Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

As a prelude to our five-hour open conversation, RealTime in real time, as part of the Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, this edition is packed with archival delights. In a new archival feature, Writers read RealTime, contributing writers have recorded themselves reading reviews they’re fond of about shows that impressed them. The first four are by Dan Edwards, Chris Reid, Gail Priest and Jonathan W Marshall. As well, Katerina Sakkas appraises how RealTime and its writers responded to new developments in photography 2005-17. The image above, by Robyn Stacey, one of the survey’s subjects, is the result of the artist’s deployment of the ancient (500BCE) pinhole or camera obscura technique. A former RealTime staff member from 1998 to 2002, Kirsten Krauth affectingly recalls a busy creative life as editor and writer while Greg Hooper and Jonathan W Marshall look back over two decades of reviewing, frankly and incisively addressing the pleasures and challenges of the art. If you’re in Sydney on 21 October we’d love to see and hear from you at RealTime in real time. Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: Room 1526, Mercure, Sydney, Jodi, Robyn Stacey, image courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney

As a key part of our 2018 project to complete and celebrate the RealTime archive 1994-present, we’re presenting a very special event. We’d like you to be there for part or all of it. It’s free (register here).

Unfolding over 5 hours, 1-6pm on Sunday 21 October at the Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art in Sydney, RealTime in real time will be a continuous, informally-facilitated open conversation that will evolve, via chat and micro-performances, charting the remarkable transformation of the art experience over the last quarter century. How have we responded as audiences and, in RealTime the national arts magazine, as writers?

Join the RealTime Editors, writers from across Australia, artists and readers for this all-too-rare opportunity to drop in any time, stop the clock and reflect on where we’ve been.

RealTime in real time will unfold in phases of very approximately the following durations:

1.00-2.00pm: What was that: 1994-2018? Active recall, telling moments

Share reveries, shocks & revelations: technological, cross-artform, cross-cultural & hybrid, relational, intellectual, sensory and perceptual.

2.00-3.00pm: The critic tested: putting change into words

Dialoguing with artists and readers, writers reflect on adapting to the demands on their knowledge and responsiveness made by mutating artforms and emergent issues.

3.00-4.00pm: RealTime and the place of the space

Prompted by visiting the Performance Space archive, this exchange gauges the critical role of contemporary art centres across Australia as homes for and agents of change.

4.00-4.20pm: Eat/drink/talk

4.20-6.00pm: The big picture 1994-2018, the real story?

In the face of art done over by politics, diminished reviewing and archival challenges, how deep, enduring and sustainable are the innovations and cross-cultural engagements of 1994-2018? What to regret, what to celebrate? And more eating, drinking and talking.

HOSTS:

Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch, Caroline Wake, Erin Brannigan, Gail Priest & Katerina Sakkas

WRITERS:

SA: Ben Brooker, Chris Reid; WA: Darren Jorgensen, Jonathan W Marshall;

TAS: Andrew Harper, Lucy Hawthorne, Briony Kidd; QLD: Kathryn Kelly, Greg Hooper; Rebecca Youdell, Russell Milledge [Cairns]; VIC: Jana Perkovic, Andrew Fuhrmann, Philipa Rothfield, Rachel Fensham, David Williams, Richard Murphet; ACT: Zsuzsanna Soboslay, Jane Goodall; NSW: Vicki Van Hout, Julie-Anne Long, Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch, Martin del Amo, Sarah Miller, Matthew Lorenzon [ex-VIC], Gail Priest, Tony Osborne, Cleo Mees, Fiona McGregor, Jonathan Bollen, Bryoni Trezise, Nikki Heywood, Caroline Wake, Katerina Sakkas, Felicity Clark, Djon Mundine, Karen Pearlman

PERFORMERS:

Vicki Van Hout, Julie-Anne Long, Andrew Harper, Martin del Amo, Emma Saunders, Nikki Heywood & Tony Osborne, Cat Jones and more

FREE

Register here

–

RealTime in real time,

Performance Space, Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, Carriageworks, 245 Wilson Street, Eveleigh, Sydney,

1-6pm, Sunday 21 October

Top image credit: Keith Gallasch, Virginia Baxter, masks Beatrice Chew, photo Su-Ann Ng, art direction Graeme Smith

As part of our celebration of the RealTime Archive, we thought you might like to hear the actual voices of our contributors, so we’ve invited them to record readings of reviews of favourite works.

Given the tyranny of distance and the ubiquity of recording technology the writers have made their own recordings and sent them through — a little like calling in from the front — offering extra real-ness to the RealTime experience.

You’ll find these and recordings to come in Writers read RealTime in the RealTime Audio section of our online archive.

Our thanks to Gail Priest for initiating and managing this project and providing the title music.

Dan Edwards: Australian Western: Fear on the frontier

Dan’s eloquent reading captures the vividness and thematic cogency of his review of director John Hillcoat and writer Nick Cave’s feature film The Proposition (2005), a seeming Western that tests white Australian myths.

RealTime issue #70 Dec-Jan 2005

Jonathan Marshall: Deep inside the box

Embracing the work’s disturbing structure, Jonathan applauds writer and co-director Richard Murphet’s The Inhabited Man as a “dense, beautiful yet traumatising dramaturgical essay” about the psychological damage imposed by war.

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008

Gail Priest: The improvising organism

In her first review for RealTime, in 2002, Gail alertly captures the dynamic intricacies, the sounds and sense of immediacy that is a Machine for Making Sense performance.

RealTime 48 April-May 2002

Chris Reid: Creek learning

Chris appreciatively describes an intimate live art walking event that takes him along a suburban Adelaide creek, revealing subtly installed artworks, distinctive flora and recollections of Aboriginal heritage.

RealTime online, 20 June 2017

–

Icon image credits, top to bottom:

- Guy Pearce, The Proposition

- Foreground: Merfyn Owen, The Inhabited Man

- Jim Denley, Stevie Wishart, Amanda Stewart, Rik Rue, Machine for Making Sense, 2002

- Embed, 2017, site-specific ephemeral work, Laura Wills, Creek Lore, commissioned by Open Space Community Arts (OSCA), photo Juha Vanhakartano – Valo Productions

I started working at RealTime in my twenties from 1998 to 2002, fresh out of university and a background steeped in cultural studies, film production and poststructural theory. I was a closet writer, drawn to arts and publishing, but uncertain in those first steps you take into a possible career. I was also new to Sydney, having abandoned Melbourne then Queensland where the recession meant no jobs for graduates in media or communications. When it came to the arts, I was more mainstream than Keith and Virginia might have imagined, but with a sense of the obscure and abstract ignited by a major in cinema theory at RMIT with Adrian Miles and Mike Walsh, who went on to write regularly for RealTime.

In the interview for the assistant editor position, they asked me if I liked opera. I said I liked everything. This was pretty much true and hasn’t changed: I’m open to the elements. To apply for the job, they asked for examples of my writing. I sent miserable poetry, a couple of early short story drafts I’d never shown to anyone else and an essay about Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil. Or perhaps it was David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I remember Keith’s response clearly: “You were chosen on the potential of your fiction.” It struck a chord and inspired me to action in terms of my essay skills. Keith and Virginia commissioned me to write 1500 words per edition for four years. One hundred articles later, it was the best education in the Australian arts scene, arts writing and editing I could have imagined.

I put my hand up for any free ticket. I saw dance, performance art, digital media, sound installations, documentary festivals. I was often afraid and bewildered as an audience member — the only person in the room who didn’t get it. I initially preferred the boundaries of stage and performer (gasp!). But I learnt to love crossing this line and many others. A highlight was attending the 2000 Adelaide Festival as a roving arts commentator, responding daily and on the go to produce mini-editions; I loved the thrill and risk and the intense immersion — and how the writing seemed to stand up to the task. It was in the process of subediting each edition of RealTime that I came to understand how to get it. It was a massive job putting an issue together: intellectually rigorous, stimulating, finding depth in the new.

