Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

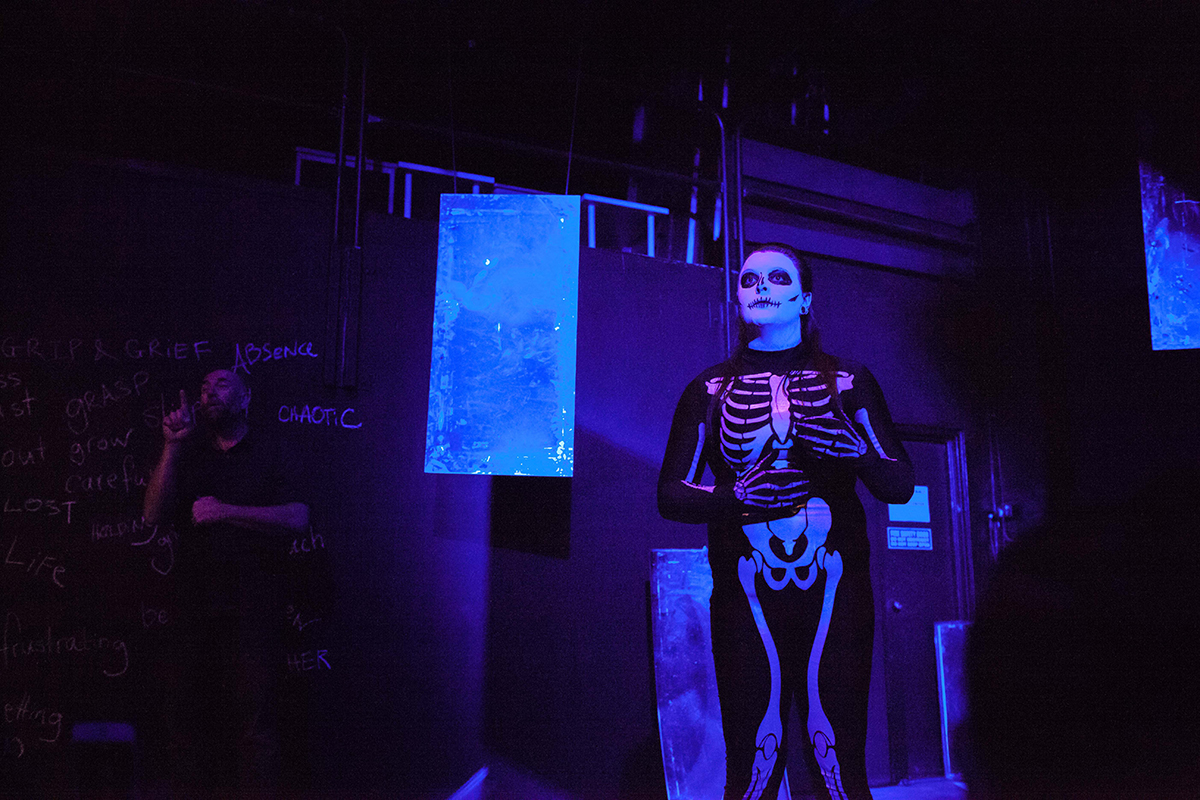

In this edition, we have more about Adelaide’s forthcoming OzAsia Festival, introducing you to idiosyncratic Hong Kong visual artist Doris Wong Wai Yin (installation image above). In our ongoing Arts Education feature, Nat Randall anticipates her 24-hour performance of The Second Woman for Performance Space’s Liveworks and looks back to her formative years at the University of Wollongong.

Democracy is being eroded on all sides: Australian copyright is under threat from the Productivity Commission, media ownership looks set to fall into fewer hands, the same-sex marriage postal vote creates an appalling precedent for non-compulsory voting and Immigration Minister Peter Dutton’s assault on pro bono lawyers defending refugees is unconstitutional. This at the very moment he is maltreating those for whom all Australians have a duty of care. Call the Government out. Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: A Place Never Been Seen is Not a Place, Doris Wong, photo Kwan Sheung Chi, courtesy OzAsia 2017

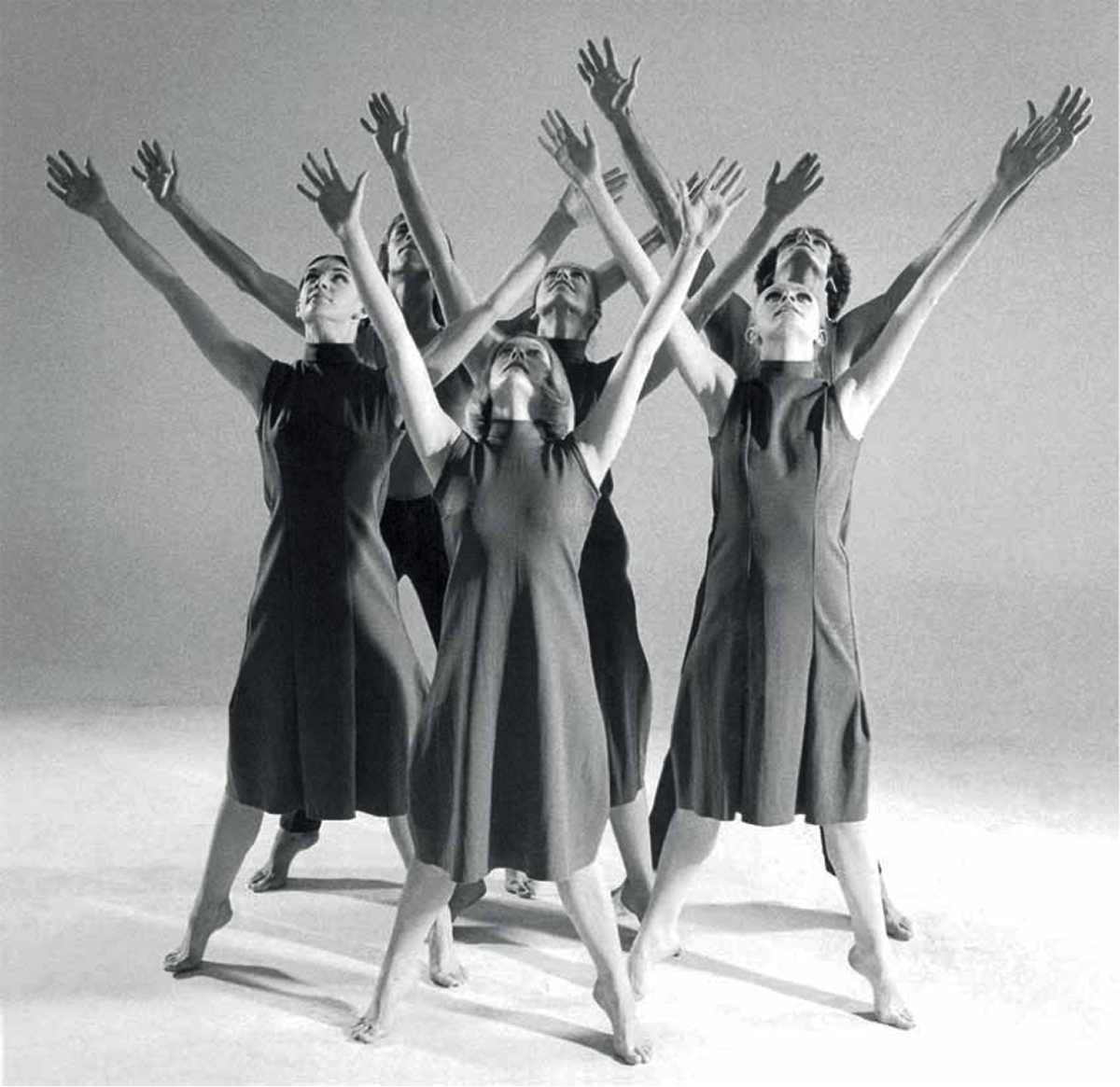

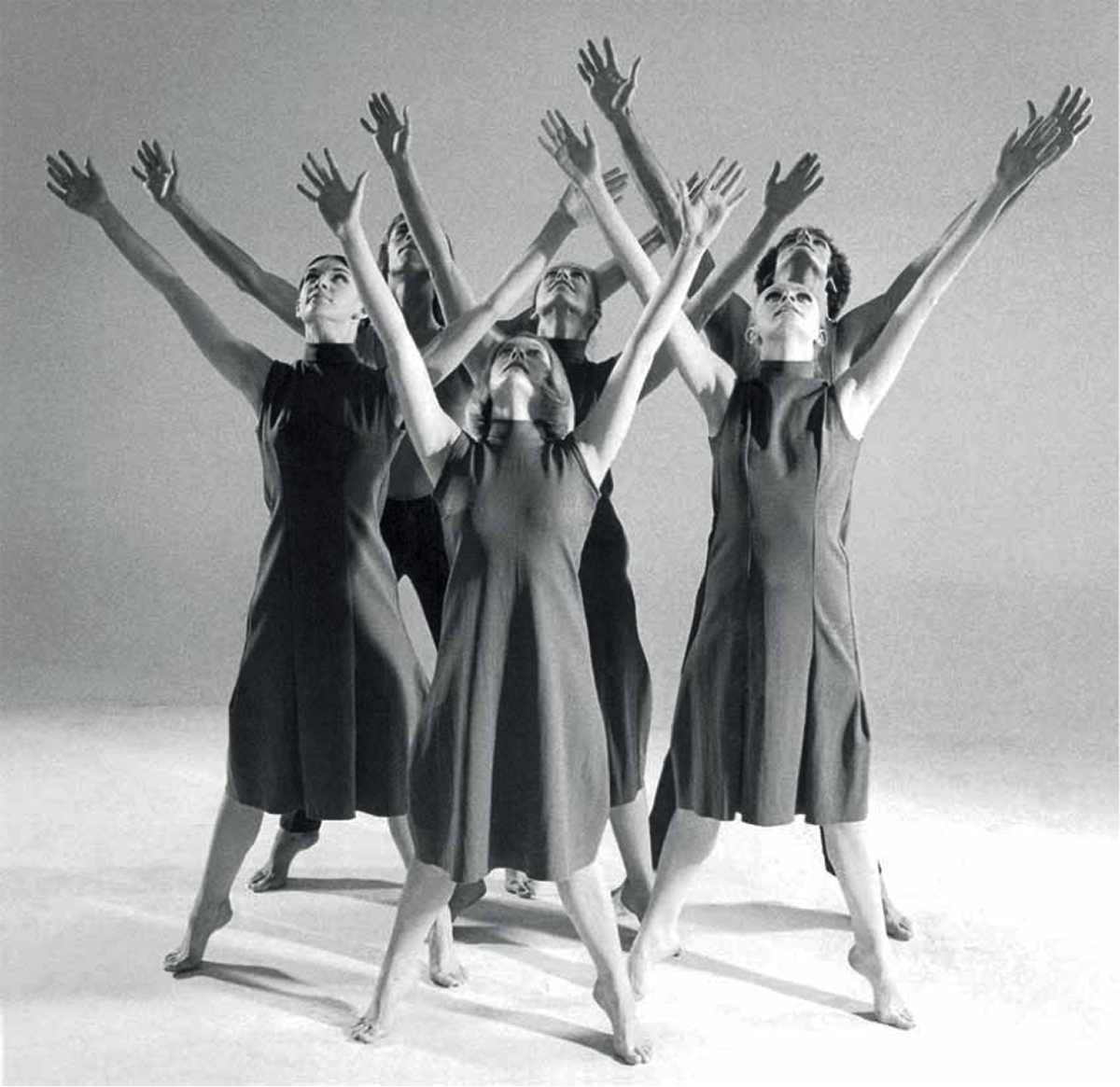

Though human history is far too chaotic to move in predictable cycles, there’s a poetry to the notion that dance history has something of that rhythmic flow to it. In Melbourne, at least, the period of 1995 to 2005 saw a flurry of activity as new companies formed — the likes of Chunky Move, Lucy Guerin Inc and Phillip Adams BalletLab — whose influence is still obvious today. Then came a time when dance activity was no less energetic, but the stable of companies mostly remained the same. Who would fill the generational gap? A pair of recent works at Arts House delivered an encouraging reply.

Both Stephanie Lake’s Pile of Bones and Melanie Lane’s Nightdance are clearly made by choreographers young enough to have spent more than a few nights at clubs, dance parties and outdoor festivals. The ecstatic, spontaneous rituals of these experiences are baked into the choreography, and this is one of the notable features that seems to be cropping up in work by dancemakers their age and younger. It’s a generous act, looking to harness the energy of a shared dancefloor, and a world away from the cerebral spikiness of purely form-based dance.

