July 2019

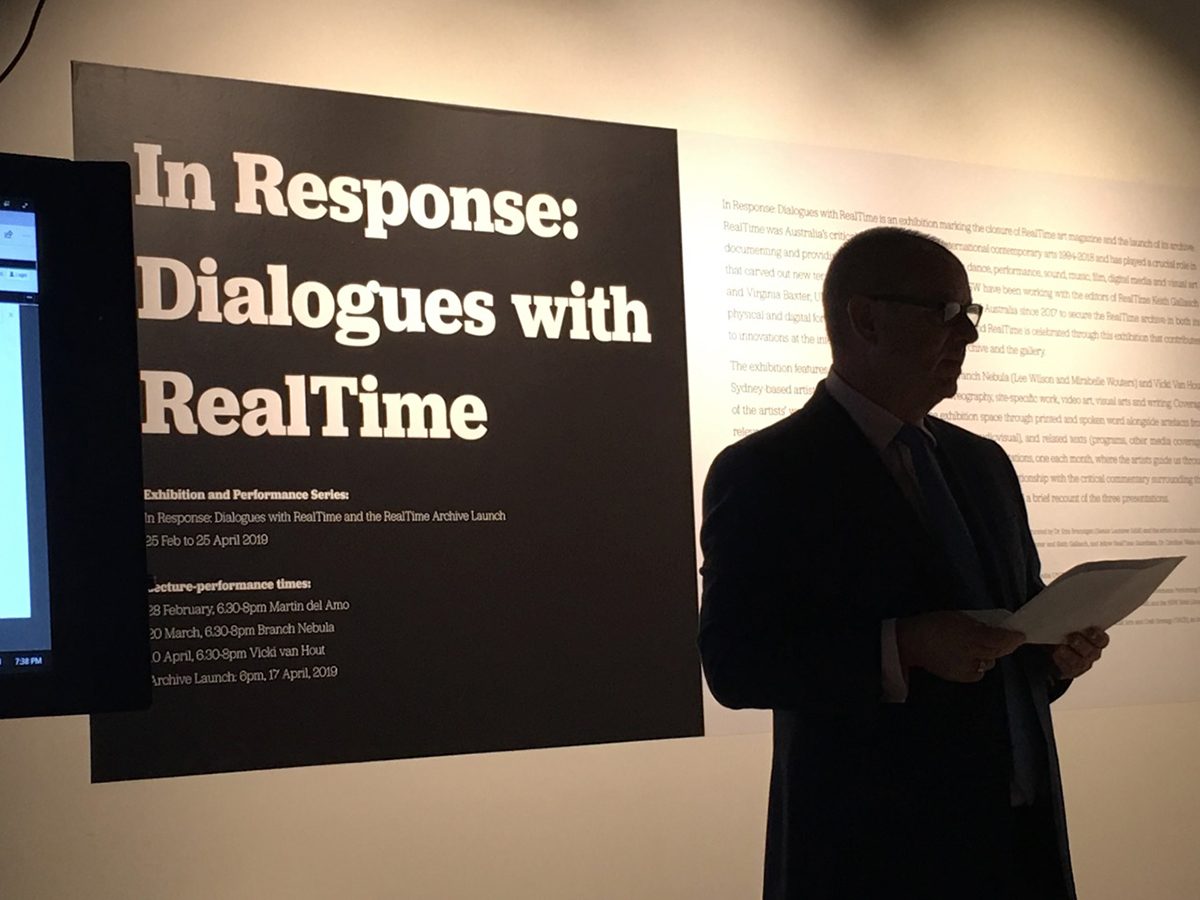

RealTime Extra. As we continue to refine and build on the RealTime archive, we thought you’d enjoy reading about the joyous launch at UNSW Library Exhibition Space by Professor Sarah Miller AM of the complete 1994-2015 print editions of RealTime on the National Library of Australia’s TROVE website. You can also read each of the excellent speeches by Sarah, UNSW Librarian Martin Borchert, Tony MacGregor, Chair of Open City, publisher of RealTime, and Jeremy Smith, representing the Australia Council for the Arts. It was a night of reflection, laughter and a few tears.

Adding substantially to the RealTime archive are contributions in this edition from long-time RealTime associates Caroline Wake and Erin Brannigan. Focusing on Sydney performance, art and refugees, and errant arts funding policies, Caroline looks back on the years she wrote extensively for RealTime. Erin, who commenced writing for us in 1997, bravely corrals RealTime’s enormous coverage of dance across Australia.

As well, we’re publishing two fascinating essays commissioned by RealTime towards the kind of book we need in this country. To be edited by RealTime contributors Jana Perkovic and Andrew Fuhrmann, the collection will focus on theatre and performance in Melbourne 2005-2015. Jana charts a diminishing preoccupation with ‘liveness’ across the period; Andrew personally grids the city according to his encounters with pivotal works at non-mainstream venues.

Although we’re working quietly and intermittently, we’d love to hear any queries or observations you might have about the RealTime archive. Special thanks to Sandy Edwards for the photographs of the launch. All the best, Keith & Virginia

–

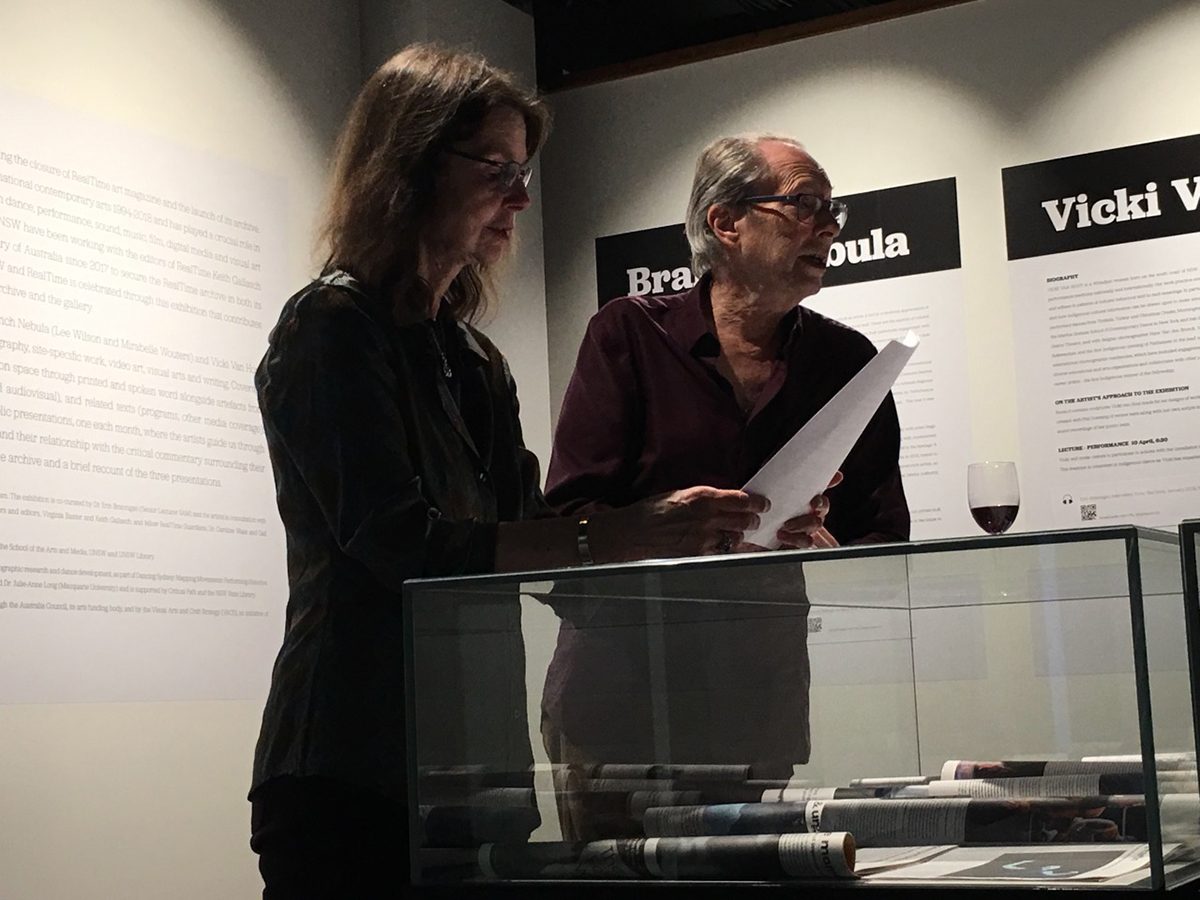

Top image credit: Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch at RealTime Trove archive launch, photo Sandy Edwards

The launch of the 1994-2015 print editions of RealTime on the National Library of Australia’s TROVE website was a memorable night of performances, reminiscences and wise words about cultural memory and the importance of archiving, inflected with laughter and a few tears. It culminated with Professor Sarah Miller, wielding a giant pair of scissors, cutting a red ribbon—held at one end by ourselves and at the other by UNSW Librarian Martin Borchert—before a large monitor displaying RealTime on TROVE.

