborations and, later, the festival’s fascinating visual arts showings. As Peter Dutton takes control of state power and foreshadows the end of compulsory voting with his referendum by postal vote — in the age of the internet! — OzAsia invites a greater sense of distance from what it is to be, often all too lazily, Australian. Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: The End, Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, photo Kenshu Shintsubo courtesy OzAsia 2017

If there has ever been a necessary moment for Australians to be ‘taken out of ourselves,’ to evaluate our cultural and political place in the world as geopolitical tectonic plates shift us away from the US, it is now. Once ‘outside’ we can open up to and appreciate cultures substantially different from our own, look back at ourselves and acknowledge the art growing here that tells us how Asian-Australian our culture has become, alongside and entwined with our European and Indigenous heritages. With an intensive program, at once accessible and provocative, Adelaide’s annual OzAsia Festival continues to temporarily relocate and enduringly reshape our collective imagination with intensive and seductive programming.

When we meet in Sydney prior to the launch of the 2017 program, I ask OzAsia’s Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell about the progression of his programming over his three festivals since 2015. He tells me that after “breaking down the fourth wall” with immersive contemporary Asian works (including visual and performance art) in his first festival, in his second he focused on works that commented on their countries of origin (including the strange cultural and economic relations between America, Japan and Korea in Toshiki Okada’s wonderfully absurdist God Bless Baseball), “along with a brushstroke picture of the city/rural divide” (as in the wildly funny and socially critical Chinese production Two Dogs, an exemplar of the merging of traditional and modern popular performance).

In his third festival, Mitchell says he’s “going in deeper with a large focus on very personal and intimate stories told from Asia and with more Asian-Australian collaborations, in the arcs of dance as well as in theatre.” As our conversation continues, it becomes clear that the ‘personal’ will be framed within mythology, history and gender as will a focus on artists who are setting the agenda for furthering 21st century Asian and global culture.

Next week we’ll survey collaborative Australian and other works in the festival’s program and, shortly after, the visual arts component. This week Mitchell and I focus on the major theatre and music components.

Until the Lions, Akram Khan Company, photo Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy OzAsia 2017

Akram Khan Company, Until the Lions

At first glance, British choreographer Akram Khan’s acclaimed Until the Lions, a dance adaptation of a story from the Mahabharata, seems an unlikely ‘personal’ tale. Mitchell explains, “It is a big work, with a big set, but it’s a particularly individual story. The creators, Khan and poet Karthika Nair, have focused on a story they convey from a female perspective about a princess, Amba, who is abducted by a general, Bheeshma, and she seeks venegeance.” Nair had gathered stories about often unacknowledged female characters from the Mahabharata in her book of poems Until the Lions, which became the title of her collaboration with Khan. In an unusual twist, Amba kills herself, is reborn and changes gender to defeat Bheeshma. Nair has explained the title: it’s based on an African saying about who gets to tell the story after the hunt — usually the hunter; but the tale is not properly told until the lions speak; as it should be for the women in the male-dominated Mahabharata.

Although British reviewers have praised the work for its adroit abstraction and use of symbolism, Mitchell says, “dance theatre is such a loose term, but Until the Lions is a narrative told through dance in 55 minutes. “As with a play, “you need to watch and decode to understand.” A YouTube trailer offers glimpses of an engaging blend of the literal and its abstraction, particularly in fight scenes.

Recalling Mother

Mitchell describes Recalling Mother as conversational performance but also as another very physically expressive work. Singaporeans Claire Wong and Noorlinah Mohamed are friends who explore their relationships with their non-English speaking Cantonese and Malay mothers, taking turns to play each other’s mother in mother-daughter dialogues. Mitchell tells me that when the work was first performed almost 12 years ago, the emphasis was on comedy and the language and culture-clash tensions “between tradition and Singapore’s slightly hybridised Western identity. The humour is still there, but the artists don’t remount the play so much as recreate it now that one of the mothers has dementia and the role of carer and a sense of mortality have entered and intensified the sentiment. The show runs for 75 minutes but with a Q&A which the artists see as part of it, because they feel audience members need to debrief about their own relationships with their mothers.”

In an interview, Noorlinah Mohamed said of Recalling Mother, “It is perhaps the first and only theatrical project, that when restaged, is always revisited as a new creation. The work is a living durational performance where life and art parallel and inform each other.”

The End, Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, photo Kenshu Shintsubo courtesy OzAsia 2017

Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid Opera: The End

The sense of the personal might seem to evaporate when contemplating two works by a Japanese artist which feature non-human performers: one with a vocaloid (think singer + android) and a robot. Of Asian artists setting the agenda in performance, Mitchell sees Japan’s Keiichiro Shibuya, “with his bold sense of provocation,” as the standout exemplar. He has created The End, an opera for theatre without live singers or an orchestra for virtual pop idol Hatsune Miku. Mitchell says, “she is one of the biggest pop stars in the world. She has some 100,000 pop songs about teen love and relationship breakups, composed by professional teams but also by hardcore fans via purchased software. Shibuya had been a fan and when his wife, a leading fashion designer, died and he spiralled into depression, he latched onto thinking about the nature of death and how Miku will never die. He thought, ‘What if I go into her psyche and find out who this vocaloid is, loved by the world?’ So he asked the novelist, playwright and Artistic Director of chelfitsch, Toshiki Okada, to write the libretto and approached Louis Vuitton to design Miku’s outfits for a giant opera. It’s the most elaborate of her set-ups for an appearance and involves four screens and a mini-screen behind which Shibuya plays the music live.”

Mitchell notes that “When The End debuted Miku’s fans turned out: they were nervous, keen to support her doing opera, hoping she’d last the distance, but had faith in her and were very excited to see her dressed by Vuitton. It went to Europe last year, a bit outside her realm, but created a fusion of arts lovers and fans.” He does believe The End “has to be a dividing piece in terms of the operatic voice. However, the score and the libretto have all the hallmarks of great operatic tragedy and self-insight. At a time of the Australian Government review of opera, a decline in audience numbers and the large cost of the subsidy involved, we need to think about the artform and let it evolve; this work points a way.”