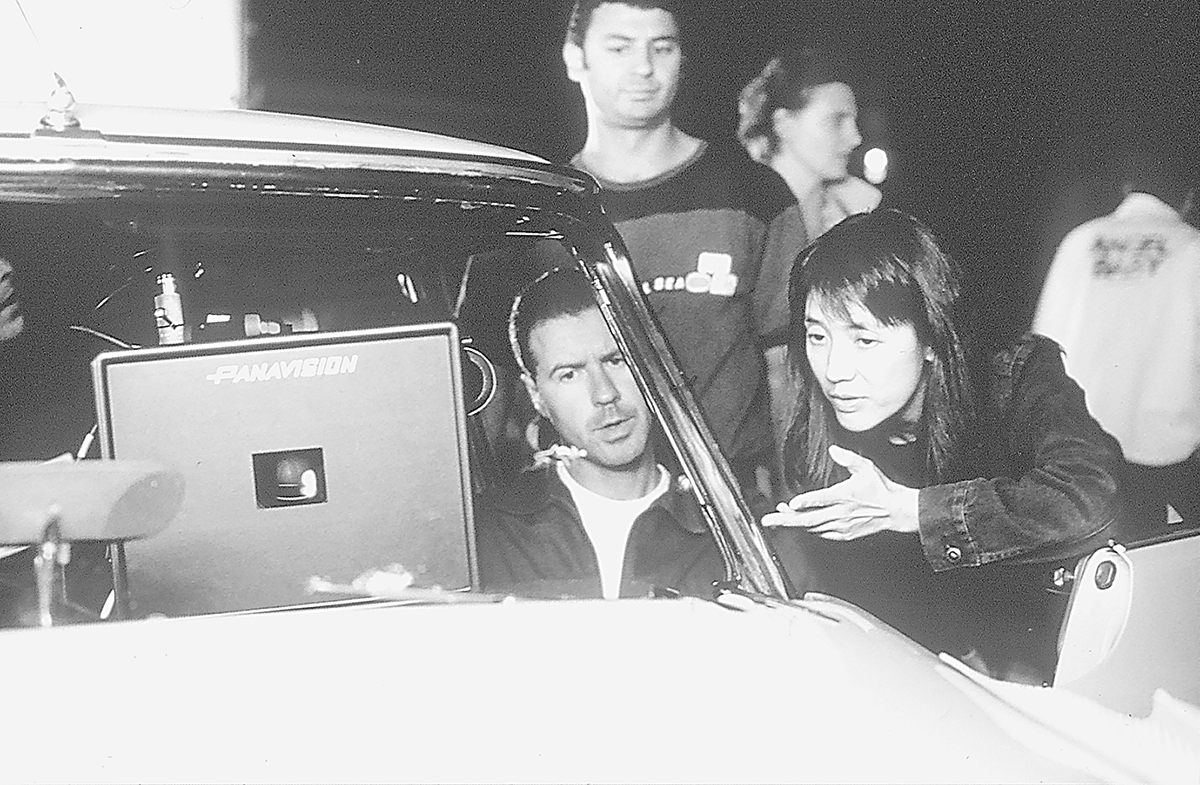

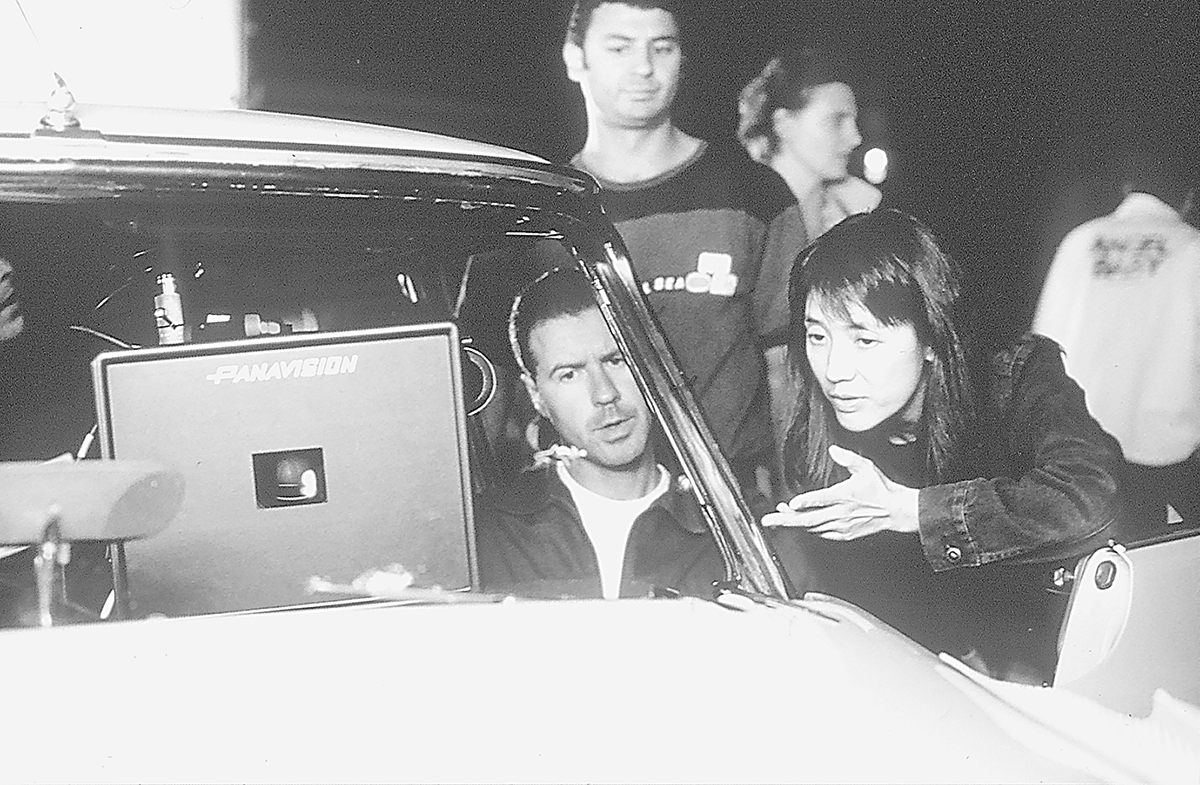

Clara Law directs The Goddess of 1967, 2001

A number of artists stay with me years later: Lucy Guerin, Les Ballets C de la B, Justine Cooper, Kate Champion, Ross Gibson, Legs on the Wall, Martine Corompt, Ivan Sen, Not Yet It’s Difficult, Cate Shortland, Clara Law. And a number of writers too, those who I always put on the bottom of the pile to be read, a reward at the end of the day: Phil Brophy, Erin Brannigan, Simon Enticknap, Melinda Rackham, Mike Walsh, Mireille Juchau, Bec Dean, Daniel Palmer, Josephine Wilson and Adrian Miles (a sad farewell, Adrian). But I can’t actually guarantee that I saw the above artists’ work IRL. Sometimes the writing by RealTime writers was so evocative I now remember it as if I was really there.

Looking back on my fledgling articles, I see all the mistakes of a beginning writer: the need to impress, the need to obscure, the need to show off style for no apparent reason, the need to endlessly repeat words to go on the rhythmic road with Kerouac and Burroughs, the redundancies (that was a new word I heard often, ouch!) and the tendency to use the form of wit as cruelty — something I’d never do now. Much of it was obfuscation but as the articles progressed, I began to experiment and found I was in the right place to test things out. I liked how the real time idea infused the writing, the sense of experiencing the show as keen as the show itself. It was an exciting discovery, fictocriticism, and one I have enjoyed since. I recently followed Laurie Anderson around HOTA (Home of the Arts) on the Gold Coast for a week and as soon as I arrived I felt this kind of RealTime-comfort-zone, the space of the lyrical essay laid out before me.

A couple of years into my life at RealTime, I became Editor of OnScreen, the film and digital media section. Film remained my passion. At the media screenings — sitting next to David Stratton towards the centre with his umbrella perched on a seat or Margaret Pomeranz laughing in the front row — the reviewers were given champagne and snacks in penthouse suites. After a good film all the reviewers were silent in the lift down. I couldn’t really believe I got paid for such pleasure. But with all the genre-bending and boundary-pushing going on around me, I found it hard to return to traditional forms. When Keith asked me to write editorials for OnScreen, I’d spend months trying to work out how to subvert this idea: an editoral about why no-one reads editorials?

There was a great sense of possibility in film culture at the time, especially in shorts, documentaries and Indigenous filmmaking or films about Indigenous stories. Ivan Sen, Rachel Perkins, Beck Cole, Warwick Thornton, Catriona McKenzie and Darlene Johnson were starting to make evocative films. Highlights for me were Ivan Sen and Cate Shortland experimenting with form and narrative style in shorts (Sen’s Tears, Dust and Wind; Shortland’s Pentuphouse, Flower Girl), before going on to make features, while in documentary Dennis O’Rourke’s Cunnamulla was bringing similar themes to the surface in his exploration of teen girls in a small country town and their (lack of) options. I received only two pieces of fanmail working at RealTime and both were about this article: Mark Mordue wrote to encourage me re style; O’Rourke wrote to thank me for getting it:

“The annual lizard race features on the Country Link brochure. ‘The most boring entertainment I’ve ever witnessed,’ according to Neredah, who’s seen a lot; she observes for a living. Local contestants are rounded up and placed in a large circle. First to the line wins. No worries, this’ll be a quickie, but what happens? Overcome by collective inertia, they will not, cannot, move. A man stomps. Nothing. Is it lethargy, fear or an attempt to fit in that’s holding them back? Cara and Kellie-Anne know the answers but they’re in a bus heading to the big smoke…”

Shelley Jackson, Patchwork Girl

My years at RealTime, both in day to day work and content, were mostly about the slow dawn of the digital, the melding of text and screen. It felt like everything was new but looking back it was ponderous. I did the RealTime website using only HTML coding which took days and days, I didn’t have a mobile, there was no social media, and all the images in the paper — “must be from the performance, not publicity shots“ — were beautiful black and white photographs, sent by publicists or artists between flat bits of cardboard that I scanned and posted back. I thought CD-Roms were going to revolutionise storytelling. I became interested in the intersections formerly known as hypertext and wrote a regular column called Write Sites, as far as I know the only one in Australia devoted to this genre. I interviewed Eva Gold about the world-first inclusion of hypertext Patchwork Girl in high school curriculum.

“Patchwork Girl looks at the act of writing as much as text itself, ‘tiny black letters blurred into stitches,’ as a creation process not full of Mastery; this is a woman making a monster, this is Mary/Shelley. The metaphors of quilting and patchwork have been consistently used for hypertext writing (eg TrAce’s Noon Quilt project), sewing together nodes, acknowledging the process as much as the outcome, its made-ness.”

Many digital media artists covered, like Mez and Jason Nelson, went on to become internationally renowned practitioners. But it wasn’t a genre that captured much attention in Australia. Looking back, there was a stiltedness to the text, the visuals and process, the merging of the fields, as compared with video games, covered by the brilliant Alex Hutchinson:

“An important thing to remember is that video games were born on, and exist only on, computers. Unlike pure text, they are the rightful heirs of the digital age, not its bastard children. The ‘links’ between text fragments become the doorways between rooms rendered in 3D. The text ceases to describe or refer to the image, and begins interacting with it, fleshing it out, giving it greater depth. Your average game player becomes blind to the fact that s/he is making choices between fragments, and their reinterpretation of the game becomes fluid. S/he ceases to be an external force acting on the text and becomes another facet of it.”

In terms of my own writing experiments it was hard to know when to stop. To their credit (arguable) and my surprise, Virginia and Keith often went with it. One of my strangest memories is of writing about digital porn (gasp!) under the avatar Ivana Caprice with her husband Art, new to the internet. I have no idea why. I thought this was the most hilarious thing I’d ever written until I watched the faces of the proofreaders when they came to this article. They didn’t smile. Once. They just didn’t get it.

“Art tries to download Jessica’s shoot right to our computer. Here’s Amy, ‘wild crazy…watch her lean back and piss into a glass bowl.’ Look at the quality of that scan, Art cries, zooming into a pierced nipple. They use digital cameras, the site says proudly, giving a quick plug to the Sony VX 1000. See pissing, fisting, bottle and veggie insertions, and a speculum … I have to certify that ‘anal sex, urination, vegetable and bottle penetration and fisting, do not violate the community standards of [my] street, village, city, town, country, state, province or country.’ I am nervous about this …Aaaah, ooooooooh, 2 girls are engaged in a lip pulling contest and then there’s the carrots. Eggplants. Zucchinis. Squash. Art reckons this site’s so hot he’s going to cook a stir fry tonight.”

With a small team (Keith, Virginia, Gail Priest and I), RealTime felt like family for many years. Passionate, hard-working and unconventional, Keith and Virginia had a strong sense of vision and support for innovative artists and writers. And it was a publication I leant on heavily even as I stopped working there. If I had an unusual idea about a new TV show or a regional artist/event to cover they were always keen. Sometimes, years later, when I’d take the train in from Castlemaine and pick up the paper at a café in Melbourne, I’d think ‘who are all these artists?’ Many amazing practitioners flying under the radar except for Realtime. It now feels like there’s a large gaping hole.

But one thing Keith and Virginia were always good at was archiving. I spent a lot of time setting up FileMaker databases and entering data. Being able to see all this content online now, at least in terms of my earlier writing, has been a wistful, revealing and sometimes excruciating experience. But more wonderful has been the chance to revisit the RealTime writers and artists we nurtured along the way, many still thankfully going strong 25 years later.

–

Kirsten Krauth is a writer and editor based in Castlemaine. Her first novel just_a_girl was published in 2013 and her second in progress is based around the twilight worlds of the early 80s Melbourne music scene. She is editor of Newswrite for Writing NSW and her writing has appeared in The Saturday Paper, ABC Arts, Good Weekend, The Australian, SMH/Age, Island, Australian Author and Empire.

Top image credit: Cunnamulla

Fiona McGregor is a Sydney writer and performance artist. She has published five books, including Strange Museums, a travel memoir of a performance art tour through Poland. Her most recent novel Indelible Ink (2010) won Age Book of the Year. McGregor writes essays, articles and reviews for many publications including RealTime, Overland, The Monthly, The Saturday Paper, Runway and Running Dog. Her photo essay A Novel Idea, an exploration of the process of novel writing under the rubric of endurance performance, will be published by Giramondo in March 2019.McGregor’s performance has been shown internationally. From 1998 to 2005, she worked with collaborative duo senVoodoo, then went solo. Her intervention Dead Art saw her carried from the Museum of Contemporary Art by NSW Police. You Have the Body, a meditation on unlawful detention, toured Australia 2008-09 and was voted Show of the Year by theatre critic James Waites. In 2011 McGregor created the multidisciplinary Water Series at Artspace, a collection of durational and endurance performances with trace installations, as well as video.

Since the 90s, Fiona has been involved in Sydney’s queer alternative performance and party culture. She co-produces annual fundraiser dance party UNDEAD for grassroots organisation Unharm, which campaigns for drug law reform and de-stigmatisation.

She is currently working on a collection of non-fiction, a trilogy of novels based on the life of Iris Webber, a busker and petty thief, set in the criminal milieu of 1930s inner Sydney, and a large collaborative performance project.

Website: www.fionamcgregor.com

Exposé

I’ve come a full circle with criticism. As a young writer I believed in the pejorative, Those that can’t do it, talk about it. Then, when RealTime commissioned an article in 1994 on Dyke Performers, I began to see things differently. It was a culture that I lived and breathed, and I saw the value of interacting with it as a writer. I could bring the work to a wider audience, observe and analyse it in a way the artists couldn’t due to proximity, and extend myself as a writer. Once I began to practise as a performance artist myself the exchange was enhanced but it was another 10 years before I could write about my own work. Over the decades I’ve become an avid reader of critical writing and I now think it’s invaluable. As an artist I’m grateful when someone engages critically with my work. It’s tricky in a small beleaguered community to strike a balance between being supportive and being honest. I can lie awake worrying about reviews that take days to write and pay $120! The best critical writing doesn’t necessarily come from the best art. It’s serendipitous. The critic needs to pay attention, dig deep, hang onto their humour and most of all be brave, be honest. Dare to say the stuff nobody else does. Don’t deny your personal take but also don’t get blinded by it. Not that dissimilar to tenets for the artist. I’ve developed a strong sense of cultural custodianship, which fires both my criticism and my art.

Fiona’s first RealTime article appeared in RT 2, p4, 1994

Pap Smears and Whipped Cream: Dyke Performance in the 90s

Recent articles for realtime

Climate change, culture threat: Blacktown Arts Centre’s Disaffected

Ice, art & urgency: Latai Taumoepeau, Repatriate I & II

Asia-Australia: art, conscience, action: 4a Centre For Contemporary Asian Art, 48Hr Incident

Enduringly queer: Day for Night, Performance Space

How does your live art grow?: Liveworks, Performance Space

Photography has always been integral to RealTime, something instantly apparent in the considered and arresting series of cover images that signal the magazine’s commitment to boundary-pushing art. From RealTime’s inception in the mid-1990s, when photography was coming to dominate contemporary visual art, the editors closely followed developments, particularly in an Australian context, in this medium they saw being used in compelling, exploratory ways.