Jack Ziesing, Samantha Hines, Marlo Benjamin, Pile of Bones, Stephanie Lake Company, photo Bryony Jackson

Stephanie Lake, Pile of Bones

Lake’s choreography in particular has long been inflected with emotional expressiveness detached from narrative. Pile of Bones furthers this by producing a set of evolving relationships that a viewer can supply their own meaning to, whether through imagination or experience. A powerful opening sees its four dancers as one organism, emerging into narrow light like something ejected from primordial darkness. As the forms split, their physical complexity multiplies too, though they’re still a long way from the human — think a Francis Bacon painting without the ick factor.

Whether animal, vegetable or even molecule, these figures develop in an evolutionary rush, and soon enough the universe has expanded to the point that they can become small, more still, under the majesty of the night sky in the Australian bush — though, again, this is one viewer projecting onto the sound and movement that composer Robin Fox and Lake have built. The next person along might read something entirely different into the stage pictures this work strives towards. They might not read anything, which is always the danger of choreography that seems so pregnant with meaning but never gets literal about it. However, there’s no doubting Lake’s ability to produce both robust and thoughtful dance.

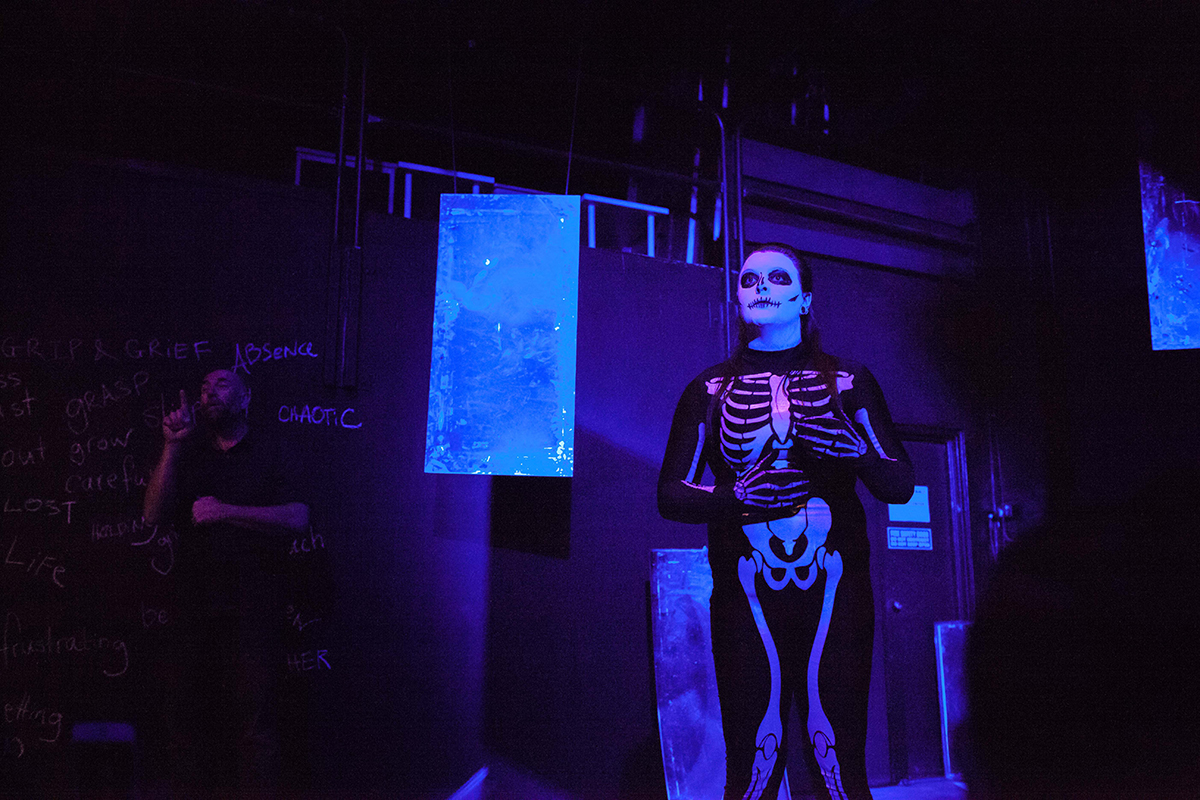

Melanie Lane, Lillian Steiner, Gregory Lorenzutti, Night Dance, Melanie Lane, photo Bryony Jackson

Melanie Lane, Nightdance

Melanie Lane’s Nightdance is even more fearless in its personal vision. There was a moment late in the piece when I was forced to put my note-taking aside and just accept that I had no frame of reference for what I was seeing. You’ll know it if you were there. It’s a work that shouldn’t be spoiled, but that doesn’t prevent discussion — there are no twists, as such, but it’s an hour of frequent surprises.

An extended, hypnotic opening sequence sees three dancers undulating in an ochre haze, the animal eroticism to their movements balanced by the technical precision with which they’re performed. The trio almost never uncouple their gaze from the audience, lending a presentational aspect that’s part sex show and part mating display, and the libidinally-charged set-piece establishes the tone for what will follow.

Nightdance isn’t about sex, exactly, but its evocation of nocturnal life — from the bed to the dancefloor — necessarily yokes sexuality to its performance. To a driving beat a succession of memorable figures emerges on stage, transforming the space as they do so: now a drag club, now a fetish den, now a rave. There’s a polymorphous perversity to it, not merely in the free-floating desire that hovers over everything but in the instability of the visual image itself. At one point a figure is so bedecked with sequins that they almost appear to be composed of digital pixels, while another sequence features a dancer I didn’t even realise was there for a long time.

I’m still trying to make more sense of the finished work, but this is Lane’s triumph — Nightdance is filled with secret dramas and impenetrable mysteries the way that any dancefloor is, and it’s stitched together with the tight but invisible logic of a dream. And like a dream, when you’re in it you don’t question why this carefully but inexplicably costumed character appears at one point, because there’s an emotional sense to it that’s beyond waking thought. That Melanie Lane successfully puts her audience in that state is a rare triumph, and one that won’t be forgotten.

–

Pile of Bones, choreographer, director Stephanie Lake, performers Marlo Benjamin, Samantha Hines, Harrison Ritchie-Jones, Jack Ziesing, composer Robin Fox, lighting design Matthew Adey, costume design Harriet Oxley; Arts House, 15-19 Aug; Nightdance, choreographer, director Melanie Lane, co-creators, performers Lilian Steiner, Gregory Lorenzutti, Melanie Lane, sound design, composer Chris Clark, lighting design Ben ‘Bosco’ Shaw, costume design Ryan Ritchie, Benjamin Hancock, Sidney Saayman; Arts House, North Melbourne, 24-27 Aug

Top image credit: Melanie Lane, Sidney Saayman, Lillian Steiner, Night Dance, Melanie Lane, photo Bryony Jackson

Doris Wong Wai Yin makes art to explore the nature of art and her own nature and presence in the world. Her first exhibition in Australia, at Nexus Gallery in the 2017 OzAsia Festival, will offer just a glimpse of the very substantial body of work she has produced since she graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2004 and completed her Master of Fine Art at the University of Leeds in 2005.

Wong uses painting, sculpture, collage, installations, photography and performance — whatever suits her purpose — and has exhibited in Taiwan, Japan, the USA, Singapore, the Netherlands and Guangzhou as well as Hong Kong. Strongly conceptual, her work up to 2012 was characterised by an exploration of what constitutes art, while the work I decide to make 100 Paintings to learn and unlearn PAINTING 1-111 (2014) specifically addressed the one artform. Many of her works have been made in collaboration with her partner Kwan Sheung Chi, for example, videos in which both perform, such as Everything Goes Wrong for the Poor Couple (2010), with its stuttering black and white 16mm film-style footage, part of a 34-hour, five-day performance and installation.

To Defend the Core Values is the Core of the Core Values (2012), Doris Wong Wai Yin, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

There is often humour and wit in her work, but as is clear from her essay on her six-month residency at the Asia Art Archive in 2011, she is concerned with the wider role of art in society. During that residency, she created a new archive of Hong Kong art, drawing on alternative sources of information such as failed applications for residencies which she includes to identify the potential value of unrealised artistic work. She thus questions the accepted history of Hong Kong art and challenges more generally the traditional sources of art history. And so the issue of Hong Kong’s identity emerges from the investigation of its art history.

Another strategy is for Wong to invite audience participation. For example, in To defend the core values is the core of the core values (2012), made with her partner, participants could win a solid gold coin embossed with the phrase “Hong Kong’s Core Values” by expressing what those might be. The work comments on Hong Kong’s commercial profile internationally and its people’s pre-occupation with material wealth, at the same time asking fundamental questions of a post-colonial society that is in political and social transition.

Man’s Future Fund, Doris Wong Wai Yin, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

Wong temporarily stopped making art about five years ago, explaining, “Just after my marriage… I was so confused about the duties, whether I should cook the meals or something.” Shortly thereafter, the birth of her son also had a significant impact. The baby was small and she and her husband were frightened that their son, who they named Kwan Man, might not survive, but he did (the couple created for him a distinctive long-term project, Man’s Future Fund yielding new works for sale each year). “This was the first day of my life I believed the power of belief… It was a very intense lesson, the first time we really experienced what life and death is.”

Wong’s art changed as a result and there is now a much more personal, even spiritual, aspect to it. For her Wish You Were Eternal (2016), she cut up paintings she made from 2005 to 2016 and placed the fragments in a series of timber pyramids, thus enclosing her own art history in objects that suggest crates but, in evoking Egyptian burial chambers and the transportation of the deceased to the afterlife, invite historical investigation. She had planned this work for two years and engaged a psychic medium to detect messages that might lie within it. The medium identified the Hindu goddess Kali who symbolises destruction and rebirth. It seems that for Doris Wong the transition to motherhood was profound and this work symbolised that transition; it publicly enacted the rebirth of her art and preserved and historicised her previous artistic self.

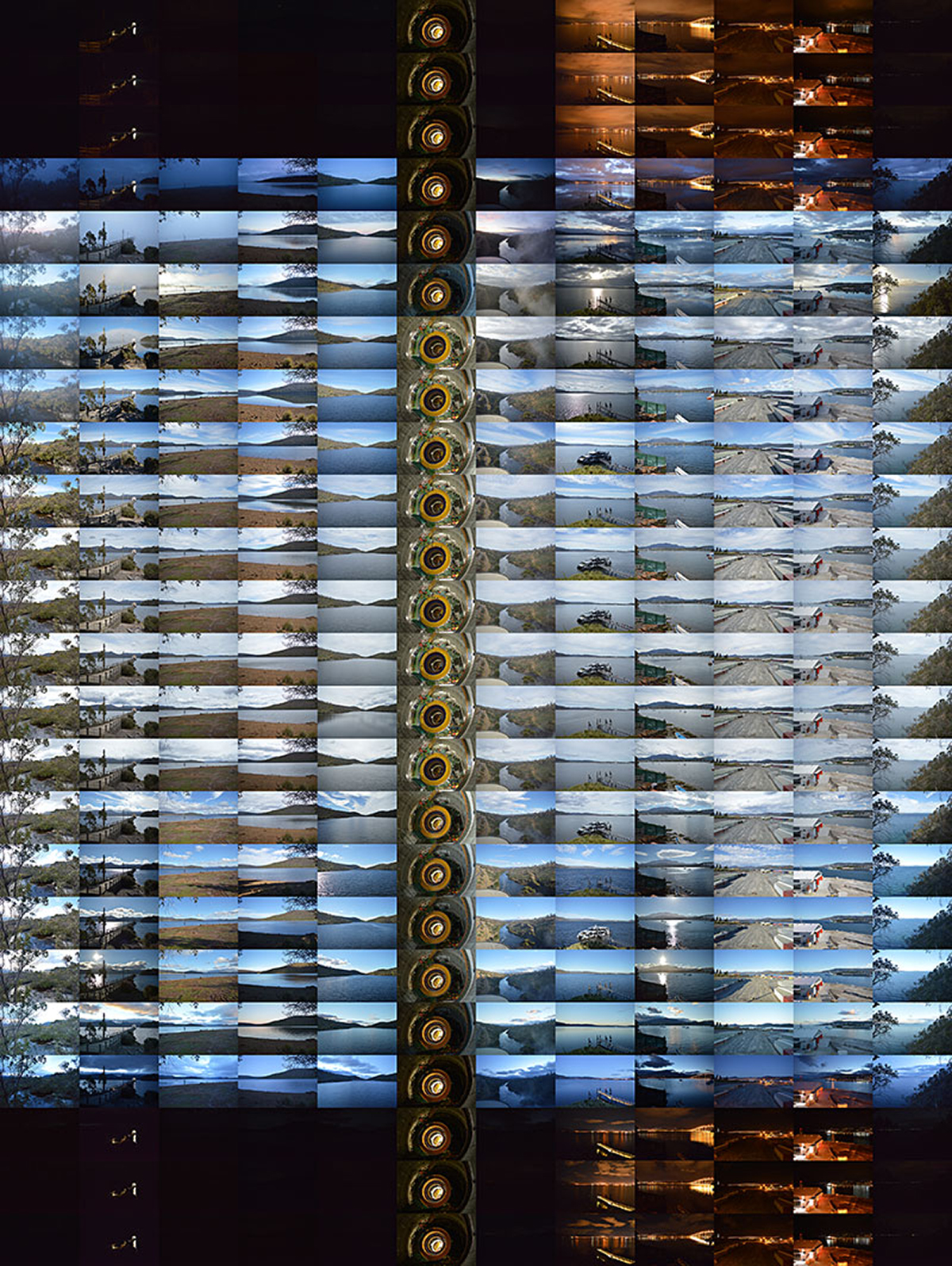

A Place Never Been Seen is Not a Place, Doris Wong, photo Kwan Sheung Chi, courtesy OzAsia 2017

Wong’s work for OzAsia 2017 exemplifies OzAsia Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell’s “focus on very personal and intimate stories told from Asia”. Titled A Place Never Been Seen is Not a Place, Wong’s installation is based around a telephone booth and videos, including an image of the Earth rotating inside an unusual object. The phone will ring, inviting audience members to answer. Spoiler alert: Wong says, “if you answer there will be someone reading a page of a book… the book is called Conversations with God.” The installation “is about how I perceive the relationship between myself and the universe… The first step of your healing is confronting your fears.”

