ecstasy & other states

keith gallasch: sydney performance

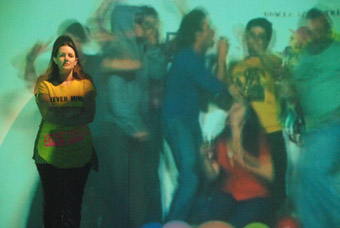

Melita Jurisic as Cassandra, The Women of Troy

photo Tracey Schramm

Melita Jurisic as Cassandra, The Women of Troy

OUR WRITERS IN MADRID, MELBOURNE, BRUSSELS, AND TOKYO IN THIS EDITION OF REALTIME REPORT BEING AWESTRUCK BY WORKS OF ART. AS JOHN BAILEY AND JACQUELINE MILLNER WRITE, THAT STATE OF BEING HAS NOT BEEN FASHIONABLE: IN ARTISTIC PRACTICE DISTANCING REMAINS DOMINANT, AN INHERITANCE OF MODERNISM, “A MOVEMENT…OFTEN CHARACTERISED IN TERMS OF THE TERROR OF THE SUBLIME”.

In this article I look at my experience of the Barrie Kosky-Tom Wright adaptation of Euripides’ The Trojan Women. I also share reflections on Complicite’s A Disappearing Number, a visually powerful account of the lives and ecstasies of mathematicians, De Quincey Co’s Triptych, a large scale Body Weather reverie, and The Border Project’s Rock’n’Roll Disaster, a modest, but convincing fantastical foray into the consuming power of popular music.

In his little book, On Ecstasy (Melbourne University Publishing, 2008), Barrie Kosky amiably and vividly traces his emerging sense of ecstasy from the pleasures of his grandmother’s chicken soup to incipient homoerotic compulsion (the wet jeans of a TV character, the smells of the sports changing room), to the touch of fur (Narnia fantasies) and silk (in his father’s fur factory), to the first strange encounter with the soprano voice in Puccini’s Madam Butterfly (on his grandmother’s old records, prior to a first visit to the opera) and his bedroom conducting of Mahler’s First Symphony. He moves on to the realisation of ecstatic states in his early work, The Dybbuk, and recently in Europe with Euripides’ Medea, Ligeti’s Le Grande Macabre (with a flood of excrement: “What has taste to do with the theatre?”) and Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman.

Ecstasy in Kosky’s book is no simple feeling of elation, of well-being, of blessedness. It’s beyond wonder. It’s all consuming. It takes over the body. He recalls from the changing room of his schoolboy years, “Body odour of every imaginable flavour, sweat, socks, Dencorub, hot water, cheap soap, the wet old wood of the lockers. All clashing in my nostrils, all fighting to get up my nasal cavities. Whirling in my nostrils like a thousand miniature tornadoes. Sometimes it became so overwhelming I really thought that I was going to faint, or vomit or scream.” At 16 he sees Leonard Bernstein conducting Mahler’s Second Symphony, leading the orchestra, but danced by the music it makes, sweat spraying from his face. He is struck, it seems, by this intertwining of creation and possession.

The power of ecstasy, Kosky realises, is in its totality. At 15 he listens to Mahler’s First Symphony and asks, “What sort of composer puts a funeral march to a children’s nursery song and a zippy village klezmer band on the same page of a symphonic score? This music seduced me. It took me, convulsed me and drowned me. It suffocated me. It was gorgeous, repellent, terrifying. It scared the shit out of me. It still does.” He cites Mahler’s own words, “A symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything.” It’s not surprising then that Kosky’s productions are singular totalities, possessed and possessing, full of odd but integrated juxtapositions, full of beauty but equally revelling in the abject until it too is bizarrely glorious. He writes, “The theatre seems to me the perfect place for the ecstatic to manifest itself. Theatre is by its very nature an alchemical mix of manipulation, ritual and stimulation.” Ecstatic theatre is therefore beyond taste, self control and reason; it is violent and excessive, and “is best conveyed through phantasmagoria” where there is constant hallucinatory slippage between real and unreal. The worlds Kosky and his collaborators conjure are fantastical, not immediately recognisable as our own, but soon enough tellingly so. They are states to be entered into, endured and embraced, to become one with.

