December 2019

In this edition, a focus on anxiety. At worse, it’s the kind triggered by a dictatorial Australian Government’s sudden erasure of the Arts from the title of a new mega-department (see below). At best it’s in the form of The Big Anxiety. It’s a bold, even risky title for a festival that “brings together artists, scientists and communities to question and re-imagine the state of mental health in the 21st century” (website). But far from inducing anxiety, the recent UNSW event is liberating, bringing to bear new thinking, strategies and technologies with which to address trauma, depression, panic and pain across a broad spectrum of physical, mental and cultural conditions, not least in the event’s The Empathy Clinic (image above). Curation by Jill Bennett and Bec Dean is superb, as is the spacious yet intimate exhibition design by Anna Tregloan. Focusing on r e a and Judy Atkinson’s listen_UP, Eugenie Lee’s Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery and a selection of other challenging creations, Keith recounts his experience of immersive artworks that test preconceptions, heighten the senses and expand the capacity for empathy, often in works made by sufferers themselves. Also in this edition, Ensemble Offspring supports bold new Australian compositions with inventive staging, and Branch Nebula brings spectacle to public space with DEMO.

Very big anxiety. With Stalinist verve, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has disappeared the Arts, calculatedly refusing to name them as part of the new Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications; instead they are buried in the latter portfolio. This is perfectly in sync with secret trials, a secret Senate deal over Medevac, increasingly limited Freedom of Information access and suppression of unions and a free press. A government that cannot say to the world, proudly, we have a Ministry of the Arts, is in denial of art, possibly in fear of it. Let your anger be heard. Have a safe and happy holiday season. Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: Entrance to The Empathy Clinic, The Big Anxiety, design by Anna Tregloan, photo Jessica Maurer