- Mirabelle Wouters (Branch Nebula), photo Sandy Edwards

- Vicki Van Hout, photo Sandy Edwards

- Martin del Amo, photo Sandy Edwards

In the first part of the evening, Martin del Amo spoke to the value of RealTime’s analytic reviews and Heidrun Lohr’s photographs of his work and danced an achingly exquisite solo embodying the passion of Maria Callas in performance. Vicki Van Hout, accompanied by Henrietta Baird, resurrected in words and movement a fragment of Vicki’s vibrant Briwyant. Vicki then reflected generously on the significance of RealTime reviews for her career and for Indigenous dance. Mirabelle Wouters of Branch Nebula continued the dialogue with curator Erin Brannigan initiated in the second of the four events that comprised a significant part of the exhibition In Response: Dialogues with RealTime, observing that for part of the company’s career the magazine had alone provided vital critical support.

Real time RealTime dialogue

We then presented our own response to RealTime, a dialogue addressing the magazine that we made, but which in turn made us—hitherto actors and writer-performers—editors, publishers and reviewers of often remarkable art, art that further transformed us personally, as we engaged for over two decades with works innovatively preoccupied with real time, bodies of all kinds, the senses and the interplay of actual and virtual, across artforms and across Australia and beyond in collaboration with a network of highly responsive skilled writers, many of them artists.

We quizzed each other about what we had experienced in those years of “tough but unalienated labour, doing our bit for cultural sustainability in the face of escalating neoliberalism” and revelling in “lingering over lush surfaces. Lost for words, aching to respond, to what just happened. Not jumping to conclusions; not rushing to judgement, entering the eternal loop. Embracing the work, taking it home, letting it in, like a lover, or Alien. Exercising the mirror neurons. Dancing the dance. Writing the dance. Keep talking to the work, talking to self. What happened to me this time? Is it still happening?” (You can read our Real Time Dialogue with RealTime in the attached PDF.)

Martin Borchert, Librarian, UNSW Library

The second half of the event comprised a series of incisive, entertaining speeches culminating in the launch of RealTime on TROVE and celebrating the RealTime website. Martin Borchert, Librarian, UNSW Library warmly thanked the National Library of Australia and Dr Hilary Berthon for partnering the digitisation of the magazine, UNSW Library staff members Robyn Drummond, Megan Saville, Jackson Mann and Maude Frances. He especially thanked Erin Brannigan and Caroline Wake of the UNSW School of Arts & Media and Keith and Virginia for their collaboration with UNSW Library on the digitisation venture.

Martin Borchert spoke of two kinds of ‘value adding’ the exhibition offered: firstly a kind of ‘glamour’ thanks to the performative and installation components which enhanced visitor engagement for the new exhibition space, and secondly the ways in which the audio (artist interviews) and video (performance documentation) components made for the exhibition would be preserved and further the range and depth of the RealTime archive.

In the first edition of RealTime in June 1994, Borchert noted, “the editorial announced that RealTime ‘opens up the possibilities for writers and artists everywhere in Australia to contribute to the spread of information and ideas across artforms and distance.’ I think this archive really achieves that and it’s a long time since the journal started so it’s nice to re-visit that mission.”

Tony MacGregor, Chair, Open City Inc

Tony MacGregor, Chair of Open City, the publisher of RealTime, spoke to the power of archives, incidentally complementing Martin Borchert’s vision of more diversified preservation, by citing Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever (1995) in which the philosopher argued “that archives both shape and reflect the way we think, the way power is structured, the way we imagine ourselves, and that archives are changing, no longer vast libraries of documents recording the machinations of the powerful. They are becoming—must become—porous, heterogenous accumulations of multimedia. The archive can no longer be made of paper, but as we see around us is made up of all sorts of stuff. And, as the performances of Martin Del Amo, Branch Nebula and Vicki Van Hout over the past few months have eloquently demonstrated, the archive is often stored in the body, written in the flesh.”

Tony went on to thank the Australia Council and peer assessors of grant applications for their enduring support for RealTime, and UNSW Library and the NLA “for their commitment to nurturing the cultural history of Australia, not just in this instance, but in an ongoing and generous manner.” He reminded those gathered that it “was important to remember that Real Time was—is—an artists’ project,” “a collective enterprise.” “RealTime—and its editors and writers—have done more than serve a community, they have, in so many ways, made it. That is their gift to us (readers, writers, makers, audiences), and I thank them for it.”

Jeremy Smith, Australia Council for the Arts

Jeremy Smith, Director Community, Emerging & Experimental Arts, Australia Council for the Arts, recalled his first encounters with RealTime, picking up a copy in 1995 at Perth’s PICA, where Sarah Miller was Director. Later, as a young lighting designer, he received a positive mention in a RealTime review: “that’s what set Real Time apart—its editors, writers and contributors saw and considered elements others didn’t. It was as if they were always searching for new ground and looking beyond the horizon—the as yet unseen. They saw and wrote about the new aesthetics and hybrid forms, the delights for us audiences long before others, helped promote and increase our enjoyment, cultural literacy, plus stimulated collaborations and conversations.”

Jeremy reflected on the “robust relationship” between the Australia Council and RealTime, citing “the crucial role Real Time—especially Keith—has played as a critical friend of the Australia Council…highlighting in the magazine the Council’s ‘mistaken’ arts practice restructure in 2004 and 2005” (the passionately resisted dismantling of the New Media Arts Board). He amusingly recalled Keith’s deployment, in the Sydney Morning Herald, of an ecological model of the arts, with the Council as a threatening monocultural omnivore and innovative artists as humble slime mold—networking and shapeshifting. Jeremy observed, “underpinning that funding partnership since 1994 has been the endorsement and praise of countless numbers of peers from around the country who have validated the continued support of this crucial part of our ecosystem. That alone speaks volumes.”

Jeremy also acknowledged the presence at this launch of Andrew Donovan, Director, Artist Services at Australia Council for the Arts, “a significant contributor to the RealTime-Australia Council relationship and indeed the contemporary and experimental arts sector over many, many years.” Andy was indeed very welcome.

While lamenting the current absence of a national across-the-arts magazine, Jeremy noted “seeing pockets of the contemporary and experimental arts sectors—organisations and independent artists—responding in small, unique, considered and important ways to fill this void. I genuinely hope this continues.

“It’s never an easy decision to call time, and to windup. It takes bravery. I commend Keith, Virginia, the Open City Board and all of the contributors to Real Time for 25 years of bravery, courage, fierce articulation, wisdom—and change.”

Professor Sarah Miller AM

Professor Sarah Miller recalled reviewing Open City’s Photoplay in 1988 for Art Almanac and meeting us when, in the period of her directorship of Performance Space 1989-93, “Open City was one of the key ensembles working out of Performance Space. Ostensibly casual and chatty, but meticulously crafted, their work was distinguished by their collaborations with artists from a range of artform backgrounds, specialists from other disciplines and industries, and dealing with the politics of the everyday. Does this sound familiar?”