–

OzAsia Festival, Doris Wong Wai Yin, A Place Never Been Seen is Not a Place, Nexus Gallery, Adelaide, 7 Sept–8 Oct

Chris Reid visited Doris Wong in Hong Kong courtesy of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council and the Adelaide Festival Centre.

Top image credit: Doris Wong Wai Yin at her Hong Kong exhibition, A Place Never Been Seen is Not a Place, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

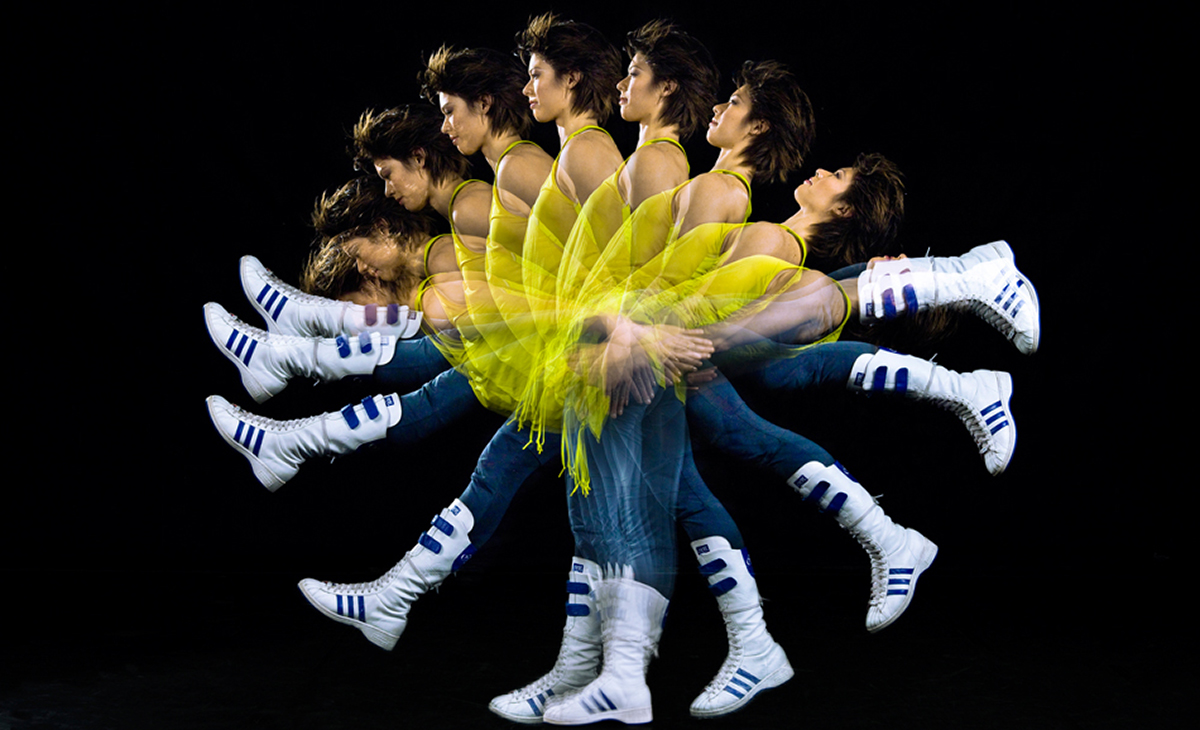

A pink, neon-lit motel room nestles in a foreshortened cube on a stage. A blonde-wigged woman, Virginia, waits patiently. A selected but unrehearsed male member of the public enters the set as Marty, her husband, and plays a scene with her. It’s a domestic, verbal war of minute dramatic shifts and long-simmering resentments: the couple argue, they dance. Virginia demands her partner’s compassion and Marty brickwalls her. The scene lasts around three to six minutes, depending on how the pair interact. Two camera operators capture the action in six shots and a projector beams their live edits onto a screen beside the set. Marty has been given a script beforehand and one crucial moment of agency: to vary his final line of dialogue, choosing between “I love you” and “I never loved you.” Virginia hands him $50 (his fee for performing), he departs, and the loop starts anew with a new audience member.

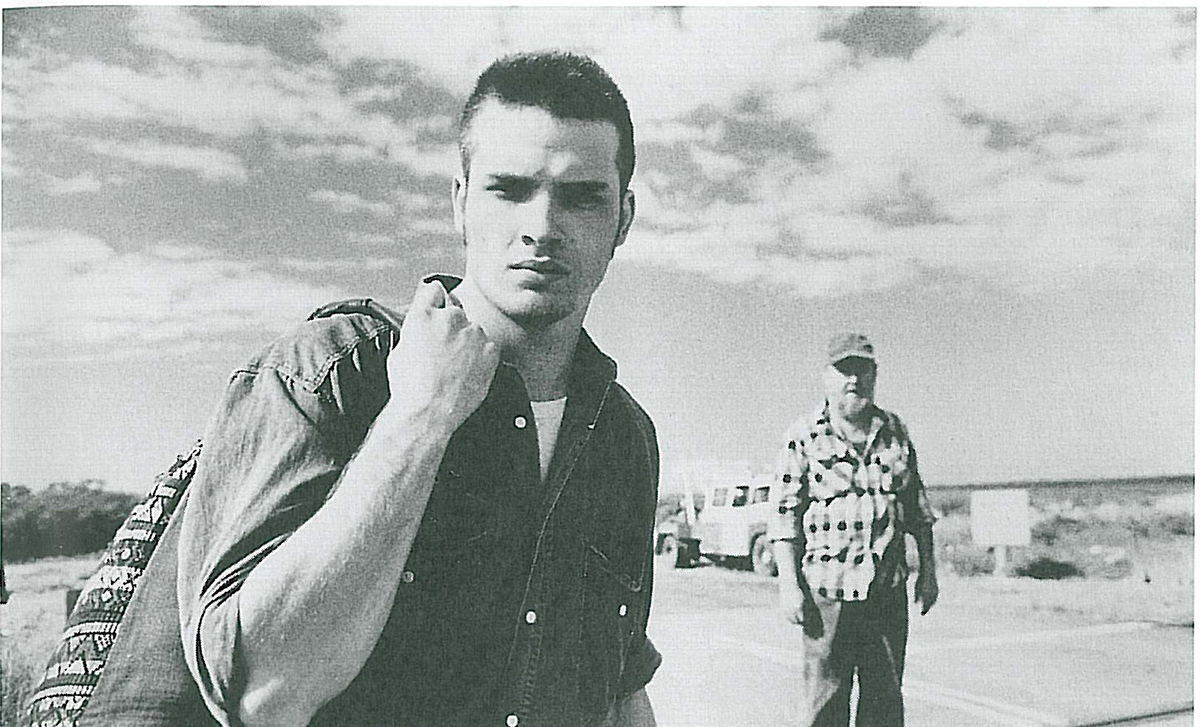

This is The Second Woman, in which Sydney artist Nat Randall invites 100 men to act opposite her in a scene from John Cassavetes’ Opening Night, replayed live over 24 hours. The 1977 drama featured Cassavetes’ real-life partner, Gena Rowlands, as Myrtle, an ageing stage actress cast as Virginia in a play about what she calls “the gradual lessening of my power as a woman as I mature.” Myrtle is worn, alone, drinking heavily but stoic in her devotion to her character and the play, and the film, described by scholar George Kouvaros as a story about “the figure of the female performer in crisis,”, continually violates the boundaries between on-stage, on-screen and real life.

The Second Woman continues Randall’s trajectory of making risk-taking and experimental work since graduating from the University of Wollongong in 2008 and working with live performance groups Hissy Fit and Team MESS. Randall performed The Second Woman at 2016 Next Wave Festival and at Dark MOFO this year (read Briony Kidd’s review). I spoke with her and collaborator, filmmaker and dramaturg Anna Breckon as they prepared for the work’s third outing at Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art in October. “It began with our interest in multiple levels of performance,” says Breckon of the project’s evolution, citing Opening Night’s “trickiness” as a film, and its many reference points to Hollywood backstage dramas and 1950s melodramas like All About Eve.

The Second Woman (video still), Dark Mofo, 2017, image courtesy the artists

Performing intimacy

“Watching Opening Night,” says Randall, “I was attracted to the different layers of performativity and the slippage between three relationships that Gena Rowlands had with Cassavetes,” who was the director of the film, her husband in real life, and plays ex-husband Maurice in the film and ex-husband Marty in the play within the film. “They had these three levels of intimacy and performed that intimacy, and I hadn’t seen anything like it. I was so taken with this inability to locate [just] one emotion from the three levels, and the possibility of [translating it into] live performance. That was the genesis for me.”

Having dealt with the bureaucratic hurdles involved in staging a round-the-clock performance in Sydney — Carriageworks’ venue licence had to be modified to allow 24-hour operation, which was only approved by the council the week of the Liveworks program’s launch — the pair are now free to focus on “opening up” Randall’s performance.

“After doing it twice, it’s difficult to bring freshness. Anna and I are working towards opening me up as a performer to be much more responsive to each participant and whatever energy or intention they bring into the room. I’ve been attempting to be more open, but I return to ‘lockedness.’ You just return to crutches when you’re exhausted.”

Myrtle’s defining struggle in Opening Night is also to stay present against the lock of habit and the slope of indifference. She says, “When I was 17 I could do anything. It was so easy. My emotions were so close to the surface. I’m finding it harder and harder to stay in touch.” Perhaps the relationship between Opening Night and The Second Woman is growing closer as the latter evolves across its iterations.

“I read the dynamic [in the scene] between the two as the end of intimacy,” says Randall, “where Anna reads it as too much intimacy; but whatever it is, it’s the end of an intimate space between a man and a woman.”

One man or many?

The surprising element for Randall has been the blurring of a stream of different men into a single man. The memory of one Marty to the next passes across performances: the many iterations of the male character merge into one and slide from scene to scene interchangeably. What emerges from the format of a repeated script is a passage, made deeper and wider in each restaging, in which a single male character is rewritten along fairly similar lines by a succession of non-actors, who tend to perform learned and stereotypically alpha-male behaviour. It’s that fastened positioning between Randall and her procession of onstage counter-agents that the pair are now working to revitalise as Liveworks approaches.

“The work’s model of repetition allows difference through sameness and sameness through difference,” says Randall. “The generic rises to the fore when you consider a spectrum of men over 24 hours. A sameness and predictability and boredom emerges, but also this quite melancholy space. It’s interesting how many of the men play at the same level, [even though] there’s no character summary or emotional preparation [given to the participants].”

The Second Woman (video still), Dark Mofo, 2017, image courtesy the artists

From the University of Wollongong…

Contemporary art in Australia has taken a distinct postgraduate turn in recent years, with artists increasingly making work within Masters and PhD programs under the banner of creative research. Since her undergraduate days at the University of Wollongong — which has a reputation for producing inventive live art practitioners like Malcolm Whitaker, Dara Gill and the Team MESS, re:group and Applespiel collectives — Randall has forged a divergent path by primarily participating in residencies and festivals. Her practice has been founded on constantly and collaboratively devising work with other artists and curators — and, ultimately, audience members.

