returning the audience’s gaze

carl nilsson-polias: performance in the melbourne festival

PREMIERING AS PART OF THE MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL, JENNY KEMP’S LATEST WORK, KITTEN, DRAWS INSPIRATION FROM THE STORY OF ICARUS. THE WAX AND FEATHERS ARE GONE, REPLACED BY NEOPRENE AND MICROPHONES, AND KEMP’S FASCINATION LIES NOT WITH THE YOUTHFUL CURIOSITY OF ICARUS NOR WITH THE NATTY CRAFTSMANSHIP OF DAEDALUS, BUT WITH THE NARRATIVE DYNAMIC OF THE MYTH, ITS FREEFALLING VERTICALITY.

However, Kemp inverts the arc of Icarus and begins underwater. A woman, Kitten, realises her husband, Jonah, has somehow descended from the cliff outside their house and disappeared into the waters below. Her husband’s friend, Manfred, continues the archetypal nomenclature and acts as a well-worn third wheel. The ensuing action, narratively speaking, follows Kitten as she and the watchful Manfred search for Jonah but find each other—a romantic structure as old as L’Avventura. Like Antonioni, Kemp is not interested in the narrative suspense of the search, but on the other hand, neither is she interested in the relationships. The only driving force behind Kitten is the internal life of the eponymous character.

This life is refracted through the prism of Kitten’s triple casting. Margaret Mills and Natasha Herbert, regular collaborators with Kemp, as well as Kate Kendall, don’t play vastly different versions of the role, but their combined energies suggest the fracturing of Kitten’s mind. Beset by the trauma of Jonah’s disappearance, Kitten is plunging through her grief without rational anchor points—Manfred is a characterless vacuum, only capable of bankrolling Kitten’s increasingly tangential searching.

In the end, Kitten’s freefall takes her, and the audience, from the thick, submerged world of the first act, through the temperate naturalism of the second act into the stark, clinical clarity of a psychiatric ward. At this point, jumping into a liminal space of polar bears and inflated tuna, Kitten performs a concert. Kemp stays true to her inversion of the Icarian arc and finishes with this theatrical parachute, a floating denouement, where the audience leaves the theatre to find themselves in Crete.

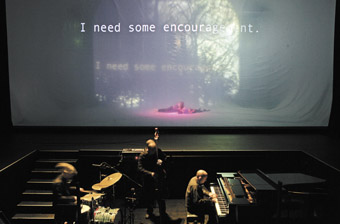

Back to Back with The Necks, Food Court

photo Jeff Busby

Back to Back with The Necks, Food Court

There are no parachutes in Back to Back’s Food Court. Bruce Gladwin and his team of co-creators have produced a formidably terrorising piece of theatre that also achieves astonishing beauty.

Back to Back is a remarkable company in itself, not least because it maintains a steady ensemble of actors. Throughout the company’s 21-year history, these actors, all with disabilities, have aimed at challenging audiences to reconsider their “unspoken imaginings.” Within this paradigm, the pieces that are created also serve to challenge and re-energise the performers—the ensemble’s welfare being integral. However, to regard the company’s work as primarily therapeutic denies the danger of the theatre that is produced and merely serves to reaffirm the binary of abled/disabled that is being deconstructed.

Food Court begins and ends with music. Led to the orchestra pit by torchlight, the inimitable trio of The Necks begin by building a slow trickle of sound in the dark—a cymbal scratch here, a solitary chord there. Their music has always created a sense of inevitability. Its driving pulse and dynamic is constantly building towards a climax that never quite arrives and a resolution that leaves no conclusions, simply space for silence.

In Food Court, The Necks meet their theatrical parallel. The action onstage opens in front of a curtain with a lone man placing a chair in the darkness. He then walks downstage, removes a white marker from the floor, and places it at the foot of the chair. A brilliant conceit—is the mark wrong, or is he? And in that question, in that moment, we are faced with our own judgment and perhaps taken aback by his confidence, his precision and his comedic sensibility. It is the first delicate, perfectly-pitched note.

Then, like figures from a Diane Arbus monograph, two women, clad in lurid gold leotards, take to the stage and begin an innocuous conversation. “Have you ever eaten a hamburger?” But with the arrival of a third woman at the other side of the stage, their attention and manner shift markedly. They begin to tease her about her intellect, her personal hygiene and her weight.

The barrage of abuse continues and becomes both abstracted and reified behind what appears to be a plastic scrim. In fact, it’s an inflatable cube of plastic that diffuses the shapes inside it while providing front and rear screens on which to project images and text. Beyond its practical attributes, the bubble acts like a Jungian ewer of the objective psyche—displaying a dreamlike state of archetypes engaged in sadism, torment, desire and struggle. Throughout this, The Necks drive on, carrying us through a forest of our own shadows.