Robyn Nevin, Jennifer Vuletic, Natalie Gamsu, Queenie van de Zandt, Kyle Rowling,; The Women of Troy

photo Tracey Schramm

Robyn Nevin, Jennifer Vuletic, Natalie Gamsu, Queenie van de Zandt, Kyle Rowling,; The Women of Troy

The version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women (415 BC) that Kosky and Tom Wright created for the Sydney Theatre Company and Malthouse is not a work to which the word ecstatic might easily be ascribed, but the intense, sustained sense of grieving and despair it achieves amidst the horrors of the aftermath of war is relentlessy realised and exhaustingly compelling. And it is beautiful, in the most uncomfortable of ways, because the expression of grief yields great beauty, in and through music and acting—in a play that does not offer conventional character development but immediately demands extreme emotional states. Intensifying the focus on the women, Robyn Nevin (playing the Queen of Troy, Hecuba) and Melita Jurisic (as Cassandra, Andromache and Helen of Troy in turn), Kosky and Wright have removed the gods who open the play, Talthybius (the Greek army’s herald), and the words of the chorus (whom Euripides had cast as fellow victims of the war, singing of their individual and collective plights). Kosky’s battered chorus (Natalie Gamsu, Jenny Vuletic, Queenie van de Zandt) performs arias and laments (by Dowland, Gesualdo, Mozart, Bizet, Slovenian folk songs) sometimes joined by Nevin and Jurisic. The war with Greece lost, the women will become the slaves and spouses of the victors. The Greek King Menelaus (Arthur Dignam) arrives, in a wheelchair, to be seduced again, perhaps, by the wife who left him, triggering the war. Finally, a small boy, Astyanax, son of Andromache and Hector, grandson of Hecuba, and regarded by the Greeks as a potentially dangerous heir of Troy, is taken away, thrown off a cliff and his bloody body returned to the stage, in a small cardboard box, the legs visible only from the knee down, hanging limply from the opening. Euripides’ text is pared back, with brutal effect, but remains true to the intense feeling and musicality of the original if recast as modern music theatre.

This Kosky production is not a phantasmagoria, nor does Euripides’ play offer itself as one. It’s not like his recent The Lost Echo for STC or, earlier, Berg’s opera Wozzeck for Opera Australia. Its kin are the dark, closed worlds of the Ted Hughes/Seneca Oedipus and O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Elektra (both for STC), Kosky at his most restrained. And while The Women of Troy contains much of the world—poetry, blood, vomit, violence, song, opera, mobile phones, television (offstage), pianist (effectively onstage)—it’s an ecstatic vision shorn of display, sensuality, revelry and dance. Even the masked workers who beat, threaten and photograph the women against a vast wall of tired lockers (like some last ditch barricade that the tired walls of Troy have become) display none of the participatory glee of their kindred Abu Ghraib torturers. These guards are characterless, bureaucratic, delivering their captives on trolleys, removing the principal women one at a time in large cardboard boxes secured with the screech of packing tape—humans ritually reduced to freight. The drab ordinariness of the place, the loudspeaker announcements, the plodding entrances and exits of the guards suggest the banality of the evils perpetrated, appalling in their tedium and suspense.

And while grieving in word and song is powerful and beautiful and momentarily consoling, there is no way out for these women, however much they implore, challenge or doubt the gods, or attribute blame and pick at the wounds that are their tales, however fair and rational their pleas for compassion. They are trapped in the irrationality of vengeance, where violence is a constant. And so are we, our seats draped in white cloth, as if the theatre has been closed for the duration of the war, random explosions regularly triggered behind and below us. The bruised and bloody women are physically close to us in the small theatre, their fear, panic and despair inescapable as they cringe and cluster defensively, hide in lockers, confront and comfort each other in song.

Robyn Nevin as Hecuba, former queen of Troy, is the production’s anchor, defiant, elegant if battered, a rhetorician, visibly quivering as she keeps emotional and physical collapse barely at bay—her husband has been murdered, her daughters raped or killed and her grandson executed. Melita Jurisic, in her three roles is equally superb, not least as the play’s most frightening figure—the prophetess Cassandra, bedraggled, blind, bloody and vomiting—after spitting out a madly ironic celebration of her betrothal to King Agamemnon—then eerily rational and set on vengeance. Then she’s the sad, pregnant Andromache, and finally, the obtuse, devious Helen. The ‘agon’ of classical Greek tragedy is played out powerfully between Hecuba and Helen, but there can be no winning this argument.