“I haven’t established my practice within an institution. What I got from the University of Wollongong was a really robust sense of the history of performance art and theatre through a really incredible dramaturgy course which was compulsory for every one of the performance practitioners. That theoretical framework was so important and fed into the practical parts of the course. We did conventional acting but we also had movement and voice classes. The practical was intrinsically tied to the theoretical. There are not many places that do that. It’s very contemporary. And you are trained to be resourceful for when you get out of the school, to be proactive in creating your own work that challenges the canon.” For Randall, it has meant devising work “to challenge what it means to be a woman and to be queer today.”

While everyday performativity is central to John Cassavetes’ films, a broader iteration of it comes into view in The Second Woman where repetition, duration and video-framing push cinema into a large-scale live art framework. Anna Breckon brings her knowledge of cinema to the partnership, while Nat Randall brings the participatory and durational components. “I don’t know how to make work by myself. It’s always collaborative,” she says, and the audience completes that collaborative circuit.

“There’s been this weird collective journey that we didn’t anticipate,” says Randall. “The audience has been on this journey with us and wants to finish it with us. For the first iteration, I thought, ‘who the hell will turn up at three in the morning’ [to watch performance art]. But people come and they stay. There’s something quite special about that collective viewing at a time when nothing’s happening in the city.”

–

Performance Space, Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, The Second Woman; Carriageworks, Sydney, 6pm, 20 Oct – 6pm 21 Oct

NOTE: Tickets are $15 and available on the door only. Ticketholders receive a wristband allowing them to enter and exit the theatre over the 24 hours until the theatre reaches full capacity.

Top image credit: The Second Woman (video still), Dark Mofo, 2017, image courtesy the artists

Meeting strangers can be anxiety-inducing or fun or a mix of each, depending on your degree of introversion. An audience member, seated in the semi-dark, faced with actors usually feels quite safe (short of the fear of unanticipated participation), but when the performers are playing themselves and revealing sometimes disturbing features of their lives, you might feel some real-life discomfort. It’s less likely these days after nearly four decades of what was once disparagingly labelled “confessional” performance in the 1980s, but it’s a not uncommon feeling and one that in fact makes (let’s call it) “reality theatre” attractive, especially when it’s tied to a social, cultural or political issue or community that we have limited understanding of and for which we feel concern.

Shopfront’s Harness Ensemble of performers with a disability and the Australian Theatre for Young People have come together to make Dignity of Risk. In ATYP Studio 1, the multiracial, mixed ability group of 11 young women and men (possibly late teens to late 20s) stand or sit facing us in low light while we listen to their recorded voices in a stream of utterances, each no more than a sentence long, offering clues about how they view themselves and the world. Aptly, the first concern is with appearance, how they think they look and feel about being looked at. Some care, some don’t. The next time they speak it’s live and we begin to match voices with bodies and as more of these utterances are presented and with more detail and in occasional solo passages, we build a cumulative sense of each performer, not a complete picture, but enough to register dimensions of a personality from fragments of appearance, movement, information and interaction.

Ensemble, Dignity of Risk, ATYP/Shopfront, photo Tracey Schramm

Essentially, Dignity of Risk is a first meeting, and, if it stays with us, might affect our attitudes to the people these 11 actors represent to varying degrees. A true meeting would require our interaction with them and people like them. Perhaps that will come, and should, in an empathy-challenged Australia. These actors generously open up to us so that, in turn, we might be openly receptive and inclusive.

Litanies of “Don’ts” and “Wishes,” from the humble (“When am I allowed to get drunk?”) to the unusual (to be a 40-year-old out-of-touch-with-fashion dad, perhaps a desire for normality) and others reveal that those with and without disability share everyday anxieties and the weight of depression. We hear of suicidal impulses, bipolarity, the stress of a broken marriage and the hurt of racial prejudice and cruel utterances like, “If I’d been your parents I would have killed you at birth.” These are tempered with good humoured self-deprecation, amusing anecdotes and bouts of party dancing to James Brown’s artful electronica and Fausto Brusamolino’s cascading colours.

One of the strongest scenes comes late in Dignity of Risk as each of the actors jostles for a place in a hierarchy of disadvantage. The engaging and lanky Caspar Hardaker feels he’s been victimised for being a straight white male, which rouses a laugh from his comrades, but he returns to it with conviction, revealing the extremity of his depression. After itemising her considerable medical and other challenges, a relatively quiet Teneile English wryly declares herself the most advantaged because she’s got a very good, well-paid job. It’s a lovely swerve and comes out of a scene in which the actors are actually talking to each other rather than to us.

Another unusual moment features Mathew Coslovi standing centrestage and simply changing from his clothes into an identical set with an air of conviction about the rightness of the task. Riana Shakirra Head-Toussaint (a lawyer and disability activist) in a wheelchair and Jake Pafumi perform a striking role-reversal duet in which Pafumi first does the pushing but is soon pulled along by Riana and then rests on and arches out from her lap. Later, when the set’s soft curtain falls to the floor, Pafumi picks up one end of it and progressing across the stage, gently wraps it around himself in an act of unemphatic cross-dressing.

Ensemble, Dignity of Risk, ATYP/Shopfront, photo Tracey Schramm

Designer Melanie Liertz’ set comprises sleek black, reflective flooring framed by the semi-transparent curtains mentioned above. These are dreamily lit, falling away to reveal long narrow panels of firmer material splashed with dark colours, suggestive of a wider, perhaps tougher world, although the correlation isn’t clear, especially when the performers move slowly in and around this second curtain, stroking, lifting and letting the panels fall. Liertz’ design, Busalomino’s lighting and Brown’s tautly composed and rhythmically diverse score collectively complement the cumulative layerings that constitute the personalities of the performers. Margot Politis’ choreography has its moments — the wheelchair duet and pummelling fists and stamping in another scene and in Holly Craig’s solo — but hasn’t realised a consistent, simple vocabulary apt for the work, resulting in an unrevealing looseness in an otherwise tightly ordered production.

Holly Craig, who expresses her concerns about being able to look after her dog and knows that she has to be in care, affectingly brings home the complexity of the issues that drive Dignity of Risk. The production’s title is the same as the medical and social policy protocol “Dignity of Risk” which is about respecting each individual’s autonomy and self-determination (or “dignity”) to make choices for himself or herself, despite (“reasonable” is sometimes inserted here) risks. Sometimes Duty of Care clashes with Dignity of Risk, as in the case of sports people with disabilities.

The extent to which the performers with a disability other than Holly might be at risk had to be largely guessed at. Given the title of the work, I wanted to ask, what risks, physical, emotional or intellectual, might these people actually take to maintain or achieve dignity; but this issue is not seriously canvassed. Instead, the production asks us, at the very least, to listen and to accept the right of people at risk to dream, express and test their limits just as their fellow cast members without disabilities do.

While I felt that the notion of “risk” was insufficiently probed, that movement could have been more considered and the theatrically well-worn litany structure, while working well initially, limited a sense of conversation, Dignity of Risk nonetheless granted me a revealing first encounter with a fascinating group of strangers. Their frankness, moments of eccentricity, anxiety and passion and their determination opened me to their various worlds. Under Natalie Rose’s direction they seized the stage with fluency and confidence — that’s risk-taking.

–

Dignity of Risk, devised by Shopfront Harness Ensemble and Australian Theatre for Young People, director Natalie Rose, dramaturg Jennifer Medway, Mathew Coslovi, Holly Craig, Teneile English, Caspar Hardaker, Riana Shakirra Head-Toussaint, Steve Konstantopoulos, Wendi Lanham, Briana Lowe, Sharleen Ndlovu, Jake Pafumi, Dinda Timperon, set & costume design, Melanie Liertz, choreographer Margot Politis, sound, AV Design James Brown, lighting design Fausto Brusamolino, ATYP Studio 1, The Wharf, Sydney, 9-26 Aug

Top image credit: Jake Pafumi, Riana Shakirra Head-Toussaint, Dignity of Risk, ATYP/Shopfront, photo Tracey Schramm

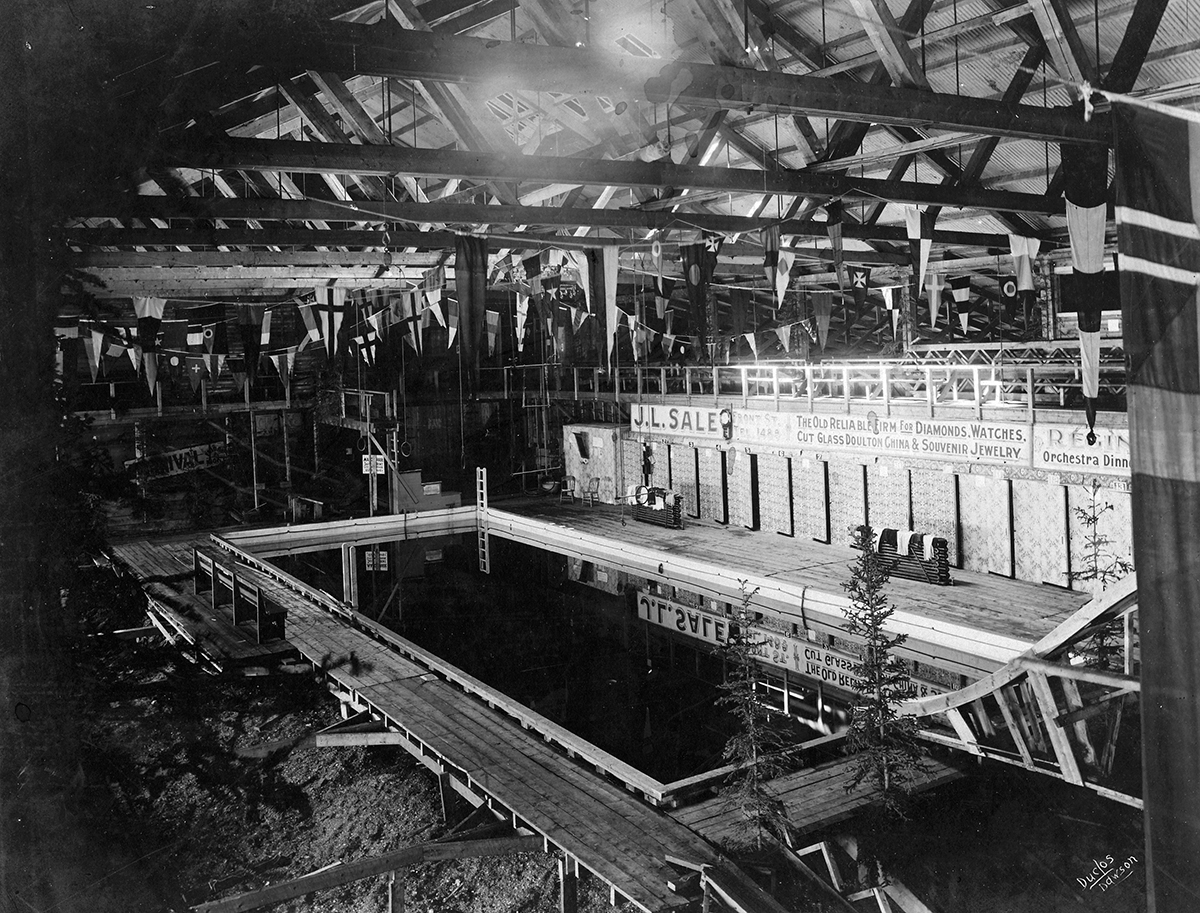

Two things born of fire preoccupy US filmmaker Bill Morrison in his new documentary: a city’s history and cinema itself. Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016) surfaces the archives of the photographs and early silent films from a chilly Canadian Gold Rush town to present a new vision of North American history and myth. The documentary follows Morrison’s earlier works montaged from rescued footage in varying states of decay and after being shown at the New York Film Festival last year, has finally entered the orbit of the Australian festival circuit, which has offered a select but fine collection of essay films this year.

First came Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro (2016) at Sydney Film Festival, which brought to life the words and spirit of James Baldwin to posit that the shame and responsibility for contemporary racism is on white people not black people — that white supremacy is not a blot on the surface of the USA but a brick laid in its foundation and a moral affliction for the dominant culture that makes black people its monster. Then at the same festival came a retrospective screening of For Love Or Money (1983), an almost-lost feminist history of women’s labour in Australia made entirely from archival materials. An exemplary and collectively authored work of the essay film genre, it was all the more striking given the absence of a continuous tradition of that strain of filmmaking in this country.

