nightshift: dangerous work

tony reck talks with the nighshift crew

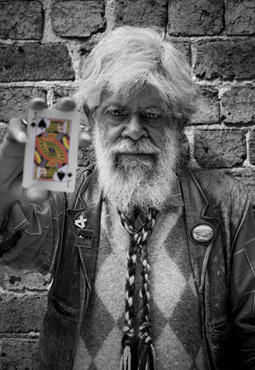

Jack Charles

photo Kerry Pryor

Jack Charles

WHEN THE AUSTRALIAN PERFORMING GROUP WAS SEARCHING FOR AN AUTHENTIC AUSTRALIAN VOICE, NIGHTSHIFT PRESUMED THAT VOICE HAD ALREADY BEEN FOUND AND, INSTEAD, WENT IN SEARCH OF ‘AUTHENTICITY’ ITSELF. THIRTY-FIVE YEARS LATER AND SITTING IN LA MAMA, THE SAME THEATRE WITHIN WHICH THAT SEARCH FOR AUTHENTICITY BEGAN, PHIL MOTHERWELL, SHIRALEE HOOD AND JACK CHARLES ARE STILL CHASING THE TRUTH. ON THE EVE OF THEIR TRIBUTE SHOW [P37] TO DIRECTOR LINDZEE SMITH WHO DIED LAST YEAR [RT78, P35], NIGHTSHIFT WOULDN’T HAVE IT ANY OTHER WAY.

You cannot prophesy the future without reflecting on the achievements of the past. The two are interchangeable, as are life and art. So when I put it to the group that a prominent Melbourne director explained his experience with Nightshift in the late 70s as: “The moral thrill of theatre, akin to electrocution”, Hood draws a sharp breath, but it is Motherwell who is vaulted upright. “We wanted to create a theatre that had the immediacy of a rock concert. Lindzee was right into Brecht: direct statements close to the bone, and pretense was an ugly word. It was a theatre of ideas, but it was visceral.”

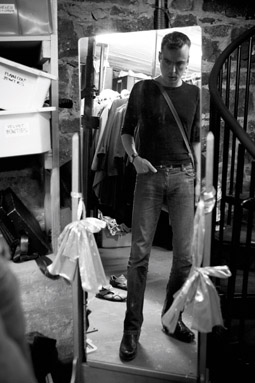

Gary Carter & Phil Motherwell

photos Kerry Pryor

Gary Carter & Phil Motherwell

As a theatre practice concerned with authentic expressions of the immediate, it makes sense that Nightshift’s current production grapples with post-apology Australia and the Stolen Generations. Hood and Charles are Indigenous Australians, and Motherwell’s play Steal Away Home is explicitly based on Charles’ life. And even though there is some ambivalence as to whether this current production is a continuum of the Nightshift oeuvre or a new theatrical collaboration, Hood, who first worked with Lindzee Smith in Perth during the 90s, takes up the charge. “Rudd’s apology is an opportunity for white Australia to have a go at understanding our story…All of the time my mother spent searching for her family she could have been consolidating her economic base. This was time wasted, and there has to be compensation…” Nightshift’s personnel may have changed since the late 60s, but its tradition of resistance continues in the form of direct political action.

Garry Carter

photo Kerry Pryor

Garry Carter

Resistance always involves an element of danger, and tying ribbons around tree trunks was never part of Nightshift’s modus operandi. Motherwell embraces Jack Charles, describing him as a “Living legend…The Ben Hall of Australian theatre”. The outlaw metaphor is apt, as Charles’ polite manner belies a charm that is as disconcerting as it is seductive. “They only ever got me when they wanted a blackfella”, he says, referring to the colour-blind casting that continues in Australia to this day. And opportunities for Charles were further limited due to an extended holiday at Her Majesty’s Pleasure, but he was not alone in prison. Motherwell’s addiction to heroin was once also out of control. In desperation, he robbed three banks with a hand concealed in his pocket, received five years jail with a three year minimum term, but was out in 16 months. He recalls Lindzee Smith visiting him in that “Disneyland of despair” just prior to the publication of Motherwell’s little known classic, Dreamers of the Absolute [a play based on the transcript of the trial of anarchists in pre-revolutionary Russia; it was performed by Nightshift in Melbourne in 1978 , Troupe in Adelaide in 1979, and Smith directed it for the Adelaide School of TAFE in 2002. Ed]. “Lindzee waltzed into the Governor’s office with a secretary on his arm and declared: ‘I’ve got some business to discuss with Mr. Motherwell.’” After Smith’s visit to Pentridge, A Division would never be the same again.

Shiralee Hood

photo Kerry Pryor

Shiralee Hood

In discussion with the Nightshift ensemble, the talk always oscillates between the stage, the page and that book of life that is a memoir of the street, be it inner suburban Melbourne or the grimy avenues of New York. So I put it to Motherwell that Dreamers of the Absolute is not just a study of the revolutionary impulse but also a manifesto for the theatre terrorist. “Dreamers” he says, “grew out of the anti-war movement. It wasn’t about a metaphorical terrorism, more a terrorism by the State; an established order that had to be undermined…I mean, we’ve only got the Pentagon’s word on terrorism, and we’ve learnt not to trust that, haven’t we?” So true, but why in Lindzee Smith’s written introduction to the play did he quote and thereby personalise the line, “The terror’s a cross it’s so hard to bear”? And why did Motherwell cast himself in the role of the revolutionary, Alexis? A wry smile appears in one corner of Motherwell’s mouth. We both know the answer to that question, but we’re not about to hear it today. Instead, still searching for an authentic expression of the immediate, Motherwell cracks us all up. “I used to write stuff just to give myself a part…Don’t laugh, it’s true.”

Nightshift reading

For a brief documentary account of Nightshift and its place in the functioning and the politics of the APG, if not for an evocation of the group’s powerful works, see Gabrielle Wolf, The Australian Performing Group, the Pram Factory and New Wave Theatre, Currency Press, Sydney, 2008. For vivid personal accounts of the Nightshift experience from Richard Murphet and Lindzee Smith (in an interview with Sue Ingleton), see the memoirs section of www.pramfactory.com. See also the Smith obituaries from James Shuv’us and Jai McHenry Derra at http://lindzeesmith.blogspot.com and Richard Murphet [RT 78, p35]. Phil Motherwell’s Dreamers of the Absolute was published by Yackandandah Playscripts in 1985. Eds.

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 36