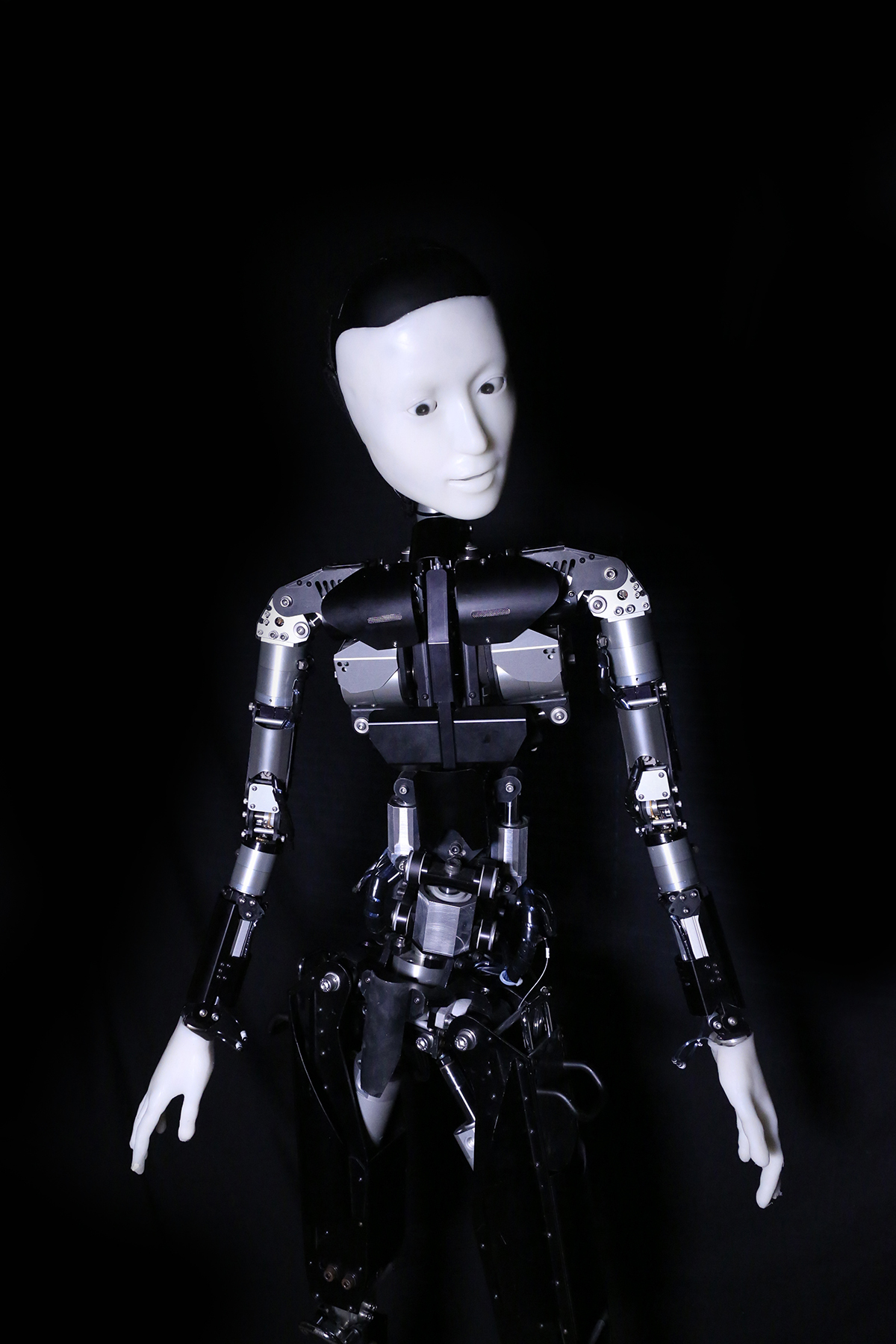

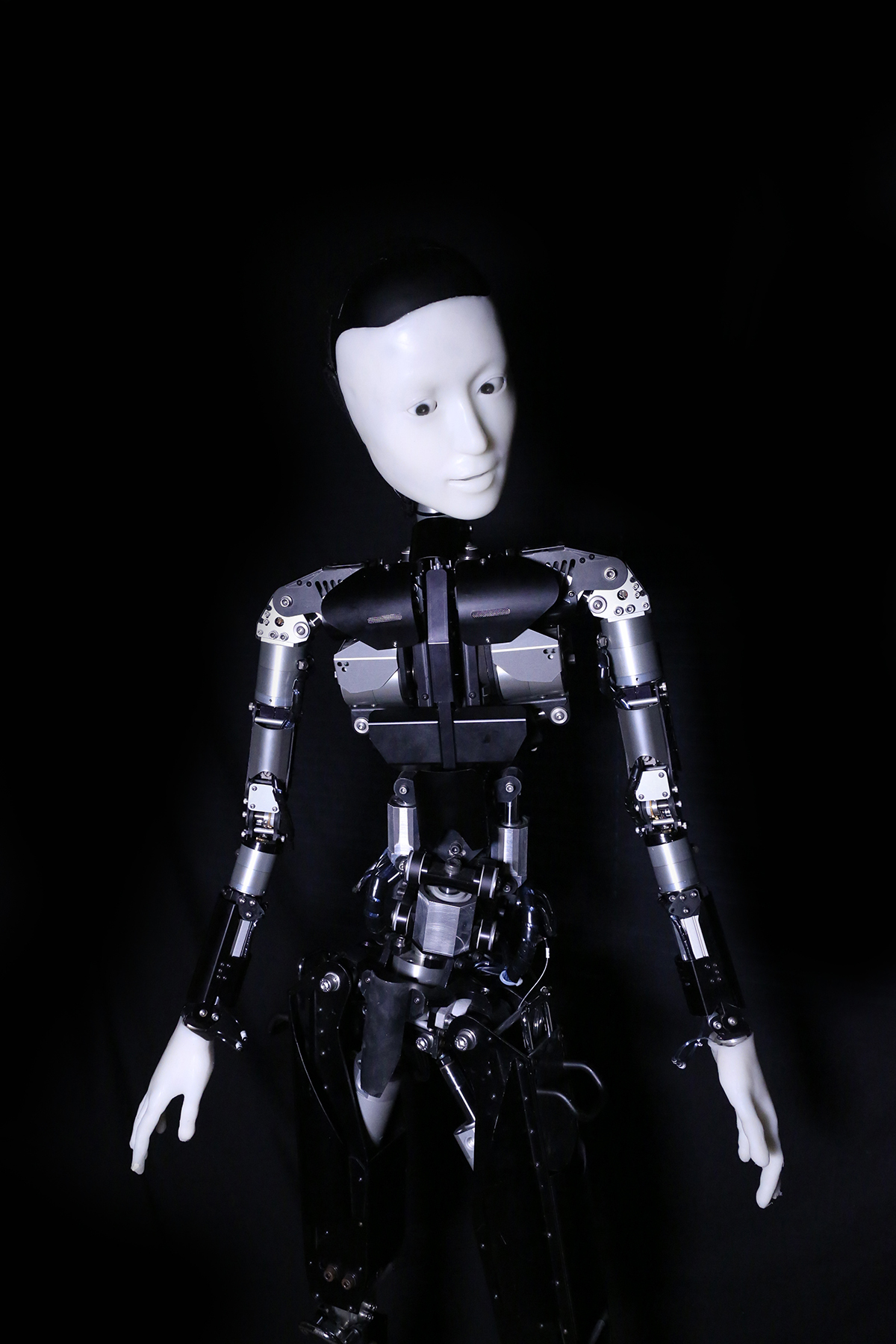

Skeleton, Ishiguro Lab, Osaka University, photo Justine Emard, courtesy OsAsia 2017

Australian Art Orchestra: Keiichiro Shibuya, Scary Beauty

Shibuya makes another appearance in OzAsia 2017 with Scary Beauty, again with a non-human performer — Skeleton, a singing robot with its own neural network — and, again, imagined as a large-scale work. But, says Mitchell, that would have taken years to develop, so the artist was commissioned to present a version of the work with the incisively adventurous Australian Art Orchestra, led by Peter Knight, as part of an afternoon of three discrete concerts featuring Shibuya, guzheng player Mindy Weng Wang and, in Seoul Meets Arnhem Land, Ecstatic Beauty, the pairing of Korean ‘street opera’ singer Bae Il Dong and Daniel Wilfred from the Wagilak clan in the Northern Territory.

Joseph Mitchell sees a widespread preoccupation with robots as workers and service providers as ignoring the rise of AI, which demands of us a better sense of what it is to be human; that, he thinks, can come through art and the challenges offered by works like Skeleton. This cluster of concerts should be a festival highlight, invoking living heritage and evoking possible futures.

Hotel, W!ld Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

W!LD RICE, Hotel

The personal is given an epic dimension in W!LD RICE’s Hotel, 100 years of Singapore’s history performed over five hours. Mitchell describes himself as a slow decision-maker, but within minutes of seeing Hotel he knew he had to program it: “We have to do this, no matter what. It’s one of the best theatre works I’ve seen in the last few years and has never had a bad review. You can see it all at once or in parts and is a bit like watching a Netflix series — there are 11 stories of some 20 minutes each, with characters and incidents overlapping, characters ageing across 40 to 50 years and told through the lives of ordinary people — from British colonialism to the Japanese occupation, independence and the explosion of today’s queer culture.” The hotel is unnamed, but it’s easy to guess it’s Raffles and all that it has symbolised. Mitchell feels that, like Australia’s widely played Secret River, Hotel is a story that needs to be told. Read more about Hotel, Mitchell’s first large scale work for OzAsia, here.

Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn

Although enamoured of earlier works by Kuro Tanino and determined to program him in OzAsia, the auteur’s most recent work, The Dark Inn, proved to be Mitchell’s ideal choice. “The early work was really ‘out there.’ Kuro’s a trained psychiatrist who has worked with a lot of people who don’t see the world the way we do, so he created theatre from their viewpoint. The sets were crazy, with strange dimensions: there were penises across the stage. I saw The Dark Inn in Kyoto last year and agree with people who think this is Kuro’s masterpiece. It won the Kishida Prize for Drama.

“A dwarf father and his tall son are travelling puppeteers booked to play in a country bathhouse but arrive to find a disparate bunch of characters who are not expecting them. In the kind of revolving, multi-level set Kuro’s famous for, with a Japanese bath, steam, inquisitive characters and odd conversations, the play is more about inner states of mind than a straight narrative.” Mitchell adds, “After appearing in major US and European festivals, this is Kuro’s first visit to Australia and is a great opportunity for audiences and those attending the Australian Theatre Forum during OzAsia to see new directions offered by this kind of work.”

Darlane Litaay, Tian Rotteveel, Specific Places Need Specific Dances, photo courtesy Indonesian Dance Festival & OzAsia 2017

Specific Places Need Specific Dances

The collaborative dance work Specific Places Need Specific Dances foregrounds personal desire. Darlane Litaay from Papua New Guinea and Tian Rotteveel from Germany, investigate “waiting in different places, sharing culture and exchanging daily habits” (program). Each visits the other’s home country out of curiosity, says Mitchell, “Darlane to experience Berlin’s underground club and dance scene, Tian to see traditional male garb and in particular the penis horn. To Western eyes, these can appear sexual and as empowering the male figure. There are readings you can take from this work about exchange, sexuality, queer culture and male identity. For me, this is a work which sits at the cutting edge of contemporary dance.” Two more artists, in their Adelaide premieres, confirm Mitchell’s commitment to dance that draws on tradition and local cultures while venturing in new directions.

Aakash Odedra Company, Rising

Aakash Odedra will perform a self-choreographed contemporary Kathak piece and works made for him by Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Maggi Philips wrote of the performance at the 2015 Perth Festival, “Odedra’s presence and collaboration with an impressive list of contemporary choreographers delivered a sense of celebration awakened in a performance which gathered strength from tradition and experimentation alike, yet was humble and projected humankind as simply strange and remarkable in a world of mystery, beauty and pain.”