Sarah described the considerable challenges for artists in the 1980s and 90s in “refusing to conform to a bunch of fairly prescriptive ideas about what constituted real art, real theatre, real music, or real dance…” She recalled the Australia Council’s subsequent “establishment [in 1993] of the Hybrid Arts Committee—later the New Media Arts Board, now the Emerging and Experimental Arts Fund—which provided dedicated funding to artists whose work sat outside conventional parameters” (though not mentioning her own role as passionate advocate on Australia Council boards). Sarah then detailed outcomes of the RealTime vision: experiential writing, inclusiveness, free national access in print from 1994 and online from 1996, national and international perspectives for artists and readers, aided by review-writing workshops around the world.

Unable to resist the pun, Sarah described the NLA’s archive as a Treasure TROVE and thanked UNSW Library and the National Library of Australia for “making the TROVE RealTime archive an invaluable resource for Australian artists’ sense of their own and their collective histories, for inspiring students and emerging artists, for providing rich material for researchers and arts historians, as well as anybody curious about what happened.”

Before cutting the ribbon to launch RealTime on TROVE and our upgraded website, Sarah concluded her speech saying, “I really miss RealTime. It has been an essential part of my life for 25 years, and I know that’s true for everyone here tonight. There really aren’t the words—which is why I’ve used so many—to thank Keith and Virginia for their commitment, passion, rigour, tenacity and hard work, and above all for putting artists and their work front and centre. Absolutely mammoth achievement.”

Thanks

Sarah dextrously scissored the red ribbon, completing the launch, save for rapidly listed thanks from us to everyone who had performed or spoken on the night, to the NLA (and Dr Hilary Berthon) and UNSW Library (and Megan Saville), to RealTime website designers Graeme Smith and The Mighty Wonton, Open City Board members Tony MacGregor, John Davis, Julie Robb, Urszula Dawkins and Phillipa McGuiness, Assistant Editor Katerina Sakkas and Online Producer Lucy Parakhina, previous staff members (Gail Priest above all), to Erin Brannigan for In Response: Dialogues with RealTime and much else, Caroline Wake and, for creatively dialoguing with RealTime, special thanks to Martin Del Amo, Branch Nebula (Mirabelle Wouters and Lee Wilson) and Vicki Van Hout.

To all those who have contributed to RealTime over these many years—writers, artists, readers, supporters, advertisers and funders from across Australia and beyond—thanks for being part of the epic making of an intensely memorable, very much alive archive.

You can read the complete speeches and our Real time dialogue with RealTime here.

–

In Response: Dialogues with RealTime, Archive Launch, UNSW Library Exhibition Space, UNSW, Sydney, 17 April, 2019

Top image credit: L-R: Katerina Sakkas, Virginia Baxter, Gail Priest, Tony MacGregor, Keith Gallasch, Erin Brannigan, Sarah Miller, photo Sandy Edwards

From 2007 to 2017, over the course of roughly 50 issues (RT82-137), I wrote approximately 50 articles and 50,000 words for RealTime. I edited hundreds more in my capacity as proofreader and, later, online producer. No wonder I recall the theatre and performance of that decade with such clarity: they were formative years, yes, but made moreso because the experiences and memories were processed within the highly informative context of RealTime. Politically, these years coincided with the arrival of Kevin 07, the rise and fall of the Rudd-Gillard government (see my “review” of the 2010 election in RT98 Aug-Sept), and the rise and improbable rise of the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison governments. Personally, they marked the shift from student to lecturer, which is to say from performing in youth theatre (RT88, Dec 2008-Jan 2009), through reviewing youth theatre at PACT (RT100, Dec 2010-Jan 2011), Shopfront (RT105, Oct-Nov 2011), and Tantrum (RT95 Feb-March 2010, RT98 Aug Sept 2010, RT99 Oct-Nov 2010), to teaching youth about theatre at UNSW. Theatrically, the decade was associated with several trends outlined below.

Theatres of the real

One of the major trends captured in my reviews is the popularity of “theatre of the real”— Carol Martin’s broad term for the genres of autobiography, verbatim, documentary and tribunal theatre. Within the category of autobiography, I reviewed everything from Mayu Kanamori’s performance about the plight of Chika Honda (RT84 April-May 2008), Ahilan Ratnamohan’s meditations on playing professional soccer in The Football Diaries (RT91 June-July 2009), Paul Dwyer’s investigation into his surgeon father’s past in The Bougainville Photoplay Project (RT 94 Dec 2009-Jan 2010), Kim Vercoe’s “ambivalent entanglement” with Bosnia and Herzegovina in Seven Kilometres North-East (RT 100 Dec 2010-Jan 2011), and Belvoir and Big hART’s collaboration Namatjira (RT100 Dec 2010-Jan 2011).

Within the category of verbatim, I enjoyed Roslyn Oades’ Stories of Love and Hate (RT89 Feb-March 2009), later interviewing her about the practice of “headphone verbatim” (RT123 Oct-Nov 2014). If we were to stretch to the definition of verbatim, then Elevator Repair Service’s word-for-word delivery of The Sound and the Fury might count too (RT128 Aug-Sept 2015). Within the categories of documentary and tribunal theatre, I saw but rarely reviewed Version 1.0’s many works within the genre—this was mainly left to Bryoni Trezise, whose review of CMI (A Certain Maritime Incident) (RT61 June-July 2004) is still cited. I also enjoyed The Argument Sessions, based on the Supreme Court of the United States’ deliberations about marriage equality (RT128 Aug-Sept 2015). More broadly, I witnessed several works by Alicia Talbot for Urban Theatre Projects, including The Fence, which dealt with both the Stolen Generations and the Forgotten Australians, in a review I titled “Home is Where the Hurt Is” (RT 95 Feb-March 2010). I also watched several community-based projects like Minto: Live (RT 101 Feb-March 2011) and Women of Fairfield (RT Online 9 Nov 2016), led by two experts of the form: Rosie Dennis and Karen Therese respectively.

If there weren’t real people on stage, or real stories being told, then we were often in real places rather than in a theatre. I watched performance in carparks and RSL clubs, on riversides and roundabouts, in deserted shopping malls and on jam-packed buses. Tellingly, one of the final reviews I wrote deals with performance in the gallery, via three retrospectives on Yoko Ono, Joan Jonas and Mark Rothko (RT129 Oct-Nov 2015). That was a rare review for me, filed from overseas. There are only two others: one from Germany (RT82 Dec 2007-Jan 2008) and another from the Netherlands (RT104 Aug-Sept 2011). Otherwise, I attended performances in Auburn, Bankstown, Brisbane, Campbelltown, Darlinghurst, Darlington, Fairfield, Marrickville, Minto, Newcastle, Redfern, Surry Hills and Villawood. Once I even made it to the Sydney Opera House, for Back to Back’s Food Court (RT92 Aug-Sept 2009).

Theatres of ‘the refugee’

The figure of ‘the refugee’ continues to haunt the national imaginary and as a result, our stages, screens, galleries and literature. One of the first Archive Highlights I assembled was Art & Asylum: Politics, Ethics, Aesthetics in 2010 (RT Online Sept 7 2010), which gathered artistic responses to the first Pacific Solution (2001-08). It includes reviews of Urban Theatre Projects’ performances Manufacturing Dissent and Asylum, Nazar Jabour’s No Answer Yet, Mike Parr’s Malevich, Ben Ellis’s These People, Version 1.0’s CMI (A Certain Maritime Incident), the Department of Human Services’ Outside In, Towfiq Al-Qady’s Nothing But Nothing, Ros Horin’s Through the Wire, the Théâtre du Soleil’s Le dernier caravansérail, Bagryana Popov’s Subclass 26A, Kit Lazaroo’s Asylum and Mireille Astore’s installation Tampa. It also included reviews of the controversial video game Escape from Woomera as well as the films Escape for Freedom (2016), Anthem (2005), Molly and Mobarak (2003), Letters to Ali (2004), Fahimeh’s story (2004), and Lucky Miles (2007) and the SBS TV series Tales from a Suitcase, While the first Pacific Solution officially concluded in 2008, the artistic work continued. I reviewed Khoa Do’s Mother Fish twice, first as a rather cinematic play in 2008 (RT86 Aug-Sept 2006) and then as a rather theatrical film in 2010 (RT98 Aug-Sept 2010). In 2011, I reviewed three exhibitions at the University of Queensland Art Museum: Waiting for Asylum: Figures from an Archive; Collaborative Witness: Artists’ Responses to the Plight of the Asylum Seeker and Refugee, and John Young: Safety Zone against the background of SBS’s Go Back to Where You Came From (RT105 Oct-Nov 2011) as well as Ferenc Alexander Zavaros’s play Lucky (RT105 Oct-Nov 2011).