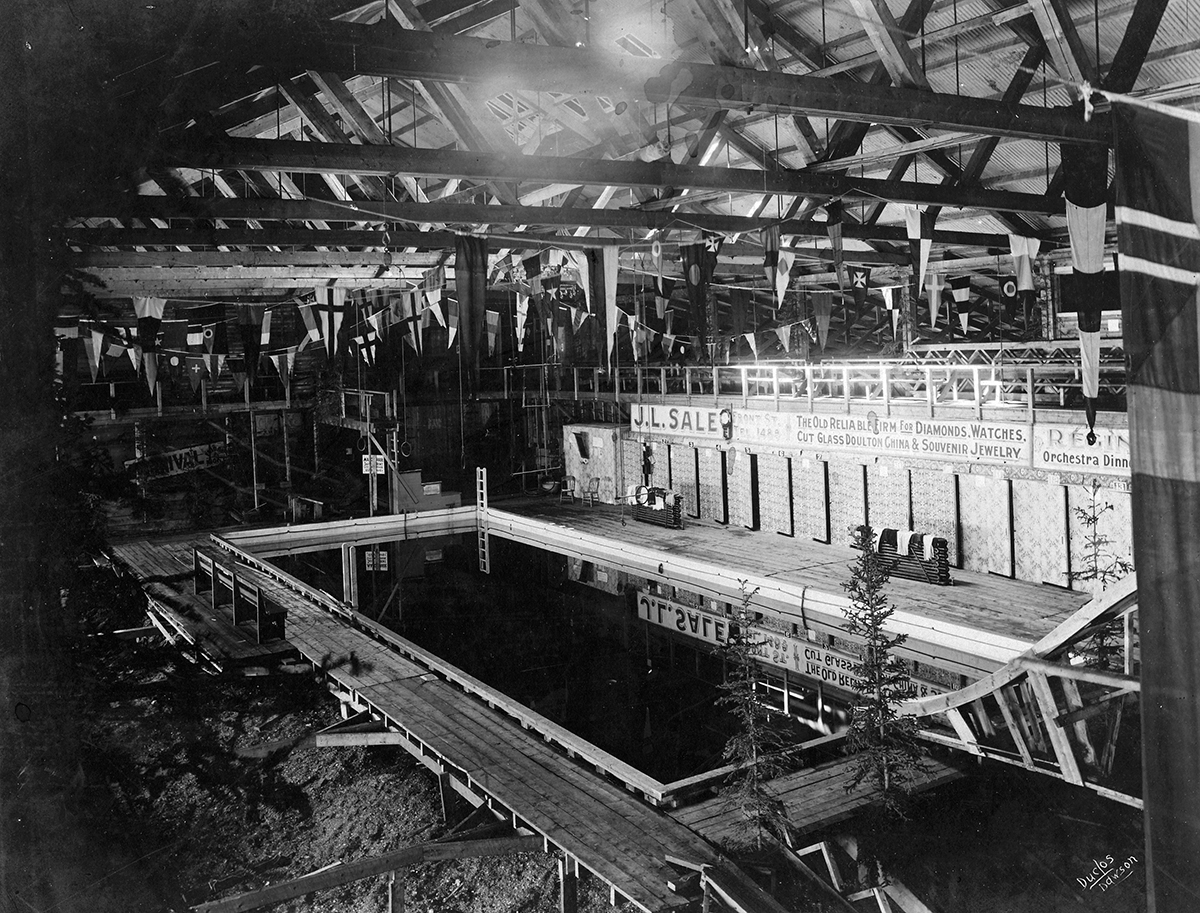

First Avenue in Dawson City (1898) courtesy of Vancouver Public Library, Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures

Dawson City: Frozen Time submerges itself in the archive to nudge to other parts of film history: it is in some moments a gold rush drama and in others a Western in the way that it summons an icy frontier, slowly encroached upon by tiny, impoverished, determined settlers. In Yukon, Canada, Dawson City was properly colonised in 1896 and experienced a fever dream of messy capitalist growth spiked by gold mining. For the final years of the 19th century, gold dust was the central currency traded in its brothels, bars and, yes, cinemas. Among the rickety buildings that sprang up in this period were theatres of silent films entertaining exhausted, drunken workers whose families had only just been sent for. Given the town’s remoteness, it lay at the end of the film distribution line: studios refused to pay for the cost of freighting cans of abundant — and dangerous — celluloid film back to California, and the town became a tomb for entertainment industry detritus.

Tonnes of reels past their economic use-by date were stashed in the basements of Dawson City’s frontier buildings, and were liable to burst into flame on account of their highly combustible nitrous base. As such, fire marked the foundations of both the town and early cinema: around once a year, until acetate stock was introduced, a nitrate fire would rip through the streets and colonisation would begin again. Cinema proprietors came to dump film reels by the tonne into the Yukon’s great ice floes: down the river they went, along with archived knowledge of the period’s early silent films.

Over the course of two hours, Dawson City: Frozen Time unfurls a slow-encroaching mystery to reveal the source of the visual material it uses: a self-reflexive discovery of a strange, surely impossible stash of celluloid, preserved in the Yukon permafrost and forever linking the concurrent birth of the gold rush, silent cinema history and the founding myths of this colonial town pitched so perilously in Indigenous snow. Along the way, we learn of Dawson City’s other connections to cinema: the film City of Gold (1957), documenting the Klondike Gold Rush, was the first to use the now-ubiquitous convention of zooming and panning over still photographs, laying the basis for Morrison’s own approach in form and aesthetic as director, writer and editor.

DAAA Swimming pool, courtesy Dawson Museum, Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures

It is of course extraordinary to think of the absence of any notion of cultural heritage in the early days of cinema: that film was so costly to make and transport, but would still be thrown into landfill or a river once its immediate economic value was spent. Nobody thought of keeping cultural objects for posterity. But Dawson City: Frozen Time is much more than a cinephile’s film. Bill Morrison ensures the inhabitancy of the region’s Indigenous people is quietly but tangibly felt, tracking moments in the life and death of Chief Issac of the Han-speaking Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in nation, Mayor of the township of Moosehide, where his people were dislocated, five kilometres downriver as Dawson City ballooned in population. The fragility and waste of the colonial project becomes a ghostly presence throughout the documentary, with overhead photographs later in the film showing how mining has carved the Yukon landscape into gloomy, grey pits of ever-greater scale. The ever-changing geography that cinema crosses becomes a way for Morrison to hint at boundless thematic rivers, depending on what viewers themselves bring to the viewing.

Dawson City: Frozen Time’s most intense quality is its richness, both visually and historically. Every little part of it is inflected with the weight of more than a century of time, every frame full with Morrison’s distilled intentionality. It is a long film, but to spend 120 minutes with it is to be pulled directly into its quiet, largely greyscale world. The flickering, floating footage on which it is almost completely founded, developing from black-and-white to colour, from silence to sound, doesn’t just lend the film its spectral feeling, but writes a new, modest chapter in the much-mythologised story of cinema and frontier America.

–

Dawson City: Frozen Time, director, writer, editor, producer Bill Morrison, producer Madeleine Molyneaux, composer Alex Somers, Melbourne International Film Festival, Kino Cinema, 13 Aug; Sydney Underground Film Festival, Factory Theatre, 17 Sept

Top image credit: Dorothy Davenport in Barriers of Society (1916), Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures

You cannot press ‘pause’ on a sound. Well, you can, but once paused, it is no longer the same sound. The duration, and thus the timbre, the tone, the effect of a sound, is altered. Indeed, if paused, a sound simply becomes a void. An image can be frozen in time, lifted out of the many images around it and examined in detail, but a sound cannot; pressing ‘pause’ on a tape player will only create silence, or perhaps the gentle humming of an idle speaker.

Michel Chion often writes about pausing sounds, and the way that sounds transform in different conditions, different scenarios. A French writer, composer, filmmaker, and sound theorist, it is impossible to capture Chion’s body of work in a single essay, impossible to cover everything of interest in a single conversation. He refuses to call himself an authority, but his output would suggest otherwise, as his books, and their translations, are widely read and taught at universities across the globe. In Sound: An Acoulogical Treatise, recently published in an English translation by James A Steintrager, Chion writes that “observing sounds is like observing clouds rapidly streaming.” This nod to the ephemerality of nature evokes a world across its spectrum, from tranquility to wild havoc. Sound is always coming and going around us, constantly shifting and forming new shapes and reverberations. It is respiration, it is the ebb and flow of the sea, an introduction and a disappearance, a negotiation of harmonic spectra. It is both natural and artificial, a product of deliberate design and construction.

Sound exists in time, and so always exists. Chion’s expression “frozen sounds,” he tells me, “considers that it’s impossible to freeze sound because it is in time.” He is in Melbourne for a series of performances and lectures in late August, curated by Liquid Architecture, the Melbourne International Film Festival and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Of keen interest to him, as well, is the texture of recorded sound, something he began experimenting with decades before the digital renaissance. As situations, surroundings and perspectives change, so too do the sounds. Listening back to the recording of our conversation, which took place in a busy, and noisy, café in Melbourne, I’m aware of the discordance between experience and recording. Joined by his wife Anne-Marie Marsaguet, we were surrounded by — as Chion might call it — “bruit,” a French descriptor for anything that interferes with our aural receptors, that we don’t necessarily want. (The French language can be more descriptive, he says to me.) Certain sounds are enlarged and others dulled in a distracting litany behind our voices echoing back to my phone’s recording point. In one sense, it’s unpleasant, but there’s much to be gained from a close study of it. I hear a bird chirping loudly somewhere above us, and remember a particular moment, as Chion mentioned Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and gestured to the sound, smiling.

Michel Chion, Joel Stern, photo Keelan O’Hehir

“If I had to describe me, it’s difficult,” says Chion. “I would say that I am a searcher.” He also admits to being a writer of books, an historian and an observer of phenomena. Observing is a neutral term and a multisensory one, not restricted by Western civilisation’s typical ocular bias, but importantly not excluding sight. “I am trying to be a scientist. A scientist of listening,” he says, but later he seems to reconsider this, and rephrases. He is an observational scientist.

For Chion, the experience of seeing and listening together is an essential part of everyday life. And this life experience can be found in the cinema, the world refracted on the silver screen. These experiences are about being attuned to the spaces and sounds in the audiovisual, polyphonic expanse around us. “We cannot, from morning to night, be actively listening. We have to be sensitive [to what’s important].” But it’s a fact, says Chion, that the inner ear redirects itself towards the dynamic sound phenomena around it. A film’s sound, emanating from speakers, only truly takes place when it reaches the ears, something he states in Film: A Sound Art, his book translated into English in 2009 by Claudia Gorbman.

Chion’s performance in Melbourne on 17 August included the world premiere of a work of musique concrète, The Scream, and was followed by his famous Requiem and the 80-minute Third Symphony, the most sensorially dynamic of his three concert pieces that enlarge the visual space of the screen with sound from surrounding speakers. In Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, also translated by Gorbman, he writes, “Cinema is not solely a show of sounds and images; it also generates rhythmic, dynamic, temporal, tactile and kinetic sensations that make use of both the auditory and visual channels.”

His compositions aim to create this kind of cinematic affective sensation, too. By contrasting the meaning of words with images and sounds, he creates a fluid shift between alignment and chasmic disagreement. “What is important for the experience is totality,” he says of these compositions. “You can, with an orchestra, or with a movie, rebuild a soundscape. But it’s completely artificial, made with different sounds, at a different time.” He thinks of his compositions in the same way, as new experiences. “As a composer I define musique concrète as an art of fixed sounds, but fixed sounds are not the recording of precise sounds, pre-existing sounds. They are new objects.”

Michel Chion, Anne-Marie Marsaguet, photo Keelan O’Hehir

The sound of David Lynch

Chion has been a key thinker about these soundscapes for decades and even his older writings remain relevant. With this in mind, I ask about the soundscapes of someone with whom he is very familiar.

“There are extraordinary moments, and it’s very experimental. The most important thing in David Lynch’s case, is that he has a feeling of space and time,” Chion says of Twin Peaks: The Return. “And if you have a feeling of space and time, you can express it with time and image.” He describes the opening scene of Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) that he uses while teaching, where husband and wife, Fred and Renee (Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette), engage in slow conversation, with deliberate pauses in their dialogue. For Chion, the scene is an image of eternity. Moments that appreciate time in this way — as a sort of anti-narrative — are becoming extremely rare. “Today on the TV there are no more intervals, because of commercials and with remotes, people change channels. That people keep going to the movies, especially slow movies, is in my opinion to rediscover what is important in an interval. So, even if in David Lynch movies there were no strange situations or no strange sounds, his sense of tempo and space would be very strange, very specific.”

It’s clear that this sense of temporal experience is key for Chion. Throughout our conversation, the concept he returns to the most is not sound but time. Waiting, he says, is an essential part of our existence and we need to appreciate the interval. Slow down and observe the world; he and Marsaguet smile. “To let the cosmos exist.”