Eisa Jocson, Macho Dancer

Eisa Jocson, who has appeared in Performance Space’s Liveworks in Sydney and Melbourne’s Asia TOPA, performs her eerie, gender-bending solo work Macho Dancer, drawn from her personal observations of Filipino club dancers. She said in an interview in RealTime, “Macho dancing is performed by young men for both male and female clients. It is an economically motivated language of seduction that employs notions of masculinity as body capital. The language is a display of the glorified and objectified male body as well as a performance of vulnerability and sensitivity.”

I wrote of this striking performance in 2015, “Jocson becomes a young, gum-chewing male dancer passing though a series of telling phases in which he is variously proud, defiant, calculatingly erotic and sulky; at one point he stops dancing and withdraws into upstage shadow — a tease or a moment of existential doubt?”

We’ll tell you more about Joseph Mitchell’s third OzAsia Festival in coming weeks, but already I feel a sense of eager anticipation building around the prospect of entering the idiosyncratic worlds of Akram Khan, Keiichiro Shibuya, Kuro Tonini, W!LD RICE and Darlane Litaay and Tian Rotteveel, with their offers of opportunities to redefine art and self.

–

OzAsia Festival, 2017, Adelaide, 21 Sept-8 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino courtesy OzAsia 2017

Natalie Abbott’s (re)PURPOSE: the MVMNT stages a whimsical and somewhat desultory encounter with The Dying Swan, Mikhail Fokine’s classical ballet solo from 1905. Not that this is in any sense an illustration or adaptation. Abbott is less interested in the work itself than in contesting the discourse that defines the work’s classic status.

Entering the upstairs studio at Dancehouse, we are greeted by the sound of Camille Saint-Saëns’ Le cygne, performed by Miles Brown on a theremin. Once everyone is settled, Natalie Abbott and Cheryl Cameron, both naked, appear from behind the audience and creep slowly across the stage. These may well be dying swans, of a sort: one relatively young and one relatively old. They shuffle forward, both slightly hunched, moving stiffly, keeping close to one another. Their arms waft in a parody of balletic grace.

Natalie Abbott, (re)PURPOSE:the MVMNT, photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Completing their entrance, Abbott and Cameron lie face down on a sheet of silvery foil spread on one side of the stage area. The lights change to sepulchral blue and Geoffrey Watson enters through a door at the back of the stage, clomps over to the prone dancers and upends a bag of potting mix. The swans are laid to rest.

But (re)PURPOSE is less about the performance of death itself than the tragic obsession, perverse in a deep cultural sense, with the performance of death by young female dancers. Cameron and Abbott dust themselves off and read a scripted dialogue in which Abbott asks Cameron to kill her in the next scene. Cameron is not keen on this and the two argue. Cameron shouts. She knows what’s going on. She knows what’s happening. And so do we: wicked Madge or some other older woman must liquidate the heroine. This is ballet’s fairytale logic.

Like much recent independent dance in Melbourne, (re)PURPOSE is a loosely organised and thoroughly decentred work that staggers from one suggestive but half-realised performance idea to the next, revelling in dramaturgical disunity and the guilelessness of its own awkward and misconstrued but unmistakably generous invitation.

Natalie Abbott, (re)PURPOSE:the MVMNT, photo Gregory Lorenzutti

It is cheerful, but a bit complacent. We are presented with two bodies, but there is nothing immediately striking in the contrast, or in the way the two bodies are orchestrated. There is little of the rigour we saw in MAXIMUM, a work by Abbott from 2014 which examined the different physicality of a female dancer and a male bodybuilder.

It is not Fokine’s Swan that is being danced here, but we do at last catch sight of the familiar ballet, emerging briefly from behind the pile of bright ideas. Abbott climbs into a long white tutu and a pair of pointe shoes and performs a few stuttering bourrées. The lights go down and Watson takes control of a small spotlight and begins haranguing her through a bullhorn.

Yes, there are a lot of props, and a lot of different kinds of performance material, including a transcript of a phone interview with Marilyn Jones, a former principal artist and then Artistic Director of Australian Ballet. But to what end? This is choreography which aspires to the condition of critical apparatus, and yet it struggles to convey the necessary intimate knowledge of history and aesthetics and culture.

–

(re)PURPOSE: the MVMNT, choreographer, performer Natalie Abbott, performers Cheryl Cameron, Crystal Yixuan Xu, Rachael Wisby, Geoffrey Watson, dramaturg Frances Barrett, sound design Miles Brown, Alex Cuffe, lighting design Jonathan Wedgwood; Dancehouse, Melbourne, 5-9 July

Top image credit: Natalie Abbott, Cheryl Cameron, (re)PURPOSE: the MVMNT, photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Good Little Soldier, a work by Australian performance-maker Mark Howett first presented in Berlin and newly staged in Perth by Ochre Contemporary Dance Company and The Farm, deals with post-traumatic stress disorder in soldier veterans. After an opening scene set in an outback kitchen, we are briefly thrown back to Frank’s wartime experience in which he and his comrades capture a woman and a boy. Frank releases the boy to assist his colleague in pinning the woman to the floor. A bomb explodes and only Frank survives. The way in which his own family (wife Trish and son Josh) can be read as his enemies returned to haunt him is thus made clear.

Otherwise the work offers few allusions to either wartime experience itself or to how Frank recalls it. It is rather an exploration of the physical and emotional abuse that he inflicts on his family as a result of his trauma. The focus is therefore quite different from works like Angus Cerini’s Debrief (1999) or the National Theatre of Scotland’s Black Watch (2006), both of which included accounts of battlefield experiences and interviews with veterans about how events were replayed in their memories. One of the most terrifying stories Cerini related was how one man awoke with his hands around his wife’s throat. Good Little Soldier is in this sense an extended dramatisation of such later, domestic events. But what is actually occurring in Frank’s mind, or indeed the others’ minds, is only darkly refracted — rather than explicated — through his abusive behaviour.

Good Little Soldier, Ochre Contemporary Dance Company & The Farm, photo Peter Tea

The strength of the piece lies in the way it segues between domestic situations which could plausibly be occurring in a ‘real’ world, into unambiguously hallucinatory scenes. Frank is silhouetted against the window as his ghostly, white-attired dead comrades climb down the walls and suspend his squirming body in the air (crawling down walls has been a choreographic trademark of The Farm since Lawn, 2004; watch trailer here). In another striking sequence, Frank, spotlit from above in the darkness, pushes violently against Trish, before she is replaced by each of the ghosts, and then Josh, in a circling wrestling competition that cannot be resolved — the characters endlessly swapping places and matching each other. Choreographically, the piece is dominated by awkward, violent grappling and pushing: a messy rolling and bumping of bodies which form clumsy, writhing piles or temporarily balanced, off-centre structures, before tumbling down. As with Lawn and other works from The Farm, dancers hang off each other from unusual points, such as the head and neck. Faces seem more sites to push fingers into, or to wrap palms across, rather than sites of expressivity.

Good Little Soldier is episodic with each semi-pedestrian set of gestures, or slapping and physical configurations, caught in repetitive cycles. This has a nasty, imprisoned feel to it, but the production is otherwise somewhat flat emotionally. Frank finally raises his hand to strike Josh, and at one point he dons Trish’s dress before slamming himself repeatedly against the wall. These two acts of shocking violence against his loved ones, and, by implication, against himself (to hit Trish is also to hit himself), act as markers within the protagonist’s breakdown. But otherwise the transition from opening to conclusion is horizontal and open-ended. Each scenario is established before being repeated with minor variations, ending with an exhausted collapse, or a character’s departure. Dramatic development within scenes is rare, and their arrangement largely discontinuous. Therefore the affective content depends heavily on the superb music of Dale Couper and Matthew de la Hunty, together with Laurie Sinagra’s sound design — as is consistent with The Farm’s overall multimedia aesthetic.

Good Little Soldier, Ochre Contemporary Dance Company & The Farm, photo Peter Tea

Speakers are secreted beneath the seating banks such that leviathanic bass rumbles grind throughout the venue, engulfing audience and performer alike. This sense of the corrugated iron shed which the family inhabits as being something we too are trapped inside, is accentuated by regular entrances and exits through the auditorium, or a moment where a drunken Frank thumps under the seating, asking Trish to let him into the house. Couper and de la Hunty’s immersive score runs from low frequency noise music (signifying the war and moments where Frank slips into trauma), through to pulsing synthesisers recalling 1970s kraut-rock, distorted blues/country-and-western guitar solos, as well as manic junk percussion akin to early Hunters and Collectors (which featured Greg Perano on broken water heaters). The overall effect is like a more than usually theatrical gig from The Birthday Party.

The overall dramaturgy of Good Little Soldier feels at best loose. The expressivity of the work echoes instead the slightly rough aesthetic of the outback-style design, post-punk music and deliberately fumbling choreography. It functions more like a series of related installations. This is arguably the most ‘German’ aspect of the show (referred to by Mark Howett in a RealTime interview), placing it firmly within Hans Thies Lehman’s category of post–dramatic theatre. Good Little Soldier is best seen as a striking collection of thematically related set-pieces, giving the performance an absorbing sense of danger and possibility.