The Women of Troy is deeply horrifying and deeply satisfying theatre. In the short term you are left without words—there’s a kind of numbness as you leave—later they flood out. The Women of Troy is another stage in Barrie Kosky’s making of an ecstastic theatre, there’s a whole world in it, recognisably our own, it goes beyond words, makes barely consoling beauty out of despair, plays out the contradictions of life and of art, tossing you about in the turmoil.

complicité: a disappearing number

Mathematics can yield its ecstasies and eureka moments and there’s much talk of its pleasures in Complicité’s A Disappearing Number. We’re entertained and surprised by some maths magic in the mock lecture opening, later calculations unfold as if by an unseen hand on a blackboard-cum-screen and later again flood the stage like stars in a symbolic universe. There’s a lot of theatre magic in A Disappearing Number, but the effect is less than ecstatic. It’s a play dressed up with effects, the actors belting out their lines as if forgetting they’re wearing head-mikes, playing out the didactic juxtaposition of two sets of lives—two male mathematicians (British and Indian) in the 1910-20s, and a female mathematician and her non-mathematician husband (British and American of Indian descent respectively). The parallels between the pairs are tentatively drawn, not least because writer-director Simon McBurney and his co-devisors have very little to say about the relationship between the two men and too much about the modern fictional relationship; its elaborated tensions seem very slight indeed and then melodramatic.

The set is an immaculately realised modern university lecture theatre: the whiteboard rolls over into a blackboard, becomes a screen backdrop (for mimed Mumbai taxi rides etc), or a screen for an overhead projector, or can fly in and out as desired, as does the whole wall to reveal rooms in England and India using back projections and a little furniture.

Complicité (formerly Theatre de Complicité who impressed Australian audiences on earlier visits with The Three Lives of Lucie Cabrol and The Street of Crocodiles over a decade ago) is a British company that combines the poetic and visual attributes of European contemporary performance with a dogged English literalness. Visually A Disappearing Number is a finely wrought, often beautiful spectacle about a brilliant self-taught Indian mathematician, Ramanujan, who overcame the constraints of his Brahmin code so he could visit his mentor GH Hardy in Cambridge. Harding recognised the Indian’s genius, seeing he would revolutionise mathematics. The pair became intimates, possibly in love with each other, although this is only hinted at briefly. Why McBurney couldn’t have at least speculated further is a mystery. There’s little we can learn from comparing the two relationships, save something about the cultural divide between England and India, which is barely evident in the modern male, Paul (raised in the USA), and which is oddly expressed in both he and Harding losing their partners to India—Ruth dies while on a pilgrimage to Ramanujan’s home where he had died shortly after returning, decades before. (She’s doubly punished—with a miscarriage prior to the trip.) When Paul finally goes to the India he’s never visited before, the parallels and synchronicities between couples and eras are then made to add up to a consoling metaphysic based on the continuity between the fictions we call numbers and a corresponding indivisibility between past and future, which means we are never really separated from those we have lost. The effect, with its immersive visual correlatives, was curiously consoling, but sentimental in retrospect. Nitin Sawney’s original score is partly played live and there’s a too brief passage of Indian dance, but these are incidentals in what could have been a greater more embracing dance of notes, bodies and symbols.

Peter Fraser, Triptych, De Quincy Co

photo Mayu Kanamori

Peter Fraser, Triptych, De Quincy Co

de quincey co: triptych

In her own work and with her company, Tess de Quincey, generates for audiences states of being that are hard to label. The performers move with a mix of eloquent grace and involuntary quivering, but are they dancing? They appear to see, to respond, but to what? Things we can’t see—remembered, re-lived, conjured? They don’t speak, but what are they signalling? Somehow, the intensity of their sheer otherness transmits itself to the bodies of the audience who then share a sense of contemplation, of reverie and risk as performers find themselves in positions that consume them but demand balance and then its loss and release before another or the same state again takes them. I’m often utterly at one with de Quincey’s creations, but not with Triptych. Here is a work with all the appearances of an embracing totality: the three large passages of the title, themes of air (projected images of the windswept dance of jacaranda flowers), electricity (a pulsing oscilloscope) and water (a somnolent ocean), four dancers, the uniformity of designer jeans and tops beneath kimonos, the music of Chris Abrahams throughout, and large scale projections in each scene on three mobile screens whose repositioning moves the audience about the performing space (variously opening up or shutting down perspectives).

