the incessant alert of responsibility

dion kagan talks to kirsten von bibra about helen cixous

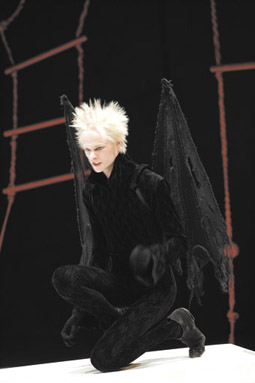

2007 VCA Graduating Company’s production, The Perjured City

photo Jeff Busby

2007 VCA Graduating Company’s production, The Perjured City

FOR KIRSTEN VON BIBRA, THE PERJURED CITY’S TWINNING OF GREEK DRAMA AND FRENCH THEATRE CONSTITUTES THE MARRIAGE OF TWO GREAT PASSIONS. AS DIRECTOR, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, DRAMATURG AND TEACHER, SHE HAS NUMEROUS CREDITS IN BOTH THESE TRADITIONS. HER OWN GRADUATING PRODUCTION IN 1983 AT THE VCA WAS A GREEK TRAGEDY. AND YET, FRESH FROM THE 2007 VCA GRADUATING COMPANY’S PRODUCTION OF HELENE CIXOUS’ EPIC, FOUR-HOUR PLAY, SHE SPEAKS OF THE EXPERIENCE IN HUSHED, REVERENT TONES THAT ONLY HINT AT THE EXTRAORDINARINESS OF THIS DIRECTING EXPERIENCE.

I always work with a lot of heart, but I think that was something very special, that play. It’s a privilege to work on material like that… It’s so vast in its intellectual breadth, in pulling together all these extraordinary stimuli of the imagination…Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, Greek mythology, and contemporary history. God, it’s such a blast!

It’s also been physically and intellectually exhausting. Von Bibra has enjoyed an 18-year role as project director with the Melbourne Theatre Company’s Education Program, was joint artistic director of Theatre of Spheres, has worked with contemporary, classical and devised theatre in the UK and throughout Europe. In Melbourne, she has directed at Playbox, La Mama, St Martins, National Theatre and others, studied psychonanalysis for four years and in 2006 was co-recipient of a creative development grant from the Full Tilt program at The Arts Centre, with performance artist Andrew Morrish. The Perjured City, she confesses, might have been the biggest challenge of her career: as well as an epic drama of tainted blood, corruption, marginalisation, vengeance and injustice, the production was a visual spectacle involving puppetry, stilt-walking and rope-climbing: “to rehearse that play in the time that we did, just about killed us.”

a theatre of elevation

So, why The Perjured City? Why a play so long and difficult? “It’s a lot to do with the passion”, von Bibra says. “[Cixous is] so motivated to talk about social issues…” The director shares Cixous’ interest in what she calls the “incessant alert of responsibility”, viewing theatre as an agent of social activation and as an act of elevation; a means of alerting people and awakening them to injustice, here the illness and deaths of some 5,000 people given HIV infected blood transfusions in France in the 1980s. So, what are the theatrical and stylistic elements that produce a theatre of elevation? How do you incite consciousness and engagement, perhaps even action?

“Choral work, where you’ve got vocal strength in a number of people speaking together, and they’re unified” is pivotal, says von Bibra. The inclusion of a chorus, a staple of Greek drama, was informed by Cixous’ study of the French Resistance fighters of World War II, but there’s so much historical slippage, or glissage, in this play, her Chorus could be eighteenth century revolutionaries, or the students of the 1960s uprisings. But the play’s most impassioned outcry against injustice is the collective voice of the Furies: “Cixous awakens the Furies after 5,000 years of sleeping. She awakens them through outrage and indignation that this horrendous crime, this blood crime, has occurred.”

unwomanly power

The Furies needed to be a potent force without sliding into burlesque. There’s a lot of humour in the way Cixous has written them; and they’re very much related to the grotesque women of Le rire de la Méduse (The Laugh of the Medusa, 1975), Cixous’s seminal essay championing the ways women might use rage, laughter and generally unruly, unwomanly behaviour as a form of agency and resistance. It’s a paradigm of femininity that is both erotic and abject. Von Bibra initially conceived the Furies as completely stylised, with slow and synchronised gestures and movement: stepping forward, rubbing their palms together, wringing the stain of blood from their hands like Lady Macbeth. But as the performance blueprint evolved, they became more naturalistic, allowing for increased freedom of movement and expressiveness. Costuming them was challenging. Aeschylus never actually described them beyond the physical repulsion and terror they evoke. “All you get is the residue from the other…Isn’t that the nature of the fear of the other? [Like] the ‘War on Terror.’ What is ‘Terror’? If you had to personify ‘Terror’, what does it look like?’ So then, how do represent the Furies, characterising what is perhaps more powerful in abstraction?”

“They were always going to be red”, the director states emphatically. “There are mythological references to them wearing black, but I really wanted them to be Passion…and the notion of blood too is important in terms of what they were avenging…There’s a femininity about them, but their dresses were distressed at the bottom and sewn in ribs with veins so they were basically a seething mass of blood.” But the emphasis had to be on language and utterance. Von Bibra’s biggest focus is on the dissolution of language, another motivation for choosing Cixous, who deliberately implants meaning into grammar, punctuation and line formation.

enunciation & pronunciation

“More than anything I felt it was about the language of the Furies, so I felt that visually I didn’t want to create a lot of pulling of focus…The work on the Furies was much more invisible than the visible…I’m very passionate about the acts of enunciation and pronunciation, [so, we] did a lot of work on the approach to utterance. For example, when the Furies say: “We disappeared for 5,000 years. No one heard us. Not even, c-c-cough”, [there’s] the repetition of ‘cough’, and the [emphasis on] how you enunciate the word ‘cough’, and the whole notion of onomatopoeia.”

Cixous uses “amphibology”—an ambiguity of language achieved through grammatical structure. The play’s title, The Perjured City is an example. Has the city been lying? Or, has the city been lied to? Amphibology also functions in the play’s constant glissage of address. There’s a deliberate ambiguity around the use of the word “vous.” Is it referencing other characters on stage or the audience? There’s a lot of breaking of the fourth wall, and the dialogue slips easily between fourth wall and direct address. Von Bibra considers this the strongest component of the play’s activist rhetoric.

the others

But it’s the theatricality of Otherness that is its most compelling aspect. In the house of Cixous, the voice of the Other—the repressed, the politically marginalised, the collective unconscious, the dead—acts as a social agent. In The Perjured City, the children who have died from HIV/AIDS as the result of a contaminated blood transfusion, return from beyond the grave, singing a call to arms. The VCA production team reincarnated them in the form of small wooden puppets. When they appeared, the children were always aspiring upwards, always climbing—a nod to the concepts of elevation and transcendence. Similarly, the red ropes surrounding the set became a sort of trapeze for the venerable souls of the Chorus, who could perch above the trials that unfolded beneath, literalising a sort of elevation.

the word

To bring this spectacle together, the players drew on the VCA’s three-tiered rehearsal model and extensive research into the play’s backgrounds. The tiers commence with “dropping in”, a process of visualising individual words and meanings and attributing personal significance to each, word by word. This is followed by an abstracting process—a physical and imaginative improvisation of the universe of the play. The actors then have a very strong kinaesthetic and muscle memory recall when they finally create the “blueprint”, the shape of each scene.

Von Bibra relates a very stirring moment from the thick of this emotionally gruelling process. About three weeks before opening night, the director, cast and crew received a message from the playwright herself: “Don’t act, live it.”

See John Bailey’s review of this production of The Perjured City, “The ghosts of bad blood”

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 42