You can watch the Berlin production of Good Little Soldier below:

–

Ochre Contemporary Dance Company & The Farm, Good Little Soldier, concept, direction, lighting Mark Howett, choreography, text, performance Gavin Webber, Grayson Millwood, Ian Wilkes, Raewyn Hill, Otto Kosok, performers, music Dale Couper, Matthew de la Hunty, sound design Laurie Sinagra, dramaturg Phil Thomson, set, costume Bryan Woltjen; Subiaco Arts Centre, Perth, 9-30 July

Top image credit: Good Little Soldier, Ochre Contemporary Dance Company & The Farm, photo Peter Tea

“If you have the ability to create the visual language in which you’re speaking from the ground up, who can say no to that?” asks Denah Johnston, curator of Always Something There to Remind Me, a selection of 16mm experimental shorts from Canyon Cinema that recently screened at ACMI in Melbourne and Revelation Film Festival in Perth. Made by women in the US between 1958 and 2015, the technically, stylistically and thematically diverse films point to the breadth of that period’s avant-garde cinema. Out of this diversity arises Johnston’s interest in the nexus between women and representation, and together the films explore agency, social expectations and the gendered gaze.

Canyon Cinema is a collectively-run distribution company that archives independent films. It started in 1961 with informal screenings projected on a sheet hung in the backyard of the archive’s founder, filmmaker Bruce Baillie, in Canyon, California. Jack Sargeant, Program Director of Revelation, feels the new program of Canyon Cinema shorts “show the importance of the archive and of the curatorial voice, but more than this, they reveal the importance of individual filmmakers who pursue their own visions.”

Kristy Matheson, Senior Film Programmer at ACMI, echoes this motivation to bring rarely seen material to Australian screens. “In terms of a local context, I think it’s essential for female storytellers to be able to access a diverse array of works and this program did just that,” she says. “The range of storytelling devices and techniques shows a great range of work that I would hope inspires female storytellers but most importantly opens up the scope for all viewers to the ambitious and free-ranging scope of female voices.”

New cinematic languages

Johnston explains that she curated this program to highlight how women filmmakers have played with the accepted storytelling language of cinema. “There is such a vast freedom in the form. Obviously they’re not all traditional narratives with three-act structures, and I think that taking a film out of those constraints really works well for a lot of the filmmakers. To make experimental work in the first place you’re already making a conscious and aesthetic decision to step out of the narrative.”

The earliest film is Sara Kathryn Arledge’s What is a Man? (1958), started in 1951 but only completed after her release from psychiatric treatment. It’s a collection of bizarre scenes exploring gender roles, starting with Adam and Eve and moving through to modern mannequins. These are humorous, but also affective, with an emphasis on word play, like the nonsense uttered in the “psy-cry-atrist’s” office.

Sharon Couzin’s Roseblood (1974) illustrates cine-dance, centring on the performance of Carolyn Chave Kaplan. Kaplan’s hypnotic movements are interspersed with a surreal, fragmented series of symbols — flower, knife, eyes, hands. Repetition makes these everyday objects strange, and the kaleidoscopic images, dizzying pace and jarring music produce a mysterious and tense film. This is the most lyrical of the shorts, visually enthralling but also decisively and frustratingly abstruse.

Dorothy Wiley’s Miss Jesus Fries on Grill (1973) invokes a different kind of hypnotic meditation, starting with a newspaper detailing the violent death of Miss Jesus, who was thrown onto a grill when a car ploughed into a restaurant. The narrator muses over this horrifying accident as she tends to her baby, bathing, feeding and watching it fall asleep. Her actions are intimate and also palpably everyday, so different from the very unusual and public accident, and the film is immensely disquieting.

Take Off

Women, through women’s gazes

Three of the films interrogate the idea of women as objects, subverting the scopophilic gaze, a psychoanalytic theory popularised by feminist filmmaker and academic Laura Mulvey in 1976. In a defiantly radical political framework, JoAnn Elam’s Lie Back and Enjoy It (1982) aggressively questions the ways women are represented on screen by men, via a dialogue between a female and a male filmmaker. The dialectic takes priority over image here, which is mostly a flickering close-up of a woman’s face from a black and white pornographic film, distorted through looping, reversing, speed and exposure. In Removed (1999), Naomi Uman also edits a porn film, using nail polish and bleach to erase the female body. The fantasy becomes uncomfortably empty and decisively unerotic. Uman’s film comments on female performativity, in porn and in society, reflecting how identity is manufactured through societal conventions. This is echoed in Gunvor Nelson’s Take Off (1972), which also subverts the male gaze and conventional representations of women. She documents Ellion Ness, a famous burlesque performer, as she stages a striptease, which is conventional until she finishes undressing. When the act should be over, she continues the process in what becomes a surreal disassembling of her body. Ness reduces herself to her parts, as revealed to her expectant audience, but is gleefully in control as she discards the layers.

Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (by Kelly Gabron) (1992), directed by Cauleen Smith, also explores the fabrication of identity, specifically through the lens of her experience as a black woman. An example of Afrofuturism, the film layers time, space and history in following the imagined life of Smith’s alter-ego Kelly Gabron. There is a dual-narration from Gabron and a male voice discussing her in the third person, and the entire story is repeated, prompting a consideration of the instability and unreliability of history.

Removed

Collaborative context

Many of the works were collaboratively made and led to further collective activities. Kate McCabe founded the art collective Kidnap Yourself in the town of Joshua Tree, where she discovered inspiration and a creative community. The apocalyptically themed You and I Remain (2015), by McCabe and the collective, is part of the ACMI program. The filmmaker has remarked elsewhere that “you will find more females here behind the camera directing than in the commercial film world and that’s one of the many reasons that field [of experimental film] is vibrant and lush with ideas. The filmmakers I love from the 60s and 70s were breaking new ground.”

JoAnn Elam was also a founding member of Filmgroup (now Chicago Filmmakers) in 1973, which still holds weekly screenings of experimental work. Also in Chicago, Couzin cofounded the Experimental Film Coalition, of which she was president from 1983 to 1988. Some artists collaborated with friends, notably Nelson and Wiley, who made their award-winning first film Schmeerguntz together in 1965, with Nelson revealing that “Dorothy and I needed each other to dare to do it!”

The works are all shaped by socio-cultural discourse and social and professional opportunities offered by second wave feminism, and Johnston draws a comparison between the political consciousness of women filmmakers in the 1970s and today, saying, “right now, I feel like it’s on.”

You and I Remain

Local parallels

Tracing these films, there emerge parallels in Australian cinema history, where there was a surge of women filmmakers in the 1970s. Significantly, there was structural support for this, including the Women’s Film Fund (1975-1990), the Experimental Film Fund (1970-1978) and the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative (1970-1986). There were also collectives like the Sydney Women’s Film Group (1971) and the splinter group Feminist Film Workers (1978) and events like the International Women’s Film Festival (1975).

If much of this government funding has ceased, or at least changed significantly, there continues to be critical — and importantly, public — interest in women filmmakers, with film festivals now providing the backbone of structural support. There are dedicated festivals like For Film’s Sake and Stranger With My Face Festival, which provides mentorship for women developing genre features, while OtherFilm has held several exhibitions and festivals of avant-garde work in Brisbane and at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. Jack Sargeant notes, “this isn’t to say that there shouldn’t be more spaces, more funding or whatever, but there are people making and exhibiting works, so, while the situation could always be improved, I don’t see it as entirely bleak either.”

–

Always Something There to Remind Me, Canyon Cinema retrospective, curator, Denah Johnston, presented by ACMI and Revelation Film Festival, ACMI, Melbourne, 5 July; Perth, 9-18 July

Kate Robertson is a cultural critic with a PhD in Art History & Film Studies, and has written about arts and culture for The Atlantic, Vice, Marie Claire, i-D, Junkee, Overland, 4:3 and Senses of Cinema.

Top image credit: Chronicles of a Lying Spirit

We all play roles in our work and home lives and often are assigned these in childhood by our family. We are the ‘bossy one,’ ‘the baby,’ or ‘the black sheep.’ These roles trail us into adulthood and they become our default setting when we are faced with big events — cataclysmic grief, heady love and loss. The roles we are all cast to play both conceal and reveal us.

Enter the self-proclaimed ‘comical woman,’ a part both played and railed against in He Dreamed a Train and Eve, the double bill from inimitable Brisbane theatre maker Margi Brown Ash.

He Dreamed a Train, Margi Brown Ash, photo Stephen Henry Photography

He Dreamed a Train

He Dreamed a Train, directed by Benjamin Knapton, is a paean to a loved brother and an intimate encounter with one family’s experience of loss. The work is inspired by real events — the degenerative neurological disease that prematurely claimed the life of Margi Brown Ash’s brother. We are warmly invited to bear witness to her grief, and share in it too.

The show opens when the bereft narrator, Margi, returns to the family home, to pack up her brother’s belongings and excavate old memories, perhaps in order to make some sense of the tragedy to herself. There are still things she has to say to him.

