June 2021

This is a review that started out as a brief response, but its subject matter felt too important to treat lightly, a risk that Narcifixion itself takes as a stylishly propulsive entertainment with a simple message – in effect, ‘beware screen-driven narcissism, it’ll destroy you.’ I found myself wanting to honour the makers by detailing the logic, as I see it, of the work’s construction and the nature of its vision.

Mashing “narcissism” with “crucifixion” for his title, choreographer-director Anton readies his audience for Narcifixion’s account of self-crucifying self-possession. It’s a common belief that we’re living in an era of rampant narcissism brought on by the unfortunate co-emergence of me-first neoliberal capitalism and social media platforms. On the other hand, narcissism is a necessary and highly complex component of psychological development and survival, manifesting in many ways, good and bad and, in extremis, a serious affliction.

I wonder, therefore, where ‘on the narcissism spectrum’ each of us sits: from apparent zero in some to the uneasy balancing of self and other in many of us, to the deceptive cover that is passive aggression, to the “controllers,” to narcissism’s full-blown realisation in attention seeking, power grabbing egotism driven by fear, conscious or not, of utter inadequacy? What will Narcifixion tell me?

Sorry to miss the performance in-theatre, I nonetheless had the advantage of watching a live stream of the final performance as well as a subsequent re-viewing. Save for distant images of a very wide stage, the work on screen was delivered with a finely lit and shot intimacy highly apt for the subject and for observing the precision and dynamism of the dancing.

NARCIFIXION AT WORK

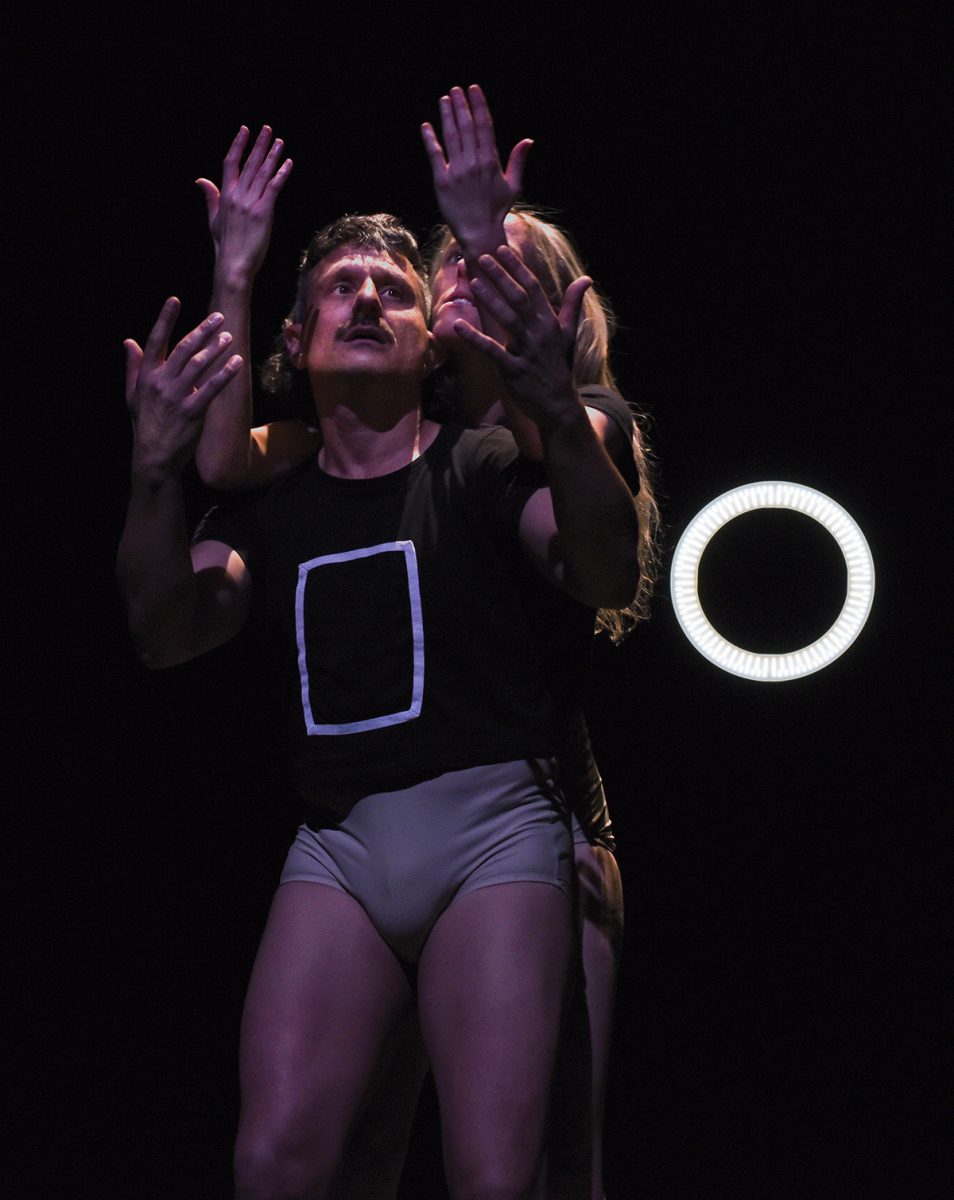

From darkness, green warning beacons signal furiously, their agents barely invisible. From silence, one voice and then two intone ‘me’ in an impassioned string of distorting variations against a sustained grainy drone that soars into Vangelis-Blade Runner organ-synth that says sci-fi, confirmed with a flood of blue light revealing the two signallers (Anton, Brianna Kell) beneath an ominously pulsing electronic eye that presumably surveils them. Identically uniformed in flexible plastic tops and glass-visored helmets, the pair move in neat synch, the flow now and then interrupted by seeming mechanical faltering. Something is not right with these perhaps less than human beings, cyborgs maybe, and presumably the narcissists implied by the work’s title.