As I researched my recent overview of RealTime’s visual arts coverage during its first decade (1994-2004), I witnessed a medium in flux (particularly with the advent of digital technology) that lent itself to a multitude of approaches and discourses as it grew beyond the confines of conventional categorisation: documentary and ‘fine art’ photography, advertising imagery, snapshots. At the end of RealTime’s first decade, photography was clearly established as a contemporary artform, one uniquely placed, given its reputation for veracity, to be used by artists as a means of manipulating, subverting, interrogating or distorting ‘reality.’

Laying a solid, scholarly foundation for RealTime’s photography coverage post-2000 was novelist and assistant editor (c.2001-2004) Mireille Juchau, whose affinity with the medium is striking across a range of photography-related articles, including book reviews, interviews and responses to exhibitions both large-scale and intimate. In her review of two major photography exhibitions, at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art and the Art Gallery of NSW, she takes on an eclectic array of artworks via a richly visual analysis synthesising the medium’s historical underpinnings and the manifold discourses and meanings to which it lends itself. “Photographs are not presented in either exhibit as a means for capturing ‘the real,’ but as a springboard for contemplating the internal life of dreams, the imagination and subjectivity within specific historical, cultural and political contexts.”

Her observations bring out photography’s enigmatic, paradoxical character, its propensity to render that which it captures, elusive. Looking at Polixeni Papapetrou’s series Phantomwise at Stills Gallery, Juchau finds herself scanning the works for a hint of the four-year-old child, Papapetrou’s daughter Olympia, behind the masked, archetypal guise she adopts in each image.

“Why do we search these deathly pictures for signs of life? Perhaps because as Papapetrou’s title suggests, the frozen charades in each photo seem less like child’s play than a phantasmagoria, less like performance than stasis: a series of lifeless caricatures.”

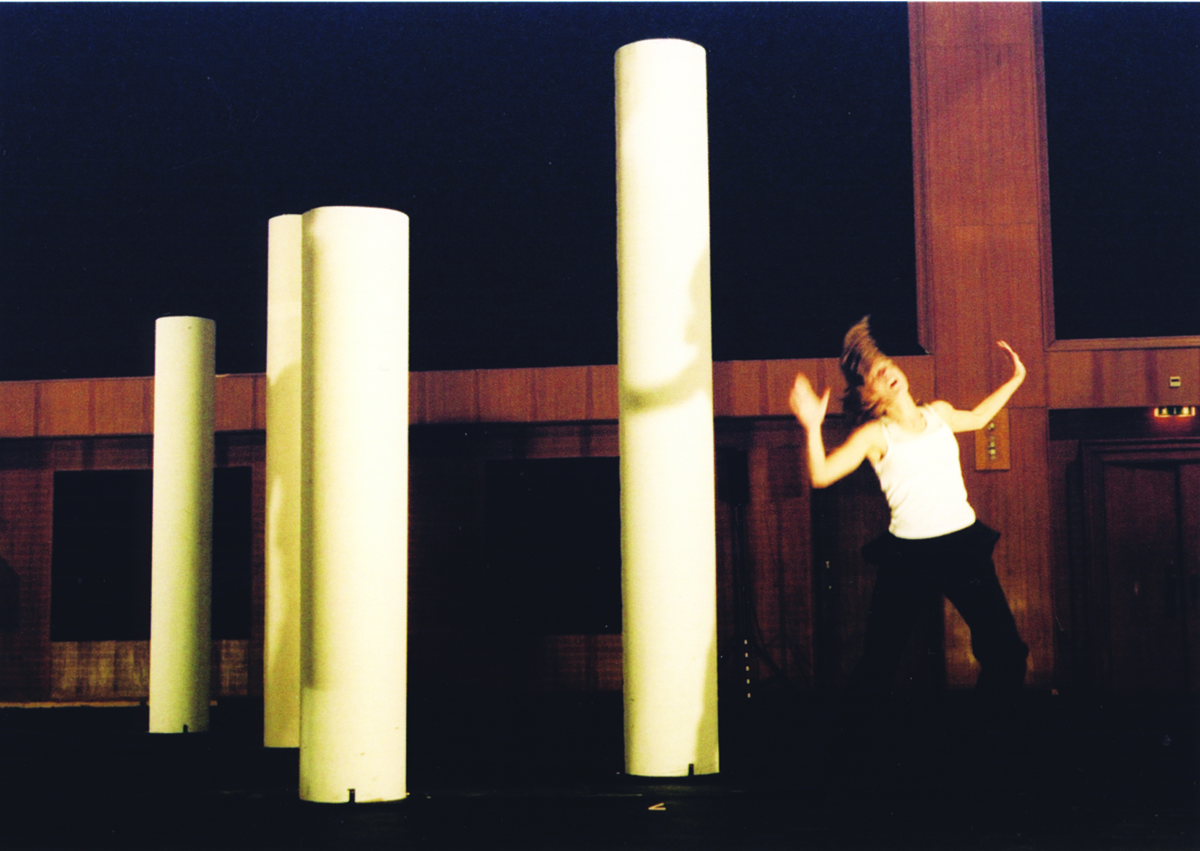

Hyper No. 04, Denis Darzacq, Perth Centre for Photography

Playing with documentary

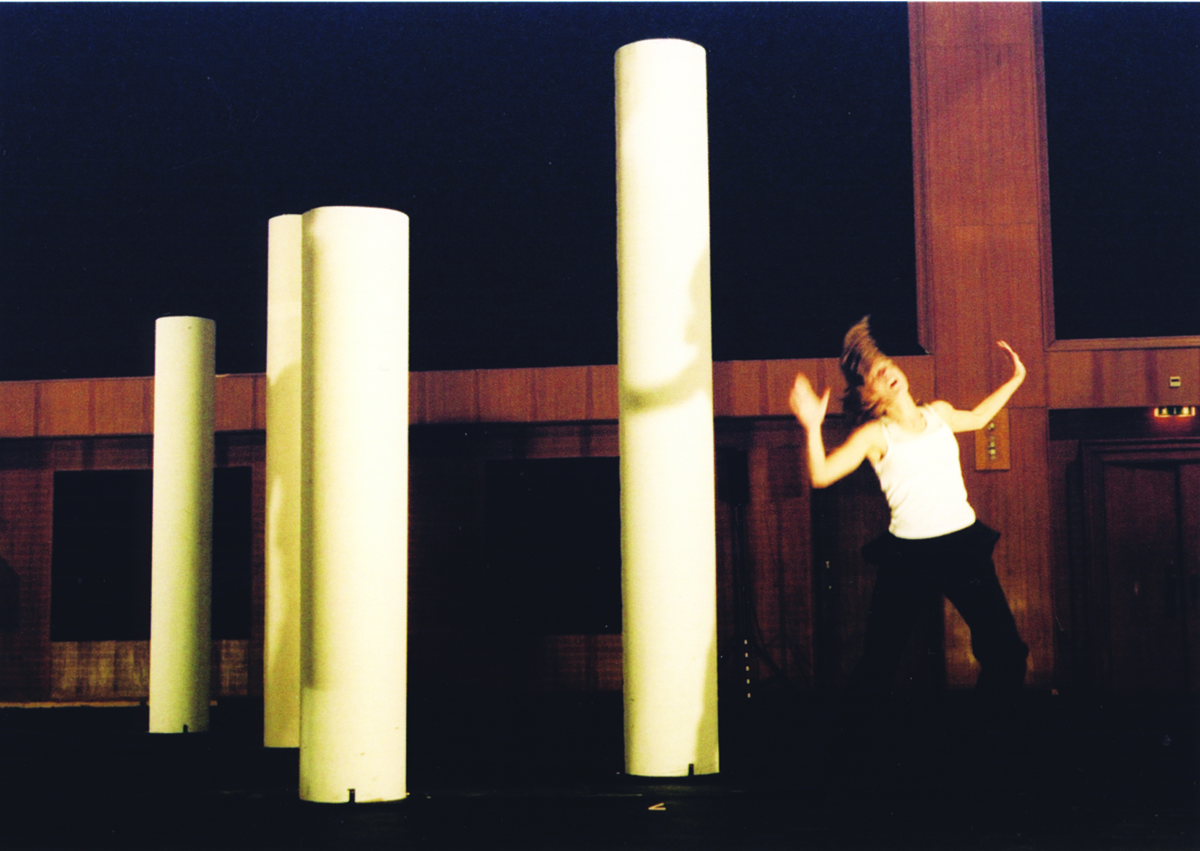

Darren Jorgensen’s 2008 and 2010 reports on Fremantle’s eclectic biennial photography festival, Fotofreo, are superb contextual overviews, explaining photography’s documentary roots, and its current ubiquity, before presenting a selection of festival artists self-aware enough to rupture our assumptions of the medium.

Steering away from an illusionistic presentation of reality, Jorgensen finds artists in the 2008 festival who draw attention to substances and surfaces, like Perth-based Alex Bradley, “merging the televisual and biological” by swamping Hitchcock film images and TV visuals in close-ups of blood and sperm; or those who “play with our naturalistic expectations of the medium,” like France’s Denis Darzacq with his gravity-defying dancers suspended above supermarket aisles. Through photographing the passports and possessions of victims of the Rwandan massacres, London-based Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin “in an exhibition that defamiliarises and makes radical the naturalising function of photography…show how the evidence of violence is not always violence itself.”

The Healing Garden, Wyabalenna,Flinders Island, Tasmania, from the series Portrait of a distant land (2005)

In 2010, Jorgensen writes of “category confusion,” observing slippage between conceptual and documentary forms in Tasmanian photographer Ricky Maynard’s diptychs featuring Tasmanian Aboriginal portraits and landscapes, unremarkable on the surface but unsettled by captions detailing historic atrocity. “The haunting of Tasmania appears to bleed through the image, as Maynard brings his documentary mode of photography to life with conceptual information.”

The Three Sisters, Katoomba, 1898, Ernest B Docker, stereograph, Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, The Photograph & Australia, Art Gallery of NSW, 2015

Histories

“Photographs have become a way of seeing ourselves. They’ve become a way of being ourselves. From the beginning, the photograph was taken up into real life, capturing imaginations.” Viewing a major historical exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW in 2015, The Photograph and Australia, writer Robyn Ferrell is presented with a singularly neat example of symbiosis between photography and history, given colonial Australia and photography’s shared time frame. “The two have grown up together, so that now to display a history of photography in Australia is to display a history of Australia, and likewise a history of the photograph.”

Ferrell considers photography’s inherent characteristics and the way these influence our conception of reality. “It reproduces reality in a specific way — it renders it two-dimensional, it confines it to a frame, it edits out all senses but the visual. These critical elements shape our vision of what there is.” Taking this into account, can all photographic histories be considered in a sense alternative or parallel to the events they document; altered and influenced both by the formal qualities of the medium and the perspective of the one behind the lens?

Poles Apart (2009), r e a, Breenspace

RealTime explored the work of various Australian conceptual artists who exploit photography’s association with the recording of history to present alternate histories that illuminate what has been omitted from the official record. In her photographic series Poles Apart at Breenspace (2009), Indigenous media artist r e a flees in 19th century garb through a charred bush landscape, her narrative scenes deliberately collapsing the pioneer paintings of the Heidelberg School – to whom “Indigenous people were invisible” – into the artist’s familial history of enforced separation and displacement. Virginia Baxter writes, “The artist takes colonial and art history, personal memory, painful lived experience and distils them into a powerful exhibition, which expresses the frustration and anxiety of living in a country that refuses to truly acknowledge its Indigenous history and heritage.”

Pilar Mata Dupont, Tarryn Gill, Blood Sport (2010) detail, photo courtesy the artists and Goddard de Fiddes Gallery, Perth, photo Kim Tran

Multimedia art duo Tarryn Gill and Pilar Mata Dupont also take a performative role, in their signature camp set pieces parodying the artifice of nationalistic propaganda. A decade into the artists’ successful career trajectory, Laetitia Wilson vividly analyses their oeuvre through the lens of a large 2011 survey show at PICA entitled Stadium, where the artists pose as Riefenstahl-like athletes, surf lifesaver-pinups and the 1968 heads of state of their respective birth countries, among other personae. “The seductive glamour, burlesque, kitsch-Australiana and Hollywood styling is adopted with a wry stare derived from a deeper critique of issues anchored in nationalism, militarism and patriotism…Gill and Mata Dupont demonstrate just how easily a golden propaganda machine can mask sinister realities. They dance through the games of the art world distracting and seducing onlookers with their rich and glittery aesthetic.”