The brother presents as a dreamer type. He is visionary at times — his idea to revitalise regional communities by linking them with a monorail holds a kind of wacky genius appeal. Yet he infuriates in his refusal to accept treatment or find ways to stymie the onset of his symptoms.

Margi tells us what she cannot say to him: that if it were she who was sick, she would try everything — yoga, Pilates, acupuncture, the works — to stave off illness. This treads the line of the tragicomical, sort of like drinking a green juice to combat cancer; it might help, but it does not address the larger issue. When those you love are dying, there are conversations that are just too difficult to have. Instead we try to fix things through action, in this case with helpful suggestions for alternative therapies.

He Dreamed a Train, Travis Ash, Margi Brown Ash, photo Stephen Henry Photography

The set is comforting; it could be any one of our lounge rooms and we are lulled by its familiarity. Except of course for a lone picture on the wall. A seemingly innocuous sky scene, one might find in an old opp shop, becomes a beautiful digital image, evoking Brown Ash’s emotional landscape. Just as what remains unsaid builds in momentum, the painting is a living artwork throughout: the clouds rain, the heavens open, the sky bleeds down the wall.

Time jumps into the childhood home where the characters are visited by their younger selves, entertaining each other with mythological tales, dragon legends and their own creation stories. The most potent of these are train moments — the children playing chicken in a train tunnel, a family legend which becomes significant later in the work.

But the grieving sister cannot stay silent in the end and refuses to be diverted by these ghosts. At one point Brown Ash demands to speak not with the 25-year-old version of her brother, charmingly rendered by performer and musician Travis Ash, but “the sick old man” who has let them all down by dying too young. Her anger in this moment is palpable and affecting. The ‘comical woman’ has been cast aside. This is the kind of role that floats away like vapour when there is no one left to play with.

Yet all families have creation myths, stories we tell and retell. In them, no one dies, not really. The lost loved one is always there, just behind the clouds in the picture on the wall.

Eve, Margi Brown Ash, Travis Ash, photo Stephen Henry Photography

Eve

Eve, which was first staged in 2012 and is directed by co-devisor Leah Mercer, sees another figure struggling with the roles she is expected to embody. This show is a gloriously exuberant ‘biopic’ of the life of Australian novelist and poet Eve Langley (1904-1974), billed in the program as Australia’s answer to Virginia Woolf. This time, Brown Ash as Eve ricochets between the roles of ‘brilliant writer’ and ‘wife and mother,’ delivering moments of humour and pathos in equal measure.

We first see Eve banging away furiously on her typewriter in an iron tub in a bathroom open to the elements: a kind of a lean-to off her bush hut. She appears to be hiding out from the prosaic demands of her husband and small children, snatching precious moments with the muses where she can.

Margi Brown Ash draws on the artist’s published and unpublished writings to offer us a glimpse into the cosmos that is Langley’s interior world. In this makeshift room of her own, Eve dips deftly in and out of bush poetry, religion, astronomy and mythology. Her mind is nimble, and her ability to weave together these tangents to create vivid and startling imagery, gives us an insight into its dazzling velocity. Brown Ash’s performance of these excerpts matches the verve and wit of Langley’s writing.

As Eve works in the bath, manuscripts tied with string drop with a thud from the ceiling. We are lovingly introduced to these works as if they are her children. However, some of these parcels contain rejection slips. We also learn Langley was a furious correspondent, hilariously advising booksellers that she is happy to accept returned manuscripts only if addressed to Oscar Wilde, since he could ostensibly handle them better than she. Her acerbic sense of humour is highlighted; the ‘comic woman’ is a role Langley evidently both played and downplayed. She wears a topee hat, men’s strides and appears to cultivate a wild bush raconteur’s demeanour. Humour is her way of handling what cuts her to the quick, yet Eve longs to be recognised as more than amusing.

Eve, Margi Brown Ash, photo Stephen Henry Photography

Perhaps it is the rejections that prompt Eve to return to her domestic role and its responsibilities for a time. After a spate of creativity, we see her cross the threshold into her home proper. In this role she is less successful, although she does try. Eve’s mind shrinks, not soars. The detailing of the set, designed by Aaron Barton, is incredible, evoking the sort of household objects and collectibles found in a Margaret Olley painting. But all this is a distraction for Eve, just more stuff crowding her already busy brain. Domestic miscellany is too much in the end, or perhaps not enough. The artist cannot deny her true self and write she must, drink in hand all through the night and even as the sun rises, family be damned. In this retelling, Eve solves her childcare problem by upending her babies on the mantelpiece. By standing them on their heads, she reasons, they cannot fall — genius in its madness. Her husband has her committed to a mental hospital, nonetheless.

After her release, Eve continues to write, though she will struggle with the duality of these roles for the rest of her life. Ironically it is her adult children who, upon their mother’s death, discover a cache of Langley’s writing secreted away under her bed, as Emily Dickinson had done. It is they who marvel at her words, her true essence, concealed for so long and they who vindicate past neglect.

As a woman writing at a time where the roles of ‘wife and mother’ and ‘artist’ were often seen as mutually exclusive, Eve explores the theatre of playing house while needing to create and inhabit other imaginative worlds. The tragedy of Eve Langley’s life was not that she was denying her true self — the artist was fully aware that she needed her writing to ground herself. She had two great loves, her family and her work, but it was demanded that one be chosen at the expense of the other.

Eve and He Dreamed a Train are linked thematically by their bush settings, their artful tapestry of mythology and personal story and by Margi Brown Ash’s disarming impulse to stop for a cup of tea mid-show. We too are invited to pause and consider the roles we play, to look through and break out of them. That is the great, generous gift of Margi Brown Ash in works, crafted with skill and love.

–

Force of Circumstance, Nest Ensemble & Brisbane Powerhouse: He Dreamed a Train, writer, performer Margi Brown Ash, director, set & AV designer Benjamin Knapton, performer, sound designer Travis Ash, A/V content Nathan Sibthorpe, lighting designer Geoff Squires; Eve, writer, co-deviser Margi Brown Ash, director, co-deviser Leah Mercer, co-deviser Daniel Evans, performers Margi Brown Ash, Travis Ash, design Aaron Barton, costume designer Bev Jensen, sound designer Travis Ash, lighting designer Geoff Squires; Brisbane Powerhouse, 2-16 July

Victoria Carless is a writer living in Brisbane. Her first novel, The Dream Walker, was published by Hachette Australia in July.

Top image credit: Margi Brown Ash, Travis Ash, Eve, photo Stephen Henry Photography

Garry Stewart’s visceral and intellectually provocative Be Your Self plays in Melbourne 2-5 August prior to a wide-ranging ADT tour. Watch this 2012 realtime tv interview with excerpts from the performance.

Sadly, Tony Woods, a highly inventive Australian visual artist whose films and light-filled paintings we have long admired, died unexpectedly in June. In 2013 we published a review of Tony Woods: Archive in which writer Danni Zuvela described the work of this important Australian artist:

“Invited to muse on the aesthetic and conceptual relations between the artist’s practice across canvas, celluloid, pixels and audio tape, we start to develop insights into how the dialectic of representation and abstraction powers an artist like Tony Woods, finding varied expression across forms, materials and decades.”

Tony Woods: Archive is a wonderful record of the life and work of this much-loved Australian contemporary artist. It’s published by www.artinfo.com.au and distributed by Australian Scholarly Publishing (ASP).

The book includes a richly informative 55-minute DVD of the documentary Tony Woods: Work for the eyes to do, which you can see below. Or you can watch a 20-minute summary of Woods’ life and art currently posted as a tribute to the artist on his website.

Virginia & Keith

–

Top image credit: 1994 same chair changed light situation, oil on canvas, Tony Woods: Archive, image courtesy the artist

Thai-Australian playwright Disapol Savetsila’s Australian Graffiti has its moments: flashes of crisp, acerbic dialogue, grim physical comedy, occasional deft character delineation, vivid arguments and some emotionally sensitive exchanges. It’s otherwise underdone — character development is limited, critical motivation unexamined and the tonal shifts in language and mood between the scenes with and without a ghost character are minimal in the play’s easy-going naturalism, despite a press release claim for its “magical realism.” For real magic you need to turn to Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, winner of the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, in which ghosts can slip in and out of the world with unnerving effect.

Faults aside, Australian Graffiti warrants attention since Savetsila is another in a number of new culturally diverse voices coming to Australian stages and performance spaces and needs to be heard, not least for the essentially dark vision entailed in his story of Thai-Australian business failure compounded by Australian racism and traditional Thai attitudes to filial duty. For all of its leavening comic moments, the play offers at its end only a sliver of hope for cross-cultural conciliation.