They soon appear real enough. To a trumpeting fanfare and bathed in red light, they formally remove their helmets and wrap-around shades, briefly mirror each other with smiles, muscular posturing and outstretched fingers that agonisingly strain to touch the other. Failure results in jerky agitation. Peeling off their tops (like swaying, skin-shedding snakes), they are even further freed of the outward shell of purpose but, curiously, sink to the floor.

Immobilised, face-down they gradually revive in an elegant micro dance of fingers, new life that quite gradually extends to arms, to bodies sitting, swivelling, to bodies, unfortunately, on backs like upturned insects racked by passing tremors. The further the pair is removed from the protective anonymity of uniform, of routine, the more naked they are, the worse their condition — narcissists short of the fuel provided by admirers?

Seemingly half-conscious, the couple rise. Ambiguous poses (some heroic, some like beach fashion modelling) slip into supple movements, increasingly one-hand-led, and escalating manically — replete with indeterminate signalling and sporadic jerkiness — until pulled to a halt. They peer serenely into the palms of their raised hands as if into unseen mirrors, and then, in a gentle turn and sway, hands lowered, look down on them as if gazing into water like the Narcissus of myth.

The selfish pleasure of narcissism demands constant refuelling; if not met anxiety ensues. With shocking suddenness, the pair’s hands turn on them, striking, pulling, spinning, vibrating them, until two becomes one, a four-armed, strobed, panicked creature fixated on mirror-palms that yield no sustaining sense of self. Exhausted and entangled, body against body, in a slow circular walk the pair refuse eye contact and touching comes to nothing in a sad little disengagement.

A new phase ensues, one of individual endeavours. He tries to communicate with her. First, it’s casual, a smile, an ‘Aaaah,’ then an indecipherable deep-throated utterance, then a cocky little circular dance — an invitation? The display grows grotesque, his t-shirt pulled up, a cartwheel, high kicks, failure to connect, a tantrum — narcissistic rage. Exhaustion.

It’s her turn. She carries a silvery, transparent plastic sheet the height and width of her body. It mirrors her gaze and movement in a slow, intimate dance between self and an image inviting curiosity and attraction, but then fixes stiflingly to her. The dark clattering of the amplified material is claustrophobic. There and not there, she is eventually nothing more than a fading image. Her mirror dance a narcissistic dead-end: a mere image cannot sustain self.

Another attempt to secure that self is announced with a darkly underscored, cicada-like beat. Standing before the ‘eye’ each neatens their hair, checks the other’s face, and together step into a spot-lit space, suddenly aware of an audience. Like fashion models they venture into a rehearsal of stylish strutting and then loping across the stage, hyper-smiling, pulling off t-shirts (branded with a square version of the ‘eye’) and settling into a ludicrous show girl promenade and, as the music dips away, embarrassingly exhaling overt groans of pleasure and self-congratulation, climaxing in an ‘Aaah!’ of joint approval, heads exultantly thrown back.

Such rare if empty success, free of now anticipated breakdown, prompts more exaggerated exertion, with a growing sense of omnipotence. A dark drum beat glides deep into a throbbing pulse introducing a protracted, bigger than life, hyper-articulated disco sequence that progresses with supreme confidence, faultless synchrony and increasingly expansive moves, dance as pure narcissistic display, with none of disco’s double offering of individual interiority and crowd communality.

The hand as mirror motif makes a brief appearance, integrated into the dance, before the desire to break out of the single self, to once more touch, recurs exactly as it first did, bodies awkwardly angled towards each other, fingers fluttering in near connection, stilled bodies helplessly vibrating. The pair break out, walking then dancing into proud recovery. But this too is doomed. They wind down, depleted, the world darkening around them, hands outstretched but palms now turned down, reaching out as if blindly into nothingness as a haunting oceanic swirling thins out into silence.

WORRYING AT NARCIFIXION

It’s a grim ending, this in-effect blinding, a cruel fate for a pair fixated on sight, on the gaze received from their mirror selves and imagined admirers. Are we complicit in this cruelty? While we’ve scrutinised and laughed at the pair’s self-crucifying behaviour, there is no way out for them in this scenario, or for ourselves.

