a very strange kind of time

bryoni trezise moved by sleepers wake! wachet auf!

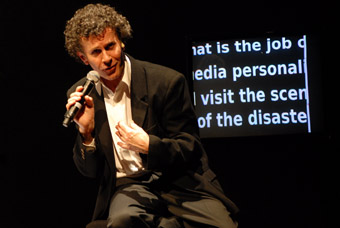

Nigel Kellaway, Sleepers Wake! Wachet Auf!

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nigel Kellaway, Sleepers Wake! Wachet Auf!

OUR NAMES ARE SPOKEN ALOUD INTO A DIMMED SPACE AS WE ENTER. THE CHARACTER ‘NIGEL’, THE VERY LAST TO ARRIVE, HOLDS OUR COLLECTIVE PRESENCE AND SUGGESTS THAT TOGETHER WE “DECIDE WHEN THIS PERFORMANCE BEGINS.” WE WAIT. FOR A TIME. OUR EYES FOLLOW HIS EYES, DIRECTED OUTWARDS. THERE IS A PIANO, CENTRE. A VIDEO MONITOR. POOLS OF LIGHT DELICATELY SPLOSHED ACROSS A DISTANT SQUARE OF TARQUETTE. A MEMORY OF AN ACTION, PERHAPS. A FLEETING GLIMPSE OF PERFORMANCE? OF MOVEMENT? A TRACE OF WHAT HAPPENED, OF WHAT WILL HAPPEN WHEN BEGINNING FINALLY BEGINS?

Nigel Kellaway’s solo performance Sleepers Wake! Wachet Auf! is concerned with memory and forgetting. The title, taken from a cantata written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1731, implies the opposite to lullaby, and yet, Sleepers Wake! mirrors Bach’s own entry into the riff of dreamscape. We exist with Nigel in a zone that slips, like sleep, between loss and longing, caress and fantasy, pain and forgetting. Our journey is heavily somnambulant. We are half-teased into waking by the trickery of words or the sensuous strain of melody. We are all made witness to a very strange kind of time.

Is Nigel in mourning? Is he traumatised? Amnesiac? He has certainly forgotten something. We watch him chase memories—remnants of narratives, half-told stories, the shadowy footsteps of a dance. These are the compelling traces that he longs to unravel, but they only ever return in the fickle shape of “bluff.” Nigel’s memories are fake, a mocking ruse. He merely “appears to have a past.” Instead, his reminiscence is the junky bric-a-brac of other people’s stories: dim and fading musical motifs, punchlines and ‘wound culture’ television grabs, repeatedly leading both us and Nigel to the wrong scene at the centre of the wrong crime

French novelist Marcel Proust was enamoured of memory and its tendencies for loss and longing. Sleepers Wake! was conceived as a collaboration between four distinguished performance writers. Amanda Stewart, Josephine Wilson, Virginia Baxter and Jai McHenry were each invited to respond to Kellaway’s identity as performer through notions of memory. The collaborative writing effort creates a sense of a man who stands amidst broken narrative—a postmodern Proust gone awry. And yet, these narrative breakages speak less of collaboration and more of a certain kind of experience. Their fractures paint Nigel as a man who is balancing tenuously on the cusp of himself.

At the centre of the space are three musicians (Michael Bell, Margaret Howard and Catherine Tabrett) who sensitively sustain Nigel’s melancholia in compositions that Kellaway has adapted from Bach’s original Goldberg Variations. What we hear are “variations upon variations”—music that is ‘quoted’, recollected, eclectic. It lullabies on recurring motifs that return, each time with a slightly different twist, engineered to sink us into the sense that we are looking at the same problem from perhaps a different angle. Kellaway’s reference to Roy Orbison and eighteenth century music boxes sounds out a tinny, kitsch nostalgia above the depth of Bach. Another version using Kurt Weill has dramatic spunk in its pace.

These incongruous musical themes elide dream with recollection. They make Nigel dance before us, stand before us and, interestingly, resist the memory of Kellaway’s own musical skill. Kellaway, the performer, does not play (until the very end), although we get the sense that Nigel, the character, has a lurching itch to do so. The different textual variations cleverly merge to produce writing that is in different degrees elegant, potent, smug, syncopated and raw. In one narrative, Nigel confesses to a psychiatrist, only to end with a gag and the punctuating resonance of canned laughter. In another, he has received a letter from a lover who has apparently left him, but has got all the facts wrong. For a start, Nigel never had a pet rabbit, nor did the lovers own a holiday house.

This delicate stepping between worlds both in space, music and text makes Sleepers Wake! a complex take on the oftentimes symbiotic relationships between memory, performance and self. In this rendition, a postmodern Proust gives way to a cynically philosophical Hamlet. “To B or not to B?”, Nigel coyly asks when tinkering at the keyboard. And yet this reference to bigger questions is not to be taken lightly. I was moved by Sleepers Wake!. There was a sense of inevitability about it all, the pathos in Nigel’s not knowing but continued attempts at being. The writers cleverly use memory to ask bigger questions around what all of this “presence”—this “Nigel Kellaway Hour”—is really about.

The skill in Kellaway’s performance is in his exquisite command not only of text, timing and audience, but in his obvious joy in knowing exactly what we do not. Kellaway understands the fickle nature of memory, which is why he disappears before our eyes a little too quickly. We are left with a trace of a gesture, the afterglow of human sentiment, an energy that lingers alongside what has already become just a distant memory of music. There’s the rub.

Sleepers Wake! Wachet Auf! composer, director, performer Nigel Kellaway, writers Amanda Stewart, Virginia Baxter, Jai McHenry, Josephine Wilson, musicians Michael Bell, Margaret Howard, Catherine Tabrett, lighting designer Simon Wise, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, June 7-16

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 43