Fever Dash, Adelaide (2014), Trent Parke, Black Rose exhibition, image courtesy the artist and Art Gallery of SA

Waking dream

Photography’s believable façade can also be manipulated to conjure otherworldliness, as experienced by Virginia Baxter and Chris Reid in the epic, autobiographical installations of Australian photo-artist Trent Parke. Parke is a master of chiaroscuro, the interplay of light and dark at the heart of photography. His imagery explores photography as a kind of shadow form, both literal and figurative. “In the series of large, unframed photographs that follows, Parke works the film to its limits, employing his trademark wide-angle slabs of black intersected by myriad patterns of light to powerfully reveal a shadowland of violence and unease,” Baxter writes in her 2005 review of Parke’s road-trip exhibition Minutes to Midnight.

And of a later (2015) installation, Black Rose, Chris Reid writes, “The exhibition is set out as a personal retrospective whose elements are stitched into a narrative, a journey of memory, imagination and dreams like a story told in cryptic vignettes.” Parke, the only Australian member of the prestigious Magnum Photos collective whose founders included Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, also calls attention to the technical processes of analogue photography; Baxter describes images from Minutes to Midnight in which Parke washes rolls of film in a grimy shower block. In Black Rose, Reid notes, “the last room of the exhibition contains hundreds of rolls of developed film, hung like a curtain against bright light for our inspection, representing not only the vastness of his oeuvre but Parke’s commitment to continuous observation.”

Twins, Pat Brassington, 2001, series Gentle, Fotofreo, image courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery, Sydney

The surreal manipulations of another prominent Australian contemporary photographer, Pat Brassington, also transport RealTime reviewers across the threshold of consciousness, to an uncanny world of warped domesticity and discombobulated femininity, “the haunting material of dreams,” as Darren Jorgensen puts it in his RT 97 Fotofreo overview. “Her renderings of torsos, tongues and limbs in pink, brown and orange exposures have the mark of a suburban imagination gone strange.” Responding to Brassington’s 2005 exhibition at Stills Gallery, Virginia Baxter is characteristically evocative: “Entering her latest exhibition, You’re so Vein, feels like falling into some powerful infantile fantasy. Here are partial views of the body, sensuous and disturbing maternal images from the subconscious rendered in soft focus, like dreams.”

People who look dead but (probably) aren’t, Patrick Pound installation, image courtesy the artist and Stills Gallery Sydney, 2014

Vernacular

In more than one of RealTime’s photography reviews, the ubiquity of the medium is remarked upon as a complicating factor for photography-as-art. Across three Sydney exhibitions in 2014, Sandy Edwards examines a new trend towards the re-evaluation and embrace of ‘vernacular’ photography – “commonly interpreted as photography of everyday life, frequently produced by amateur photographers and often described as snapshots” — within visual arts discourse, to liberating effect.

“To collapse the snapshot aesthetic with the broad intentions of documentary photography performs a radical shift in perception benefiting both forms. It allows us to re-evaluate the rigid conventions of fine art photography, which needed to be in place to get photography seen as an artform in the first place.”

Increasingly used by postmodern artists like Patrick Pound, and Thomas Sauvin in his magnificent installation of more than half a million discarded photographic negatives, Beijing Silvermine, mounted at 4A Centre for Contemporary Art, the personal snapshot is naturally elegiac, possessing the death-in-life quality Roland Barthes identified in Camera Lucida. As Edwards expresses it: “Somehow this powerful metaphor for the brevity of life sums up the significance of photography in general and positions the vernacular photograph right at the heart of it.”

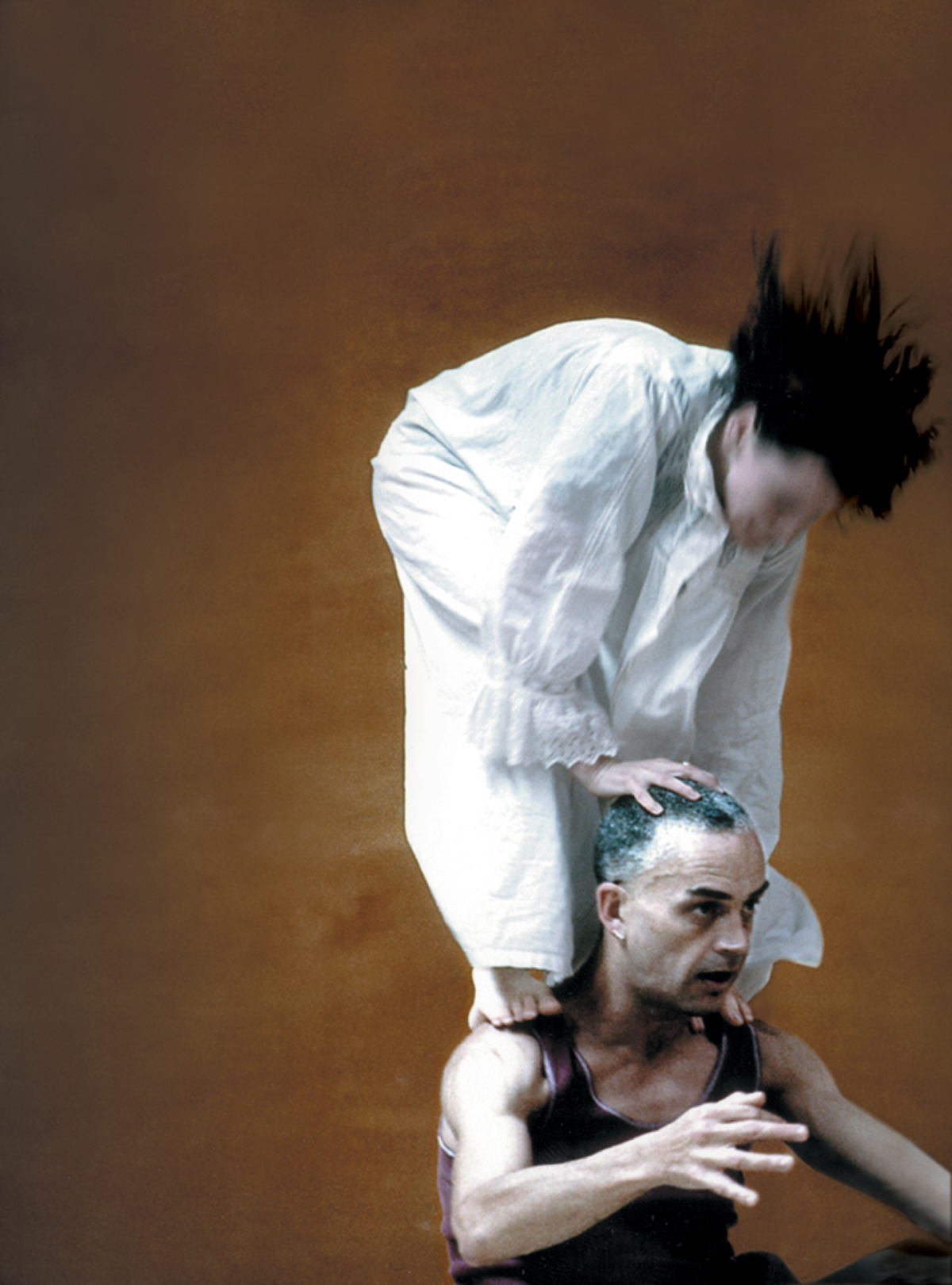

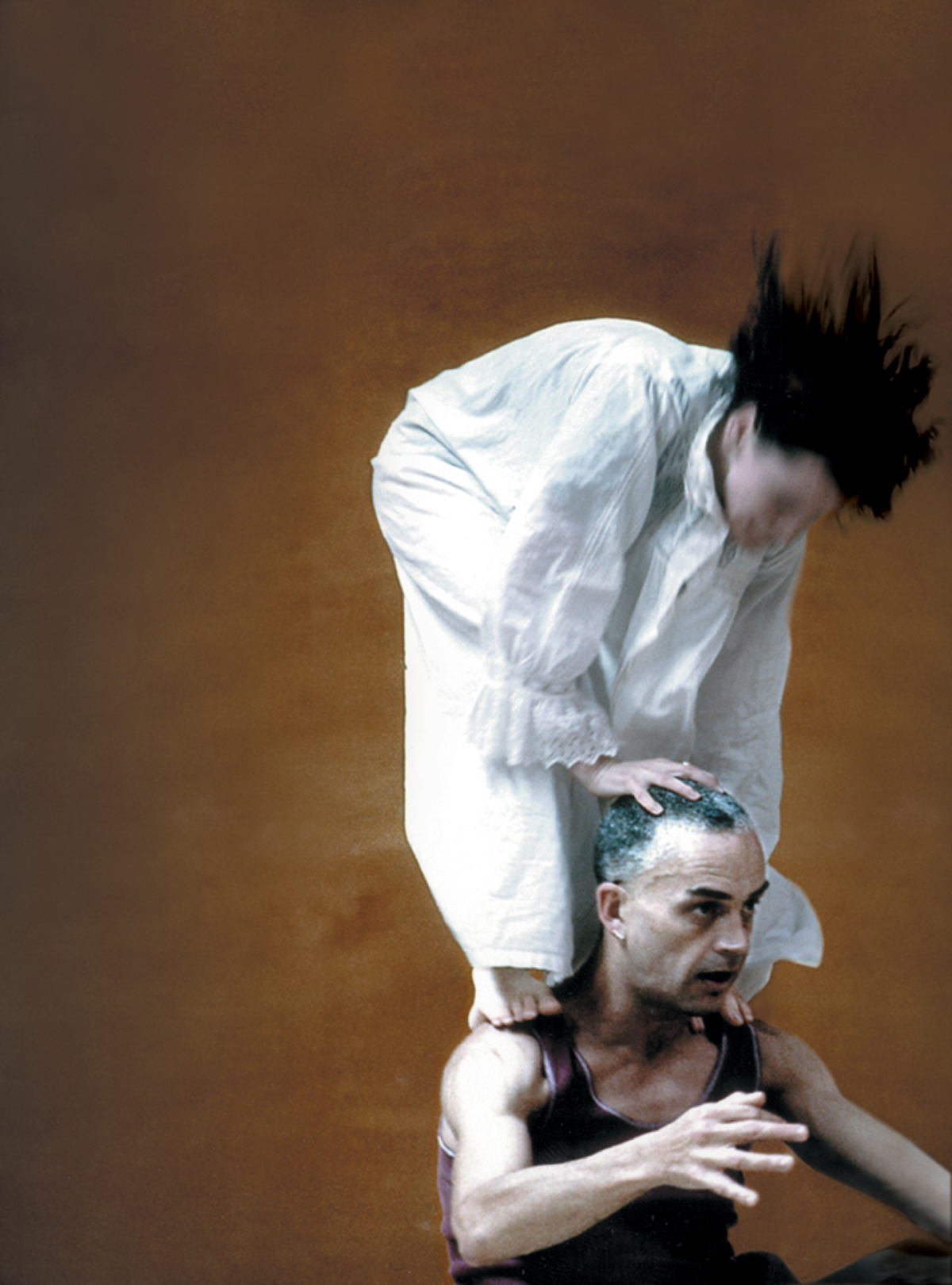

Kate Champion, About Face (2001), Heidrun Löhr, Parallax, The Performance Paradigm in Photography Australian Centre for Photography, 2012, image courtesy the artist

Collaboration and performativity

Capable of creating moments of exquisite stillness, as in the images of English photographer Craigie Horsefield, whose subjects are rendered quintessential, monumental, timeless (see Mireille Juchau’s review, Conversation in Slow Time, RT 79), photography conversely lends itself to dynamism, in truly collaborative projects that exist both as object and performance, stillness and motion. This characterises the practice of Heidrun Löhr, whose documentation of performances runs vitally through RealTime’s existence. In her review of Löhr’s 2012 solo exhibition, Parallax, at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sandy Edwards highlights Löhr’s talent for evoking movement through a still form, pushing the limitations of the medium in suggestive ways, experimenting with blur, mastering sequential photography.

As well as documenting staged performances, Löhr works in highly collaborative ways with performers who improvise for her camera. Most exciting for Edwards is an animated work involving 2,500 still images:

“In an improvisation staged solely for Löhr’s camera, performer Nikki Heywood enacted a work about her mother’s bouts of dizziness and falling in the now empty Edgecliffe apartment where she had lived. Captured in five days by Löhr’s camera and edited into a stunning animation, we see Heywood embodying her mother’s vulnerability. The pacing of the editing speeds up and slows down to emphasise the emotionality of the relationship.”