The second Pacific Solution effectively started in mid-2013, when Rudd resumed the Labor leadership and reneged on his previous promise to end offshore processing, not only reintroducing it but adding regional resettlement as well. Once again, artists felt compelled to respond. One of the earliest responses came in 2015 from Apocalypse Theatre Company through their remarkable Asylum season. The program included 29 short works, which ranged from the habitual genres of documentary and verbatim to the less familiar ones of physical theatre, comedy and a thriller (RT 126 April-May 2015). That same issue, I also reviewed the mobile performance Origin-Transit-Destination (RT126), provided an overview of the Moss, Mendez and Triggs reports (RT126), and drafted a national apology to survivors of immigration detention for when the time inevitably comes (RT126). (One of the most discombobulating things about the Rudd-Gillard government is that it delivered no fewer than three official apologies—the Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples (2008), the Apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants (2009) and the National Apology for Forced Adoptions (2013)—while pursuing policies that will necessitate another.) Later that year, I also reviewed a Sri Lankan Tamil Asylum Seeker’s Story As Performed By Australian Actors Under The Guidance Of A Sinhalese Director, which used comedy and metatheatricality to great effect (RT130 Dec 2015-Jan 2016).

Perhaps the most striking shift has been in the conversation surrounding these works, as it has moved from the politics of representation, through the ethics of participation, to the right to self-determination within an artistic project. Tanja Cañas’ blistering “10 things you need to consider if you are an artist—not of the refugee and asylum seeker community—looking to work with our community” was not published by RealTime, but I wish it had been.

The fall of ensembles, the rise of live art

One of the other trends that has unfolded over the past decade is a decline in the number of artists working in ensembles. When reading the reviews from the 1990s, I have the impression that to be a “constant spectator” in Sydney—as a profile of inveterate audience member George Papanicolaou (RT2 Aug-Sept 1994) was titled in the second edition of RealTime—was to be in constant conversation with a series of ensembles including Entr’acte, Gravity Feed, Open City, Sidetrack and The Sydney Front. I caught the tail end of this trend, witnessing one generation of ensembles—Version 1.0 and Theatre Kantanka – joined by the next—My Darling Patricia, Post, Team MESS and Applespiel. In recent years, however, my sense is that I am in conversation with fewer ensembles.

The diagnosis is difficult. The fall of the ensemble could be due to the state of arts funding, which is generally down as well as decentralised. Or, it could be due to the rise of live art and the associated rise of festivals. (Sidenote, farewell to the beloved event-based ventures Tiny Stadiums and, my personal favourite, Imperial Panda which Adam Jasper described as the “barometer of a generation” in RT90 April-May 2009 and which I delighted in, in RT102 April-May 2011.) It’s not that ensembles don’t work in live art formats; Perth’s pvi collective, for example, are masters of the form. However, the ensemble functions as an enabling structure or infrastructure rather than as a spectacle and as a result they are not visible in the same way.

One other explanation would have us dig deeper and contemplate the possibility that ensembles may have depended on a degree of cultural homogeneity. That is a polite way of saying that many ensembles were predominantly white and that as the arts have become more diverse, ensembles and their audiences have had to work harder to find common cultural and theatrical languages. Speaking of representation, one of the joys of reviewing has been documenting the work of women: those already mentioned above as well as Zoe Coombs Marr, Nicola Gunn, Mish Grigor, Victoria Hunt, Jane McKernan, Nat Randall, Talya Rubin, Lara Thoms and so many more—“Live work, women’s work,” as the title of my female-focused review of Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival had it in 2011 (RT101 Feb-March 2011).

The dearth of government arts policy

Perhaps the thing I will miss most about RealTime is its passion for critiquing arts policy. While I didn’t write any of these articles, I read them all as I became increasingly interested in the material conditions underpinning the work I saw. Together with Platform Papers, RealTime recorded a decade of policy false starts and failures. There are analyses of arts policy—or its lack—during the 2010 election (RT98 Aug-Sept), in 2011 when Labor was drafting a National Cultural Policy (RT105 Oct-Nov), and again during the 2013 election (RT116 Aug-Sept 2013). In 2014, there is a stunned response to the Abbott Government’s first budget (RT121 June-July), followed by an attempt to engage with the Five-Year Strategic Plan for a Culturally Ambitious Nation in 2014 (RT123 Oct-Nov). In 2015 and 2016, RealTime records the Brandis “Arts Heist” (RT126 April-May 2015) as well as Catalyst aka the Fifield Fund (RT Online 27 Jan 2016). There are also astute engagements with Platform Papers by Justin O’Connor (RT Online 1 June 2016) and Ben Eltham (RT Online 26 Aug 2016).

Lately, I have been missing this sort of analysis. For it is now three years since the announcement of the first round of Australia Council four-year organisational funding post-Brandis. That round had a 49 percent success rate (128 of 262 applications were funded). Since then multiple companies have folded, merged or restructured. Incredibly, the forthcoming round is expected to be even more competitive because the total amount of money available has stayed the same ($28 million per annum according to the Council’s Four Year Funding for Arts Organisations document, page 3), but the amount that companies can ask for has risen from $300,000 per annum to $500,000. To invoke the pie metaphor so beloved of economic rationalists: the government has now grown the pie, but the slices might well be bigger, and therefore the number of those sustained by it will be smaller.

When conducting information sessions in Sydney in February, Australia Council staff stated that they are expecting a success rate of around 15% for Stage 1: Expression of Interest and 80 to 85% for Stage 2: Full Applications. Elsewhere, they have been more cautious about predicting success rates, saying of Stage 1, “you can expect it to be challenging,” and of Stage 2, “we are aiming to have a success rate of somewhere around 80 to 85%.” This, in turn, is likely to result in a halving of the number of small-to-medium arts companies the Council supports via this mechanism. In other words, whereas in 2016 the Theatre panel funded 24 companies, they might now be able to support, say, 12 or 13. The Emerging and Experimental panel funded five companies and is now expecting to support approximately three. The Community and Cultural Development panel supported 15 organisations and expects to sustain eight or nine. The Multi-Arts panel supported 11 organisations but will fund possibly six this time around. Meanwhile, the Majors go untouched. The very body that is supposed to support the sector is slowly strangling it. If you live in Victoria, then Creative Victoria might pick up the pieces but if you live in NSW, where Create NSW recently ran a project round with a 2.7% success rate, the situation is increasingly desperate.

In the absence of RealTime, I had hoped that a new supportive venture, titled A New Approach, would step in but it is moving at glacial pace. The timeline is thus: in December 2016, the Myer, Keir and Fairfax Foundations called for Expressions of Interest that would “address the critical need for an informed, independent entity which has the necessary resources and public authority to advance a coherent, comprehensive policy position to help build better political and institutional settings and promote the benefits of Australia’s arts and cultural sectors as critical to our nation’s future.” In August 2017, they announced that the $1.65 million grant was going to the Australian Academy of the Humanities and Newgate Communications. Neither is noted for their arts advocacy, but hopes were still high that the combination of a learned academy and public relations firm would bring both weight and reach to the debate. In December 2017, they, in turn, announced that they had recruited Kate Fielding to lead the initiative. In April 2019, they revealed that they had assembled an advisory body to meet for the first time in May 2019.