Mason Phoumirath, Airlie Dodds, Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Amiable chef Loong (Srisacd Sacdpraseuth) has died — his body heartlessly lugged about by the play’s other characters in bouts of black comedy — but visits as a ghost, encouraging those who listen that there is life beyond a failing Thai restaurant in a regional Australian town. The elegantly dictatorial Baa (Gabrielle Chan) continues to run the business with a ruthless work ethic, regardless of the absence of customers. Illegal immigrants — boisterous, despairing Boi (Kenneth Moraleda) and the more hopeful but ill Nam (Monica Sayers) — have become Loong’s replacements, but are not good cooks (they desperately experiment with Vegemite dumplings). Moving the business from town to town has forced home education and separation from his peers on Baa’s lonely, intelligent adolescent son and waiter Ben (Mason Phoumirath). However, a chance meeting by a creek introduces Ben to Gabby (Airlie Dodds), a caustic, tough-minded white Australian of his own age who introduces him to yabbying. This is where the play opens with youthful banter and marked sexual attraction, although Gabby drolly mocks the idea of a relationship tainted “with the stigma of sweatshop labour.”

There’s a bitter edge to joking in Australian Graffiti. Gabby’s father (Peter Kowitz), a nasty character of the bullying Australian “can’t you take a joke” variety grows angry when humour is directed at him: “You speak good English,” he says to Ben, who retorts, “So do you.”

Ben and Gabby’s meeting at the play’s end will be a test whether or not Ben can continue the relationship with the only friend he has ever made (if barely so) and if Gabby can separate herself from the racism of her policeman father and the townspeople. After their first meeting, she’s been resolutely hostile, feeling — because of Thai graffiti appearing on a church altar wall — that Ben and family have turned her private paradise into a hell. It’s not much of a town, but it’s hers, she declares with passionate conviction in one of the play’s stronger moments. But there’s little to indicate in the course of the play that she’s capable of the insights that come at its end. Ben, more convincingly, is determined to develop the friendship and break free from the restaurant and his mother’s insistence on gratitude for her sacrifices (“I’m building an empire for you!”). A girl and a ghost draw him out of a smothering cocoon which he knows has never been ‘home,’ although the options for him to remain in the town seem profoundly limited as his mother moves on.

Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

The executor of the graffiti is finally revealed and the symbols translated, but the meaning is enigmatic and the motivation behind it left infuriatingly unexplained — an opportunity lost to deepen both a character and the possibility for shared understanding between cultures in conflict. Why might someone be driven to commit such an act? It also prompts the question, why Australian Grafitti? Is it ironic? The graffiti in the play is Thai, it spoils and desecrates, but the disproportionate response (Ben accused, the violence, banishment in effect) and unleashed racism could be seen as graffiti writ large on the immigrant body.

One of the strongest images in the play is of a small girl who is sighted recurrently peering into the restaurant until, with her black eyes, she becomes a frightening apparition for the nervy Boi, racism incarnate. A crowd forms, rocks are hurled, windows broken and we learn later Gabby was one of the perpetrators. Other moments linger: Loong’s enticing Ben to relish the freedom inherent in eating fresh mango and his wise discourse on entrapment with the metaphor of dogs happily fattened up to be eaten: “suicide by food,” he quips. His admission, “All I have is hindsight,” is one the play’s best from Srisacd Sacdpraseuth’s engagingly realised ghost character, who grumpily complains to Nam that when he was dying, her over-vigorous CPR broke a rib. His funeral, after days of lying about and ritually held in the restaurant building for fear of alerting authorities to the presence of illegal immigrants, becomes an aptly incendiary affair for a sower of doubt.

Monica Sayers, Srisacd Sacdpraseuth, Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Australian Graffiti’s limitations were underlined by a large, high-walled greyish, fluoro-lit set (representing a room adjoining the unseen restaurant) that, although amplifying Ben’s sense of homelessness, reduced the sense of intimacy and entrapment felt in the writing and produced, at times, over-projection from some of the performers (a late reference to the room as a former ballet studio didn’t compensate).

Despite its occasional strengths and strong performances, Australian Graffiti’s appearance on an STC stage was clearly premature. It’s not without promise, but Disapol Savetsila deserves dramaturgy that will address the gaps in the work and opportunities to follow through on the complexities he conjures.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Australian Graffiti, writer Disapol Savetsila, director Paige Rattray, performers Gabrielle Chan, Airlie Dodds, Peter Kowitz, Kenneth Moraleda, Mason Phoumirath, Srisacd Sacdpraseuth, Monica Sayers, designer David Fleischer, lighting designer Sian James-Holland, composer Max Lyandvert, sound designer Michael Toisuta; Wharf 2, Sydney, 7 July-12 Aug

Top image credit: Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Upon The Babadook’s release in 2014, Katerina Sakkas wrote in RealTime that “the most powerful horror films are underscored by reality, presenting recognisable fears and anxieties in magnified and fantastic form.” Indeed, writer-director Jennifer Kent’s debut is a haunted-house horror film of folkloric dimensions and feminist temperament, in which a family home harbours the unspoken terrors and taboos of parenthood. A small boy’s beloved storybook monster morphs into a far more sinister organism, a long-fingered, top-hatted creature called The Babadook that torments his mother, who is in the throes of grieving her partner’s death.

Three copies courtesy of Umbrella Entertainment.

Email us at giveaways [at] realtimearts.net by 5pm 2 August with your name, postal address and phone number to be in the running.

Include ‘Giveaway’ and the name of the item in the subject line.

Giveaways are open to RealTime subscribers only. By entering this giveaway you consent to receiving our free weekly E-dition. You can unsubscribe at any time.

On the occasion of our DVD giveaway of The Babadook, already recognised as a canonical Australian horror film, we revisit Katerina Sakkas’ illuminating interview with director Jennifer Kent.

So much of contemporary life feels as if it’s shattering. In the art ecology, the labour market, the housing sector, media business models and politics, things aren’t working like they used to. But sparks of fresh life are coming from surprising places. Ancient sky spirits speak to us in Warwick Thornton’s documentary, fresh from the festival circuit. Perth theatremakers are breaking apart the very atoms of narrative and putting them back together in weird and inventive ways. In a renovated substation in Melbourne, Angelo Badalamenti’s 25-year-old Twin Peaks soundtrack is remade by an art-rock band. And we continue our series of video essays by Conor Bateman — RealTime is the only publication in Australia to consistently commission such audiovisual works, as part of our effort to find new means to bring words and images together in works of creative criticism. The old ways are gone, but glimpses of the new are all around. LCH

–

Top image credit: We Don’t Need A Map

Warwick Thornton entered cinema’s global attention in 2009 when his debut feature film, Samson and Delilah, won the Camera D’or prize at Cannes Film Festival, but his presence has been long felt in the Australian creative community in many capacities — as cinematographer for Rachel Perkins’ Radiance (1998), as a photographer and conceptual artist exhibiting at such spaces as ACMI and Stills Gallery, and now as a documentary-maker. Earlier this year, Thornton’s We Don’t Need A Map was the bold choice for opening night at Sydney Film Festival (whose program dwelled heavily on issues of race) and this month broadcasts on NITV.

The film takes the Southern Cross as its focus. Unbeknown to those who tattoo it on their shoulders and fly it on their flags as a symbol of nationalist pride, the constellation has its own myriad significances for Indigenous Australians, whose knowledge of astronomy is a form of mapping, ritual, storytelling and moral education, that exist as one with stories of country. Thornton takes us away from the city and into a number of Aboriginal nations, to hear elders tell their culture’s story of the great constellation, which turns out to be a crucial wellspring in creation lore. Along the way, we also hear from academics and artists, offering a 360-degree viewpoint on what the Southern Cross means when stripped of its exclusionary and muddle-headed political connotations.

Press materials describe the film as a punk roadtrip doco, with irreverent sequences involving bushranger puppets and dioramas, but it has much broader implications: Australia has a problem relating to the past, as if history has only recently arrived young and free in this most ancient continent, and Thornton proves himself a forensic dissector of the myths, delusions and rhetoric that dominate the history wars from the Eureka Stockade to the Cronulla riots, to today. His vision is a long-sighted one, grounded in ancient protocol and law and faithful to fact and history in a way that both reveals and respects the secrecy of Indigenous, pre-industrial knowledge, while also showcasing the insights and wisdom of some remarkable non-indigenous Australians.

LCH I learned heaps from this documentary. The image of the Southern Cross constellation reflected in the side mirror of a car door seemed to me to be a great visual symbol of the film’s approach. What’s your impression of the film?

TY That reflected image idea is a big part of the knowledge Thornton is working with. In our cultures Skycamp in many ways is a reflection of the earth, with sites, stories and songlines in an “as above so below” kind of arrangement, stemming from the Turnaround event of creation that separated the material and spirit worlds into earth and sky. They reflect each other, overlapping at sacred sites and through the kind of ritual practice that is depicted in the film. An image of a person or entity is sacred because it holds the spirit of that thing — so the word for spirit and image is often the same in our languages. This is the reason we often avoid images and names of the deceased. It is the same reason the old men in the film erase the Southern Cross symbol following the ritual.

LCH To me the doco spoke to how symbolism can be twisted and mutated. It made me realise that nationalist usage of the Southern Cross in contemporary Australia is the most grotesque form of cultural appropriation. What are your thoughts on this?