But appearances are deceptive and although the performers enter their various states with all the commitment and precision you’d expect, the outcome is a collection of solos, occasional duets (Victoria Hunt and Linda Luke working in taut parallels in one passage against Robin Fox’s dancing oscilloscopery and Abrahams Fox-ish score), and all too rare moments of communality. Once I’d made a rational decision not to be distracted by the illusion of totality, the scale of the projections or the volume of the music, or taking too many performers in at once, I could focus on the pleasures and tensions realised in individual performances—Peter Fraser’s querulous self-interrogation, awed, erect, then crawling; Linda Luke’s rough-hewn assertions of and delight in risk; Lizzie Thompson, a fine dancer, here tremulous, unformed as yet in the world of Body Weather; Victoria Hunt’s muscular interiority with its long-held, acutely shaped tensions in the final scene. For me, at its best Triptych provided a kind of un-anchored shamanism, a performance of momentary pleasures and interrupted reveries. For others, it was ecstasy.

Highway Rock’n’Roll Disaster, The Border Project

the border project: highway rock’n’roll disaster

Highway Rock’n’Roll Disaster is a work of modest scale but one with a potent cumulative impact. It’s concert-like music theatre rooted in the everyday, in the love of popular songs that provide both escape (a loosening of voice and body that is both visceral and aetherial) and reflection (what was I feeling, thinking, doing, when I first heard that song?). The performance moves from mundane introductions to the songs to immersive performances, often against inventive video clips projected on the back wall or onto very mobile screens. The clips have their own integrity, or parody their inspirers, or provide an unexpected dimension: in one, a woman, not singing, stands in front of a screen on which a semi-literal drama is acted out, suggesting the death and perhaps heavenly ascent of one of the participants, like a movie version of a Duane Michaels’ photographic series about death and grieving.

The performers mutate from solo singers and instrumentalists into multi-skilled band members while their roadies turn dancers. And the songs too (Guns N’ Roses’ Sweet Child of mine aside) are mutant: they are the performers’ own, inspired by the originals that live in their psyches and bodies. It’s an odd alchemy, but the songs work and the performances are idiosyncratic and as the the performance moves towards its conclusion the concert world staging mutates again, into something much stranger: a delirious, dark world of bizarre giant creatures roaming amidst the musicians, a phantasmagoria, beyond words, of course.

Sydney Theatre Company, The Women of Troy, by Euripides, adaptation Barrie Kosky, Tom Wright, performers Robyn Nevin, Melita Jurisic, Natalie Gamsu, Jennifer Vuletic, Queenie van de Zandt, Arthur Dignam, Kyle Rowling, Patricia Cotter, Nicholas Bakopoulos-Cooke, Narek Armaganian,musical director Barrie Kosky, pianist Daryl Wallis, design Alice Babidge, lighting Damien Cooper, sound design David Gilfillan, Wharf 1, Sydney, opened Sept 20; Complcité, A Disappearing Number, conceived & directed by Simon McBurney with the company, design Michael Levine, lighting Paul Anderson, sound Christopher Shutt, projection Sven Oriel for mesmer, Sydney Theatre, Nov 12-Dec 2; De Quincey Co, Triptych, concept, direction Tess de Quincey, performers Peter Fraser, Victoria Hunt, Linda Luke, Lizzie Thompson, composer Chris Abrahams, audio-visual production Sam James, oscilloscope Robin Fox, lighting Travis Hodgson, Performance Space, Nov 6-15; Sydney Theatre Company, The Border Project, Highway Rock’n’Roll Disaster, performed, conceived, created and composed by the company, Katherine Fyffe, Cameron Goodall, David Heinrich, Jude Henshall, Andrew Howard, Paul Reichstein, Andrew Russ, Alirio Zavarce, roadies Danel Koerner, Tim Kurylowicz, Luca James Lee, Lachlan Mantelll, Kurt Murray, director Sam Haren, lighting Geoff Cobham, animation Jole van der Knaap, Paul Lawrence-Jennings, costumes Area 101, Wharf 2, Sept 19-27

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 42