Two-and-a-half years have elapsed since the EOI and not a single report, policy recommendation or piece of research has been released. Nor has anyone appeared on Q&A, at a writer’s festival, or even in the op-ed pages. In the meantime, several state elections (Queensland and Western Australia in 2017, SA, Tasmania and Victoria in 2018, New South Wales in 2019) and now a federal election have passed without comment or advocacy for the arts. In addition, agencies like the Australia Council have been consulting on a range of initiatives but A New Approach has stayed silent. On the highly problematic Major Performing Arts Group Framework? No public comment. The Australia Council’s new Strategic Plan 2020-24? No public comment. The consultation on a National Indigenous Arts & Cultural Authority? No public comment. This could be because the Chair of the Reference Group for A New Approach, Rupert Myer AO, was previously Chair of the Australia Council for the Arts from 2012 until mid-2018, but no public statement about this potential conflict of interest has been released.

Ordinarily, I am all for slow scholarship but the arts sector in Australia does not have this sort of time. I hope it’s worth the wait, and that A New Approach releases some ground-breaking research and policy papers shortly, but I worry that by the time they are ready, the arts might be all but gone. And it’s hard to explain just how far a resourceful arts company—or publication—could have made that $1.65 million go.

Performance futures

When contemplating the recent four-year funding round, I mused that it would be great if the publications Running Dog (Sydney), Audrey Journal (Sydney), Witness (Melbourne) and Seesaw (Perth) could apply as a consortium. None has the national reach or diversity of artform coverage of RealTime, but together they would come close. Do national conversations matter? In the wake of the most recent election, the answer can only be yes.

More than any other artform, performance pushes my thinking about what it is to assemble, to represent, to embody and to enact. Long before Roslyn Helper had announced her inspired A Government of Artists for Next Wave 2020, one had already been assembled in the pages of RealTime. I am grateful to have been a member of this parliament and to have served alongside the honourable Keith Gallasch, Virginia Baxter, Gail Priest, Felicity Clark and Katerina Sakkas.

–

Caroline Wake is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow and Lecturer in Theatre and Performance at UNSW Sydney, focusing on politics and performance, theatres of the real (documentary, verbatim and autobiographical performance), and the cultural afterlives of performance. Caroline worked for RealTime as proofreader, online producer and writer from 2007.

Read about Caroline here.

Top image credit: Executive Stress/Corporate Retreat, Applespiel, Tiny Stadiums Festival 2011, PACT, photo courtesy the artists

RealTime’s coverage of Australian contemporary dance was unprecedented. Until their first edition in 1994, the major papers mainly covered established companies and artists presented in ‘legitimate’ theatres, and Dance Australia magazine rarely veered beyond major dance organisations in preview or review. There were very few other outlets for dance criticism so that, more often than one might expect, RealTime was the only place that independent work (the largest sector in the field) was reviewed. This was recently pointed out by Branch Nebula who have depended on RealTime’s support as their only review outlet since 2008 (Brannigan, Interview with Branch Nebula Part 1). Due to the commitment of editors Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter to this breadth and depth of coverage, RealTime has been pivotal in writing the story of Australian contemporary dance since the 1990s, mapping national trends by carefully holding ephemeral works in excellent writing that speaks to us across decades. The discourse has fed the form, filling in blank spaces in the mediascape and the archive, and giving voice to artists themselves.

Following the trend that emerged from the critics imbedded in the New York experimental art scene in the second half of the 20th century, local writers responded to the work of peers and colleagues in the supportive context of RealTime where the review form’s documentation function was taken seriously. As I’ve noted elsewhere, RealTime offers readers consistent coverage of an artist, tracking their ‘moves’ over a number of years (Brannigan, Introduction: RealTime Dance).

Key fellow-writers over many years have included Jodie McNeilly, Pauline Manley, Julie-Anne Long and Philipa Rothfield—all involved in our local scenes as dance artists, dramaturgs, curators and pedagogues—writing alongside journalists, academics and freelancers like John Bailey, Maggi Phillips, Ben Brooker, Jana Perkovic, Anne Thompson, Varia Karipoff, Linda Marie Walker, Carl Nilsson-Polias, Kathryn Kelly, Jonathan Bollen, Rachel Fensham, Douglas Leonard, Sharon Boughen, Sarah Miller, Andrew Fuhrmann and Jonathan Marshall, as well as Gallasch and Baxter. Artist-writers were a part of the mix, such as Eleanor Brickhill, Zsuzsanna Soboslay, Martin del Amo, Vicki Van Hout, Nikki Heywood, Tony Osborne, Bernadette Ashley and Jane McKernan. RealTime’s commitment to developing a field of criticality for dance through numerous workshops and masterclasses has also paid off with a new generation of dance writers emerging in the 2000s, including Jessica Sabatini, and Cleo Mees.

The local activities in each Australian state and territory have also met on the pages of RealTime, a rare thing given there is no national dance festival and despite strong links between individual artists across state lines. In 2010, Sophie Travers surveyed the issue of national touring, a huge deficit that has unfortunately only worsened in the last decade (Australian Dance: Unseen at Home, RT95 Feb-March 2010). While Dance Massive as been touted as an Australian dance festival, it remains Melbourne-centric and thus hasn’t solved the problem of repertoire mobility. Andrew Fuhrmann’s review of the 2017 festival included two Melbourne artists of the four he covered, however Melbourne artists actually made up three quarters of the Dance Massive program (Experience into Dance: Translation and Failure, RT38 April-May 2017).

Byron Perry, Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Conversation Piece, Lucy Guerin Inc, 2013, photo Ponch Hawkes

Victoria

Melbourne has a reputation as the spiritual home of dance in Australia, housing the Australian Ballet and its school and the Dance Department at the Victorian College of the Arts which established the first conservatoire model dance degree in Australia, producing some of our best dancers and choreographers, alongside the Deakin University dance program which established the first Australian Dance BA focusing on Education. There is no doubt that the city has the busiest dance scene and RealTime has documented the institution of Chunky Move (1995) (Chunky Move, Wet and Bonehead, RT24, April-May 1998) and Lucy Guerin Inc (2002). Jonathan Marshall surveys Guerin’s body of work on the cusp of this change (Between Temperature and Temperament, RT52 Dec 2002-Jan 2003) as a hub of opportunity and resources for the community. Lineages flowing out of this infrastructure are recorded in reviews of the second generation choreographers such as Stephanie Lake (Marshall links her style to Phillip Adams in Stephanie Lake, RT57 Oct-Nov 2003), Antony Hamilton (Jessica Sabatini, Breaking Through the Fog of Myth, RT122 Aug-Sept 2014), Byron Perry and Jo Lloyd, whose early work was supported by Guerin (Philipa Rothfield, Lateral Moves, RT70 Dec 2005-Jan 2006), Lee Serle (see Bernadette Ashley on his The Three Dancers for Dancenorth, From Picasso to Music to Dance, R134 Aug-Sept 2016) and Luke George (Virginia Baxter matches the energy of George’s Now Now Now in her response, Present Tense, RT102 April-May 2011). Strong links with visual arts venues and post-conceptual tendencies have distinguished the Melbourne field of work and shaped the emergence of the Keir Choreographic Award, Australia’s first choreographic prize.

Victor Bramich, Lisa Griffiths, Shona Erskine, Nalina Wait, Fine Line Terrain, Sue Healey, 2004, photo Alejandro Rolandi

New South Wales

The Sydney dance scene encompasses Sydney Dance Company, Bangarra and the independents, the latter being strongly linked to Performance Space historically. Performance Space and RealTime were synonymous for me in the 1990s and early 2000s and One Extra (directors Graeme Watson, Julie-Anne Long), Dance Exchange (Russell Dumas) and Rosalind Crisp’s Omeo Studio completed the picture. As well as reviewing works made by Sue Healey, Rosalind Crisp, Shaun Parker and Martin del Amo, RealTime has since tracked the shift to a fragmented but exciting diversity of venues alongside the demise of access to the larger presenting venues in Sydney, not just for the small-scale works but our major dance companies also. (Gallasch comments on the ecological challenges in Sydney in Readymade Work’s Very Happy Hour, RT Online 1 May 2018).