Anton writes, “This union of words (Narcifixion) is a warning against getting too caught up in your ‘virtual’ identity.” But is this sufficient? If narcissism is a closed circuit, so is Anton’s critique of it, a vivid, exacting portrayal of a compulsive condition and its escalating pathology as the pair seek out new ways to reach impossible fulfilment, but throughout within that closed loop of grandiose effort and abject failure. What if one of the pair were eventually ‘unplugged’ instead of doomed? Which points to one of the stranger dimensions of the work, the absence of a dynamic between the two figures.

Anton describes Narcifixion as “a dance for two singular characters caught in a constant state of exhibiting and observing themselves.” Just how ‘singular’? Except for the conventional gender distribution of the two solos (the male as extrovert mate-seeker; the female locked in her mirror gaze), these narcissists are otherwise undifferentiated, save in appearance, dancing in exacting tight-knit harmony, in a duet of sameness without opposition or counterpoint (might one narcissist sooner or later strive to outcompete or demolish the other?). Is then the narcissism of our era exactly the same for one or two or three or more of us?

This absence of differentiation underlines the unresolved hybridity of a work that looks like dance theatre (the elaborate sci-fi-ish set-up of the opening, not returned to, the intensifying pattern of release and breakdown, the contrasting solos that have no other ramification) but inclines to a series of lightly themed, abstracted states of being, a relentless dancing for dance’s sake, which can at times be thrilling; at others it feels that Narcifixion could just keep going on.

Driven by the compelling logic of intensifying self-obsession and self-destruction, realised with meticulously executed dance, comic self-aggrandisement and the pathos of failed connection, Narcifixion is cogent and variously funny, acerbic and affecting, but too narrow in its vision of the condition it harshly critiques. What, in the end, are we meant to feel about its narcissists? That they deserve their doom? That we’re superior to them — because Narcifixion has refused to implicate us? That we see no way out?

I appreciate having been provoked by Narcifixion, and enjoyed the opportunity to view it more closely a second time. Viewed onscreen, the production’s eerie, no-where ‘set,’ comprising only highly effective lighting (Steve Hendy) and spare costuming (Brooke-Cooper Scott), was reinforced by composer Jai Pyne’s texturally rich, dance-triggering score and its chilling silences. Anton and co-choreographer Brianna Kell danced admirably as if their narcissists’ lives depended on it, in manic survival workouts with locked-in look-at-me smiles demanding infinite reward.

—

FORM Dance Projects & Riverside Theatres, Dance Bites 2021: Narcifixion, director, choreographer, performer Anton, choreographer, performer Brianna Kell, composer Jai Pyne, lighting designer Steve Hendy, costume Brooke Cooper-Scott, livestream team Denis Beaubois, Martin Fox, Dom O’Donnell, education consultant Shane Carroll, producer Anton; Riverside Theatre, Parramatta, May 13 – 15 2021

Top image credit: Narcifixion, Anton, Brianna Kell, photo Heidrun Löhr

Rakini Devi, dancer, choreographer, performance artist and visual artist, reveals that the multitude of small paintings that fill one long wall of Sydney’s Articulate gallery for her exhibition Inhabiting Erasures: Embodying Traces of The Feminine, “are what I call ‘dancing on paper.’ They’re everything that I want to express, in actual journals, from which I have ripped these pages. If I didn’t have this journaling practice, which I worked on every single night during COVID, I don’t think I would have survived.”

