palace grand: theatre of the self

andrew templeton

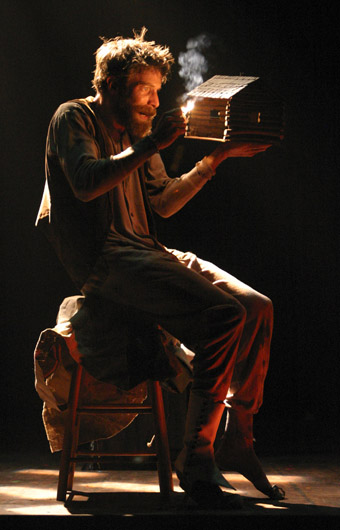

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand

photo Tim Matheson

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand

Palace Grand ends with an image that would make an effective gallery installation. We look into the interior of a wood cabin where a man, wrapped tightly in a sleeping bag, lies stretched out on the floor like a corpse. Through a window above the body, we sense the desolate, killing beauty of the North. This wooden cabin is the Palace Grand—or, more correctly—the Palace Grand exists inside the man, the central character of this piece.

I don’t think Jonathan Young, the creator of the work and its sole performer, or his colleagues at Electric Company would mind too much that I gave away the ending. If Palace Grand were a murder mystery—a genre it evokes—it would fall into the how-he-done-it rather than who-done-it category. It is clear early on that the two central characters, Walker and Tracker, are really one and the same person and that the driving force of the piece is seeing how the two halves will come together, what will happen when they finally meet at the Palace Grand.

Of course they never formally meet but are brought together for that final, haunting image. The majority of the production details the individual but inter-connected journeys of the two. First is Walker who in the late 19th century travels to the far north of Canada, to Lousetown with intentions of taking over an abandoned mining claim. I think this is the back-story although the fractured manner of the storytelling means that it is sometimes difficult to follow. The key thing to know about Walker is that he’s trapped in a cabin in winter and seeking solace in writing, the only way left for him to impose order on the world while suffering the worst case of cabin fever—ever. The second narrative strand follows Tracker, who has taken on a commission from an anonymous source to hunt down Walker. Tracker carries with him an old fashioned recording device and also relays his findings to a third character, an operator at a remote exchange who forms a sort of analogue to audience.

Associations to do with writing and transmission are central to Palace Grand. Walker never speaks; instead we see his writing projected across a black scrim that frames the playing spaces. This writing is accompanied by the sound of a scratching pen. Except for one pivotal sequence when he arrives at the Palace Grand, Tracker also never speaks; instead Young mimes to a pre-recorded voiceover. Young is a tremendous physical performer and realises the full comic potential of this conceit while—on the other side of the narrative coin—wordlessly evoking the madness and loneliness that grips Walker. My sense is that neither Walker or Tracker—nor the operator for that matter—are ‘real’ but instead are creations of the body we see at the end of the work. In this way, Palace Grand is about the unreliable narrator. Is the body at the end meant to be Walker or is it a third (really a fourth) character? Is this ‘narrator’ from the 19th century or is the whole set up merely a fabrication—a 21st century imagining of a 19th century story? As Walker’s words keep reminding us, don’t trust what you read.

Who, then, is the ‘story’ about? I suspect it is about Young himself. Palace Grand seems a meditation on the dual and inter-related processes of creation (Walker) and performance (Tracker) that go into producing theatre. In a very postmodern conceit, the work is really about the work itself. In previous productions, Brilliant and Studies in Motion, the Electric Company explored the relationship between eccentric geniuses and technology, Nikola Tesla and Eadweard Muybridge respectively. In its own way, Palace Grand is a companion piece to those works. Instead of electricity or photography, it is about Young’s relationship to the creation and use of the machinery and artifice of theatre. This sense of theatrical artifice informs the production in the rigorous and beautiful manner that we have come to expect from the Electric Company.

The playing space is divided into a series of cramped boxes that look as if they’ve been carved out of the darkness. The square playing spaces echo not only the stage of theatre but also the cabin window we see at the end. The boxes are connected by a rabbit warren of tunnels that Young moves through deftly. There are also wonderfully inventive moments, including a rocking chair that turns into a sled pulled by a stuffed dog and a small steamer ship with a puff of cotton wool coming out of the smoke-stack. As in all Electric Company productions, this low tech stage-magic is offset by high-tech projections.

When Tracker finally arrives at the cabin in Lousetown, he doesn’t discover Walker but instead finds himself—or is it Young—on the stage of the Palace Grand, a vaudeville theatre, the kind you might find in a Gold Rush town. For the first time, the performer speaks instead of miming to his own voice and there is a moment of vulnerable confusion as Tracker tries to understand what is happening to him. As the curtain behind him draws back he finds not the expected audience but a pair of mechanical hands clapping eerily. His hunt for Walker is not over. He descends into another box, below the main playing space. This is perhaps the abandoned mine shaft that exists below the cabin itself. We are then treated to a series of images of struggle, the most effective being Walker/Tracker/Young climbing up a ladder towards the audience as if emerging from a mine-shaft. I wish the production had ended with this image. It had a powerful sense of a real person emerging from darkness—from the depths of insanity. However, like a Hollywood movie there are a couple of false endings, including finding the pages of Walker’s manuscript stuffed in a sleeping bag, before we get to the final image of the body lying on the cabin floor.

Electric Company, Palace Grand, writer, performer, set designer Jonathan Young, director Kevin Kerr, lighting and set designer John Webber, video designer David Hudgins, additional video Jamie Nesbitt, properties design Rick Holloway, additional properties Stephan Bircher, sound design Kevin Kerr, Meg Roe, Allessandro Juliani, movement Serge Bennathan, costume design Kirsten McGhie, scenic painter Marianne Otterstom, technical director Harry Vanderschee; Waterfront Theatre, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 11