True collaborations too are Italian photographer Manuel Vason’s performative portraits of live artists, captured in five shots only, described in a vivid review by Tim Atack: “…these are performances for the camera, unique and brief—as brief as the snap of a shutter.”

Shan, from the series Primal Crown, 2012, Shan Turner-Carroll, HATCHED National Graduate Show, 2013, PICA, image courtesy the artist

Identity and self-portraits

The cover of RealTime’s 2013 education issue (theme: Utopias and Horrors) displayed an image from that year’s HATCHED National Graduate Show: Shan Turner-Carroll’s Shan, from the series Primal Crown. Cast into relief against a black background like one of Arcimboldo’s cornucopian portraits, the artist’s elaborate headdress, face paint and introspective stance carry the weighty suggestion of a personal mythology. “In a new take on the portrait, Turner-Carroll displayed a series of ‘makeshift crowns for his family made from found objects that hold personal significance —relics embedded with present memories and future thoughts’ (catalogue).”

There’s a resonance here with the photographic self-portraits of Indigenous multimedia artist Christian Thompson, whose work appears regularly in RealTime. In a comprehensive review of Thompson’s 2017 survey exhibition Ritual Intimacy at Monash University Museum of Art, Andrew Fuhrmann responds to Australian Graffiti, a series of head-and-shoulders self-portraits in which the artist is garlanded in Australian flora, face partially obscured. “In the present context, however, the images seem also to participate in a rite of personal mythmaking. The floral ornaments start to look like sacred headdresses or the paraphernalia of a private cult; the fierce eyes staring out from the shadows, behind the bright flowers, are like those of a zealous new initiate.”

Para-Selves #4, Gwan-Tung Dorothy Lau, HATCHED National Graduate Show 2017, PICA, digitally manipulated photograph courtesy the artist

Citing Thompson as an influence, young multimedia artist Gwan Tung Dorothy Lau is interviewed in the 2017 education feature about her arresting series of digitally manipulated self-portraits, Para-Selves, in which the artist is kept in check by various doppelgangers. Born and raised in Hong Kong and possessing dual Australian citizenship, her work is a metaphor for the at times oppressive nature of negotiating cross-cultural identity. “I examine the way my actions oscillate between conforming to and excessively defying generalised portrayals of East-Asian culture. By figuratively depicting that observation, I attempt to evaluate and critique the influences of Western social expectations on cultural minorities.”

Room 1306, Mercure Potts Point, Jodi (2013); Robyn Stacey, Guest Relations

In-between spaces: photograph as environment

Some artists confound our expectations of photography, using it to create immersive installations that transform the medium from 2D ‘window’ onto an environment into an environment itself, simultaneously material and illusory. In a substantial 2012 interview, Keith Gallasch delves into the complex sculptural/photographic practice of German artist Thomas Demand, who reproduces “the everyday (houses, garages, bathrooms, kitchen implements, lawns, buildings, a pipe organ even) as life-size sculptures in paper and card, eerily stripped of surplus detail and commercial branding, getting down to some kind of worrying essence.” Demand achieves this through a process of turning 2D photographs into 3D sculpture, which he in turn photographs. He describes photography, the raw stuff of his work, as “a great commonplace…a global agreement on how to recognise the world in a representation.”

The interview is conducted in the lead-up to Demand’s installation The Dailies, at the idiosyncratic Commercial Travellers’ Association hotel in Martin Place, Sydney. Graeme Smith’s subsequent review in RT 109 unrolls in a series of elegant vignettes paralleling his experience of the exhibition. Smith is struck by the impression Demand creates, along with his collaborators, novelist Louis Begley and designer Miuccia Prada, of the sort of ‘non-places’ typified by hotel rooms, with their in-between quality; the sense of combined presence and absence that pervades not only hotel rooms but photographs themselves.

“Thomas Demand seemed to be provoking a type of reflection, and presumably insight, that only comes about through displacement. Demand gives, prescribing the vision, as he says, and Demand takes, handing you the moment and at the same time cutting it away. The subject in the photograph is a construction. It has an aura of reality but at the same time it doesn’t add up. It’s the slightly disturbing, preternatural silence of the spaces that exist either side of these disconnected moments that I find overwhelmingly seductive.”

Another disorienting photographic incursion into “that familiar otherworld of the hotel room” is witnessed by Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter in Guest Relations (Stills Gallery, 2013), a series of photographs by Robyn Stacey where “inverted cityscapes hover spectacularly over human figures at rest,” with a marvelous sci-fi strangeness wrought by the ancient pinhole camera technique. This review shares with other RealTime responses to photography a powerful immediacy, a sense that the writers are engaging with something beyond mere representation. It stems perhaps from photography’s basis, however attenuated, in reality; the fact that light must hit something material in order for a photograph to exist. It’s also a testament to the magazine’s encouragement of reviewing that, while thoughtful and analytic, derives from personal experience.

RealTime’s general focus on interdisciplinary artforms also serves its critiques of photography well, given the fascinating slipperiness of the medium (Jorgensen’s “category confusion”) as well as the prominent performative element in much contemporary photography. Broader overviews from writers highly literate in the form (Sandy Edwards, Darren Jorgensen, Robyn Ferrell) provide valuable context, while profiles of individual artists show how the medium continued to be extended and manipulated, producing startling perspectives on history, identity, materiality.

–

Read about photography in RealTime from 1994-2004 in Katerina Sakkas’ “Visual Arts, RealTime 1994-2004: Part 2, Convergence & Resurgence.”

Top image credit: Christian Thompson, Purified by Fire from the Lake Dolly series, 2017, image courtesy the artist

A critic sits reflected in the eye of the artist. Each review is a fragment of autobiography, if it is honest. “My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears and true plain hearts do in the faces rest,” wrote John Donne in The Good-Morrow. The more one writes, the more complete the self-portrait. What can I say about myself that can’t already be deduced from the criticism? What else do I need to say?

I write about dance, books, theatre, music, visual art and who knows what else. I teach at the VCA and am a researcher at the University of Melbourne. I began writing about art as a blogger, a proud amateur, and I suspect that there will always be a trace of ineradicable crudity about my writing, something imperfect and unprofessional, no matter how much I try to smooth it out.

I began writing for RealTime in 2012 and I’ve had some of my happiest art-going experiences as a RealTime correspondent. This is an incredibly important publication, perhaps the only masthead in Australia that is meaningfully committed to engaging with the messy multiplicity of contemporary art, across walls, screens, stages and everywhere else, here and around the world.

Website: neandellus.wordpress.com

Exposé

There are always plenty of people standing on the sidelines, shouting about the ethics of arts criticism and the responsibilities of the reviewer. I’ve done a fair bit of this myself. Over the years, I too have proffered many (often contradictory) opinions about what criticism should or should not be. For the moment, I feel like the best thing is simply to get on with doing the criticism.

Of course, it’s good to do the basics well. It’s important to name as many of the artists involved as possible and to pay attention to their different contributions. It’s good to give a sense of what it was like to actually be there, in the same room as the performers. And it is good to describe the bigger cultural picture, and the way that the performance resonates with that in terms of its value and meaning.

Yes, all of that should be sufficient. But the trick is to be more than sufficient. The trick is to say something really true, something about the work that is not easily sayable, that needs to be wrestled with. Does this mean that the critic should also be an artist, or like an artist? I don’t know. It’s a thing that people say. But I really don’t know.

Recent articles for realtime

Speakeasy: A question of independence

Natalie Abbott: some other swan

Christian Thompson’s performative self-portraiture

Emily Johnson, SHORE in NARRM: A line to cross

Jack Ferver & persona

Other RealTime writing

Persona

A Drone Opera

Richard Murphet, Quick Death/Slow Love

Interview: Ho Tzu Nyen, Anouk van Dijk, ANTI—GRAVITY

Christian Thompson’s performative self-portraiture

For other publications

Beyond the Skin: The Essays of Kobo Abe

Patrick White: A Theatre of His Own

The Poetry of Bruce Dawe: Blind Spots and Kevin Almighty

Seamus Heaney’s Virgil

Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below

I’d gone to university in my 30s — family man student — and was now into a PhD in Psychiatry (not Clinical). My supervisors used to scrutinise my writing for signs of something interesting and get me to rewrite again and again and again until anything that could in any way engage a reader or indicate human thought was expunged. Old school behaviouralists, as against new school materialists like me.

Then the first call came from RealTime asking if I’d like to review a couple of books themed with AI and neuroscience for their online-only section. I think I wrote about 1500 completely over the top thank-god-for-creative-writing words which were politely returned with a request to cut it to 500. Hooray — not a rejection ?. So I did the cut and from then on, through most of my time as a RealTime writer, I made significant efforts to hit the word count spot on — which I did within a word or two for most of my reviews. I took the word limit as a deliberate constraint, like writing without using the letter “e” (which I could not possibly do, lacking all motivation for such a task, although, in truth, my ridiculous curiosity has a way of driving my working habit toward such goals. Is this a sign of mistrust in individual worth — giving up on a natural flow of words for artificial and binding constraints…who knows?)

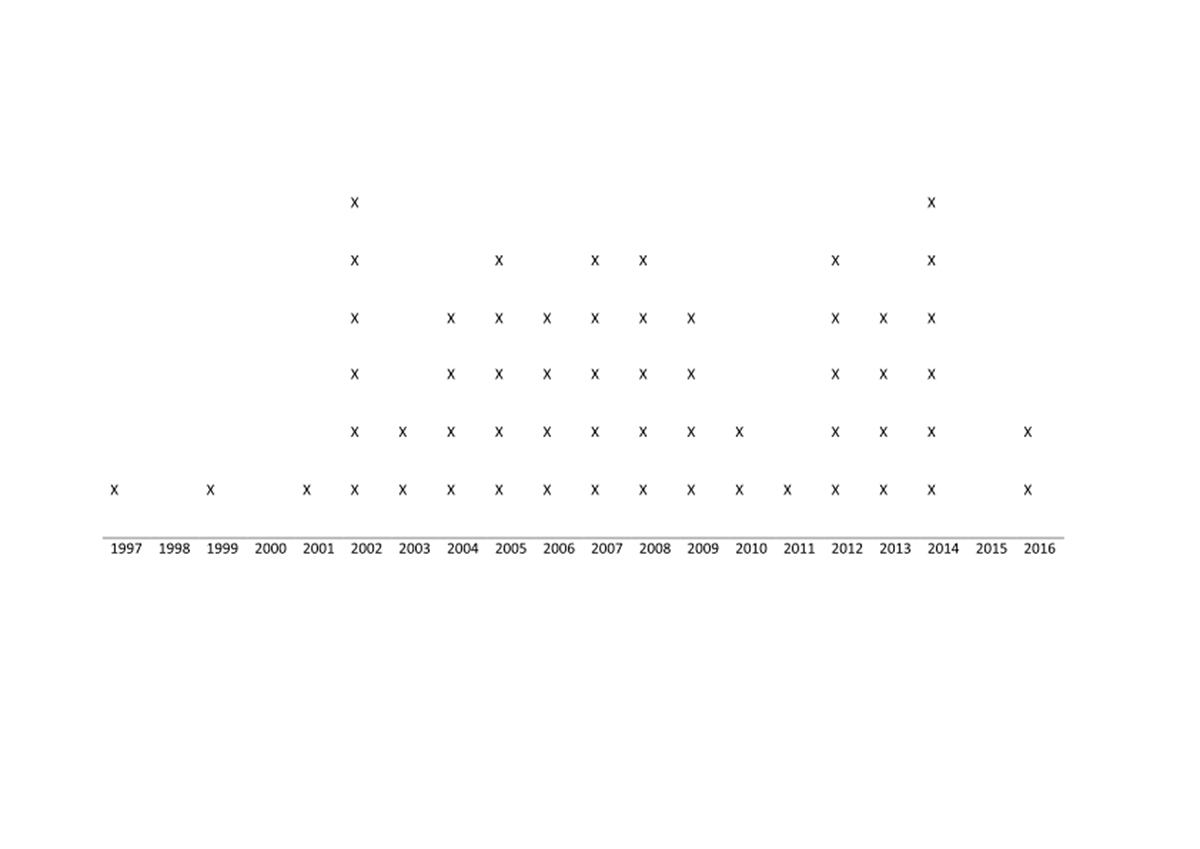

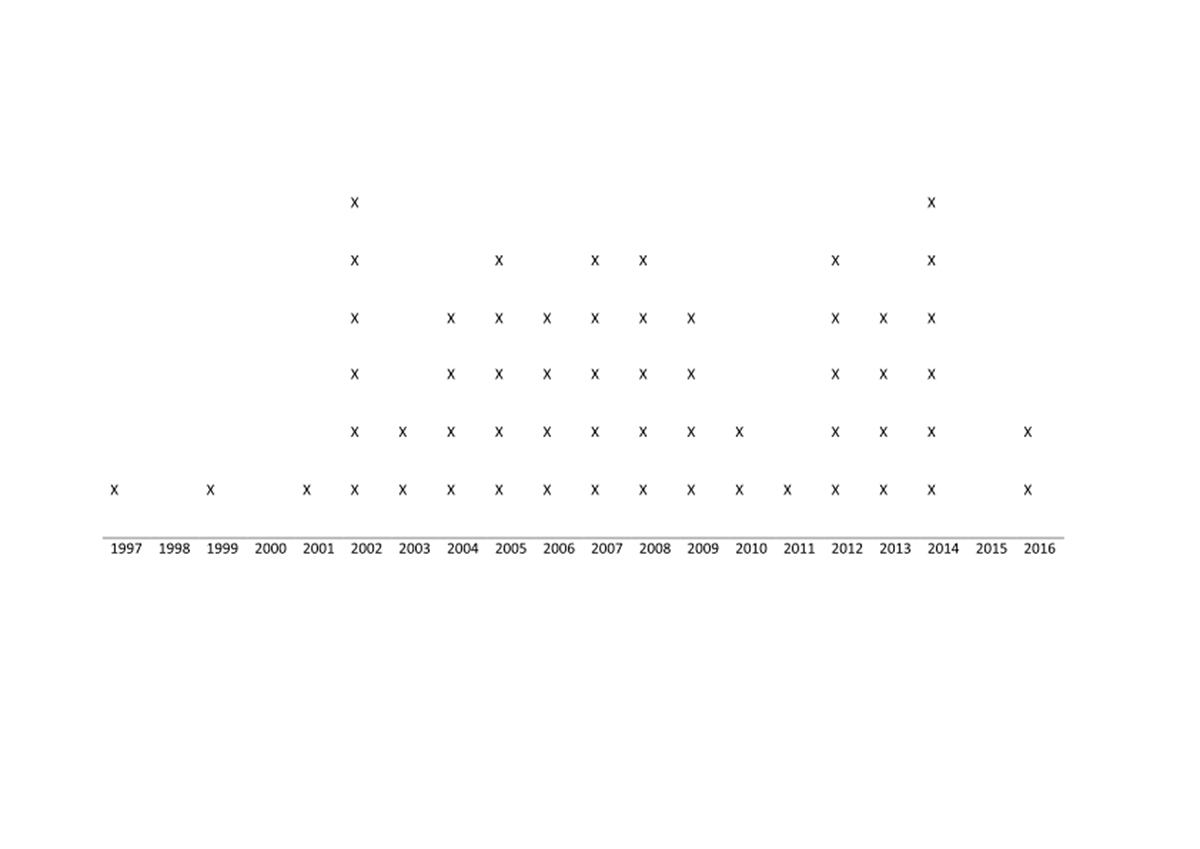

Figure 1 Histogram of number of RealTime reviews per year

The above histogram has a mean yearly number of articles of 3.41 with a standard deviation of 1.77 and is essentially meaningless without knowledge grounded in the way in which RealTime decided on the need for a review from Brisbane and the types of work being shown in Brisbane. Having that knowledge would make the histogram redundant.

To the writing

It begins with email: Greg, would you like to review concert/exhibition/festival, xxx number of words by xxx date for xxx dollars? Sure, I reply. Then I look to see what it is I will be reviewing. Accepting everything recommended gave me the opportunity to see something new, to get out from behind the computer and to escape the tedium of my academic life.

[Aside] I was not always successful getting to a performance — I once missed a one-on-one narrow timeslot of what looked like an interesting piece of installation theatre when I could not get a park within a kilometre or so because there was a community festival on that I had no idea about. Another time I couldn’t even find the venue (semi abandoned shop in a light industrial wasteland) — and I tried hard to find it, so I don’t know who got to see the performance, outside the friends and family set. [/Aside]

On the way-more-often-than-not times I made the show I’d sometimes bump into artists and chat, but mostly not. The Brisbane art world is small and many a time I felt a little socially awkward as “the reviewer.” I know some thought I was being standoffish, but it was just embarrassment. Some artists — particularly musician Erik Griswold — were open and chatty. Most are focused on setting themselves up to perform.

Once I was chatting to an artist — not even at one of their shows — and the person I had come with said afterwards, “Wow, they were really sucking up to you.” I had not noticed and still don’t think it true. Only a couple of times did I feel someone was being a bit of a jerk and trying to smarmy up for a review. Shame I was so obtuse, as I might have been able to leverage that to my own advantage if I hadn’t grown up in the old days, before the state-sponsored conflation of self-seeking and What would Jesus do?.

The bell rings and in we go: writing in the dark, notebook on lap, eyes on the stage is an acquired skill. As is the subsequent reading of notes.

First printed review was in RT34, p22, about Sci-Art ’99, which included a work by Adam Donovan (see top image). The event was an offshoot of MAAP 99 (Multi Media Australia Asia Pacific), an adjunct to the Third Asia Pacific Triennial (praise be to the APT). So long ago I could write about the curator: “Paul Brown is the only person I’ve met with a domain name: paul-brown.com.”

And couldn’t help myself with: “Of course soon everything will have a domain name. Then the fridge can tell us there’s a rotten tomato stuck in the frost at the back. A future of inescapable home truths. The phone will ring, ‘Who is it?’…’It’s the fridge’.”

ELISION Ensemble rehearsal, Wreck of Former Boundaries, 2016

A year or two later and I reviewed the contemporary music ensemble ELISION for the first time, in RealTime 49. I was stunned by the virtuosity of the performers, with “a failure rate any machine would envy. It’s easy to get used to the enormous polish that excellent performers have.” — a feeling that has never left me. But I was also critical of a couple of pieces for lacking coherence: “There’s that whole old school avant-garde thing: which of these two random sequences do you prefer? It’s an approach to composition that runs through the entire concert program. From an information/theoretic point of view, there’s a lot of information in random sequences. From a musical point of view, there’s none.”

That’s a view I’ve maintained and is supported by quite a bit of academic research — music plays with the creation of patterns of expectation, it’s probabilistic and if the music is just one thing after another, without any internal or external referencing, there is little probability of it working.

There were a few concerts I did not enjoy. Nothing to do with the style or my taste or a few mistakes but more to do with that artist not respecting the audience’s time. Respect needs to go both ways (the reciprocity/golden rule/civil society thing). I get annoyed taking time to see someone who isn’t trying or presents with contempt (perpetuating the artists-are-so-special trope) or has not done their homework to give credit to those who went before. This is as much to do with curators as artists — curators should weed out the most obvious crap and consult with others where their own expertise is lacking. I find a lot of science/art trite. My medico colleagues would say they did more interesting body work every week — and they did – or ethicists would point out that unnecessary operations in bio-art are unethical as they tie up resources that could go to people who actually need medical care to relieve harsh and overwhelming suffering. Grrrrrrr!

Figure 2. While the artistic intentions may be clear their reception is not always positive.

The critic may respond to a poor performance by writing something critical, avoiding saying much about that particular piece, trying to find something nice to say (perhaps about the venue or the finely tuned motor skills of the performer) or, rarest of all, apologising to the editors for not submitting — perhaps the reviewer left early, fearing the onset of overwhelming fatigue and the ebbing tide of joy.

Overwhelmingly I loved reviewing and the worst thing was not always being able to immerse myself in some astonishing work or other but instead be trying to think of something to note down. “Sometimes reviewing a concert can be a drag — maybe the work is just not that interesting, or the performances not that good and it is hard to think of anything to say. But sometimes reviewing is difficult because the concert is such a pleasure that I really don’t want to be listening-to-write, I just want to sit back and enjoy the unfolding moment. This was that sort of concert.”

By the latter part of my reviewing I was recording concerts so that I could enjoy the moments then go back and listen to the (pretty crappy) recording again as a reminder. Occasionally I revisited video works or borrowed a copy from the gallery to look at at home but I do wish I had thought of recording/revisiting/borrowing earlier. More than that I wish art videos were not restricted to galleries. There are so many wonderful videos that are not out there in the world — not on Vimeo or SBS or the mainly full-of-shit YouTube. But I understand the commercial imperative.

Here’s a joke the artist Richard Bell cracked the other day at the opening of the new Josh Milani Gallery:

“Do you want to hear a joke?” Sure. “Capitalism”

Opening lines

I started every review in the hope that an opening line would fall onto the page with so much momentum the rest would write itself. Never happened but every so often I managed to come up with a decent opener, or even a whole paragraph. This one for the music ensemble Topology in RealTime 51 is probably my favourite.

“Lordy, Lordy, Praise be to Jesus. Cut your throat now life doesn’t get any better than this. Topology. Corridors of Power. Brisbane Powerhouse.”

At the time I was sure it was a reference to Aristides the Just. His two sons had won at the Olympic Games and the crowd called this out. But scanning the net today it seems it refers to Diagoras of Rhodes, a boxing legend of the 5th century BCE, whose fame is so enduring he has both a footy club and an airport terminal named after him. One lucky year two of his three sons won at the Olympics, and he was carried around the stadium on the shoulders of his victorious sons. Someone in the crowd called out “Die, Diagoras; you will not ascend to Olympus besides,” meaning he had hit peak happiness for any and all possible mortals. Diagoras took that wise advice and died on the spot and has evermore been considered the happiest man who ever lived.

And he left a tomb which was worshipped as the resting place of a Holy Man. Until about 40 years ago the locals discovered it was in fact not the tomb of some worthy holier-than-thou but instead the tomb of Diagoras, The Happiest Boxer. Naturally the locals took umbrage and looted the tomb. But the Diagorian contribution to history does not end there. His tomb had an inscription that read “I will be vigilant at the very top so as to ensure that no coward can come and destroy this grave.” A Mighty Oath! But not effective, so now we know there is an upper bound of about 2500 years to the power of a Mighty Oath. Something to keep in mind for the future.

Terry Riley

Another opening

“There’s a certain kind of person who likes to ride in the bulletproof car, look out on the squalor and the roadside lifers, the trash-pile pickers and the sump-oil gleaners and think, that’d be me if I wasn’t so good. Terry Riley is from the other end of the distribution.” Hear and now: Terry Riley in Australia, RealTime 73

This little intro takes me back to my teenage years and going to a school friend’s house for the first and pretty much only time. The place was clean with biblical tracts upon the kidney-shaped timber side tables. Dad was conventionally chubby, bald and glad-handed. Middle manager worked his way up in Sales. Mum was tall with tightly controlled hair, fully buttoned clothing. They’d just got back from the Philippines and anecdoted the story of travelling in limousines through the rubbish dumps filled with children, the streets with distraught beggars. They loved it. Finally they were rich, no longer the ones on the bottom of the pile, surely a sign of God’s grace. They were heading off to church as I arrived and after they left we went in to the kitchen to get a drink. It was the classic kitchen, benches along the walls, cupboards above the benchtops. And all around, shoved between the cupboards above and the benchtops below, was years of kitchen rubbish. Old tins, empty Wheaties packets, wads of stained paper towels, thin hard plastics. Wedged in hard and tight until not a crevice was to be found.

My friend went on to become a junkie, did time, died alone on his remote bush block. His brother became a sniper for the ADF.