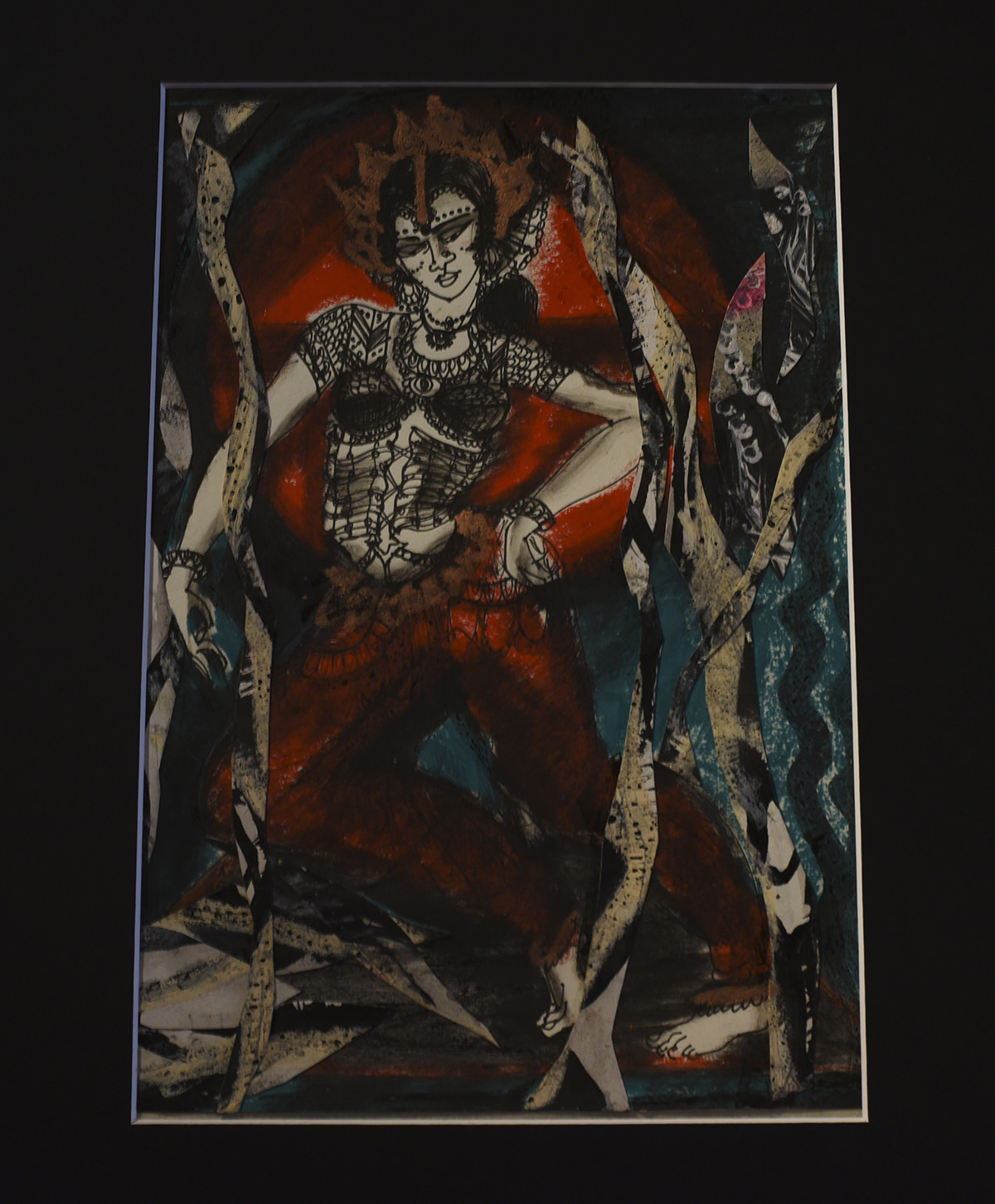

- Rakini Devi, Green Dancer, photo Rakini Devi

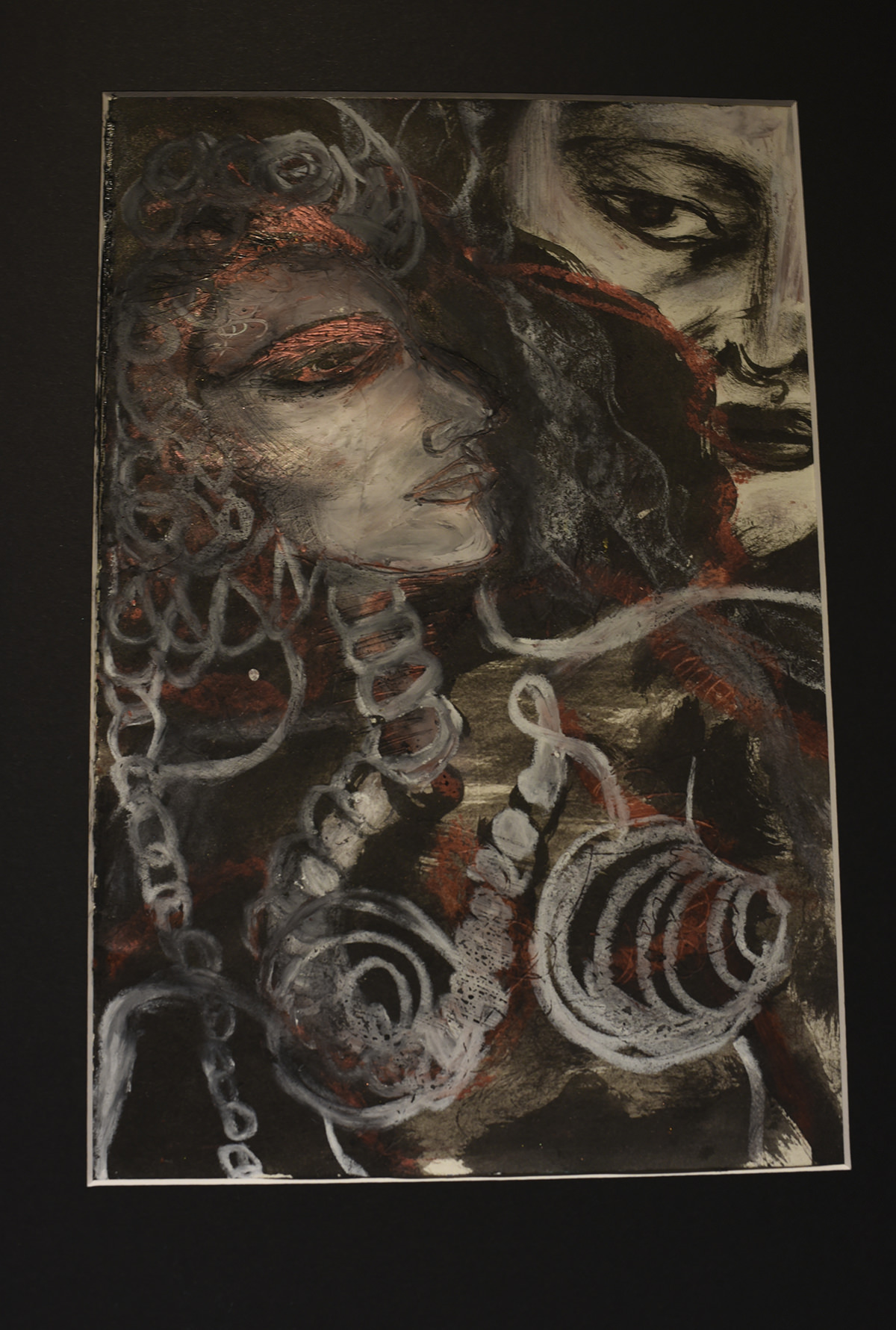

- Rakini Devi, Naga Devi (Snake Goddess), photo Heidrun Löhr

- Rakini Devi, Molten Madonna, photo Rakini Devi

- Rakini Devi, Calcutta Manga #2, photo Heidrun Löhr

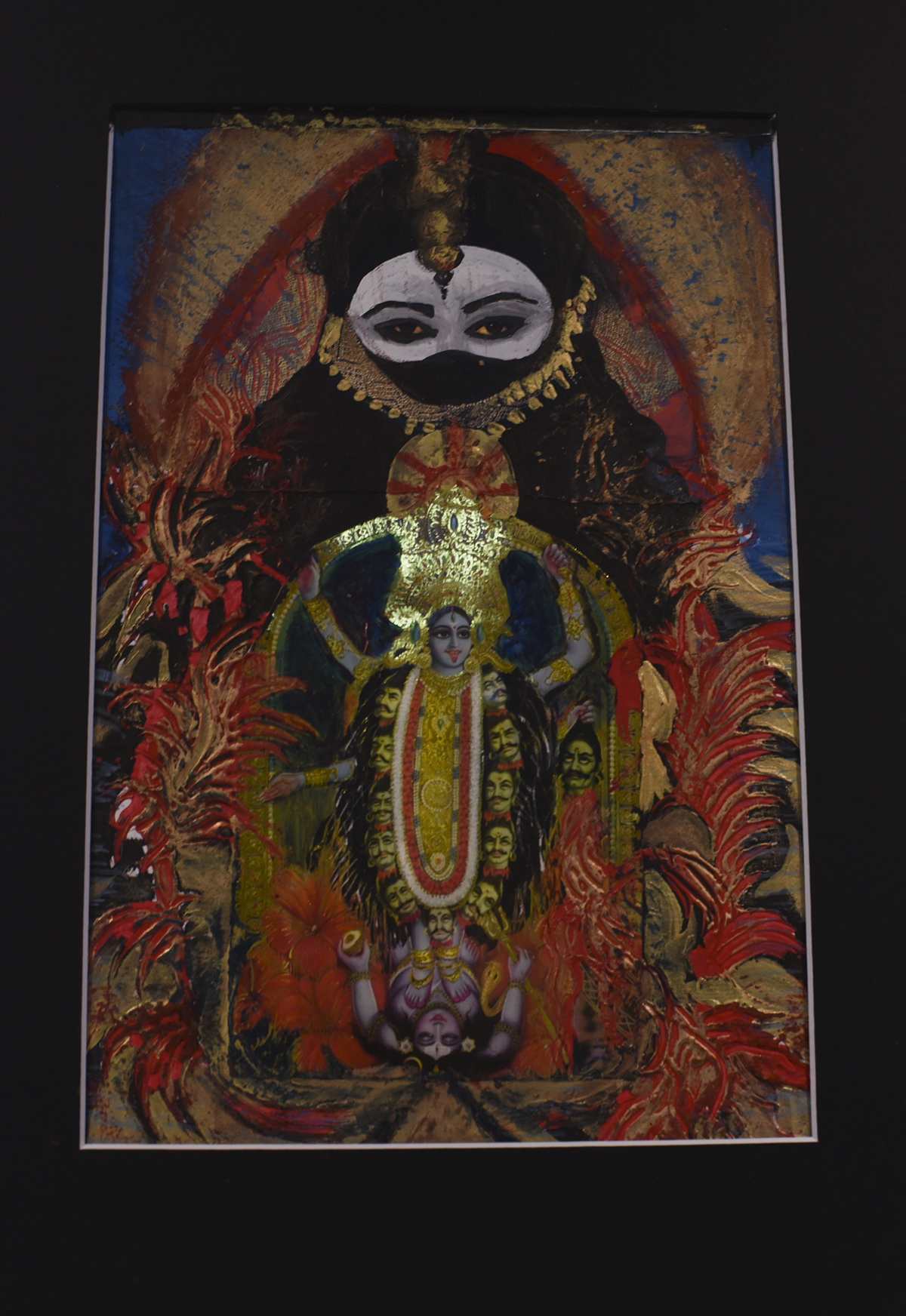

- Rakini Devi, Kali Shrine, photo Heidrun Löhr

Inhabiting Erasures hauntingly resurrects “erased” and violated women as “spectral residues” at the same time as it celebrates the artist’s 30-year career within the aura of a festival for Durga (the primary goddess of the Hindu universe), for which the long narrow ground floor gallery space on a crowded opening night evoked the ambience of a busy, narrow night-time street filled with devotional artworks.