–

Melbourne International Film Festival, Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, ACMI, 16 Aug; The Audio-Spectator Concert, ACMI, Melbourne, 17 Aug; Presented by Liquid Architecture, Melbourne International Film Festival, ACMI and Institut Français.

Top image credit: Michel Chion, photo courtesy the artist

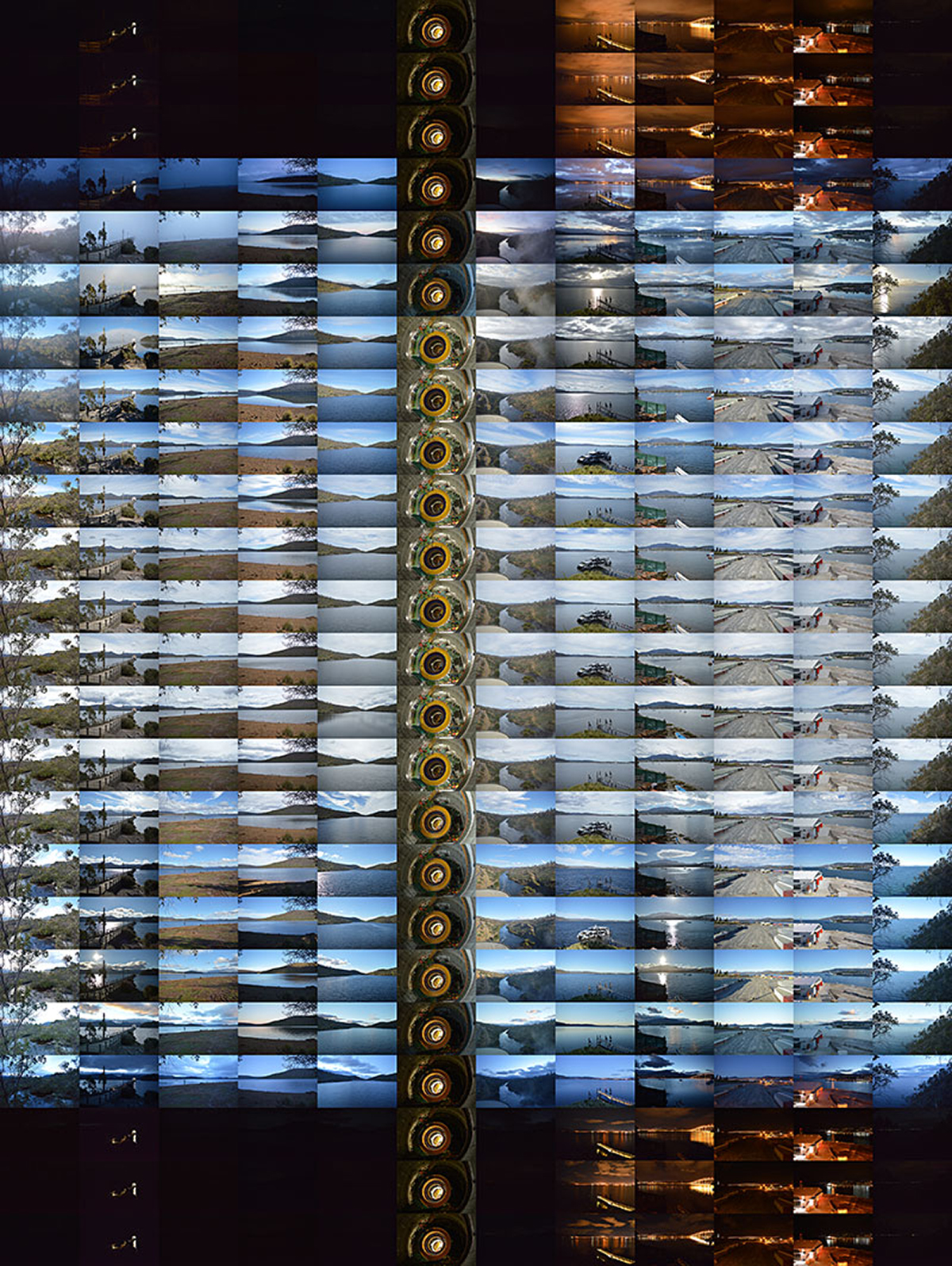

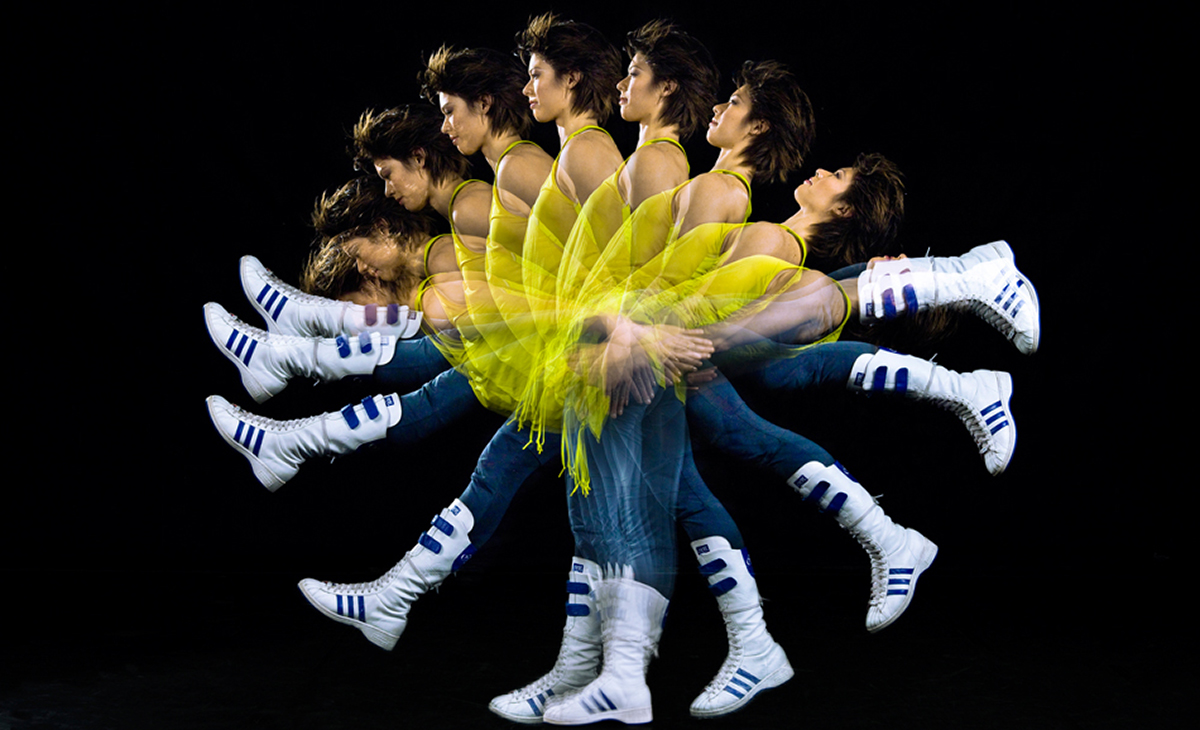

Rhiannon Newton’s Doing Dancing makes me think about being, through time. Given her interest in the way dance “insists on disappearing,” as the artist writes in her program note, it feels appropriate that the work seems to dissolve in my grip, prompting questions and ideas that too have a delicious way of slipping through my fingers.

The work’s audiovisual installation is on show at Firstdraft gallery for several weeks, punctuated by three performances and/or making sessions that generate new material for it. I attend two of these. During one, Newton works alone, with Benjamin Forster operating recording and playback software he has built; during the other, she works with Forster and six other dancers.

The sessions follow a repetitive, almost circular structure: a performer reads a piece by Gertrude Stein, and then improvises a dance for a set period. Both the reading and the dance are recorded, and the video of the dance is projected in real time onto a nearby wall. This process is repeated over and over (the Stein text almost identical each time), by different dancers or, in the solo session, by Newton herself. And with every repetition, the recordings of previous iterations are also present: we hear each reading over (or alongside) audio recordings of previous readings, and see each presently unfolding dance projected onto previous dances.

The Stein text is a written portrait of Isadora Duncan, edited for this work by Newton. It is an extended cascade of phrases that meditate on being, oneness, likeness and dancing. The phrases dovetail and overlap; they sound like each other but bifurcate constantly, disorienting you just at the moment that you think you will figure out “where you are.” While the human body is so easily (and widely) understood as something solid and bounded, this text makes me ponder whether the persistent existence of a body through time might actually involve an infinite number of unique moments, and an infinite number of potential movements, actions and expressions, held tenuously together.

Doing Dancing, Rhiannon Newton, image Benjamin Forster

Watching the dancers improvise their way playfully and attentively around the circular rug laid out on the cement floor, thinking-and-moving, thinking-through-moving, I find myself thinking about moving as a process of going forwards through time — of always leaving a significant ‘now’ behind you. Watching the layered video, in which so many Rhiannons spill across and away from each other, and hearing all at once the eight different ways she has spoken a particular phrase, I reflect on the single body’s ability to trace a multitude of potential dances (and pronunciations of a word) over time.

Such ideas, I gather, are persistently interesting for Newton: her earlier work, Assemblies for One Body (2011), explored what “remains” of dance as we move forward through time, and how repeating a dance might allow us to examine that. The later Bodied Assemblies (2014) explored, among other things, the body’s capacity to be uniquely itself (to be radical, different), and equally its capacity to be like something or someone else.

“Dance insists on disappearing,” she writes, and indeed, over time, the accruing, translucent video layers grow wafer-thin. While the projection initially feels almost as solid as another physical place, in which the present dancer is in the company of one or two past selves, it transforms layer by layer into a vast and shimmering retrospective that vanishes even as it expands.

Being is so elusive, so diffuse, I marvel. And yet, watching Newton or Julian Renlong Wong or Miranda Wheen dance in the flesh, in the waning afternoon light, shouts from a nearby sports match drifting in through the open window, it strikes me that, just now, a dancing body doesn’t feel complicated at all. These dancers, who perform as themselves — who are always themselves, here with us, doing dancing — possess roundness, weight, hair and breath. They feel solid, significant, and all of this feels wonderfully straightforward.

Doing Dancing gives ample space to such double perspectives. It also allows for experiences like the one I have at the end of the group performance, when the room breaks into applause and I get the strange feeling that I don’t know who I’m clapping for — or, that I’m clapping for no one in particular. Of course, on one level I know. But it feels like, in doing this work, the artists are facilitating the emergence of something else: something that is at once all of them, and none of them. The work has an inbetweenness, maybe even a vanishing, at its centre. And even so, it makes dancing, and the ‘here and now,’ feel entirely weighted, persistent, sensuous.

–

Doing Dancing, Rhiannon Newton with Benjamin Forster, group performance with Brooke Stamp, Lizzie Thomson, Ivey Wawn, Miranda Wheen, Julian Renlong Wong, Trish Wood; Firstdraft gallery, Sydney, 2-25 Aug

Top image credit: Doing Dancing, Rhiannon Newton, image Benjamin Forster

Salt, like memory, preserves through a process of permeation — altering the structure of its ‘host’ while acting to retain some essential, singular quality. In the landscape of Sonya Lacey’s By Sea, salt fills the gaps and fissures opened up by the erosion that it has set in motion. The architectural space through which the camera glides shows the cumulative result of this process. Each passageway is translucent, constructed of cast salt that appears blemished and brittle when in close-up and in focus.

This imagery sits in uneasy accord with fragmentary narrative pieces afforded to the viewer by voice-over. These shards of information refuse distillation, their loose ends and peculiar tangents circuitously housing the world of the film within a larger set of metaphysical dimensions. We hear of glimpses of life inside a seaside apartment complex where each building forms a letter shape, so that an aerial view elicits the phrase “Par Mer.” We are told that the building is less legible on the inside, that no one knows for sure what it might be like to inhabit anyone else’s living quarters. Despite these challenges, the narrator says, “We resolve to share our partial information.” In these instances, the work’s eerie sense of profundity amplifies such notions beyond the geometric specifics of any one apartment, just as it echoes the conditions and confines of our subjectivity as individuals.

By Sea was inspired by the writings and short films of New Zealand poet and experimental filmmaker Joanna Margaret Paul, which, like Lacey’s work, often take the form of intimate meditations on the experience and minutiae of place. Such a focus is apparent in a 1985 issue of Cantrills Filmnotes, in which Paul wrote that “in a landscape or garden one discerns messages from within.”