After a series of Spring Dance programs (2009-2012), the Sydney Opera House closed its doors on Australian contemporary dance (except for Bangarra) until Fiona Winning’s arrival there in 2017 as Director, Programming. A modestly numbered, but highly proactive new generation of artists including Ivey Wawn, Angela Goh, Bhenji Ra, Rhiannon Newton and Amrita Hepi, have occupied galleries, clubs, and public spaces (Cleo Mees on Rhiannon’s work at Firstdraft, Dancing into Infinity, RT Online, 29 Aug 2017 and Laura McLean on Goh and Ra at the same gallery, Techno-Shapeshifting, RT Online 26 April 2017).

Beyond the inner city, Western Sydney’s FORM Dance Projects at Parramatta Riverside, Campbelltown Arts Centre and Newcastle’s Catapult Dance nurture and present important new work. See Pauline Manley’s comments on culturally sharp programming at FORM (Common Anomalies: Dancing with Difference, RT Online 21 November 2017), the editorial Growing Choreography in Newcastle (RT Online 16 Nov 2016), and my interview with then Campbelltown Arts Centre CEO Lisa Havilah and curator Emma Saunders (RT93 Oct-Nov 2009). Havilah’s collaboration with Saunders and Susan Gibb in 2009, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing, set the scene for this expansion of dance in Sydney and pioneered new curatorial directions across dance, performance and the gallery.

Western Australia

In Perth Sarah Miller’s tenure as Artistic Director at PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Art) imbedded contemporary dance in that institution’s programming. Dancers Are Space Eaters, launched in 1996, was perhaps Australia’s first contemporary dance festival (Rachel Fensham and Sarah Miller, For the Thinking Dancer, RT 11, Feb-March 1996; Grisha Dolgopolov, Who Said? RT34 Dec-Jan 1999). Miller was also a reviewer of dance for RealTime; her 2001 review (RT 37 June-July 2000) of a Paul O’Sullivan and Sue Peacock double-bill mentions other key figures of a generation: Stefan Karlsson, Olivia Millard, Sue Peacock, Sete Tele and Claudia Alessi (and I would add the important Chrissie Parrott). The Dance program at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts supports local artists with teaching and is another source of new generations of dancers and makers.

Coverage of Perth artists by Jonathan Marshall, Maggi Phillips and Nerida Dickinson saw the emergence of a new generation including Paea Leach, Aimee Smith, Laura Boynes and Olivia Millard, and the MoveMe Festival (Marshall, MoveMe Festival 2016: The Call to Dance, RT Online, 24 August 2016). Strut Dance, established in 2003 by Sue Peacock and Gabrielle Sullivan, joined Dancehouse in Melbourne and since then, Critical Path in Sydney to create a network of like-minded organisations servicing artist development.

Queensland

The Queensland scene has been diverse geographically, culturally and generically, with Dancenorth, directed by Kyle Page, touring internationally and operating from Townsville, Bonemap in Cairns and Gavin Webber and Grayson Millwood with their company, The Farm, on the Gold Coast, bringing a European style of dance theatre to the state and beyond. Dance reviewers included the late Doug Leonard, Julia Postle, Shaaron Boughen, Bernadette Ashley (responding to Dance North over many years), Rebecca Youdell and Kathryn Kelly.

In Brisbane, from the 1990s on the Suzuki Method was influential via the companies Zen Zen Zo and Frank Theatre (John Nobbs, Jacqui Carroll), as have been circus and performance. Lisa O’Neill (ex-Frank) and Brian Lucas (including his work with Expressions Dance Company) have been key players, and mentors, alongside newcomers like choreographer Lisa Wilson, while QUT dance graduates feed the local dance scene. The influence of South Pacific cultures is felt in the work of Polytoxic (Efeso Fa’anana, Leah Shelton, Lisa Fa’alafi; see Unpacking South Pacific fantasies, RT72, April-May 2006) and Indigenous culture in the works and advocacy of Marilyn Miller and BlakDance, the Brisbane-based peak body for Indigenous dance in Australia. 2017’s Supercell Festival of Contemporary Dance revealed the potential of a much-needed international dance event.

Zoe Barry, Anastasia Retallack, Safe from Harm, choreographer Ingrid Voorendt with Restless Dance, 2008, photo David Wilson

South Australia

Writers Anne Thompson, Helen Omand, Linda Marie Walker, Jonathan Bollen and more recently Ben Brooker have covered dance in Adelaide where ADT (Australian Dance Theatre) has held its ground for decades. The company entered a new phase, extensively covered by RealTime, when Sydney-based choreographer Garry Stewart took on the directorship in 1999 and engaged with, among others, scientists and media artists. Leigh Warren and Dancers has also played a key role in Adelaide’s dance ecology, including collaborations such as Philip Glass’ opera Akhnaten with the State Opera of South Australia.

A local independent scene has produced notable female dancemakers such as Astrid Pill, Katrina Lazaroff, Fleur Elise Noble, Helen Omand and Alison Currie, Ingrid Voorendt, Gabrielle Nankivell and Larissa MacGowan (the latter two ex-ADT). Restless Dance Theatre, a rare disability arts company rooted in dance, was founded in 1991 by Sally Chance who was interviewed about its origins by Anne Thompson (Enabling Dance, RT22 Dec-Jan 1997). Subsequent artistic directors have included Voorendt and Michelle Ryan.

Adelaide is also the home of the OzAsia Festival which has recently come of age with a strong dance focus, connecting local artists such as Alison Currie with peers in the region (Brooker, OzAsia 2018 Performance: More Than Cultural Diplomacy, RT 5 Dec 2018).

Tasmania

Salamanca Moves 2016 in Hobart, covered by Lucy Hawthorne, showcased the local scene alongside international acts, putting local artists into dialogue with significant internationals such as Liz Aggis (Internationals, Locals, Any Body and Every Body, RT Online 19 Oct 2016). Tasdance, Second Echo Ensemble, and MADE (Mature Artist’s Dance Experience) and, at various times, independents like Wendy Morrow and Wendy McPhee, have all kept contemporary dance humming across generations, as reviewed by Sue Moss, Judith Abell and Diana Klaosen. Tasmania is also home to youth-focused companies Stompin and DRILL. Many emerging Australian choreographers have cut their teeth in our most southern state with Tasdance and Stompin in particular.

Northern Territory

RealTime has followed Northern Territory’s community-based dance company Tracks, which consolidated under the name in 1994, the same year as RealTime’s founding (Joanna Barrkman, Tracks: New Venue, New Artists, RT57 Oct-Nov 2003). Tracks has featured strongly in many Darwin Festivals including a collaboration with Darwin-based choreographer and Larrakia man Gary Lang (Malcolm Smith, The riches of rusting RT64 December-January 2004). Lang is artistic director of NT Dance Company; Fiona Carter reviews his work Mokuy (Healing the Pain of Loss, RT121, June-July 2014).

ACT

Coverage of dance in Canberra (from 1980 to 1996 once home successively to Human Veins Dance Theatre, Meryl Tankard Company and Vis-a-Vis Dance) was largely limited to reviews of QL2 Dance and its impressive youth group Quantum Leap (Zsuzsanna Soboslay, Sharing Country, RT117 Oct-Nov 2013.

Deanne Butterworth, Kylie Walters, Jo Lloyd, Shelley Lasica’s Action Situation, 1999, photo Kate Gollings

A visual arts dance paradigm, Keir Awards & Post-Dance

The Keir Choreographic Awards were established in 2014 though a partnership between philanthropist Philip Keir and the Australia Council for the Arts. Some of the teething problems were recorded in RealTime; Keith Gallasch documents the controversy over ‘form’ that the first iteration precipitated in an article that called for a public discussion that has never happened (Was There Dancing?, R123 Oct-Nov 2014). That the judging panels have included so many visual arts specialists indicates the current liaison between dance and the visual arts, a tendency that emerged from the intermedial hotbed of Brussels in the early 1990s in the pre-‘conceptual’ work of Meg Stuart. Since then, it has been connected to a trend towards ‘non-dance’ led by primarily male French choreographers and expressed fully in Boris Charmatz’ Musée de la danse. This has resulted in many and varied experiments across disciplinary borders, including local artists such as Lizzie Thomson, Matthew Day, Brooke Stamp and Angela Goh. Shelley Lasica has occupied this terrain since the early 1990s and RealTime has covered her body of work extensively, with special attention to her work from Philipa Rothfield (see for example, A Differential Tale, RT30 April-May 1999).