Finally, our voiceless victim finds herself alone. It has taken 50 minutes for her to speak and, when she does, her voice cracks the air with a rush of forthrightness tinged with venom. She speaks the words of Shakespeare’s Caliban (“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises…”) and, in so doing, throws off and embraces the weight and complexity of theatrical representation and history, leaving us both punctured and inspired.

Shakespeare is given another rather different outing in OKT/Vilnius City Theatre’s accomplished production of Romeo and Juliet. The Lithuanian company is headed by the wry, floppy-haired Oskaras Korsunovas, who treats the text with élan—setting the action in rival bakeries and giving the story both the seriousness of social drama and the pep of bawdiness.

Korsunovas’ first gambit is a textless overture of competition, envy, sex and curiosity. The large cast immediately display their physical agility and alacrity, zipping from vignette to vignette across the steel bench tops. The set has both the whimsy and the darkly fantastical detailing of a Jeunet and Caro film and the posturing of the Montagues and Capulets is cleverly undermined by the mirror-image sameness of their respective kitchens. Korsunovas reveals that, for all their fear and loathing, their differences are merely imagined, yet this, in turn, renders them all the more tragic.

From this departure point, Romeo and Juliet steadily develops and expands. It captures the expressive youthfulness of its romance and matches it to the deep ferocity of its older generations. It also builds up a bank of imagery based on the vocabulary of the kitchen—ladles become weapons of masculine scorn, flour gives both life and death—that pulls the play back into the concrete world of social drama without in any way diminishing it. As it began, the production concludes wordlessly, but now, rather than hubristic poses, the tragedy is rendered by a silently aching collapse.

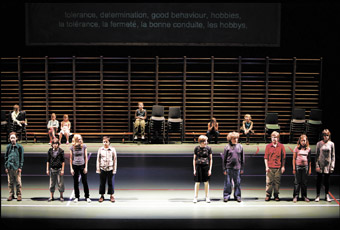

Victoria, That Night Follows Day

photo Phile Deprez

Victoria, That Night Follows Day

In Tim Etchells’ That Night Follows Day, there is no such poetic physical imagery. That is not to say that there is no poetry—the wonder of this production is in its essentialism. Working with the Belgian company Victoria, Etchells has crafted a brilliant provocation in a deceptively naïve guise.

The cast of sixteen children are a chorus of voices listing with mantric clarity the ways in which adults construct the cosmos around them—“You feed us. You dress us…You tell us to be quiet…You act surprised.” The children stand across a stage decked out in the features of a multi-purpose school hall. It is a beguiling and carefully created simulacrum—the chairs are the right size, the playground antics seem genuine, the screen for surtitles even has the powdery finish of a chalkboard, surely the clothes worn by the children are their own. Of course, the clothes are not their own, they are costumes, and the playground scene is choreographed, after all, this is theatre, this is artifice. But Etchells also knows that his audience of adults look to children not for artifice but for authenticity, for that elusive prelapsarian truth.In this respect, That Night Follows Day is as much a show about theatre as it is about the adult-child connection. Like Food Court, it engages the audience with an artifice that subtly subverts the traditional discursive structures of spectatorship—not by literally stamping on theatrical convention but by metaphorically returning the audience’s gaze. As a result, both pieces provoke questions, not answers and shift our perspectives rather than merely pleasing them.

Melbourne International Arts Festival: Malthouse, Kitten, writer, director Jenny Kemp, performers Chris Connelly, Natasha Herbert, Kate Kendall, Margaret Mills, designer Anna Tregloan, composer, sound designer Darrin Verhagen, lighting Niklas Pajanti, choreographer Helen Herbertson, Malthouse, Oct 8-25; Back to Back Theatre, Food Court, director, designer, devisor Bruce Gladwin, performer-devisors Mark Deans, Rita Halabarec, Nicki Holland, Sarah Mainwaring, Simon Laherty, Scott Price, Sonia Teuben, Brian Tilley, music The Necks, set design & construction Mark Cuthbertson, lighting design, technical direction Andrew Livingston, bluebottle, animated design Rhian Hinkley, sound design Hugh Covill, costumes Shio Otani, Malthouse, Merlyn Theatre, Oct 9-12; OKT/Vilnius City Theatre, Romeo and Juliet, writer William Shakespeare, director Oskaras Koršunovas, set design Jurate Paulekaite, Arts Centre, Playhouse, Oct 22-25; Tim Etchells and Victoria, That Night Follows Day, concept, text, direction Tim Etchells, design Richard Lowdon, lighting Nigel Edwards; Malthouse, Merlyn Theatre, Oct 22-25

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 3