TY As the old men said, that image is sacred and cannot be kept; it certainly cannot be marked on the body outside of ceremony. The people who adopted the Southern Cross image for flags and tattoos as a symbol of nationalism based on exclusion and privilege are really cursing themselves and their own people, from this perspective. But it is simplistic to frame this as a “white” thing, or Australian thing, and I think the film explores this in a more nuanced way. I was particularly struck by the switched-on Anglo people who were interviewed — their self-awareness and critical reflection are a credit to them and their community. No denial or defensiveness — their level of awareness and perception in critiquing their own culture is a great strength and does not diminish them — it makes them complete people. They are comfortable with discomfort and committed to truth as a way of life. They set a good example for others to follow. Duane Hamacher, for example, who is interviewed at a stone calendar site at the beginning of the film, has done exciting work in this field.

We Don’t Need A Map

LCH It is fascinating to learn more about Indigenous astronomy, which has an understanding of the negative spaces between stars. Thornton describes it as not just being about navigation, but interviews someone who says, “the night sky, for us, was the whole of philosophy.” As one of the elders says, “all these stars are connected to all these trees,” and all the stars are related, too, rather than being carved into discrete, lonely constellations.

TY The idea of astronomy as a mere navigation tool is very industrial and utilitarian, and our star knowledge goes way beyond that. All the memories are up there in the stars — the night sky is a vast mnemonic device that is used to store terabytes of knowledge. These memory maps are used to navigate mind and memory over deep time, to hold ancestral knowledge so vast that it would be impossible to contain in print. This knowledge is also held in songlines all across the land, and in inner maps held in the mind, so they can be accessed without actually being in the place or even looking at the sky. This is our literature in oral cultures, and it was the same for everybody in the world until very recently in human history. You can see it in the early works of Western literature, like Homer’s epics, which were oral texts initially before being written down. This orientation to knowledge and memory results in a way of knowing that some people call “pattern thinking,” which modern science is now exploring through complexity theory and fractals; it allows us to see the whole as well as the parts and discern patterns in what some see as chaos, to make accurate predictions about weather systems and human behaviour. Some of us are even currently applying this Indigenous reasoning to economic trend analysis (and let me tell you, the outlook for the near future doesn’t look good!).

LCH The film talks about how the Southern Cross connects land and sky stories. Is there any information embedded in the film that an audience member without deep Indigenous knowledge would miss?

TY That information is present, but difficult to see through a Western lens, particularly a perspective based on binary oppositions — male/female, light/dark, land/water, heaven/earth. It is all about the connectedness and transformative overlap between things that some see as opposite, the vast songlines that connect freshwater to saltwater, Skycamp to earth, men to women. The inland stories are connected to coastal stories, and these are stories of transformation and transition. There is also lots of latent information embedded in the film about women’s business and men’s business. With the canoe ritual in the film we see the common overlap between the two — when the old lady is singing we glimpse the power of women’s knowledge and the old matriarchal authority, the edge of it where it overlaps in a common space that can be accessed by all the community. The rest is so secret and so powerful — you’ll notice the women do not share with Thornton beyond this. The power and agency of women in our culture is seldom acknowledged in the mainstream — the Western lens frames us as patriarchal and abusive when it comes to gender relations. That’s the binary thinking again.

LCH I don’t think that mainstream Australia really understands that Indigenous custodianship and care extends from the land through the air to the sky — that’s the extent of colonialism’s theft, too. Do you think We Don’t Need a Map conveys the expanse of Indigenous ecology and thinking, this sense of a galactic robbery?

TY This is not just Indigenous knowledge, but human knowledge that all people had until recently. Industrialised and colonial thought is imposed and kept in place through a kind of cultural brainwashing, disconnecting people from what they really are. It is not as simple as black and white — it is about industrial and non-industrial reasoning. Scratch the surface and you’ll find that all around the world people all call the Seven Sisters constellation the same thing, with a similar story. Orion is always a hunter or warrior. Castor and Pollux are always two brothers. Aquila is always an eagle. All people globally are connected to these songlines in the earth and sky, and have only recently had their knowledge and communities fragmented. Most people in the world are dispossessed from not only their ancestral lands, but also their ancestral thought. All this disconnection and diaspora serves the interests of only a few people in this temporary experiment of industrial civilisation. The good news is, it is only a blip in the vast human story, and will not last. Who knows, maybe your grandkids and mine will one day be sitting under the stars and seeing the same story together again.

LCH At one point, one of the elders greets the black night by saying, “Hey, night.” That’s a pretty unusual thing to hear in film: the treatment or characterisation of an environmental concept as a person or a being. I think that kind of sentience has mostly been seen in science fiction films: I’m thinking of the Russian classic Solaris, followed by Steven Soderbergh’s remake, in which the ocean has a consciousness.

We Don’t Need A Map

TY Science fiction has a solid tradition of exploring the sentience of complex, self-organising systems. In literature, China Mieville probably does it best, although his books have not been made into films yet. It only occurs in fiction because the Western academic requirement of objectivity is a barrier to understanding our true relationship with the sentient universe. This academic view is placeless and seeks a mechanistic and broadly generalisable explanation of all phenomena, while the observer must pretend she or he does not exist while reporting it. The place where the observer stands, the standpoint within a dynamic landscape, must also be invisible. Indigenous knowledge is seen as subjective by the Western academy, but from our viewpoint the cosmos is communicating with us, so the things we see from our personal perspective grounded in our location are part of the story. So in the film you see that old lady singing the star story and including everything that happens in that moment in the song — clouds passing across the sky, birds flying, fish jumping…this is all part of that story of Skycamp and its communication with us in the moment.

LCH There are parts of the film that betrayed its television production origins: I found that the emotional tone and generic registers were not well sustained, and the digressions into rap, punk road trips and bush puppet reenactments were distracting. I think it would have been stronger and more sustained if it was a pure essay film, as the PR material described it. But I really loved the connection between talking heads in the bush, and Professor Ghassan Hage, who talks about how the Southern Cross is embedded in wider discourses of racism and fear that “have made refugees into exterminable objects” and of a “culture of exterminability” whereby we refer to inanimate, sinkable “boats” instead of people.

TY That discourse of exterminability is made possible by the false objectivity I mentioned previously, rendering the observer/speaker unaccountable and as invisible as the victims of their discourse. This is why the academy has historically de-emphasised subjective, supra-rational, diverse and place-based ways of thinking. I think the film does well in privileging these kinds of seemingly irrational and disjointed worldviews. It draws on a punk aesthetic to reflect this in the domain of contemporary film, and as you mentioned earlier it is an act of culture jamming. I don’t see this work as inconsistent; the film is characterised by constant and deliberate code-switching, not just between dialects and social registers but between genres as well. At times this is jarring but it is supposed to be. Warwick Thornton achieves this code-switching effect masterfully, and with a genius and humility that makes him my new favourite filmmaker. And he is never the invisible observer — we often see him in shot while he himself is filming another angle. This visibility makes him accountable for the knowledge he portrays and speaks to his cultural integrity.

LCH Yes — the way that Thornton casts himself as the filmmaker and central character, guiding us through the film, as well as the self-reflexive shots of him beside his cameraperson, is really important in showing that he’s a fallible human. He’s absolutely not playing the role of documentary’s traditional and supposedly objective, onscreen authority figure, like Michael Moore. How did you think the old stories told by elders related to the Western film techniques of talking heads and time-lapse photography? Do you think there’s such a thing as an Indigenous cinematic language?

TY Diversity is one of the few things that Indigenous cultures and languages have in common. As such, there isn’t really a single Indigenous anything, let alone a common cinematic language. Thornton incorporated the same kind of talking heads you see in docos like SBS’s series First Australians, but with the old people out bush in cultural contexts he did something quite new. He brought the viewer into the yarn, sitting alongside the knowledge keepers, and he wove the protocols of Indigenous knowledge transmission into these intimate episodes — something that is glaringly absent in the talking heads sequences filmed in the city. It forces the viewer constantly in and out of a sense of connectedness, so that we experience a sense of loss and separation over and over, instilling a cultural desire for authentic connection that endures long after the film is over.

LCH Another interviewee in the film, Dr Romaine Moreton, says, “I don’t think identity is contained in symbolism.” To me the film spoke to the limits and power of symbolism in personal, community and national identity. What did you think of her take on the relationship between identity and symbolism?

TY The transient cultures of industrial civilisation must constantly be shifting the meanings of symbols and memes to suit the shifting goals of ‘progress,’ which are dictated not by cultural needs but by the requirements of continual economic growth and resource extraction. Identity, meaning, movements and metaphors emerging organically from the demotic in human cultures are constantly co-opted and absorbed, then twisted to suit the needs of the powerful. Note for example the shift in the last 30 years in the meaning of symbols and metaphors pertaining to the idea of freedom. Freedom no longer means escape from tyranny, but the right of business interests to act without accountability for damage done to systems, land and communities. In Indigenous cultures, the symbols and stories that make up our identities endure in our Law, retaining their integrity of meaning over deep time. Our wealth is knowledge, not money and resources. Power for us is about accepting accountability for protecting sacred knowledge. Warwick Thornton honours his accountability to the knowledge that is shared with him in this film, and demands that his audience does the same.