Contemporary Indigenous Dance

RealTime’s coverage of contemporary Indigenous dance has consistently identified exciting new artists in the field, and recognised the achievements of established ones. The editors’ support of artists such as Vicki Van Hout has done much to encourage and disseminate their work, as was recently recounted by the artist (Brannigan, Interview with Vicki Van Hout, Part 1) Keith Gallasch’s reviews of Van Hout’s work are exemplars of the role that the reviewer can take in bringing to light new artists and uncovering their innovations (Brilliance, Shimmer, and Shine, RT103 June-July 2011). Van Hout has gone on to write pieces for RealTime and her blog for FORM, providing an important Indigenous voice on dance, including her musings on an issue close to her heart: the tensions between Indigenous cultural protocols and innovative arts practices (Burning Issue—Authenticity: heritage and avant-garde, RT111 Oct-Nov 2012).

Torres Strait Islander Ghenoa Gela, winner of the 2nd Keir Choreographic Award in 2016, was reviewed by Andrew Fuhrmann who saw promise in the artist amongst stiff competition, and an investment by Keir in choreographers exploring non-Western cultural forms was continued with the excellent Javanese-Australian choreographer Melanie Lane taking the award in 2018. Broome-based Dalisa Pigram, co-artistic director of Marrugeku with Rachael Swain, has also been followed closely in RealTime (video interview by Gail Priest, We Can All Dream, RT125, Feb-March 2015). The magazine has also covered high profile artists such as Stephen Page and is Bangarra Dance Theatre artists Patrick Thaiday and Elma Kris. (RealTime mentored young Indigenous writer Rianna Tatana through her interview with Kris, Elma Kris: From a Torres Strait Islander Perspective, RT124 Dec 2014-Jan 2015.)

2000s and screen dance

I think my first article for RealTime was written in 1997 on the Microdance series of shorts made for ABC TV. RealTime already loomed large as my window onto the experimental arts in Sydney, Australia and the world. I transferred information in their advertisements into my diary diligently, and followed the careers of dance artists through the thick descriptions encouraged by a nebulous ‘house style’ that privileged careful accounts over reductive judgments. In RealTime I also found somewhere open to publishing articles emerging from my burgeoning interest in intermedial practices across dance and film/video. The magazine maintained a commitment to covering this niche field of practice, commissioning myself and writers overseas to cover the international field, supporting events closer to home through smart critique, and running a workshop for aspiring writers alongside the 2008 edition of ReelDance International Dance Screen Festival in Sydney (RT85 June-July 2008).

Interest from Australian funding bodies in the dance-screen nexus waned after the first decade of the 21st century, and the international scene slowed down as artists across the world seemed to shift away from this expensive mode of choreographic production that requires serious resources. The most recent coverage was of Samaya Wives’ (Pippa Samaya and Tara Jade Samaya) The Knowledge Between Us (2017), which won the Australian Dance Award for the awkwardly named Dance on Film or New Media prize (Gallasch, Samaya Wives: One-Minute Dance Award Winner, RT Online, 26 Sept 2017). Young artists do seem to be returning to the form, and there has been renewed talk of screenings at ADT in Adelaide and Lucy Guerin Inc in Melbourne.