Everything about Inhabiting Erasure evokes night labour, Freud’s dream-work, the shaping and managing of images conjured by desire, anxiety and trauma. Responding specifically to “the erasure of women through acts of misogyny and violence” in India and beyond, Devi has called up from the depths of her consciousness a phantasmagoria of fearsome goddess figures, Kali (the dark side of Durga) above all. Alongside are their cross-cultural correlatives: the Madonna and a Female Pope whom Devi has hauntingly and wittily embodied and hybridised with Kali in performance and installation. These are found in traces, including projections from performances and costumes and props on display, awaiting embodiment.

Also on the left side of the gallery is a superbly produced film with Devi manifesting as a snakily-tongued Kali. At the other end, tall hangings from a 1991 performance (“on a Ben Hur scale,” quips Devi) by her company Kalika at Perth’s PICA portray other majestic female figures. In between are two cloth canopies. Inside one is a female figure painted on the floor, Devi’s body providing the template; in the other an outline, awaiting the artist’s actual presence for opening and closing night performances.

These canopies, Devi explains, are inspired by ‘pandals,’ celebratory roadside shrines made for the annual festival in honour of Durga, Kali and all the Hindu Goddesses including the goddess of learning and knowledge Saraswati and Laxmi the goddess of wealth. Pandals range in scale from small to massive, from humble to gorgeously extravagant, sometimes produced, and copyrighted, by major artists and greeted by coursing crowds. Devi’s canopies are modest, but rich in personal, mythological and political meaning.

When I next visited Inhabiting Erasure, I had the exhibition to myself before being joined by Devi. I was immediately responsive to the artist’s “dancing on paper,” to an air of ephemerality, of figures conjured in the night, phantom presences (in Devi’s words, “traces of the (absent) female body materialising as spectral residue”), of many bodies as one, sharing the artist’s personal mark-making, classical dance poses and gestures and ritual symbols. These recur in the paintings, canopies, costumes and video, generating a connectiveness that works cumulatively to transform exhibition into installation into vibrant archive.

A long-time performer learning how to use installation, Devi asks herself, “How can I embody a space without actually being there?” Using “my own body as a template I frame myself in my own aesthetic. In all my work I imprint on my body various Sanskrit markings of sacred sounds and syllables, like the snakes that represent kundalini energy. Each symbol represents the chakras rising.”

I ask Devi, who has been drawing since childhood, what she feels each night as she paints, aside from the solace of doing it. “I paint all the things I envisage in my mind and how I feel my body moving. I have journals extending over 20 years and sometimes just by looking at a painting that I’ve done, I remember exactly what I was feeling at that time — happy, sad, tragic.” As for movement, “Well, it really does feel like my body moving; the hands and feet usually reference Indian traditional dance. It’s something I think goes back to when I was eight years old. It’s still in my body and my mind.”

We discuss pandals. Devi recalls “growing up in Kolkata and from a very young age being fascinated with the temporary shrines made every year for the goddess festivals. They are basically constructed out of cloth and bamboo. Over the years, they’ve been elevated to absolutely incredible artworks that cost thousands of rupees. Every suburb has one. As a young girl, besides being in a Catholic convent and marvelling at the icons there, I would see 20-foot idols of the goddesses Durga and Kali, as well as Ganesha. It was fascinating: the priests, the smell of incense. And then, travelling through India, I would see the tiniest little roadside shrine under a tree, a piece of cloth tied around it. I’ve always loved the idea of the canopy and decided to use it to create environments in which to frame myself. I started with the Female Pope (2010) and then in Kali Madonna (2014) in The Rocks in Sydney I constructed and inhabited a pandal-styled canopy in a shop window. Last year when I was stuck forever at home during the pandemic, I started creating all these little structures in my back patio and then in a residency at the Rex Cramphorn Studio at the University of Sydney doing chalk drawings on the floor to give them some context.”

The first canopy is draped in an attractive, embroidered pink mosquito net which, says Devi, “is of great sentimental value. It was sent to me by my aunt in Kolkata, because she knows I love mosquito nets. I love the colour. This canopy is a sort of satirical construction; it’s supposed to convey the gorgeous environment of a bride, but in fact, in India, there are dowry deaths, gender mutilation, suttee (the burning of widows) and other misogyny towards women — the stuff I’ve been researching since the early 90s. So I created this image inside. I’m actually quite attached to her. She’s not for sale.”

The figure within is white, as if naked, but not at all vulnerable. Accompanying it is “a replica sacrificial sword crafted for a 1995 show, representing Kali’s power,” and a classical hairpiece — “also worn by brides.” I also notice hair hanging eerily on the outside frame. On the floor are inscribed statistics: “2020 Australia: lockdown: domestic violence 55 deaths” and “50% of global femicides occur in Latin America.” The figure, although supine, exudes a sense of strength. Devi says, “My idea is to show that despite the misogyny and violence directed towards women, female strength is still evident. Also, I don’t want to simply house a victim. I want to really focus on and celebrate power and beauty.” The symbol at the womb-centre of the figure suggests a force field. “Exactly. You’ve got it,” Devi replies. “I don’t want to spell out everything, but people can sense it. The red sari is a typical bridal sari. Red is the colour of brides; also, for me, a representation of blood spilt. It has tragic connotations. I’m trying to show the beauty of the façade of culture that also has a darker side to it.”