–

We Don’t Need A Map, 2017, director, writer, cameraperson Warwick Thornton, writer, producer, cameraperson Brendan Fletcher, interviewees Adam Briggs, Dr Romaine Moreton, Prof Ghassan Hage, Baluka Maymuru, Bruce Pascoe, executive producer Marcus Bolton, in English, Warlpiri, Wardaman, Dhuwala and Dhuawaya, broadcaster NITV, 23 July

Top image credit: We Don’t Need a Map

With the end nigh, is it more important to take action to save the world or to create happiness for those around us?

Where theatre company Ten Tonne Sparrow’s first show, The Epic, was about creation myths, their new show forms a counter-response. The premise of Tamagotchi Reset and Other Doomsdays isn’t whether a catastrophe is imminent — that’s taken as a given — but the ethical ramifications about what to do while the world burns. Writers-cum-characters Scott Sandwich (sound artist and theatre-maker Tom Hogan’s stage name) and playwright Finn O’Branagáin take us on a tour-de-force through the doomsday myths of previous generations, from the fall of the Mayan empire to the nuclear bomb fears of the Cold War era. Eschewing a conventional narrative arc for an extended storytelling debate, Scott and Finn present their thoughts in a series of abruptly contrasting, thought-provoking and entertaining vignettes.

Introducing themselves as Scott and Finn respectively, Izzy McDonald and Paul Grabovac argue each position in a stream of energetic lectures, bringing a personal dimension to leaven the strongly researched and fact-rich material. It’s an inherently self-reflexive and self-referential production: the actors refer to director Joe Lui, introduce their own characters and establish an engaging ‘odd couple’ rapport that binds the production, with the gender swap emphasising the viewpoint and approach rather than the individual. Scott celebrates the achievements of humanity and the ongoing potential for creating happiness, while Finn succumbs to existential melancholy. They namecheck all manner of Judgement Days in a grab-bag mix: IBM engineers visiting a Tibetan mountaintop to assist a group of Lamas to hasten the end of the universe, the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef, and the death of teenaged Finn’s counterfeit Tamagotchi rat as Y2K hits during New Year’s Eve parties in Darwin. The unprepossessing yet demanding digital pet was hatched, fed, cleaned and played with, and Finn had reached a new month-long record of survival for this incarnation, when the keychain-sized electronic toy found itself unable to cope with the calendar demands of 2000. The recently relaunched Tamagotchi device is far more sophisticated, and Scott’s kind gift to Finn of the new and improved model informs designer Sara Chirichilli’s animated backdrop to the presentations, the cute pixel display responding to each apocalyptic scenario.

Paul Grabovac and Izzy McDonald, photo courtesy of EClaire Photography

Tales escalate at a slick pace as Scott and Finn broach the limits of their power as individuals to arrest environmental and societal collapse. McDonald shares Scott’s wonder at NASA’s Golden Record Voyager and its lonely arc through space; Grabovac rants Finn’s despair at the cycle of worry created though the ethical implications of every choice we make. Their mutual frustration with the other’s perspective grows. A detour to ancient Egypt brings a flurry of terror as benevolent Hathor turns into raging Sekhmet; we learn that what we love can destroy us and redemption is available in the form of beer as Finn and Scott follow the ancient rite to placate the enraged god of the Nile. Paul presents Finn’s deeply mournful elegy to the Bramble Cay melomys, a cute but isolated rodent from a small island on the Great Barrier Reef, using a fishbowl, ice, blowtorch and stuffed toy to evocatively demonstrate the first recorded mammalian extinction from anthropogenic climate change, contrasting with Scott’s playfulness in a roaring tribute to dinosaur existence.

Chirichilli’s brightly coloured, geometrically-styled set features versatile storage solutions from which illustrative props spring. Finn reflects on the escalating cycle of deforestation, competitive head carving and eventual starvation and slavery that led to the Polynesian island of Rapa Nui’s ecological and social collapse, whimsically expressing it all with a tray of Easter confectionery. Scott declaims the mythos of Cthulu, replete with old-timey dramatic foreboding. Scott’s beanies figure prominently and are emblematic of the playful costume design, incorporating Cthulu, alien Carl Sagan and triceratops among other elements of the apocalyptic case studies.

Tamagotchi Reset and Other Doomsdays evokes late 90s nostalgia, entertains through the didactic content and the contrasting of Finn’s earnest activism and Scott’s light-hearted compassion, using humour to offset the sudden and strident bursts of information. Scott and Finn declare their production a modern day version of an Easter Island monumental stone head, and despite the impending doom, we’re brought to a surprisingly upbeat ending that acknowledges the problems in this time and place, inspiring us to pursue our own hearts in the meantime.

–

The Blue Room Theatre & Ten Tonne Sparrow, Tamagotchi Reset and Other Doomsdays, director, dramaturg, lighting designer Joe Lui, writer, producer Finn O’Branagáin, writer Scott Sandwich, performers Izzy McDonald, Paul Grabovac, assistant director Michelle Aitken, designer Sara Chirichilli, sound designer, composer Tom Hogan, stage manager Sean Guastavino, The Blue Room Theatre, Perth, 20 June-8 July

Top image credit: Izzy McDonald plays Scott Sandwich in Tamagotchi Reset and Other Doomsdays, photo courtesy of EClaire Photography

Though it’s known for its mysterious imagery and disquieting phenomena — chevron stripes, inexplicable crying, clairvoyant logs, lessons of adolescence, slowly swishing leaves, red curtains and extra-dimensional rooms — Twin Peaks is a remorselessly sonic television series. Angelo Badalamenti’s compositions are the hooks the show hangs on and any attempt at merely covering these songs would be rather exasperating. Fortunately, Californian ‘art-rock’ band Xiu Xiu has no such desire. Their reinterpretation of the music of Twin Peaks is more like a meeting of two personalities; a metamorphosis where Xiu Xiu and the work of Badalamenti and Twin Peaks co-creator, David Lynch, relentlessly feed into each other.

Last year Xiu Xiu reinterpreted Badalamenti’s compositions with its album, Xiu Xiu Plays the Music of Twin Peaks, released as part of the David Lynch exhibition, Between Two Worlds, at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art. Created in the 1990s, Twin Peaks remains a pivotal piece of Lynch’s oeuvre: an arthouse series that introduced us to both auteurist television and the murder of a small-town, blonde-haired and blue-eyed, homecoming queen. The show works by transforming a seemingly simple detective story — who killed Laura Palmer? — into scenarios that take on difficulties not often well addressed in popular television: domestic violence, abuse, incest, evil spirits and demonic possession. Likewise, Badalamenti evokes the melodrama of soap opera scores and the rhythms of jazz, only to summon something far more obtuse and perverse, the latency of which is intensified by Xiu Xiu’s reinterpretation. Xiu Xiu recently toured the album to Brisbane and Sydney, with two shows at The Substation in Melbourne, the second of which was supported by Canadian musician Sarah Davachi performing her own original work.

Xiu Xiu performs the songs of Twin Peaks, courtesy of The Substation

Sitting alone on stage, surrounded by her minimal equipment, Davachi has a purposefully understated presence. Primarily working with electronic music, Davachi’s performance builds on repetition, overtones and density. Her sustained and droning sounds both compete and interweave, so that no singular sound is allowed to stray from the pack. The darker layers protrude, while the more melodic lines lie buried: prominent enough to be heard, yet doing the trick of withholding melodic catharsis. Instead, Davachi’s music delivers a different joy; the peacefulness of the layered flat line.

Between Davachi’s and Xiu Xiu’s performances, I hear a few people comment upon the “positively Lynchian” qualities of The Substation as a venue. With its working class history, semi-industrial aesthetic and thick red curtains, it contains that conflation of mood and setting that is so pivotal to the Lynchian oeuvre. Xiu Xiu references the Lynchian penchant for dramatics by beginning the performance not with music but an essential and recurring visual from Twin Peaks on the stage’s screen. The camera incites us to look up the Palmer household staircase, briefly focusing on a moving ceiling fan, before resting on Laura Palmer’s open bedroom door. It’s an enigmatic moment that holds both Laura’s absence and presence, mixing banal domesticity with wordless terror. As this scene changes to a spinning fan and the Douglas Fir trees of Twin Peaks (visuals that repeat throughout the show), we’re continuously reminded not only of Laura, but the absence and presence of Lynch and Badalamenti.

While this initial scene holds our attention, Xiu Xiu’s Angela Seo walks on stage and hits ‘play’ on a drum machine. After setting off a repetitious single-hit pulse, she walks off, leaving the beat on loop. It’s a rather cool move and a few minutes later the entire band emerges. Seo sits behind her piano and plays Laura Palmer’s Theme, which contains those two incredibly authoritative opening chords, before further escalating the song’s quasi-soap opera moment, adding dissonant layers to heighten the already-grandiose climax. Shayna Dunkelman takes to the vibraphone (and it’s a pleasure just to watch her nimble grace), while Jamie Stewart initially sets himself behind a drum kit, his snare hits and cymbals eliciting a feeling of stress for the audience, a certain affectation that Stewart builds throughout the show. This dual preoccupation with homage and light theatrics persists throughout the night. While this could be viewed as overly self-conscious, to my mind it speaks to the generosity and emotional investment of the group’s performance.