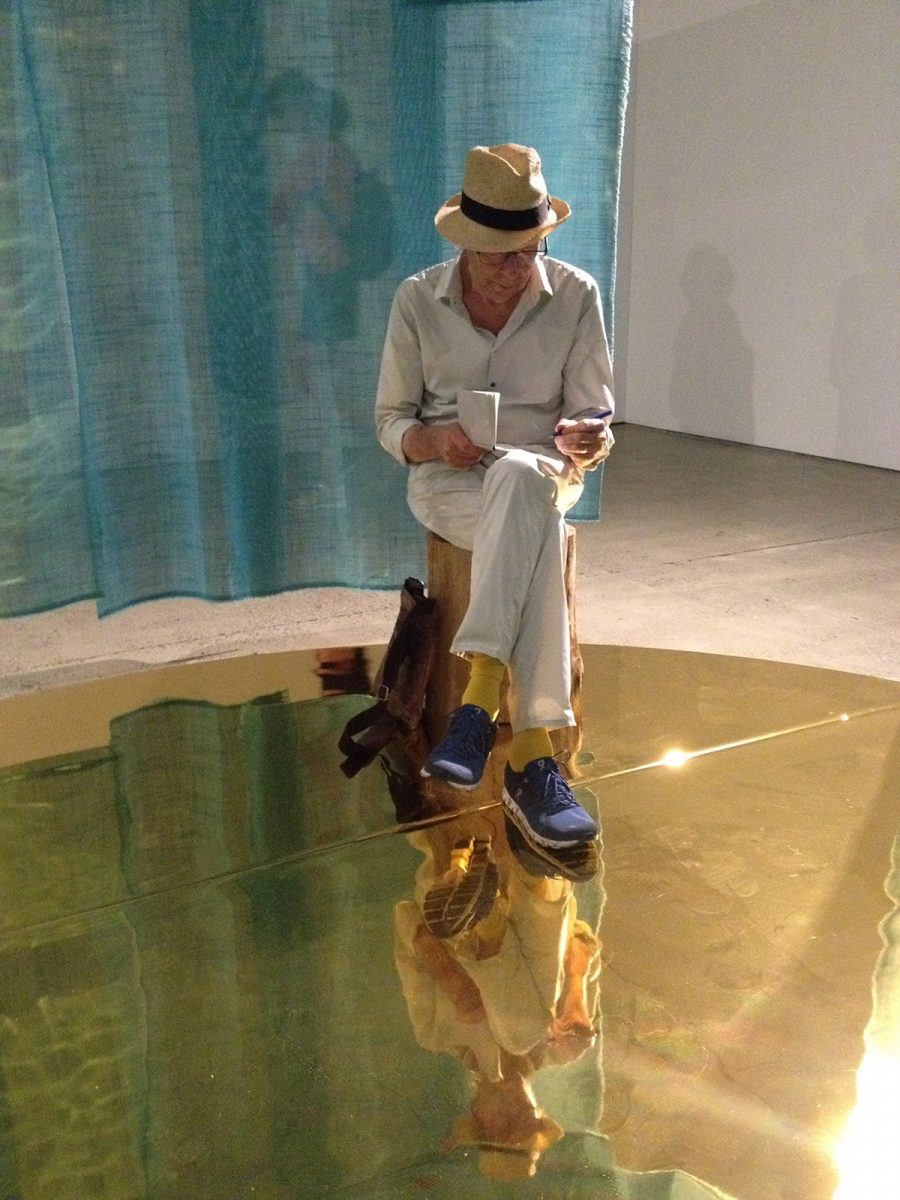

On a reflective golden floor, six tree stumps for sitting. Above, six small boat-like objects crafted from paperbark float serenely. A soft, blue cloth curtain gently encloses the intimate, circular space. The floor dips deep beneath the sitter, mirroring all that is above in the contemplative space that is listen_UP, an installation in The Big Anxiety’s Empathy Clinic. The work advocates and induces deep listening with which to understand the anger and underlying grieving born of serial trauma suffered by generations of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. As a soft crackling suggests a gentle fire at listen_UP’s centre, a very present, lone female voice, pondering inherited and personally experienced suffering, is textured with heartbeat, the rumble of restless weather and a singer expressively uttering a mutating syllable sequence emotionally in tandem with the speaker’s narrative in a sound world of gently shifting perspectives.

The speaker struggles to begin—“I am… I am…”—but the words come—“I am without hope, without future”—revealing “a pain so deep, shame of what I am, what you have made me.” She is “a child unloved,” who has introjected her oppression: “I knew that I deserved not to be loved.” She briefly proffers an explanation for white listeners’ inability to empathise: “You cannot see me… because I mirror your pain.” While her plight is existential—“To be nothing would be preferable to being”—she is compassionate for children “raped in welfare, in a world where multinationals trade in weapons.” Unable to wait for revolution, she declares she will start with herself. The singer intones “reya, reya…”

Suddenly there’s particularity, the speaker revealing her profession, declaring “university a prison without walls.” As an academic, “I build walls of paper to bury my grieving soul while children are dying.” These children are close by, “crying down the street.”

However, a sense of purpose emerges with metaphor enriching the sense of passion inherent in the quietly controlled voice: “I am fire… I am stinging nettle.” “Will you accept the need for this pain?” she asks the listener. “Illy, illy,” sings the singer. Moving beyond metaphor, doubtless drawing on her spiritual heritage, the speaker declares herself owl, spider and “goanna full of healing.” Perhaps we can now travel with her: “I hear so many songs, I will wait for you.”

Finally, the speaker, no longer “I” but “we,” celebrates “the bliss of being completely a woman” through, she says, women’s shared words, dance and song. The singer’s “eeya, eeya…” becomes “eeya, eeya, num, num…” conveying a sense of both completion and eternal duration. I have no idea what these syllables (loosely transcribed here) mean, if anything literal, but the beauty of the intensifying ritual framing they offer lends choral power to the speaker’s path from anger and despair to survival through art, amid resonating wind, thunder and rain, distant bird call and the rattling of cicadas.