We come to the second canopy which, says Devi, “is more or less a documentation of all the Female Pope performances I’ve done all over the world.” Projected images of the artist as Pope eerily grace the canopy while inside is the outline of her body: “I can embody a space without actually being there.” The Female Pope, like Kali, carries a string of decapitated heads representing the evil she has defeated. Devi explains, “I made them myself for performances I’ve done in Europe and America. I suppose it’s no coincidence that they all happen to be male, but the head, of course, mainly represents the ego; so it’s not really violence towards men, it’s actually annihilating ego.”

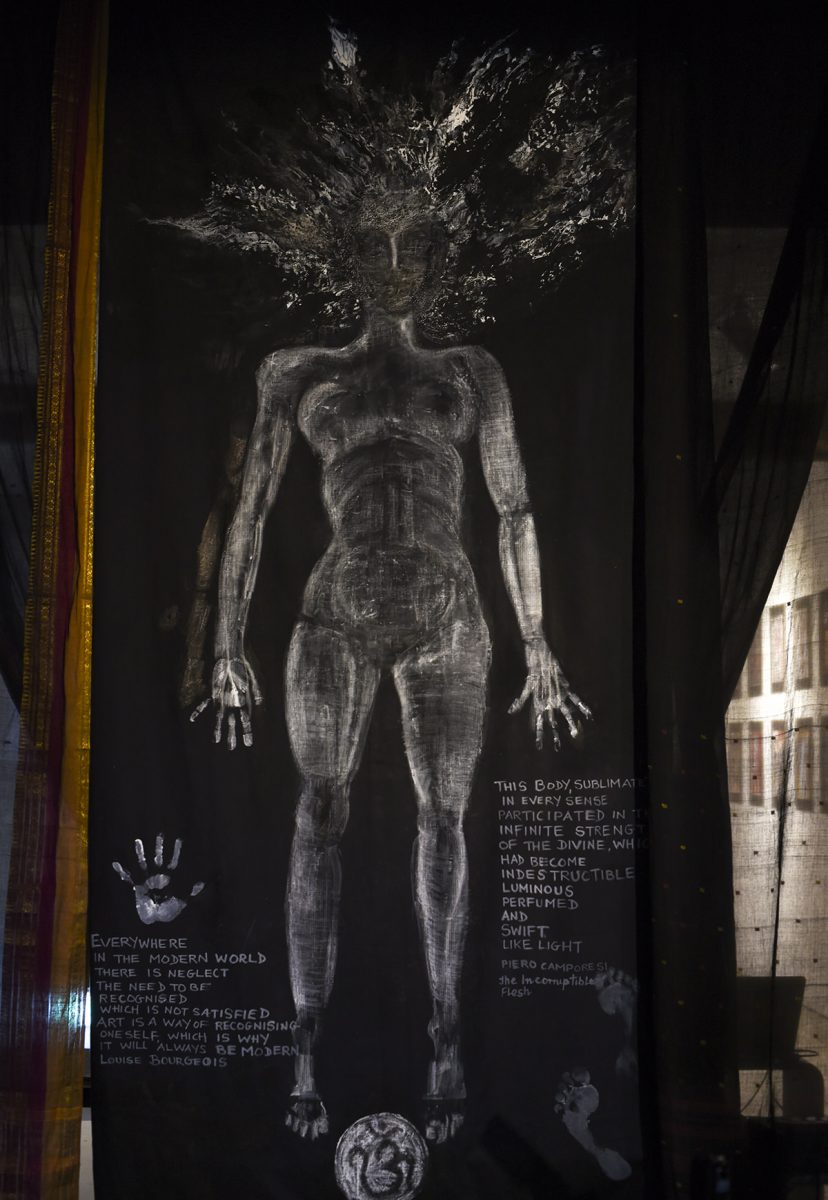

We move on to Shroud of Devi, a large, striking life-size, black and white painting of a naked woman. Lines of energy radiate from the blurred head, “like an explosion,” I say [we both laugh], “a burst of ecstasy.” Devi recalls, “I managed to dig this material out of my storeroom and it just happened to be a piece of black cloth. I imprinted by painted body onto the cloth. All the canvases are black. I love working on a black surface. It also has a negative like X-ray feel about it.”

The texts inscribed on the painting assert a self that is “indestructible, luminous, perfumed and swift like light” (Piero Camporesi, The Incorruptible Flesh, Cambridge UP,1983) and that “Art is a way of recognising oneself, which is why it will always be modern” (Louise Bourgeois, interviewed by D Kuspit, in Bourgeois, Destruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923-1997, MIT, 1998).

This hanging is a bracingly powerful work that speaks of enormous creative and psychic release. Devi muses, “It’s a very personal sort of expression. I had all this pent-up feeling, just dying to express all these things. I hadn’t worked in large scale for a very long time. I thought, why don’t I allow myself to do large scale works anymore?”

The painting includes the words “I bow to the goddess who is the soul of all yantras.” Curious about the symbols that recur in the exhibition I ask Devi to elaborate the meaning they hold for her. She explains, “The yantra is a sacred diagram just as a mantra is a sacred incantation or prayer. They are from one of my favourite books, which influences all my drawings of yantras or sacred designs. According to a lot of tantric teachers, the body is a yantra; it’s also a sacred diagram; it has sacred points. These three paintings behind you, especially the blue one; I call them ‘yantra devis’ or ‘goddesses of the yantra.’ Since the 1990s I’ve been using these symbols — the circle, the triangle, the square. I wrote at length about this in my doctorate thesis. The yantras have been an inspiration for me over the last 30 years.”

We turn to the trio of paintings. The central, intensely blue four-armed woman hovers serenely. I ask about the figure in her womb. “It’s a dancing four-armed Kali, the centre of her power. The downward triangle represents the female and the upward triangle is the male aspect/element.” She’s embodying both male and female? “Correct.” And the medium? “I always use a mixture of oils, pastels, inks and acrylics and a variety of different textures, pens, metal needles. I love layering textures.”

In the painting on the left, “A flow of red from the mouth down, represents the tongue of Kali, her energy,” says Devi. The figure’s hair too radiates with psychic energy. “It’s almost like a halo,” she adds. “There are references to the yantras and there’s my signature mark, which is the syllable or the Sanskrit letter for Kali. It’s called ‘kreem’ which is the mantra for Kali.” The symbol appears on the figure’s forehead and down the bloody flow from the mouth.

The relaxed woman in the righthand painting is endowed with an opalescent radiance, only the raised, slightly curled open right, hand perhaps evoking symbolic meaning: “This is way too pretty for my normal drawing. The face is very beautiful. I thought okay, I’ll leave her; I won’t put in any subversive elements.”

As we consider each of the journal paintings, Devi says, “Every work I’ve ever done starts off on paper, from costumes to texts, to stage setting, how the work will be framed.” Within these paintings the female body is often beautifully sinuous, sometimes a “a nude in movement…the most beautiful celebration of the feminine,” sometimes abstracted, and often referencing the poses and gestures of Bharatanatyam and Odissi classical Indian dance in which Devi trained, as in Dancer Mandala and Green Dancer. Juxtaposed with the latter is Twisted Dancer, a delightful casually contorted nude with hand and feet flexed, captured in the reverie of her movement, as if afloat. Devi is emphatic: “I’m not using actual sacred gestures. I’ve stylised them for my own art and choreography.”

I return several times to Seed Mantra, one of the rare abstract images among the journal paintings. The symbol, says Devi, “represents the chakra that is the source of my name, Rakini.” It hovers over a deeply layered and etched surface that evokes the timelessness of ancient tree rings. Devi explains the appeal of focussing on a symbol: “Distilling one’s concentration into a single letter that holds power with layers of meanings, resounding with an aura of its own, is a practice I have done repeatedly over the years, a process that gives me much satisfaction. My love of abstract painting gives me another level of concentration. While referencing and immersing myself in yantra-inspired diagrams, the process of painting them is my form of meditation. Repetitious dance moves can also produce the same sensation of escaping the earthiness and gravity of the human body, with its burdensome ego, complex desires and angst.”

This magical host of small nightworks, the fragile beauty of the pandal canopies, the towering unframed paintings and the many residues of performances past not only collectively evoke the street art celebration of Hindu Goddess culture and “the absent female body materialising as spectral residue,” of women violated and erased, but also speak to art’s ephemerality. Inhabiting Erasures is an exhibition as installation as archive: “For me,” says Devi, “it’s about leaving a legacy. I felt this was the time to address that.”

In the face of ephemerality and its erasures, it is consoling to reflect that the richness and power of Rakini Devi’s Inhabiting Erasures emanates not only from three decades of practice, but sustainingly from a several thousand-year-old cultural heritage which the artist perpetuates and idiosyncratically opens out, defying transience. Her art is born of a culture often beyond my comprehension, but that’s not say it’s beyond meaning as Devi’s imagery incorporates itself indelibly into my own night work, where art is most deeply felt. This is art that is at once modern (full of self-recognition, as Bourgeois would have it), powerfully ancient (felt like a shock of the old) and compelled by compassion that both respects and challenges tradition.

—

For more about Rakini Devi’s practice and scholarship see “The goddess & the doctorate: Rakini Devi’s Urban Kali,” RealTime, 13 Sept 2017 and a review, “Urban Kali, Face to Face with Kali,” 26 Sept 2017.

See also an interview with Rakini Devi about Inhabiting Erasure: “Real presences,” Fiona McGregor, The Saturday Paper, No. 342, March 27- April 2 2021

Rakini Devi, Inhabiting Erasures: Embodying Traces of The Feminine, technical production Richard Manner, photography Heidrun Löhr, Urban Kali video (2017) Karl Ockelford; opening night performance Rakini with Cat Hope, closing night performance Rakini with Liberty Kerr; Articulate, Sydney, 27 March-11 April

—

Top image: Rakini Devi, Canopy 1, photo Heidrun Löhr