the piano replayed & re-read

mireille juchau on gail jones’ response to campion’s film

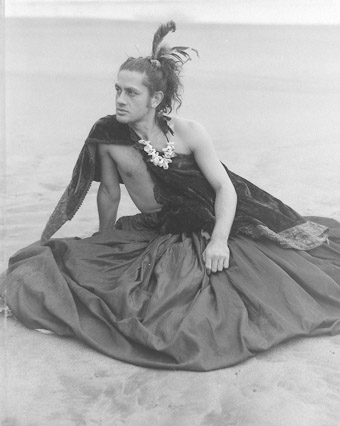

from Grant Matthews’ The Piano Series (1993)

courtesy of the artist

from Grant Matthews’ The Piano Series (1993)

“…PLAYING, NONSENSE AND STATES OF SEXUAL DESIRE ARE ALL, AT THEIR BEST, STATES OF ABSENT-MINDEDNESS, OF SELF-FORGETTING, OF ABANDON”, WRITES AUTHOR AND ANALYST ADAM PHILLIPS IN SIDE EFFECTS (HARPERCOLLINS, NEW YORK, 2006). WHEN REVISITING JANE CAMPION’S AWARD-WINNING THE PIANO, VIA GAIL JONES’ ILLUMINATING BOOK ABOUT IT, I WAS STRUCK BY HOW OFTEN THE TROPE OF PLAY OR PLAYING OCCURS IN THE FILM AS A METAPHOR FOR SELF-PRESERVATION AND ABANDONMENT.

For those who haven’t seen the 1993 film, written and directed by Campion, the plot centres on the (voluntarily) mute Ada who arrives in New Zealand with her daughter, Flora, to marry the prudish white settler, Stewart in about 1860. We sense the marriage is doomed even before Stewart trades Ada’s beloved piano to another settler, Baines, for land. But Stewart is later cuckolded when Baines makes his own trade with Ada, selling back her piano, key by key, in exchange for sexual access to her.

The Piano, Jones’ intelligent and penetrating essay—the latest of Currency Press’ Australian Screen Classics—is assembled into nine chapters examining the cultural, historical and social aspects of the story and the aesthetic techniques used to represent these (“containment and excess, the rhythmical unrolling of images…an interior turbulence, a spill into dimensions of sublimity and vastness…”). Most compelling of these is Jones’ account of the complex sexual entanglements between Ada, Stewart and Baines and the piano, “a prosthetic object…for [Ada’s] missing voice.”

Playing, in Baines’ house, involves a series of initially sexually predatory encounters, where he circles and touches Ada as she bends, absorbed, over the piano. Ada “plays in a self-enclosed, private way, closing her eyes at points of rhapsodic engagement… As she enters the music, she is self-pleasuring…” The evocations of Ada’s playing in The Piano suggest the connection between play, creativity, expression and self-abandonment. Sex, which eventually occurs between Ada and Baines, is, as Phillips writes, “what threatens play, what constantly threatens to put a stop to it…”

In having amicable relations with the local Maori people, Baines is portrayed in contrast to Ada’s husband Stewart, as “a kind of assimilated white man” amidst the colonial New Zealand setting. The Maori are often depicted as playful, “active and lively”, engaging in mimicry and humour at the expense of the subdued white settlers. In one scene they literally participate in a play, Bluebeard’s Castle, “a narrative of possessive and violent marriage” in which Bluebeard murders his wives. After Maori warriors in the audience leap up to save one wife on stage, interrupting the drama, they are given a lecture on the logic of theatre. This scene, Jones notes, has been widely critiqued as an example of native naïvéte—but she suggests we might consider the Maori’s actions as stemming from honourable aims: intervening in a scene about oppression and violence toward women. (This is a theme that recurs throughout The Piano, most brutally so when Stewart attempts to rape Ada after chopping off her finger in a jealous rage.)

But Jones also notes the occasionally insensitive depiction of the native people in The Piano. “[W]ith any historical drama’, she writes, ‘there is an ethical challenge to the filmmakers to assess the degree to which representations might perpetuate neo-colonial thinking.” While Campion cites her interest in 19th century melodrama, such as Wuthering Heights, as a strong influence on her style, rendering the Gothic aesthetically in The Piano can at times result in depictions of the New Zealand landscape and its people as overtly ‘other.’ The Piano’s cinematography features subaquatic qualities; the colours are dark and murky, it has a “sensibility of immersion.” But although this effectively suggests Ada’s interior, unconscious space, and represents New Zealand as “a perilous and drenching heterotopia, not for touristic or colonial satisfactions of the picturesque but otherworldly…that might dissolve the self into place in disturbing ways”, the use of filters, tone, light and colour also “enhances white skins to the point of luminosity and causes dark skins to be subordinated and vaguely erased”, writes Jones. Director of Photography Stuart Dryburgh says, “We tried to represent [the landscape] honestly, and let it be a dark place”; he strove to “recreate a kind of antique visual style drawing on 19th century colour still process” yet this notion of ‘dark places’ echoes many colonial and ethnological accounts of exotic ‘otherness’ and sounds like a white construct. How much does the eerie ‘darkness’ and strangeness in depictions of both Australian and New Zealand landscapes in many contemporary films uncritically reflect white concepts of inhospitable and hostile frontiers to be ‘civilised’ or tamed?

Despite this, The Piano is not simplistic in its depiction of either the white or native characters, though the latter contribute to the film’s milieu, furthering the themes through dialogue and action and are not central to the action. Stewart comes to represent everything dour, restrained and dull about the early settlers (their “Scottish rectitude”). His (and Baines’) masculinity are far from conventional, and both are undercut by Ada’s actions in several examples of sexual and gender play. (Apparently Campion always initiated a ‘dress day’ on set during which cast and crew had to frock up. The production diary notes: “The men love it. The most macho change their dresses several times a day… Jane says she feels much closer to her male crew once she’s seen them in a dress.”) Stewart seems only capable of sexual arousal in the face of Ada’s helplessness (he twice attempts to rape her and rejects her advances in disgust). And Baines eventually realises that his desire for Ada, as she attempts to earn back her piano, “exceeds the logic of trade.” When this “trading relationship is annulled by Baines”, Jones notes, there is a “crucial revaluation of value” changing the terms of the sexual engagement to one which allows “the possibility of reciprocated desire” when Ada willingly responds to Baines’ advances. This is a fresh reading of a sequence that other critics have called an “aestheticisation of rape.” What Jones so thoughtfully describes in discussing several readings and critiques of the film, is how this erotic engagement between Ada and Baines—“a sexual and trading narrative”—connects to the larger question of how “the primary sexual relationship in the film effect(s) the colonial economy.”

It is this ability to consider both the film’s shortcomings and strengths and to openly and deeply consider varying interpretations of The Piano without striving to reach a singular conclusion that makes Jones’ essay an invaluable resource. In its free-ranging and generous interpretations, in its acknowledgment of the film’s beauty and flaws, Jones’ account is also playful. While noting The Piano’s capacity “to alienate and entrance” she cites the range of critical responses—from gushing adoration to Stanley Kauffman’s dismissal of the film as an “over-wrought, hollowly symbolic glob of glutinous nonsense.” Jones’ background as an academic in cinema, literary and cultural studies and her considerable talents as a writer of four novels is evident in this rigorous, thoughtful and effortlessly composed critique.

Gail Jones, The Piano, Australian Screen Classics, Currency Press, Sydney, 2007

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 34