The speaker is much admired Emeritus Professor Judy Atkinson AM, a Jiman/Bundjalung woman of also Anglo-Celtic and German heritage. She is the author of Trauma Trails—Recreating Songlines (Spinifex Press, 2003): The transgenerational effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia, and founder of We Ali-li, a Culturally Informed Trauma Integrated Healing training organisation.

The pioneering visual and media artist r e a has worked with Atkinson “to create an aural campfire—a place where stories are shared, listened to, understood and then reflected or meditated on. In culture the campfire is a creative learning and teaching space where elders pass on their knowledge and stories to listeners young and old” (program note). To focus and intensify this listening r e a has textured Atkinson’s voice with the artistry of Nardi Simpson (composer and singer with Stiff Gins), Missi Mel Pesa (audio-visual artist, musician and composer) and Andrew Belletty (self-described “vibro-tactile sound artist”).

Andrew Belletty kindly spoke with me about listen_UP’s embracingly natural sound design: the six small directional speakers encased in paperbark, keeping the technology invisible; the “grounding campfire” centre speaker; the two gently enveloping sub-bass speakers outside the circle; occasional sounds—birds, insects—including those from field trip recording in r e a’s country; and a realised desire to have the listener feel intimately and directly addressed by Atkinson, mouth to ear.

Listen_UP is a generous invitation to sense, via a contemplative space (exhibition designer Anna Tregloan) and aural magic, how Australia’s Indigenous peoples, as a young We Ali-li participant has put it, “we use our anger, we recycle it, we use it as power for us… to make beautiful things out of your anger, out of your hate, out of your sadness” (We Ali-li website).

–

The Big Anxiety, first staged in 2017, is a festival that “brings together artists, scientists and communities to question and re-imagine the state of mental health in the 21st century” (website). Artistic and Executive Director Professor Jill Bennett (UNSW), Producer Tanja Farman, Senior Curator Bec Dean.

The Big Anxiety: r e a and Judy Atkinson: The Empathy Clinic, listen_UP, artists r e a, Nardi Simpson, Missi Mel Pesa, Andrew Belletty; UNSW Galleries, Sydney, 23 Sept-9 Nov

Top image credit: Installation, Listen_UP, r e a and Judy Atkinson, The Big Anxiety, photo Jessica Maurer

Two brute skateboard ramps dip face to face in the forecourt of Circular Quay’s elegant, mid-Victorian Customs House. Dimly visible beneath the slipways, squirming figures slither into harsh sunlight like emergent life-forms. Two merge organically with their boards, one with his BMX-bike. Three more emerge, one of them, entwined in black concertina-ish plastic tubing which she vigorously sheds, joins another as fellow dancer while the third is a parkour traceur. They learn quickly to athletically and aesthetically duck and weave between and beneath the increasingly dangerous speedsters, who fly high and swoop like predators to Lucy Cliché’s pulsing electronica.

Once individual skills, male and female, have vigorously displayed genetic advantage, it’s time for emergent mutualism—paired flight high above the ramps for those on wheels, while the movers catch rides, share risk and celebrate collaboration with proud, cheesy tableaux straight out of circus. Suddenly, pink smoke pours apocalyptically from the BMX (scarily apt on a bushfire haze-filled Sydney day), the soundtrack roars and this seemingly robust world collapses. But out of stillness and silence, life resiliently returns in a series of virtuosic turns. At half an hour, DEMO is a brisk, cheerful, frequently thrilling parable of hope realised—with the most basic of technologies—by young bodies with trust in their collective strength.

–

City of Sydney: Branch Nebula, DEMO, co-directors Lee Wilson, Mirabelle Wouters; performer-devisors: dancers Marnie Palomares, Kathryn Puie, skater Sam Renwick, Aimee Massie, BMX Brock Horneman, parkour Antek Marciniec, composer Lucy Cliché, producer Intimate Spectacle (Harley Stumm); Customs House Square, Sydney, 30 Oct-3 Nov

Top image credit: DEMO, Branch Nebula, photo Mark Metcalfe

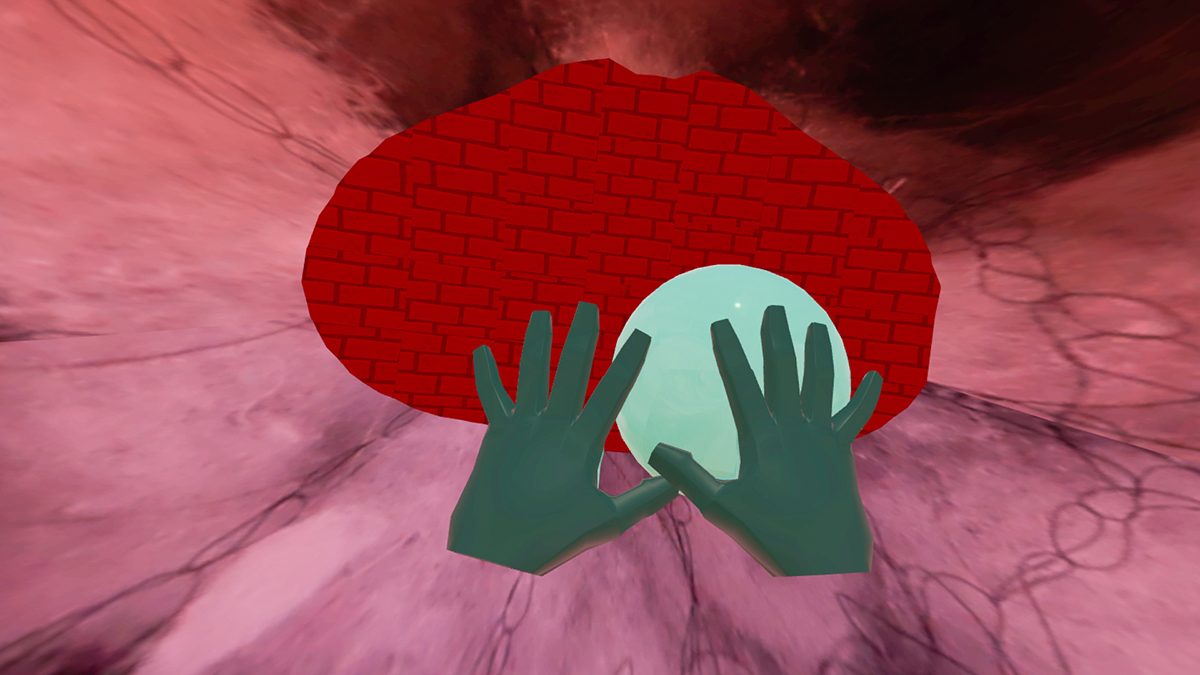

In front of me, a red brick wall. Nearer, hovers a large green ball. I hit it. It flies to the wall, knocking out a single brick and bounces back. I hit again. Another brick goes down. But the return is too fast, the ball flies past and I experience a sudden high frequency pulsing in the groin, not exactly painful, but certainly uncomfortable and even moreso each time I miss the ball and the vibrations escalate. I endure for only a few minutes (10 is the maximum), doubling up as what now feels like pain (the ‘cramping’ and ‘hammering’ sensations reported by pelvic pain patients) triggers body memory associated with hernia and prostate operations. The wall and the ball are components of an interactive animation inspired by the Breakout video game. I’m wearing a VR headset and, around my pelvis, a pumped-up inflatable belt holding two nodes to the lower abdomen. I’m spared simulated back pain because, on my visit, the tech is playing up. A blessing.

The work is Eugenie Lee’s Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery, part of The Big Anxiety’s The Empathy Clinic at UNSW Galleries. It’s an artistic creation rooted in solid multidisciplinary science exploring the experience, understanding and communication of chronic pain. Lee’s earlier works focused on externalising and objectifying it, crafting material metaphors with which to manage her own suffering. Now she offers others the opportunity to experience simulacra of chronic pain. At the first Big Anxiety in 2017, I experienced Lee’s Seeing is believing, a VR work conducted within in a padded anechoic chamber. I found myself suspended in a red void with an intensifying, grating soundscape, a barbed wire coil slowly descending around me and finally a large nail passing through the palm of my hand (wired for low-key vibration and heat). A subsequent conversation with the artist, as part of the work, involved putting the unnerving experience into words. The new work has none of the Gothic horror aesthetic of its predecessor, instead the participant is active, attempting to physically and mentally function in a simple physical-virtual game scenario while suffering ongoing and escalating bodily discomfort.

Breakout… is designed to help doctors, nurses and other health and related professionals to understand the nature and impacts of chronic pain: it’s an empathy training machine addressing the suffering regularly experienced by 20% of Australian women and possibly 8% of men. Lee’s collaborators are multidisciplinary, addressing the whole person: Dr Susan Evans (physician, pelvic pain specialist), Emeritus Professor Roland Sussex (linguist, University of Queensland), Dr Claire Ashton-James (social psychologist, empathy expert, University of Sydney), Peter de Jersey (mechatronic engineer), Warren Armstrong (VR media artist) and Big Anxiety producer Bec Dean. Lee has been aided by data from a scientific survey by Sussex, Evans and Ellie Schofield titled The Language of Pelvic Pain, produced by the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia.

Empathy: art & transfer of learning

We humans are innately empathetic—without fundamental mutualism, for example, our species would have been short-lived—but for the most part within highly determined cultural boundaries. It is often assumed that education and art in particular loosen those limits by nurturing understanding of others’ emotions and cultures. In recent years, there’s been a preoccupation with the virtues of storytelling, backed by data and theorising of various kinds, but short on an understanding of the transfer of learning required to convert empathy into application, let alone any acknowledgment of the devious narratives inflicted on us every day. The arts can arouse our sympathies, but to what extent? Nigerian-American novelist and essayist Teju Cole, while applauding the risks taken by many of his writer peers, believes only that “literature can save a life. Just one life at a time.” He writes, “After observing the foreign policies of the so-called developed countries, I cannot trust any complacent claims about the power of literature to inspire empathy. Sometimes, even, it seems that the more libraries we have over here, the more likely we are to bomb people over there.”

In her essay “The Banality of Empathy” Zambian writer Namwali Serpell also acknowledges literature’s limits: “Narrative art is indeed an incredible vehicle for virtual experience—we think and feel with characters. It simulates empathy, so we believe it stimulates it.”

Citing Paul Bloom’s complexly argued Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (Bodley Head, 2016) in which the author argues for cognitive empathy (“understanding what’s happening in other minds and bodies”) over emotional empathy (“trying to feel like or even as someone else”), Serpell writes supportively, “Bloom shows that emotional empathy is often beside the point for moral action. You don’t have to feel the suffocation, the clutch of a throat gasping for air, to save someone [from drowning].” And, as Bloom argues, too much empathy may inhibit a doctor from taking radical action which will induce pain in order to save life.

However, this either-or argument would eliminate Lee’s and a growing number of projects like those encountered in The Empathy Clinic. Surely a synthesis of ‘understanding’ and ‘feeling like’ would be an ideal goal. Pain is intensely private but we constantly share what it is like, comparing another’s with our own experience. The notion that cognitive empathy is somehow free of the traps of emotion seems untenable.

The semantics of pain

One way of coming to understand others’ pain is through attentive listening to the vocabulary and narratives with which sufferers attempt to describe (to themselves, friends, doctors) and take some control of their condition. It’s long been recognised that using metaphor is the commonest means of describing pain (transferring associations from one domain to another). Susan Sontag invaluably challenged the use of metaphor in Illness as Metaphor (1978) for its reduction of the sufferer to Other (clinically and socially objectified in terms of their illness) and the deployment of emotionally negative analogies, especially stigmatising ones to do with cancer. To achieve this, she deployed numerous metaphors herself while, critics argued, denying those in pain the same means of managing it (see Richard Gwyn, Communicating Health and Illness, Sage Publications, 2002, an excellent account of professional medical and patient metaphors and narratives).

For Lee’s Seeing is Believing, psychologist Ronald Melzack’s McGill Pain Questionnaire (1975), which mapped sensory, affective, evaluative and other descriptors used by patients to describe their experience of pain, was a touchstone. However, in Australia Professor Roland Sussex and associates have freshly researched this terrain, surveying over 1000 women about pelvic pain in The Language of Pelvic Pain study, focussing, as Sussex says in a talk, “on the guts of the language itself.” The team discovered, surprisingly, he says, that conjunctive simile usage (eg “a stabbing pain that feels like a hot barb”) was the prevalent means of description.

The researchers also learned that certain sets of similes complemented specific pelvic conditions, be they period, endometrial, ovulation, bladder or vulval pain, the latter, for example, having no “cramping” descriptors common to the other categories, let alone being the most difficult to describe. It was this new study that Lee turned to formulate the kind of discomfort she would induce in her subjects.

The sharability of pain

In her classic work The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (OUP, 1986), Elaine Scarry wrote of the existential “unsharability” of pain and its resistance to language, if not necessarily to art. Pain itself cannot be shared, but the McGill Questionnaire and The Language of Pelvic Pain project point to the capacity of sufferers to use metaphor and simile as a means of sharing expression of their pain and to have their need to be heard acknowledged. It crucially underlines commonalities of experience between sufferers. For health professionals attentive to language this sharing provides indicators of the whereabouts and nature of certain conditions and the qualities of the pain, yielding a rational understanding, Bloom’s ‘cognitive empathy.’ But metaphor is potent; it’s only a short step to the listener drawing on their own experiences of pain to becoming ‘as if’ the sufferer, just as we can have a visceral response to hearing about bodily damage or seeing operation scenes on screen. We can move quickly from understanding to emotional empathy with little or no conscious effort, but to what degree comprehended and how enduring?

Metaphor, magic & science

With her VR translation of sufferers’ metaphors into very convincing simulacra of pain for non-sufferers of pelvic pain, Eugenie Lee synthesises rational understanding and affective experience, most tellingly for me when I attempted to describe what I felt, for a moment completing a loop between myself and those whose suffering prompted the making of Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery. In a video accessible on Lee’s website, gynaecologists testing Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery, speak enthusiastically of the value of the VR’s enabling them to feel something akin to their patients’ suffering.

Like a metaphor, Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery, stands in for and expresses Eugenie Lee’s own experience of pelvic pain as well as for the women who contributed their own metaphors to The Language of Pelvic Language project. Lee’s art is informed and driven by multidisciplinary science. For much of the 20th century, positivist science saw metaphor as being loosely associative, subversive even and having no cognitive value; only literal language would do. The “sorcery” of the work’s title evokes Lee as VR conjurer of ‘pain’ and effector of balm, and a cheeky promulgator of a productive, magical tension between art and science, encouraging a potent dialectic of emotional and cognitive empathies. With further testing and collection of responses from participants, this work-in-progress seems, from my relatively innocent vantage, very promising. As Lee is aware, Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery not will not suit everyone; for some it will seem invasive. But for those happy to brave temporary physical or cultural discomfort it might be a venture into newly found or deeper empathy.

–

The Big Anxiety, first staged in 2017, is a festival that “brings together artists, scientists and communities to question and re-imagine the state of mental health in the 21st century” (website). Artistic and Executive Director Professor Jill Bennett (UNSW), Producer Tanja Farman, Senior Curator Bec Dean.

Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery, artist Eugenie Lee, physician, pelvic pain specialist Dr Susan Evans, linguist Emeritus Professor Roland Sussex, social psychologist, empathy expert Dr Claire Ashton-James, mechatronic engineer Peter de Jersey, VR media artist Warren Armstrong, producer Bec Dean; The Big Anxiety, The Empathy Clinic, UNSW Galleries, Sydney, 23 Sept-9 Nov

Top image credit: Eugenie Lee and Keith Gallasch, Breakout My Pelvic Sorcery, photo © Cynthia Sciberras