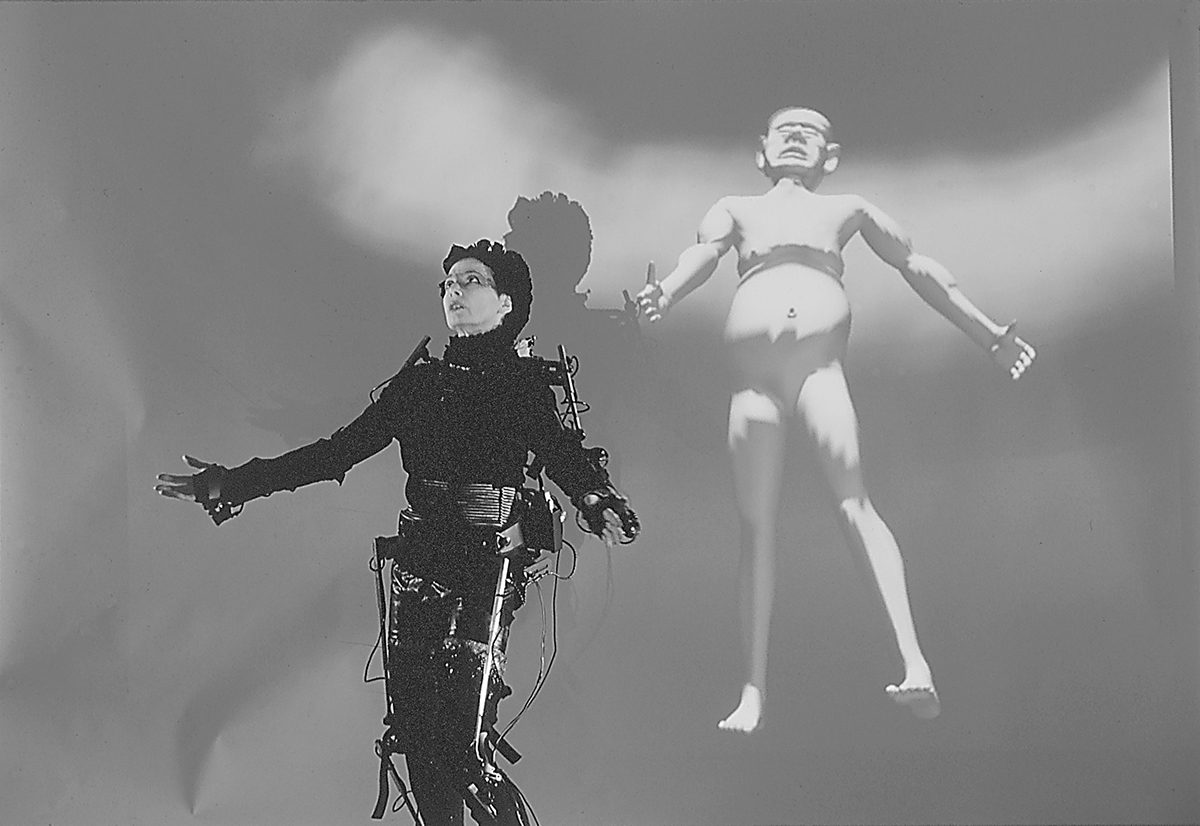

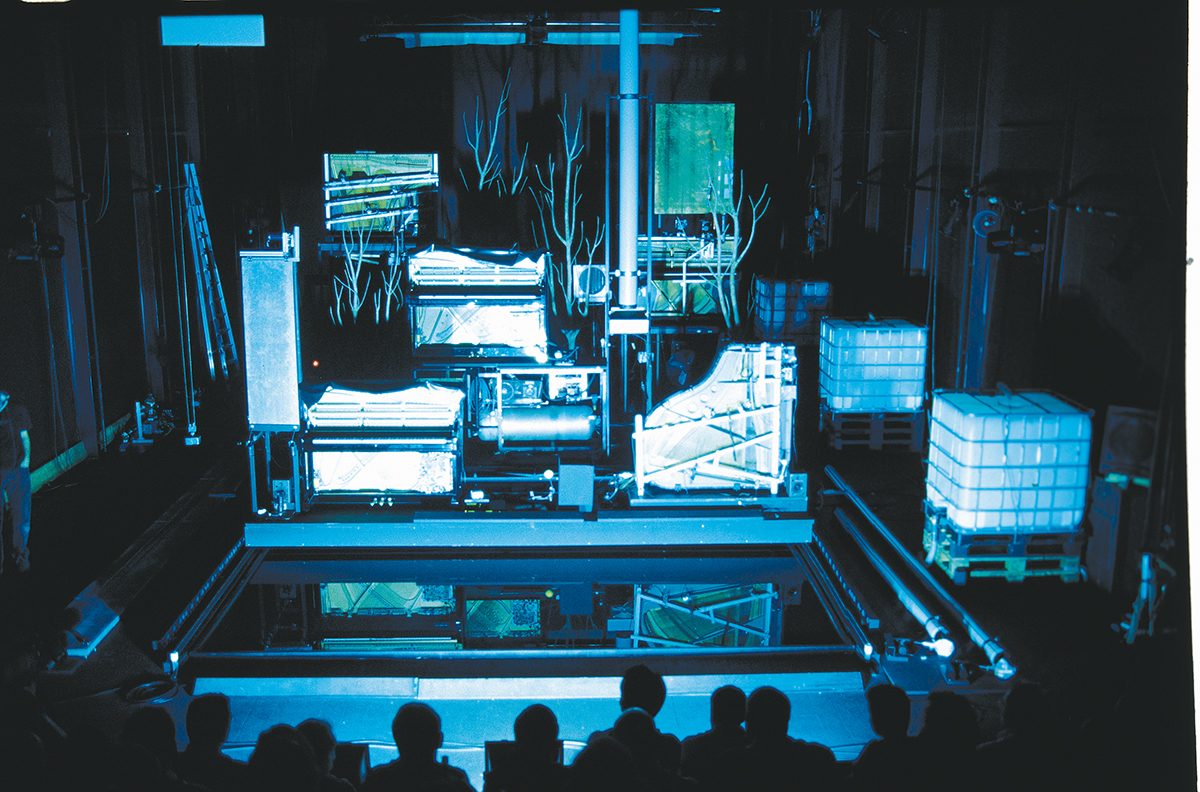

Dance and new media technologies

The investment of funding bodies in the dance-technology interface resulted in a flurry of activity across the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s. Leaders in this field have been Company in Space (Hellen Sky and John McCormick) and Margie Medlin. Medlin joined temporary Australian resident Gina Czarnecki in scoring the prestigious Sciart award from the UK’s Wellcome Trust for her work Quartet (Brannigan, Music Makes Moves, RT 76 Dec 2006-Jan 2007).

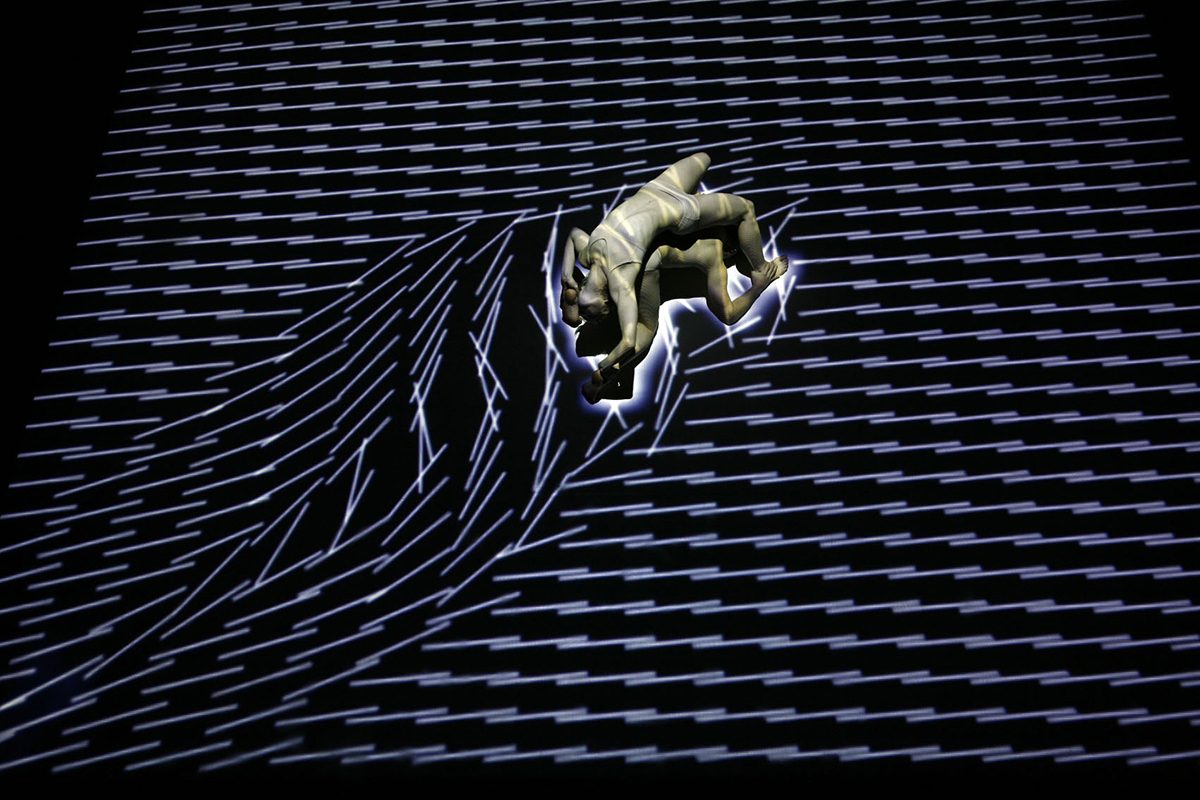

RealTime traced the development of the sub-field, and one of the most positive reviews was Gallasch’s snappy response to Gideon Obarzanek’s simple and moving Glow (Doubly Emergent: Chunky Move’s Glow at The Studio, RT78 April-May 2007). He writes: “The emergent art tool is at one with the dancer’s body in an account of an emergent organism, a huddled inhuman shape inching across the screen-floor.” In her role as Director of Critical Path, Margie Medlin championed this work. Her SEAM conference of 2010, sub-titled Agency and Action (the series running 2009-2014), was a singular event combining a new media performance program with a rigorous conference (Rackham, Mind, Play, Empathy and Machines, RT100 Dec 2010-Jan 2011).

Other publications

The booklet In Repertoire: A Guide to Australian Contemporary Dance (RealTime for the Australia Council, 1999, revised 2003) and the book Bodies of Thought: 12 Australian Choreographers (Ed. Erin Brannigan and Virginia Baxter, Wakefield Press-RealTime, 2014) are publications that draw on the magazine’s dance content as consolidated in RealTime Dance, an online resource established in 2014. In Repertoire is an Australia Council-commissioned snapshot of Australian choreographic works ready to tour in 2003. In RealTime Dance, Dance File lists Australian artists and companies alphabetically, with links to relevant RealTime articles as well as a considerable catalogue of international artists and companies.

Bodies of Thought is the first publication to bring works of key Australian choreographers together to map common approaches and themes nationally, combining interviews with critical essays supported by the RealTime archive. In this case, RealTime reviews are supplemented online with external reviews, putting RealTime into critical dialogue with other reviewing outlets. Added to this is RealTime TV which features interviews with Lee Serle, Anouk van Dijk, Dalisa Pigram, Tim Darbyshire and many others, and Dance on Screen which brings together writing on this genre.

Conclusion

Even with a most optimistic view onto the new era of democratised, online arts reviewing, it is hard to imagine another publication that could put contemporary dance into dialogue with the other arts in the same way RealTime has done. RealTime seemed to understand the leading role dance has taken, quietly and persistently, on numerous fronts; in innovating the review format, engaging with other media in an inclusive choreography with whatever materials were necessary, and the modelling of community practices so integral to the art form. The strength of the magazine in following the art form in its interdisciplinary adventures is dependent upon an editorial scope that takes it all in. For this reason RealTime’s editors Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter, and their vision for a publication where dance took centre stage, will be sorely missed by Australian dance artists and aficionados alike.

–

Erin Brannigan has written for RealTime since 1997, was the founding Director of ReelDance (1999-2008), has curated dance screen programs and exhibitions for international festivals, programmed and commissioned works for installation exhibitions and led Choreography and the Gallery: A One-Day Salon (Biennale of Sydney 2016, Art Gallery of NSW and UNSW). Erin is a Senior Lecturer in Theatre and Performance Studies at UNSW.

Top image credit: Be Your Self, Australian Dance Theatre, photo Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions