from the simplest of interfaces: complexity

keith gallasch talks with media artist kate richards

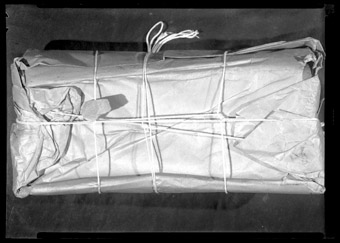

stolen TVs, from Life After Wartime

THE ROAD TO SEEING HERSELF AS A MEDIA ARTIST HAS BEEN A FASCINATING ONE FOR KATE RICHARDS WHO HAS TWO SHOWS AT SYDNEY’S PERFORMANCE SPACE IN AUGUST-SEPTEMBER. BOTH WORKS ARE TECHNOLOGICALLY SOPHISTICATED, COLLABORATIVE CREATIONS INVOLVING NOT ONLY SOFTWARE AND HARDWARE INNOVATIONS BUT ALSO ADVANCES IN DISPLAY AND PERFORMANCE METHODOLOGY. BUT IT WAS SUPER 8 THAT KICKSTARTED RICHARD’S COMMERCIAL AND ARTISTIC CAREER.

The first work, Bystander, is the latest manifestation of Life After Wartime, a suite of interactive media works created with Ross Gibson around a Sydney archive of crime scene photographs from 1945-60. This time the work will be experienced as an immersive installation after earlier incarnations as CD-ROM, gallery exhibition (which drew a huge attendance at the Justice and Police Museum, 1999-2000) and performance. Twelve visitors at a time will enter a space made up of five screens. This time, the mobility and attentiveness of the audience will prompt a computer to decide what to release of the crime scene images and narratives.

Richards’ other collaboration is Wayfarer, with Martyn Coutts, a game-based performance in which each of four audience teams investigates an unfamiliar space through images relayed by a performer whom the team direct using their voices.

the making of the artist

Sydney in the late 1970s fuelled the young Richards, just out of high school and excited by conceptualism at Sydney College of the Arts, where her sister was studying, by what people were doing at Alexander Mackie Studio, at Side Effects and the Sydney Filmmakers’ Co-op. “It was a very fruitful period. I was lucky enough to get into what later became the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) and I started working in film, which I loved, and later living in the UK I learned video through the community video sector. But I always had a hankering to do more conceptual, experimental types of work, and I didn’t feel I fitted in at UTS which was at that stage teaching a more film industry model, although a lot of good people did come out of that.”

Richards maintained her experimental film and video practice, but while teaching at the College of Fine Arts (COFA) and doing her Masters degree, “I had a concept for a work that was not linear. And, I thought, ‘How am I going to manage this?’ Bill Seaman, the American media artist, was teaching at the COFA at the time and was my supervisor and said, ‘This sounds like a CD-ROM.’ And I was away! With a solid media production background I’ve always had a horses for courses attitude—choose the media that’s going to fit the concept. What I liked about interactive multimedia was that you could bring lots of extant media to it—cinema, sound, illustration, painting and typography. And there was also a role for the audience in determining outcomes or in navigating—I liked this fourth dimension. I’ve always enjoyed working with technology so it didn’t faze me too much.”

But Richards was wary of seeing herself as an artist even though in the early 80s she’d been well known in Super 8 circles and had secured grants. “I didn’t feel that confident as a young artist. I found creativity a scary, deep thing…I’m a bit of a late bloomer.” The impulse to focus on her artistry came after eight years of teaching at COFA, as well as in the Indigenous filmmaking course at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS), Metro Screen and full time at UTS in media production.

“I was burnt out from executive producing something like 80 different projects a year and from not doing my own projects. And I’d lost the creative drive.” Richards turned to freelance work including two years as multimedia producer for the NSW Historic Houses Trust based at the Museum of Sydney. Nowadays, working on her own projects and in collaborative ventures, Richards declares, “I define myself as a media artist.” As well as the Performance Space shows, she’s exhibiting a series of photographs at the Australian Centre for Photography in October and is working on a video for next year.

Above all, Richards reveals, “It’s interactivity, as a commercial producer or as an artist, that continues to stretch me. I learn different techniques, I work with different contractors and crafts people.”

Bystander, Kate Richards, Ross Gibson

bystander

Richards describes Life After Wartime as “a suite we’ve worked on together since 1999. Ross Gibson started a couple of years earlier researching the material. We have a database of 3,000 images and about 1,500 texts from Ross as well as sounds [incuding original music by Chris Abrahams and sound design by Greg White]. We were interested in different forms of display, different forms of interactivity design, so the audience would get different affects from the same sort of material. The visual and the sound design is similar across the whole suite—it’s the interactivity design and the combinatory strategies that differ in terms of the way the audience engages.”

Explaining how this new version of Life After Wartime works, Richards says, “Bystander is based on the notion of a generative world. ‘World’ is a common notion in fairly sophisticated interactivity. You create an environment that has very simple rules and it knows what to do under particular conditions. This allows for emergent behaviour which could be defined as simple rules giving form to complex behaviours. So you try to keep the rules as simple as possible for the World. In Bystander, the world only has a few characteristics. It’s on a 45-minute cycle. Every 20 seconds it pumps out a narrative text.”

Richards emphasises that “there is no interactivity apart from where audience bodies are and how they’re moving individually and collectively.” It’s the World which is asking, “Where am I in the 45-minute time cycle? What’s that text that’s just rolled out? How is the audience behaving, how still or robust or disruptive? And then using a valency or a gravitational idea it will draw a number of images or texts to cluster around that text. It’s choosing them on the fly from the database. If the World finds itself at a certain point in the cycle and the audience behave in a certain way, it chooses a whole lot of images about Kings Cross…or a bunch of images designated as having high narrativity. The rules change over the cycle. It’s a World sending you stuff, we don’t control what comes out, just the rules.”

The five-sided space was designed by media artist Tim Gruchy who, says Richards, “with his gallery experience and knowing that most galleries don’t have the equipment we need, suggested we make Bystander portable and self-sufficient. The frame and screen have been fabricated by professional screen makers. Five computers run the work, one has the brains (the World) and the others have to prepare the images for the five projectors as well as the sound. We made the whole thing as a kit.”

Richards adds, “The beauty of this system is that we could put someone else’s database in. Part of the research imperative of the project, which was funded by an Australian Research Council grant, was how do you create an environment that enables you to put a collection in and find the patterns. And how to pace it to suit the collection.

“We made Bystander respond positively to attentiveness because the material demands it. If the 12 people visiting at a time are quiet, more content is revealed, if noisy, less.”

wayfarer

Wayfarer has been three years in development and has physical theatre performers at its centre. Richards has always been attracted to engaging with performers, working with them on film and for voiceovers: “and I’m a bit of a frustrated performer myself even though it terrifies me.”

The work was initially conceived in 2004 at Time_Place_Space [the laboratory which brought together media artists and performers over five years]: “I teamed up with Martyn Coutts and we got on like a house on fire. He’s a physical performer from Tasmania interested in technology, he’s done a few technological projects and has strong theatre production management skills. We put together a concept in about an hour from a provocation from the workshop convenors, but it’s been through various changes since.”

Richards describes Wayfarer as combining “the exploration of a strange space, live performance and interesting technologies. It’s effectively a live game. The audience groups each have a player whom they drive using voice. The conceit is that the audience is outside and the performer inside a building they don’t know. It’s timely to premiere it at CarriageWorks because a lot people don’t know the back of the building yet.”

The performers move through the building wearing small chest-mounted computers “which send streamed video to our software and audio through VOIP to the audience who communicate via microphone. The performers also have RFID readers that can read tags (which trigger films about the site), like bar codes, in the building, and also so the site knows where they are. There are key game elements—time limits, issues of agency, how much for the performers, how much for the audience. There’s a series of tasks and goals you have to achieve to finish the game and beat the clock.”

The teams will operate near each other in the massive CarriageWorks foyer, working to a large screen with their voices: “Voice is the most flexible interface you can have. Anything you say is a potential action.” As for performer interplay, “If and when the performers intersect, the software splits the screen, so that the audience see up to four points of view.”

Richards says she has been particularly influenced by the UK’s Blast Theory (see p6): “When you participate in one of their works, it alters your consciousness because they’ve got a stong social enquiry imperative, the works are well designed and not always dependent on hardware—it might be about team mentality, for example, having to ‘buddy up’ with someone for a long period. We’d like our audience to be confronted by their own behaviour, their improvising, their relationship with a performer. We want the stakes to be high, an ethical spectacle. We like spectacle, we like games but we want something gritty, to be challenged. We want moral dilemmas.”

As with Bystander, Richards says that the hardware and software can be adapted for various users, for example text-driven theatre or community projects. As for the design, she admits, “I understand it in principle but it’s hard until it’s functional.” It’s a long way away from the mechanics of Super 8, but clearly for Richards a road well worth taking.

Above all, Kate Richards is emphatic that “immersive” doesn’t mean having to push buttons, learn rules, make mechanical decisions or rely just on the intellect. “It’s in the way you move. It’s in your voice and what you say.” The game is on. Enter the ethical spectacle. Complexity.

Bystander, artists Ross Gibson, Kate Richards, visual design Aaron Seymour, interactive sound design Greg White, senior programmer & engineer Daniel Heckenberg, sound programmer Jon Drummond, installation design Tim Gruchy, Performance Space, Aug 8-Sept 9 www.lifeafterwartime.com; Wayfarer, artists Kate Richards, Martyn Coutts, software design and programing Jon Drummond, technical producer & designer Mr Snow, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sept 5-8, www.performancespace.com.au

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 4