Initially, the message-writ-large seems to elude those inside Par Mer. But the specifics of interiority — the slight tilt, the curved walls, the sound of a Supremes cassette, the salt in the flaws — cumulatively come to contain something that exceeds the reach of a two-word phrase read from above. We are told that coastal attrition is threatening to sweep Par Mer off the map. Yet it seems that if this were to eventuate, or if it already has, the granular particulars will preserve, for a select few, what it was like to experience their unique reality from within. Elyssia Bugg

Three guitars are held aloft, one played by the musician’s tongue, and all of them are blasting out Acid Mothers Temple’s euphoric brand of psychedelia. It’s the kind of blistering sonic lather that is rarely encountered at 6pm on the stage of Melbourne’s State Theatre. But tonight, and for a majority of Supersense’s “festival of the ecstatic,” the theatre and the Arts Centre that houses it, are doing their best to portray a different kind of space — one that is transformed and transformative.

Audiences descend into the belly of the Arts Centre via stairwells and passageways that gurgle and heave with a soundscape that anthropomorphises the building, suggesting digestion. Yet what is being absorbed, and by whom or what, is a question that arises repeatedly over the festival’s weekend.

Memory Field

A thematic concern with dream, memory, the alien and otherworldly pervades the Supersense program. Amid these, and perhaps despite its name, Memory Field feels very present. A duet between Bangarra dancer Waangenga Blanco and PVT drummer Laurence Pike, Memory Field begins in a haze of static and a pool of light. The stage is divided in two, Blanco caught in the spotlight on one side, Pike sculpting the soundscape from behind his drum kit on the other.

Blanco incorporates elements of traditional movement from the Torres Strait in his choreography. This vocabulary is woven through the tormented lyrical style, as the dancer makes angular contact with the floor to crawl, roll and claw his way around the perimeter of the light’s broad circle. Over the course of the performance, his charting of the light’s limits turns its initial enquiring focus outwards, the movement actively labouring beneath the weight of increasing distress.

Blanco’s circular journey is met beat for move by Pike’s restless score, which teeters, staggers and shudders through the Playhouse. As the circle, or memory field, finally tightens around Blanco’s writhing body, a tightness takes hold of Pike’s obstinate patter, uniting the performance elements in a claustrophobic embrace.

The way in which the artists sustain this seamless tension gives the piece’s exploration of memory (perhaps of ancestral culture) an ominous quality. This in turn reflects the oppressive cyclicality embedded in the act of remembering when the past itself is unforgettable. In a way that is uncommon throughout much of the festival program, Memory Field thus refuses transcendence. Instead it sets past and present in a deadlock, and holds the audience at this impasse, in a manner both challenging and memorable.

Lullaby Movement, Sophia Brous with Leo Abrahams and David Coulter, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino

The Dream Machine

Touted as “the world’s first work of art you look at with your eyes closed,” The Dream Machine seems to come with the implicit promise of upending artistic convention. Conceived in the 1960s by Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and William S Burroughs, the work was originally intended to transport the participant into the phantasmagorical, using a record player and flickering light.

For Supersense’s reimagining of the work, an ensemble of artists from across the program, including guitarist Dave Harrington, saxophonist Arrington de Dionysio, harpist Zeena Parkins and the festival’s curator Sophia Brous, have been assembled to provide a live soundtrack for mass delirium. The audience is sprawled across the stage of the State Theatre, eyes closed, when the strobing begins. The music crests and light explodes across the hallucinatory field behind my eyelids. Hot shades of orange and pink burst and blur, following the blazing pace and squeal of Dionysio’s saxophone veering across the multi-instrumental clamour. I surrender to the tide of colour and sound, slightly nauseated, but mostly thrilled.

We are given brief respite when Parkins and cellist Oliver Coates perform an interlude that is striking for the sudden sparsity that is felt sonically and visually. This transitory lull achieves a sense of subtlety otherwise lacking in the performance. For while The Dream Machine’s hallucinatory powers are novel, its dynamics feel less innovative, the score relying heavily on two distinct peaks that intensify the visions one sees while listening. These render the work somewhat predictable, with the audience anticipating the return. That said, as I open my eyes to the sound of Brous muttering poetry, her breath catching on the edges of the score as it winds down, reality feels just a little too sharply focused, suspending a desire to keep dreaming in its wake.

The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino

The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane

We return on Saturday night for a different kind of transcendent experience. Again, we sit on the State Theatre’s stage, but this time the aesthetics of ecstatic intimacy are challenged by the numbers in attendance. The space’s transformation into a long hall hemmed in by white curtains forces disgruntled patrons to spill out beyond the peripheries of the space.

The overcrowding is mostly forgotten as the Sai Anantam singers vividly animate the legacy of Alice Coltrane, musician and founder of the ashram from which they’ve travelled. During the performance, transitions from prayers on high to deep, gospel grooves occur repeatedly, each time drawing the listener a little closer to a conception of the divine that intertwines the cosmically vast with the exquisitely personal. This feeling of totality is encapsulated in the breadth that the synthesiser’s ascending glissando lends to chants of victory, peace and bliss.

However, the Arts Centre’s limitations continually impede inclusivity. Invitations are extended for the audience to make use of the songbooks they are handed on entry and the performers’ sound levels turned down to allow the voices of the audiences to fill out the arrangements. But by design, the space favours loud, grandiose and amplified sound, muffling audience input. Consequently, when a handful of people do take up the invitation to sing, their unamplified voices fail to rise up in elation as they would, one assumes, in Coltrane’s ashram.

Arts centres like Melbourne’s only function efficiently when their Western, metropolitan bias is the default setting. A festival like Supersense directly and indirectly problematises this notion, as its access-all-areas approach denies the space any claim to passivity. Yet in such an initiative, the most effective interventions tend to be ones in which the performers instigate subversion, while the arts centre plays itself. Where an artist like Keiji Haino benefits from being able to pump his screeching sonic miasma into every acoustically submissive corner of the Playhouse, the songs of Alice Coltrane are lost in the ungainly process of imitation that the space undergoes in trying to create context for work that sits outside of its cultural ambit.

In this way, it’s unfortunate that the crowd seemed resistant to joining the Sai Anantam singers in song, but it’s also unsurprising. One doesn’t enter a spiritual state of ecstasy through a side door or the back stage. Such a reaction relies on more than externalities. It must originate, primarily from within.

Deborah Kayser, Peter Knight, Matthias Schack-Arnott, Overground program, Supersense 2017, photo Mark Gambino

Overground

This is perhaps why Overground, the “festival within a festival,” most closely resembles something of the ecstatic. Featuring performers from inside and outside the main program in an afternoon of collaborative improvised works, the festival transpires in the Arts Centre’s foyers. In these spaces, encounters between artists and works may be accidental and ephemeral, the results unexpected and electrifying.

Such is the case in an hypnotic collaboration between Deborah Kayser, Peter Knight, Matthias Schack-Arnott and Cleek Schrey. Schrey, who on Friday night had conjured the falling walls of biblical Jericho through the refrains of Appalachian folk song, here seems to use his instrument to summon the demonic. The tortured whining and sighing he elicits from his hardanger fiddle urges on Kayser’s wraithlike moans, so that for a time, the scene wavers on the brink of becoming a séance.

Curated in collaboration with The NOW Now and Liquid Architecture, Overground eschews assimilation of any one element into another. Instead, it instigates fluid, responsive exchange between the artists, the audience and the site’s specifics. In doing so, the pretensions of the Arts Centre and its audience are dispersed, opening both up to the possibility of rapture.

–

Supersense, Festival of the Ecstatic, curator Sophia Brous; Arts Centre, Melbourne, 18-20 Aug

Top image credit: Memory Field, Waangenga Blanco, Laurence Pike, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino

The APRA-AMCOS and Australian Music Centre’s 2017 Art Music Awards ceremony at Sydney’s City Recital Hll engendered a genuine sense of occasion, opening with a richly expressive and welcoming didjeridu performance by Mark Atkins and closing with an affecting performance of “Koolja” by the stellar Narli Ensemble comprising Stephen Pigram (voice, guitar), Errki Veltheim (violin), Stephen Magnusson (guitar), Mark Atkins (didjeridu), Tristen Parr (cello) and Tos Mahoney (flute).

AMC Chair Genevieve Lacey spoke of how “humbling and fortunate” it is to be a musician and to “reveal what tears at us” in troubling times in which, she says, we should turn for inspiration to the recent Uluru Statement from the Heart. She paid tribute to outgoing APRA-AMCOS CEO Brett Cottle, who emphasised the importance of experimentation and community and in turn praised as “selfless and hardworking,” the indefatigable AMC CEO John Davis, whom other award winners also praised.

Narli Band, Art Music Awards, 2017, photo Tony Mott

Another champion of Australian music, ELISION artistic director and managerial force to be reckoned with, Daryl Buckley, received the Award for Excellence by an Individual. For some 30 years, he has promoted Australian music-making and composition principally by sustaining the ELISION ensemble, which he described as “a family of equals,” and expanding its international reach, at times against considerable odds.

Many compositions, including three operas, by the profoundly inventive Liza Lim have been premiered by ELISION. This year she won two awards, including Instrumental Work of the Year for the ecologically and anthropologically-inspired How Forests Think, which the ensemble thrillingly premiered at last year’s Bendigo International Festival of Exploratory Music (BIFEM), featuring sheng player Wu Wei and conducted by Carl Rosman. The work is dedicated to John Davis.

Lim also won the Vocal/Choral Work of the Year for the opera Tree of Codes premiered by Ensemble MusikFabrik and Cologne Opera, conducted by Clement Power and directed by Massimo Furlan. Excerpts from the production reveal surreal staging (including something of the heft of the score). Lim spoke of the joy of being able to produce “a work of scale,” and, at her reckoning, “one every seven years.”

Marshall McGuire played Lim’s Rug Music, which draws deeply on the harp’s resources, while cellist Tristen Parr strikingly played Cat Hope’s Shadow of Mill (1st movement) with a bow in each hand.

Melbourne’s Speak Percussion won the Award for Excellence by an Organisation, pianist Peter de Jager (who impressed so much with his monumental Xenakis concert in BIFEM 2016) received the Award for Performance of the Year, and Lyle Chan was awarded Orchestral Work of the Year for Serenade for Tenor, Saxophone and Orchestra to words by Benjamin Britten about a pre-WWII relationship.

Tura New Music won the Award for Excellence in a Regional Area for its unique remote WA touring and development program. Artistic Director Tos Mahoney spoke of the importance of “learning, not just delivering” in the organisation’s contact and collaborations with Aboriginal peoples.

Ten Part Invention, Art Music Awards, 2017, photo Tony Mott

One winning group stood out for the highly unusual nature of their collaborative achievement. The Award for Excellence in Experimental Music went to Clocked Out (Erik Griswold, Vanessa Tomlinson) with Bruce and Jocelyn Wolfe, who accepted it on the night, for The Piano Mill Project. Sited near Stanhope in Queensland, it’s described on the project’s website as “a square structure clad in copper, designed by architect Bruce Wolfe and purpose-built to house 16 pianos — eight on the first level and eight on the mezzanine. The walls consist of large-scale louvres, which can be opened and shut to alter the Mill’s acoustic.” Griswold has composed a score for the collective pianos which are of various ages and conditions. You can see the Mill and hear its distinctive sound on the project’s website.

Jazz drummer and until recently leader of Ten Part Invention, John Pochée received the Award for Distinguished Services to Australian Music. Peter Rechniewski’s glowing tribute, a short documentary and the artist’s speech revealed not only his innovations and his democratic spirit but also a life in which Pochée could happily combine playing exploratory jazz side by side with working for club bands and for visiting artists like Shirley Bassey, for whom he was a favourite. This segment of the evening gave us a fascinating glimpse of Sydney cultural life from 1950s clubs El Rocco and Mocambo to Pochée’s 1986 creation of Ten Part Invention — in which everyone was a composer — and on to the present with the band’s current lineup paying tribute to Pochée with a performance of And Zen Monk, composed early in the band’s career by Roger Frampton, embracing its quickfire subtleties and executing it with big band verve.

Daryl Buckley, Art Music Awards, 2017, photo Tony Mott

Andrea Keller won the Award for Excellence in Jazz and performed her “Darest Thou Now” with impressively supple singing from Gian Slater, while Tom O’Halloran won Jazz Work of the Year for the furiously complex album Now Noise, performed on CD by Memory of Elements.

These and other awards given out on the night collectively illustrate the wellbeing of adventurous Australian music-making across forms, cities and regions, paying tribute to the durability and influence of long-term contributors like John Pochée, Daryl Buckley and ELISION, Liza Lim, Clocked Out, Speak Percussion and Tura New Music who have engendered a new Australian musical landscape. The 2017 Art Music Awards, in a crisp two-hour ceremony with bravura performances curated by Gabriella Smart, did them proud.

Find the full list of awards here.