More openings

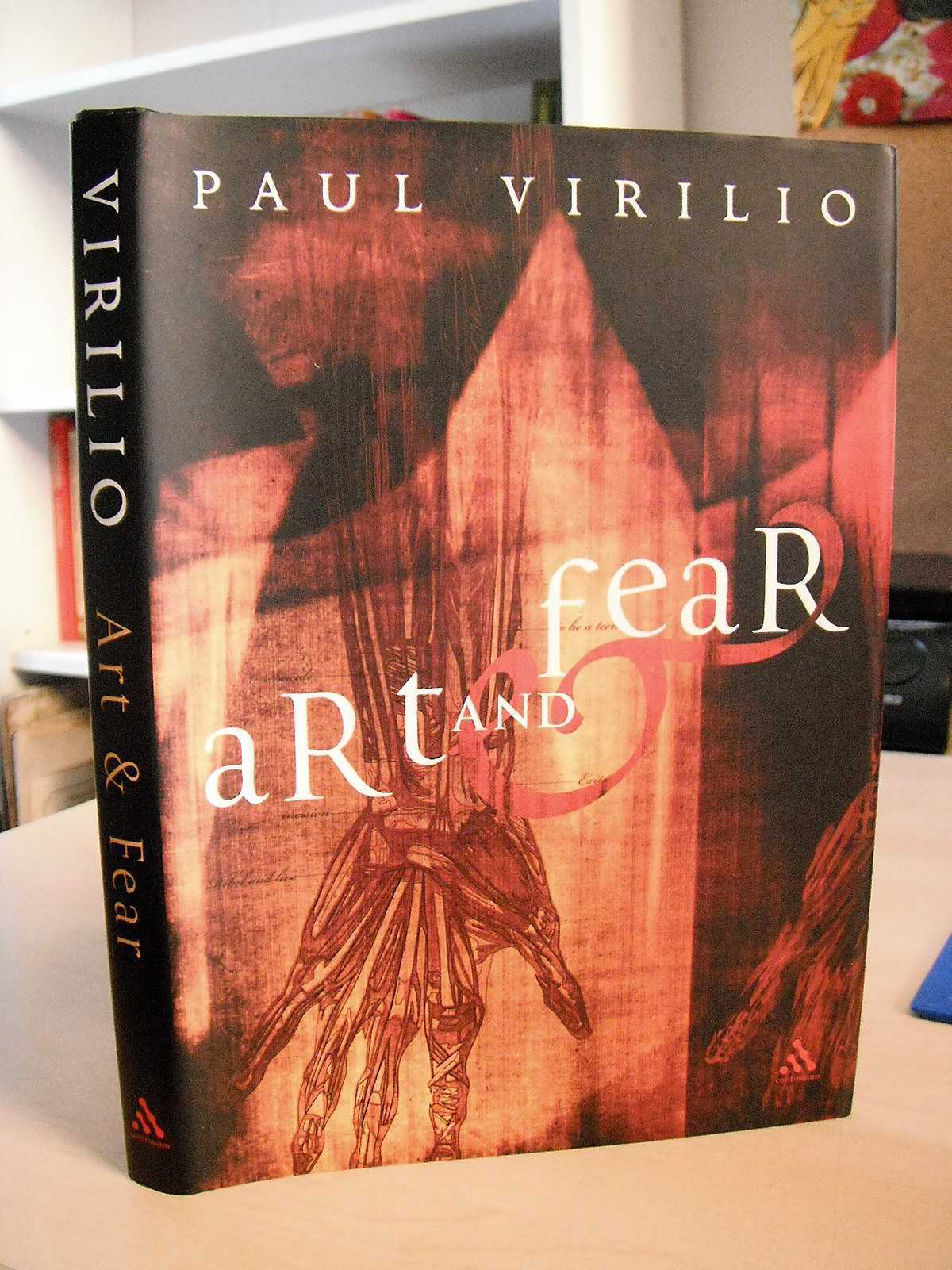

Science & the fear of art, RealTime 60: “Paul Virilio, culture theorist, architect, claustrophobe and asthmatic, sits high on the ridge, communing with the supernatural and looking down on the herd below. He sniffs the wind, scouts the boundaries, stares into a wide open sky that’s blue as the eyes of the white-boy Jesus. ‘They don’t know what’s a-coming,’ he thinks, looking down on the brutes below. ‘There’s poison up ahead’.”

Hybrid reading, RealTime 68: “There’s a standard in detective shows — bring in the Profiler, get inside the criminal’s head, root out that psycho-consciousness. ‘See those bite marks, that misplaced shoe-tree. We’re looking for someone who loves their mother’.”

Syzygy Ensemble

Nice Endings

With all the freedom RealTime offered a writer I still missed the boat with a catchy opening more often than not. Which doesn’t segue all that well into….Nice Endings, of which this from a review of a Syzygy concert RealTime 122 is my favourite by far:

“To finish is David Dzubay’s Kukulkan — six short movements programmed around the structure and use of a Mayan temple. Program music can sometimes get a bit stolid and prog rock or sentimental and twee, symbols grinding away as surrogates for far too fraught emotions. I don’t get that with Kukulkan. Instead, there is more of a cinematic wash to each movement. Forbidding piano and spooky clarinet sound like a 30s mystery, dimly lit passageways, a man with a hat, a door opens and the glimpse of a gun. Or next movement and switch to light, joyful 60s and the end of austerity Britain — young love at Oxford, the student and the shopgirl ride through the square and scatter the pigeons, punt along the river, plop down on the grassy bank for that very first kiss. Except it’s Mayan, human sacrifice, hearts held aloft.”

Kukulkan was played in a concert in a coffee shop and had within it much that has been good about the evolution of musical performance in Brisbane — performance as a genuine and natural social occasion. In this case a bit of show-and-tell at the start from two of the performers:

“In the neat preparatory talk, Harrald and Khafagi play us the original tunes Charles Ives used for each of the three movements: ‘Tell me the old, old story,’ ‘Yes, Jesus loves me’ and ‘Shall we gather at the river?’ Performers often introduce pieces with a short description of the composer’s intent or perhaps a formal aspect of the music, but this is perhaps the first time I’ve seen performers actually play examples in their discussion.”

Topology

Topology were big innovators in approachability in Brisbane — Rob Davidson led the way in the first concert of theirs I reviewed: “One of the things I like about Topology is their insistence on communicating with the audience. Their program guides have notes on every piece, and URLs for some of the composers and also for the band. Often one of the performers will speak a little about the piece they are going to play, but chatty, not too Adult-Ed. And because they premiere a lot of works (tonight is no exception) it is often useful.”

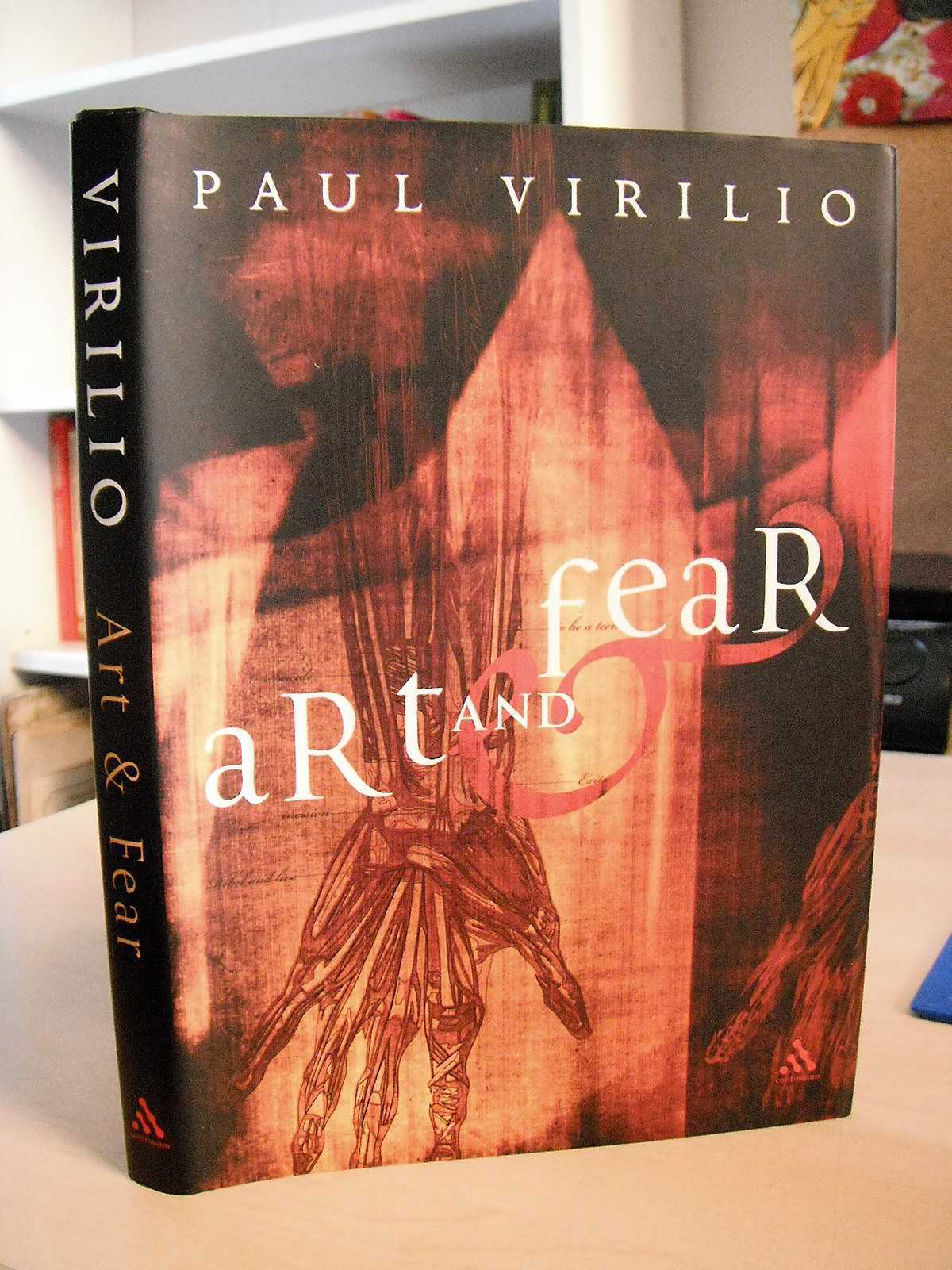

Art and Fear, Paul Virilio

Big Themes

Having a science background I could not resist a little Adult-Ed myself, trotting out my thoughts on cognition whenever I found the tiniest crack to jemmy them into. Not so hard to manage in this review of Virilio’s Art and Fear, and Stephen Pinker’s The Blank Slate. Specifically dealing with art and science the entire review is pretty much a personal take on how art works (as well as poking fun at Virilio).

“Virilio senses that the absence of the body in Abstraction leads to the absence of the living body through suicide, and the distorted images of the body in Expressionism encourage the torturer to distort the body of the victim. It’s the slippery slope argument, and for Virilio that slope leads art down into suicide, torture and genocide, so that ‘The slogan of the First Futurist Manifesto…led directly to the shower block of Auschwitz-Birkenau.’ If he is right and art after Impressionism is responsible for all these things one wonders what the causes of suicide, torture, and genocide were during the long years before the 20th century and in populations completely isolated from European art history.”

Pinker is much more reasonable but confuses his taste for a Universal. How many times does this happen (roll eyes and groan — use denial to pretend I don’t do this myself).

“Pinker’s use of behavioural genetics and evolutionary psychology to shed light onto the existence and function of art production and consumption is pretty interesting. But then Pinker goes too far and claims it all went horribly wrong with modernism and postmodernism. Artists stopped pandering to the evolutionary limits of perception and cognition. They stopped going for realism, started painting outside the lines, that jazz don’t swing no more and who can find a tune worth whistling. Besides, art theory is for wankers and nobody listens to the critics anyway. As is common in arguments touting the ‘Once was an age of gold but now is in an age of mud’ theme, there is a whole lot of edited highlights of history going on. Pinker has found a bunch of art that doesn’t communicate to him and then generalised that to elite art doesn’t communicate to anyone worth knowing because elite artists flout evolutionary constraints on communication. He has oozed over from science to taste without noticing the transition.”

Perlonex, LA 10, Brisbane, 2009 (RT92)

Ethics & loud music

As part of my science/academic career I sat in on/set up/chaired ethics committees and that, plus my association with medicinel got me irked at how loud a lot of concerts were; some performances were way over the threshold for damaging hearing. But I noticed a change starting around 2002, when I introduce another theme that stayed with me across the years: ethics of performance:

“Warning signs plaster the theatre doors ‘This is going to be loud.’ Now I’m a big fan of ethics in performance and don’t see why tissue damage should be a part of the audience experience.”

It gradually improves, in RealTime 92 to venues offering earplugs: “A woman at the front desk asks my son if he wants earplugs. He leans over to me and asks, ‘What sort of concert needs earplugs?’ One that is, at times, far too loud. Maybe at times loud enough to constitute assault and loud enough to contravene appropriate codes of conduct as laid down by somebody somewhere. I don’t know. When it got loud I closed my ears, all the better to hear another day.”

