playing the moon

christy dena on the fate of new media art

Shiralee Saul, What Happened to New Media Art?

photo Rebecca Wong

Shiralee Saul, What Happened to New Media Art?

ON THE LAST DAY OF THE FOURTH AUSTRALASIAN CONFERENCE ON INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT AT RMIT IN MELBOURNE DARREN TOFTS CHAIRED A PANEL DISCUSSION THAT BROUGHT TOGETHER A SMALL GROUP OF PRACTITIONERS, CURATORS, EDUCATORS, ACADEMICS AND CRITICS—SHIRALEE SAUL, PHILIP BROPHY, MARCIA JANE AND MYSELF—TO DISCUSS “WHAT HAPPENED TO NEW MEDIA ART?”

Conference participants who for the last few days had debated artificial intelligence approaches to storytelling, architecture in online virtual worlds, playing in streets and with mobiles, design, philosophical and methodological issues to do with gaming of all stripes, trudged into the morning session expecting to be snapped out of their conference dinner hangovers with a feisty debate. Alas, they witnessed no blood splatter. Instead, what occurred was more a meditation on “playing the moon.”

In 1937 Chinese writer Lin Yutang wrote “The method of ‘playing’ the moon is to look up at it from a low place when it is clear and bright, and to look down at it from a height when it is hazy and unclear” (Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, Oxford University Press, Melbourne). One could say then that Tofts framed the discussion with the provocation that the moon (new media arts) is in its hazy and unclear phase:

So was it the mobile phone or changes at the Australia Council? Why has new media art apparently disappeared from the cultural landscape? Key cultural institutions such as ACMI have made the transition from pixels to Pixar. Games criticism is thriving at a time when discussions of media art histories recede into the background. Or do we need to revise our definitions of new media art? Does anyone really care about interactivity any more? In the age of machinima and Second Life, is there still a place for ‘new’ media art?

Tofts began the session with a revived call (after acknowledging the fine activities of Experimenta, ANAT, RealTime, Scan Journal) for “advocates [of experimental art] to keep it visible, to remind us that things are still cooking in the interactive dream kitchens of the human computer interface.” Offering alternative techniques to raise awareness and facilitate critical discussion of ignored or unseen arts practices, I spoke about a program that I developed with dLux Media Arts: an art tour experienced at home, with people all over the globe, inside the online virtual world via avatar representations that share the same pixel substance as the art. I also voiced concern at the exclusion of independent new media arts practices from industry, education, policy and funding decisions. For me, the issue is that these decisions are based on a false assumption about how cultural industries are fostered. Commercial viability is often held up as a measure of success, and that success is usually equated to the technology employed. Rather than understanding the core insights and principles behind a project, many merely copy the outcomes. They clone the crust, not the kernel. This emphasis on false signs of success is one of the reasons why the insights of independent media art and artists are not being recognised or supported, and ironically results in a non-commercially viable, banal echo across the creative spheres.

The panelist who was perhaps expected to be the session gladiator was uncharacteristically mellow on the day. Philip Brophy who, as Tofts noted, was teaching media arts before such terms existed, did make a few acidic and lucid observations as to how practitioners and organisations could better address issues. That is, how the hazy moon can become clear. The panelist who didn’t see the moon as being clear or hazy, but just a moon, was Melbourne-based self-described “video artist” and educator Marcia Jane who described two of her works Ribbons (2007) and Intercept (2007).

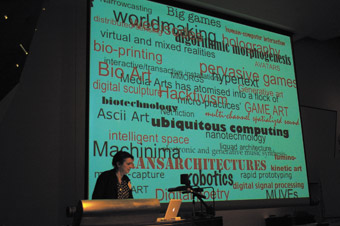

It was Shiralee Saul who listed reasons why many perceive the moon as being hazy and therefore look down on it when in fact it is clear and bright. Saul argued media arts practices exist and are flourishing but are unrecognised due to semantic haziness. With a slide projection revealing and juxtaposing term after defining term, she made the point that “media arts has atomised into a flock of micro-practices.” Robot art, generative music and Ascii art sit shoulder to shoulder with pervasive gaming, machinima and mixed realities. Indeed, “media arts has been so successful that it no longer needs or even references the art world institutions.” The problem is that some people are still “tacitly” applying old definitions of media arts (such as “film” or “video”) even though they have been “superseded.” The only people, Saul contends, who make art are “traditional artists who see an opportunity to cash in within the art world’s opportunities.” For her, media arts are no longer only in galleries; they no longer necessarily need galleries.

Many on the day felt freed by Saul’s observation: not just because it acknowledges the undeniable diversity and flourishing presence of that which was formerly known as new media arts; but also because it removed reliance on the role of traditional educational, funding, critical and curatorial structures. Indeed, Tofts noted in an email post-panel that “we are no longer dependent upon the usual curatorial and exhibition demands/protocols of the gallery/funding/advocacy system that fostered and engendered the initial phase of media arts in the late 1980s/90s.”

One of the consequences, however, of this dislocation or divergence is that ancestry is forgotten or never known. As Tofts explained post-panel: “we should also not forget [media art] history, the contexts that have developed and morphed into the culture of Web 2.0.” There is an “absence of historical knowledge that […] young artists and graduates etc should be mindful of.” This is not, Tofts continues, a generational whine, but “a fundamental issue of knowledge and of being-in-the-world’.” Indeed, the expansion of the synchronic scope Shiralee Saul offered would benefit from a complementary diachronic one. Only then will we remember we’ve had this discussion before, and understand why we’ll be having it again.

What Happened to New Media Art? chair Darren Tofts, Dec 3, part of The Fourth Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment, Storey Hall, RMIT University, Melbourne, Dec 3-5, 2007

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 27