–

APRA-AMCOS, Australian Music Centre, Art Music Awards 2017, City Recital Hall, Sydney, 22 Aug

Top image credit: Liza Lim, Art Music Awards 2017, photo Tony Mott

Belvoir’s Hir (image above) is a viscerally funny and deadly serious account of an imploding nuclear family reeling from the impact, among other things, of a transgender teenager. It’s a perfect parable for our times. After focusing on graduate and postgraduate artists in recent weeks in our ongoing Arts Education & Training Feature, we turn our attention to new works made by academics who are prominent artists, successfully practising from within and beyond the academy. Professor Cat Hope of Monash University talks with RealTime about the innovations that underpin her new opera, Speechless, and Dr Karen Pearlman of Macquarie University, discusses her new film about a pioneering editor, Woman with an Editing Bench, part of the filmmaker’s research into editing and cognition. Also in this edition, reviews of a cluster of bold productions — Hir, The Rape of Lucretia, Tectonic and The Hamlet Apocalypse — and Dan Edwards expresses doubts about the VR revolution. Not least, we commence our series of previews of the much anticipated 2017 OzAsia Festival.

–

Top image credit: Richard Whalley, Greg Stone, Helen Thomson, Hir, Belvoir Street Theatre, photo Brett Boardman

Chloe Wong & Dance Lab

As part of the 2017 OzAsia Festival, Hong Kong dancer, dance teacher and choreographer Chloe Wong will be one of 11 choreographers from Australia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore undertaking a five-day residency, titled Australia-Asia Dance Lab, at LW Dance Hub in the Lion Arts Centre, Adelaide. Under the overall guidance of acclaimed choreographer Leigh Warren, the residency will enable participants from diverse backgrounds to collaborate in an experimental dance laboratory, and audiences will be offered the unique experience of being able to see them exchanging ideas and developing work together. I recently spoke with Chloe Wong in Hong Kong.

A 2006 graduate from the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts majoring in Modern Dance, Wong undertook a Masters degree program in the US and has extensive experience as both dancer and choreographer. Her solo and ensemble works have been performed in Asia, Europe and America and she is engaged in a three-year exchange in Japan.

Wong has a distinctive often theatrical approach to choreography, making extensive use of props and dialogue. In Heaven Behind the Door (2014), the dancers use an overhead projector to shine a beam of light through a glass bowl around the darkened stage, focusing the image of shimmering water over other dancers and onto the stage backdrop to create a visual effect that suggests a watery searchlight. The work was developed in 2014 at the time of the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. Demonstrators carried yellow umbrellas and the protest extended more than two months. “It moved me a lot,” says Wong, having witnessed many ordinary people become very vocal and protective of their freedom, confirming her belief that if people act to protect their own space and identity, they can be very powerful. Hong Kong is a society in transition, which raises the question of identity, an important theme in Chloe Wong’s work, especially when it’s repressed, as wittily demonstrated in the 2012’s The Red Cage, performed and choreographed by Wong, conceived with art director Moon Yip and subheaded “NO Brainwashing!”

Chloe Wong likes to work with other dancers in exchange programs, acknowledging each participant as an individual and what they bring to a workshop. Her own work, she says, is about enabling every individual to express their beliefs, with sharing an important part of the process. Her choreography develops organically, evolves over time and may be redeveloped with each new production.

Having previously worked with Australian dancers, Wong is excited to be doing so again. The other choreographers in Dance Lab are Alison Currie, Richard Cilli, Natalie Allen and Lina Limosani (Australia), Victor Fung (Hong Kong), Yu-ju Lin, Kuan-Hsiang Liu and I-Fen Tung (Taiwan), and Christina Chan and Ricky Sim (Singapore). “You just don’t know what will happen in the workshop… it’s the same as life,” she says.

As there is no plan to create a finished work or present a final performance, Dance Lab is an experiment without a predetermined outcome, and thus places no constraints on how the 11 participants might interact over the five days. At the end of the Lab, the artistic outcome will be the sharing of ideas between the participants. Wong suggests that working with other dancers “is a challenge, like making friends,” and she has no specific plans for the residency, preferring as she normally does to work spontaneously with the others involved.

Given Dance Lab’s open-ended, exploratory nature, offering such a workshop is a courageous innovation by the OzAsia Festival, but one optimistically supported by numerous agencies suggesting expected benefits for the contributing countries and their artists in the long-term.

As well as being able to visit the Dance Lab workshop, the public are welcome to attend a public discussion (details below).

Dr Wilfred Wong Ying Wai, Hong Kong Arts Development Council

Collaboration and cultural exchange are central to the OzAsia Festival. In 2016 the Adelaide Festival Centre signed a memorandum of understanding with the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC) to provide for shared programs to be delivered in 2016 and 2017. Hong Kong choreographers Chloe Wong and Victor Fung, new media artist and composer Gaybird and writer Dorothy Tse appearing in OzAsia 2017 are supported by HKADC.

I spoke to HKADC Chairman Dr Wilfred Wong Ying Wai, who emphasised the importance of enabling collaboration between Hong Kong artists and artists in other countries. He suggested that, in a world where artists collaborate, “it is important to have a wider network cultivated for Hong Kong as a whole… It is not just showcasing how good we are, it is also helping our artists to go to the next level… OzAsia has a very special meaning because it is a festival that really focuses on Asian art.”

Dr Wong noted that there has there has been much development in the arts in Hong Kong over recent years. “There is more of an attempt to identify who we are. In the past, all our artists are very happy to just go along with [for example] classical western music and do their best and hopefully be the best … But now, in the last 20 years, there is a search — what is local, who do we represent? What is the Hong Kong identity? There are a lot more creative works emerging in this area, particularly in the visual arts and dance.” He suggests that Hong Kong’s significant artistic development reflects a change in social values: “We have become much more artistic and cultural. We know that enjoying life is as important as making a living.”

–

OzAsia Festival: Australia-Asia Dance Lab, open workshop, 10.30am-12.00pm, Tue 26-Sat 30 Sept, 1.00–4.30pm, Sat 30 Sept, Lion Arts Centre; public forum, The Mill, Adelaide, 5.30 pm, Fri 29 Sept

Australia-Asia Dance Lab has been jointly funded by the Government of South Australia, Arts SA, DanceHub, The Mill, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, Culturelink Singapore and the National Arts Council Singapore.

Chris Reid visited Chloe Wong and Dr Wilfred Wong Ying Wai in Hong Kong courtesy of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council and the Adelaide Festival Centre.

Top image credit: Chloe Wong, The Red Cage, 2012, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

American playwright Taylor Mac’s Hir moves relentlessly from seemingly low farce to near tragedy, blessedly without a gun in sight, but with a needy young soldier returned from Afghanistan seeking a hero’s welcome and patriarchal order. He’ll get none of it. His working class family has changed, possibly America too.

The apparent chaos that greets him and us — an ordinary loungeroom and kitchen epically awash with scattered clothes, rubbish and unwashed dishes — is in fact a new order. The audience gasps, the ex-soldier, Isaac (Michael Whalley), screams and subsequently vomits at every instance of change. His father, Arnold (Greg Stone), appears to be a cross-dressing clown who can barely speak. His mother, Paige (Helen Thomson), has abandoned domesticity and mastered the lingo of feminism and LGBTQI politics, wielding it with a mix of wicked panache and amusing uncertainty and allowing Mac to satirise aspects of queer rhetoric, including that ever-lengthening acronym.

Worse, Arnold, who used to beat his wife and children, has had a stroke and is subject to Paige’s vengeance — dressed as a woman, fed mush, hosed down and kept cold with the aircon on (Paige’s taming of the stink of male sweat). There might not be a gun in Hir, but the competition over the control of the temperature is dangerously akin to its threat. Worse again for Isaac, his sister is now transgender Max (Kurt Pimblett), hence the play’s title, Hir, crossing his and her, and the injunction that Isaac use ‘zee’ as the preferred pronoun for Max (the arguments about transgender identity are an education). Can Isaac adjust to this new domestic order, how viable is it, especially for Max, and where does Arnold fit in, if at all? These are the questions that Mac’s characters must face as the greater part of the play unfolds and darkens between explosive bursts of comic conflict.

Although it’s clear that patriarchy has no place in this household (Arnold’s debilitating stroke is as symbolic as it is actual), the complexities of gender orientation and typecasting will endure. Paige notes that with Isaac’s arrival male moodiness is on the rise and that Max is inclining to a masculine polarity. It’s indicative of the play’s character and moral complexities that Isaac, instead of demanding the return of his sister, opts for masculinising Max, whereas Paige clings to the teenager’s gender ambiguity and their life together, which includes the “cultural Saturdays” she insists Isaac join — “[Our family] never loved art,” he retorts. Paige declares that Max has saved her life, which indicates how culturally and morally pivotal Max is to the play, even though Paige and Isaac are its actual plot drivers. While intelligent and sharp-witted, Max is too young, too easily bossed about to shape events, although a final gesture might suggest at least a developing empathy for defeated manhood. The question remains, will Max be constrained by Paige’s vague fantasy of abandoning the home and setting off into the greater world? The adolescent’s own dream for now goes no further than tentatively imagining joining a queer anarchist commune.

What is that greater world? There’s little reference to it, beyond Paige’s mention of impoverished, drug-addicted veterans hanging about the streets. Max is not palpably part of an LGBTQI community. Paige has a job with a non-profit that is clearly not part of her projected future. Hir’s isolated working class family is a microcosm of a society undergoing the transformations wrought by the weakening of patriarchy and the concomitant rise of feminism, queer culture and transgender identification. It’s strongly felt, hotly argued; there is violence, there is banishment and, finally, lingering uncertainty. Paige’s determination to pursue her vision is at once valid, given all she has suffered and been joyously liberated from, but it’s also obdurately limited, not least for Max.

The progression in the first act of Hir, from the riotous comedy of its opening and subsequent deliriously tense arguments to a not at all funny final scene with Isaac and Arnold alone (in which the son menacingly talks the father through a litany of the man’s brutalities), is indicative of the overall momentum across the whole play and its comedy-drama dynamic, from comic disruption to dark ponderings. Hir is not a classically redemptive, procreative comedy. Mac humours his audience, with a jolt, into being open to social transformation but also to its obstacles and the play ends without laughter. Arnold’s stroke, Max’s transgender status and Paige’s acceptance of that identity and of her own potential have wrought enormous change, its consequences only just being fully felt at Hir’s end.

Kurt Pimblett, Greg Stone, Richard Whalley, Hir, Belvoir Street Theatre, photo Brett Boardman

Director Anthea Williams and her cast honour the play’s distinctive drive from laughter into darkness with precise comic crafting and subtle characterisations that render the seriousness of daunting issues intelligible. Helen Thomson seems to blend Phyllis Diller’s deadpan bluntness and Samantha Bee’s vocal and gestural animation, reeling off Paige’s declarations and assaults with quick-fire screwball comedy verve, but, when events require it, revealing the woman’s fearsome determination, cruel as it can be, to never, in any way, return to her previous subjection.

Isaac, who, despite knowing too well his father’s sins, yearns for the status quo, is manipulative, hypocritical (he was a dishonourably discharged ‘hero’) and possibly suffering, as his mother suggests, PTSD (he was on a mortuary detail in the war, collecting body parts). Michael Whalley finely delineates Isaac’s homecoming astonishment, its convulsive physical consequences and his inherent rectitude, inflected with escalating desperation and with hints of trauma stress.

The role of Arnold limits Greg Stone to a narrower but no less impressively realised ambit in which he delineates a lost soul, uttering single words he’s heard, ordered about like a pet dog, confused about but embracing his cross-dressing and now and then revealing a surfacing undercurrent of anger and momentary knowledge of his plight. As required by the playwright, a transgender actor, Kurt Pimblett, plays Max with a vividly apt mix of teen confidence and confusion, caught between hir mother and brother and hir own impulses (sometimes to just to go to bed and masturbate), or attempting to extricate hirself from what Paige assumes are shared attitudes.

With Hir, Taylor Mac, who crafts many kinds of plays and performance art, has chosen to take on the American dysfunctional family genre which reaches from Eugene O’Neill to Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Edward Albee and Sam Shephard, but rendered it fiercely comic, to a point, and white working class. In a program note, Mac invokes Stockton, California, the town he grew up in, as the model location for Hir. Presumably, this and like towns across the country are Trump territory, but Mac doesn’t make the connection. It’s as if the radical but difficult transformation he portrays will ensue regardless of politics. But is the microcosm of change that is Paige’s dissolving family representative of a macrocosm that includes, say, Black and Hispanic Americans? That’s too big a question for this play, though doubtless one that will be raised. Instead, Mac has focused on a class where change would seem least likely incipient and shown it painfully taking shape, like a prophetic test case.