Although I am not sure they were available for Liquid Architecture 13: “but then it gets stupid loud and sensible types in the audience all start shoving fingers in their ears — which would make a nice photo.”

Preamble to The Quick Ending

Staying on topic can be a struggle — not just in reviewing but in conversation and not just in conversation but also in thinking. Which brings me to Star Trek — original and Next Generations where timing was everything. Forty five minutes building up an interesting, seemingly insoluble conundrum, military or ethical, and then suddenly, like a man on the building’s edge, Kirk or Picard or whoever had the chair would look at their watch and go, “Oh my goodness is that the time, we only have five minutes to get this show finished,” and the story would collapse into an heroic and virtuous solution with merest seconds to go before the credits rolled. ” It’s the same with reviewing, although I am not sure why.

The Quick Ending

Margaret McCartney bowed out of her column for the British Medical Journal the other day with a list of “wisdoms”. I’ve always been partial to a one liner myself:

Bentham’s statement of compassion: “The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

The variously attributed idealism of “There is another world, and it is in this one.”

The consumer materialism of “no deposit, no return” (and the corollary “self-serve”).

The Italian village critique of history and culture “New wave, old water.”

My father’s observation that whilst growing old was no joke, dying young was not appealing either.

And my current favourite for critics, pundits, public intellectuals and personal optimisers everywhere

“If you can’t think of anything nice then don’t think of anything at all.”

–

Top image credit: Phase Inversion, Adam Donovan courtesy the artist

Embracing a 1997 proposal to eliminate ugliness from public spaces in time for the 2000 Olympics, RealTime columnist Vivienne Inch proposed sport take a good look at itself.

Tee Off with Vivienne Inch

Teeing off with Councillor Sam Witheridge at the Kogarah course this week, I was effusive in my praise for his magnificent solution for bringing our embarrassingly untidy city up to par for the 2000 Olympics. The Councillor will be seeking support at the Local Government Association conference in October for all councils to impose fines up to $10,000 for illegal postering on public buildings. Brilliant! We need more ideas like this. I suggested that Sam have a yarn to Olympics Minister Michael Knight who is, of course, desperate for a revenue grabber to offset the miserable sales of his corporate boxes. The “Green Games” concept is clearly an albatross. What about the “Tidy Games?” It’s so Australian. I can’t wait for them to move from ugly posters to ugly corporate logos, ugly merchandise and, inevitably, ugly sports. Weightlifting, for instance, seem to attract a short-arsed, hairy sort of a person, sprinters are all skin and bone and have no dress sense; rowers go red; swimmers get wet; the marathon is a disgusting display of human indignity. Let’s face it, only golfers know how to show off a range of co-ordinated sportswear while remaining viciously competitive.

–

RT20, Aug-Sept 1997, p42

I contributed to RealTime Australia from 1998 up to the present, with a dip in contributions while I worked in New Zealand, 2009-15. Looking back over my involvement, I am struck by the diversity of work, style and material which both I and the magazine encompassed. While RealTime had stylistic trends, there was a notable period where meditations on one’s personal psychophysical response as an audience member were common though I myself only rarely embraced such an approach (as in RT 35 in 2000).

The magazine was a Catholic church. As such, it offered myself and others opportunities to not only author close-study, expert reviews, but also to regularly tackle the near impossible writing challenge of drawing together in one thematically-linked article six or so disparate works within, for example, the Melbourne Festival, or of the last two months of dance in Perth, all in less than 1,800 words! I also had the opportunity to write occasional features and opinion pieces. These longer works arose less as editor-led commissions and more out of what I, as a contributor, thought might be useful to add to arts discussion in Australia. Because of this, those pieces were very important for me, typically coming out of major developments in my own career as a critic and arts researcher.

Massacre, Not Yet, It’s Difficult

My 2004 trip to Japan, for example, my increasing investment in the DIY noise art culture of South Island New Zealand, or my 2003 trip alongside the members of the performance company Not Yet, It’s Difficult to the Vienna Festival; all led me to significant philosophical developments in my own viewing of performance.

Because of this tendency for my work in RealTime to function more as a form of dialogue, than as definitive statements, I have in retrospect noticed that quite a number of the shows which I remember best today were not in fact the ones I actually wrote about directly myself. Rather these productions tend to be ones for which I knew the reviewers, or the artists — often because I had covered their work elsewhere (most notably in the Melbourne street press, specifically IN Press Magazine, for which I authored material 1992-98).

Looking back now therefore, it seems to me that while the reviews that I and others wrote for RealTime provide an indispensable archive on the performing arts in Australia, I have always thought that what we were contributing to was principally more of a contingent, multi-directional conversation — rather than these pieces functioning as definitive records as such. Through my work as a critic, I met and spoke with a range of artists, many of whom I am still in correspondence with today, and quite a number of whom are now friends. My academic work dovetails closely with these relationships and with those thoughts which I developed through my involvement in RealTime. All of this led me — and probably some of the artists I encountered —to where we are today. This might be related to the rather opaque relationship RealTime had with its readership. It was never an academic magazine, but it was not an entirely non-academic one either. A great many of its writers (myself included) had worked within the university sector. I have always hoped that my work would be read by deeply interested laypeople, though not necessarily the general public per se. RealTime’s house style was not typically an “easy read”; closer perhaps to Laurie Anderson’s wonderful championing of the “difficult listening hour” in art music. I always felt therefore that RealTime was principally addressed to those who followed the arts closely, those who had already decided that they needed to know what the next cutting edge dance piece, or challenging sound installation, might be. Consequently, many of these readers were in fact the artists themselves, and this is often what made writing for RealTime — and indeed my ongoing arts criticism in Limelight and Seesaw magazines — so exciting and rewarding. One felt part of an often fractious and certainly opinionated, but wonderfully interactive, community of individuals who were collectively engaged in a complex series of debates and exchanges regarding the nature of Australian culture and its place in the world. While the vital contribution RealTime makes in the present to this important project now proceeds via a an historiographic encounter, rather than directly commenting upon the now we currently inhabit, it is no less important today.

Falling Petals, Ben Ellis, promotional image Jeff Busby

FAVOURITE & PROBLEMATIC WORKS/EVENTS

Ben Ellis, Falling Petals, 2003

An important part of RealTime’s function has been to cover that which then still powerful mainstream media did not, or to provide added depth to such coverage where the major daily newspapers were either unable or unwilling because of editorial constraints. Ellis’ remarkable play Falling Petals (see my review), together with his earlier piece Post Felicity (2002), were savaged by several major critics as too nasty and too unlikely. How could people really behave this way? Surely drama needs “relatable” characters? This was shortly after the Children Overboard incident (so well dramatised in Version 1.0’s A Certain Maritime Incident), which had many in theatre calling for the “great Australian play” that would deal with the topic of refugee rights and loss of liberty due to anti-terrorism legislation — failing to note the obvious contradiction of writing a “great play” about something so hateful, complex and over-determined as the decline of political empathy in a nation beset by fears of outsiders, disease, a potential drop in the balance of trade and other issues.

The quality of the play that I strove to capture in this piece (which I still think reads well today) is that illogic, contradiction and a blasé approach to the rise of hate and self-interest, which not only lay at the heart of this play, but at the centre of the new Australian malaise we had all come to live with at that time (and still do today). Within Ellis’s insightful, dark vision, a country town and its school leavers are thrown on the pyre of political and economic expediency and no one really cares. The production also featured one of the most fabulously Surreal scenes in Australian theatre, where the doctor treating the strange disease which emerges within the school is himself turned into a giant walking vagina, cruelly and erotically sensitive to all he had previously striven to deal with in an objective, distanced fashion. It is only the unscrupulous protagonist who survives. Who knows, maybe he went on to become prime minister?

Ben Ellis’s play therefore not only turned a wickedly distorting carnival-house mirror onto the Australian cultural and political scene, but also challenged me in how to respond, how to sum up its manifold contradictions and its deftly handled conflation of horror cinema and Australian domestic drama. In the end, I chose to go with the rage which I felt the piece epitomised, the angry, violent sense that something horrible is ripping through my country and no one can stop it. I’m not sure things have changed that much since.

Michelle Heaven, Brian Lucas, Tense Dave, Chunky Move, photo Anthony Scibelli

2003 Melbourne International Art Festival dance program

In 2003 I reviewed the Melbourne International Arts Festival program, which included works by Gideon Obarzanek’s Chunky Move, Sandra Parker, Tony Yap and Yumi Umiumare. I have been privileged to be on hand during several important developments in dance in Australia. In Perth I saw exciting early works from Aimee Smith (now no longer making dance), Paea Leach, and Olivia Millard, while in Melbourne I witnessed the evolution of Lucy Guerin, Ros Warby, Phillip Adams and Rebecca Hilton after they renewed their Australian careers with the landmark mixed bill of Return Ticket, reviewed by Zsuzsanna Soboslay.

Helen Herbertson‘s fabulous productions became more installation-based and episodic, swimming within designer Ben Cobham’s great swathes of blackened space and punctuated by indistinct penumbral realms into which bodies infiltrated themselves (Descansos, Delirium, Morphia). Gideon Obarzanek’s Chunky Move came to Melbourne. Shelley Lasica staged her truly jaw-dropping and inordinately thoughtful Situation studies, reviewed by Philipa Rothfield, while Yumi Umiumare and Tony Yap — both together and in isolation — emerged as leaders of a multicultural, multiethnic Australian post-butoh movement. I reviewed works by Umiumare and Yap here, here, and here. See also John Bailey’s review of Umiumare’s DasSHOKU Hora!.

And then there was Sandra Parker. Sandy’s choreography immediately sat apart from those I list above, despite the fact that she, Shelley, Lucy and Gideon would all come to choreograph on some of the same dancers. Sandy’s work was usually more lyrical and curvilinear — although her choreography certainly had spikey moments of rapid, harsh shifts and aggressive folds. In retrospect, I wonder if it was more overtly feminine somehow (though I admit this only makes sense according to a rather conventional model of gendered antitheses). More significantly, the wider reception of Parker’s work always had a certain coolness to it. She had the unenviable task of replacing Herbertson at the helm of Danceworks at the point that the company’s financial status and home venue were in question, and Sandra’s own work was very different from Helen’s. Nor did her practice quite fit into the rising trend of bony articulations, together with highly muscular and virtuosic movement, which characterised the artists in Return Ticket as well as the rising force of Chunky Move. Sandy’s work just didn’t seem very postmodern, or even post-postmodern either. But it was still extremely good.

The article I have chosen here therefore draws together this rather disparate range of trends within Melbourne dance to examine one of Gideon’s most dramaturgically challenging works with Chunky Move, Tense Dave (co-choreographed and directed with Lucy Guerin and Michael Kantor), as well as briefly analysing the astonishingly intimate and nuanced collaborative work Yumi and Tony were doing at that time. But my article also highlights one of Parker’s masterful and to my mind still insufficiently appreciated works, Symptomatic. While I still consider In Absentia (evocatively performed in the now vanished industrial venue of Melbourne’s Economiser building) together with In the Heart of the Eye to be Parker’s masterworks, what challenged me about Symptomatic was the fusion of earlier physical concerns within an increasingly opaque yet still compelling dramaturgy — in this sense thematically far closer to Chunky Move’s Tense Dave than I had anticipated, even though the actual movement of the two pieces had almost nothing in common.

Symptomatic is an unusually aggressive work in Parker’s canon, providing compelling evidence of how she and the others I have cited above often suddenly produce something one did not expect (I recently saw Attractor, the wonderful piece from Lucy, Gideon and Indonesian musician Senyawa, featuring Dance North, in the 2018 Perth Festival, and I’m still struggling to reconcile its chaotic choreographic pulses with the cool formalism which previously characterised Guerin’s work. The idea of choreographers striving to develop with a singular, characteristic physical style could perhaps have faded today.

Symptomatic may not have fully resolved the ancient problem of how to suggest drama and emotion in movement without explicitly stating it in words. Symptomatic nevertheless retained an austere and evocatively unsympathetic mode of execution in its sound-and-movement configurations which paradoxically was quite moving. As I noted earlier, the best art is not in fact about producing gleaming, well-oiled machines which tell us little that we do not already know. Rather it should pose unresolved questions and promote interactions between audiences and others. My festival review captures to some extent this exciting and at times slightly fervid set of still-evolving exchanges, while also emphasising and paying homage to a dance-maker whom I for one would like to see more of today.

Jandamarra, 2008, Ningali Lawford, Margaret Mills, Kelton Pell, Tony Briggs, Jimi Bani, Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company, photo Gary Marsh

Learning from WA