arts business practice or practice based research?

peter anderson: artstart, era and the visual arts

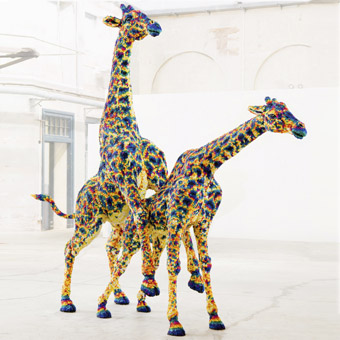

Belle Brooks, University of Sydney, Typing “Giraffe Sex” into Google Yields Ungodly Results 2008

Hatched 2009 National Graduate Show

Belle Brooks, University of Sydney, Typing “Giraffe Sex” into Google Yields Ungodly Results 2008

FOR MANY YEARS THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL’S GRANT GUIDELINES INCLUDED A LONG LIST OF THINGS THAT THEY WOULD NOT FUND. THEY STILL DO, BUT NOW THE LIST IS A LITTLE SHORTER. WHILE FUNDING IS STILL NOT GENERALLY AVAILABLE FOR THE ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OF UNDERGRADUATE AND POST-GRADUATE STUDENTS, ONE OF THE THINGS THAT HAS DROPPED OFF THE LIST IS THE EXPLICIT EXCLUSION OF ‘ACADEMIC RESEARCH.’ THIS IS, PERHAPS, A RECOGNITION THAT A GOOD DEAL OF ART PRACTICE THESE DAYS FUNCTIONS WITHIN A RESEARCH PARADIGM, WITH QUITE A LOT OF IT GOING ON IN AND AROUND ART SCHOOLS THAT ARE NOW EMBEDDED WITHIN THE UNIVERSITY SECTOR.

It’s part of a shift that has been going on for a couple of decades, along with the gradual expansion of research based higher degrees in the visual arts. Accompanying this has been the long on-going debate around the treatment of art practice as a form of academic research, which has entered a new stage with the initial trials of the new Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) framework.

But something else has also happened over the last decade, perhaps producing a quite different practice paradigm. Since the introduction of the GST and related tax reforms, artists have been increasingly obliged to function explicitly as small businesses. In this context, art has to pay its way: it’s a business activity as much as a purely creative, critical or research activity. And while bodies like the Australia Council used to expect artists to have a few years practice under their belts before they applied for funding, support is now increasingly being directed at the emerging artist immediately following the completion of an undergraduate degree.

artstart

The recently announced ArtStart program falls broadly within this model, adding a further $9.6 million over four years to the more than $6 million allocated last year for emerging artist programs. As the Arts Minister’s press release of May 12 2009 put it, ArtStart “offers one-off grants to help graduates start a business as professional artists.” At the time of writing the detail of the grant conditions remains unresolved, but the program—to be administered by the Australia Council—will be offering grants of up to $10,000 to emerging artists under 30. While the ArtStart policy had originally been linked to the issue of artists on welfare, the announcement of the program focussed attention on the fact that “many emerging artists are forced to rely on their own resources and part-time jobs to subsidise their careers.”

ArtStart has generally been welcomed within the visual arts community, but there are concerns about its capacity to deliver. As the Chair of ACUADS and Head of the University of Tasmania’s School of Art, Professor Noel Frankham, puts it, “I doubt very much that $10,000, useful as it would be, is going to achieve the goals articulated for the program—assuming tax exemption, I estimate that it would buy rental of studio space for a year, but an artist still has to pay home rental, buy food, and art materials.” In this respect, it is worth noting that the cross-subsidisation of artists’ practices is not restricted to emerging artists, with the 2003 report on artists’ working lives, “Don’t Give Up Your Day Job”, indicating that over 60% of professional practicing artists work additional jobs, many of them in teaching.

a career: when?

In the light of this, Associate Professor Donal Fitzpatrick Head of Art & Design at Curtin University in Western Australia notes that while “any financial support would be welcome, it has to be thought through in relation to needs.” How, for example, does ArtStart compare to venture capital models that operate in other areas of the creative industries? And what about the increasing numbers of artists with higher degrees, how do they fit the policy framework? As Fitzpatrick sees it, with the increasing focus on practice based research degrees “there needs to be more consideration of the development of career paths in the pivotal couple of years after art college.”

This is an issue that also concerns Noel Frankham. “A program that focuses on graduating students under 30 is likely to miss many of the most serious, talented and worthy new graduates”, he says. “Increasingly, those with a serious commitment to establishing a viable professional art practice are undertaking research masters and doctoral programs (often both), meaning that they are highly likely to be over 30 when they embark on exhibition careers.” This introduces a further, and perhaps less palatable problem, which relates to the issue of career outcomes for undergraduates. As Frankham notes, “whilst investment in bachelor degree graduates is likely to be useful, it is less likely to be an investment in long term practice as artists, as most bachelor degree graduates from art schools do not apply their qualifications and skills to earning their income from creative arts practice; they use their degrees well, but not as artists.”

era: creativity as research

With regard to ArtStart and the Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) project, Noel Frankham cautions against “making too direct links between programs for measuring the quality of academic research in the creative arts (ERA), and those aimed at supporting professional practice (ArtStart).” They are, he says, “complementary but un-related.” However, a tension remains, not least because of the lack of distinction between academic and professional arts activities, with ERA now counting artists’ exhibitions, curated projects and exhibition catalogues as valid research outcomes within the university system.

This is a very significant development for those artists who work in academic institutions, as well as for the schools and departments in which they are employed. As Donal Fitzpatrick puts it, the creative arts were previously “viewed as an afterthought, something that you add on to the broader sweep of academic work and research which was done elsewhere in the university.” But the new framework of ERA changes this, treating creative work as part of the research output of art schools, having an impact on funding, and “our status within the university”, says Fitzpatrick. “From my perspective there is much to be gained from normalising creative outputs as research within universities and the culture more broadly”, he says.

One strand of this new development is the increasing significance of the ‘practice based’ research higher degree, the impact it might have on how art practice is understood and the role it might play in artists’ career development. Another is the significant shift in how the new research framework treats issues such as peer review and ‘publication.’

peer review before or after the event?

How will the existing visual arts infrastructure play a role—from art magazines to art galleries, not to mention existing funding agencies (like the Australia Council)? As Su Baker of the Victorian College of the Arts notes, “we see peer review at many levels within the artworld, but this hasn’t been well understood at ARC (Australian Research Council) level.” At the same time, “there have been mixed messages regarding the issue of counting Australia Council grants as research outputs.” Similar issues may also emerge around how exhibitions in different gallery contexts are treated, or more particularly how decisions are made regarding the selection of work for exhibition. As Donal Fitzpatrick notes, one key issue is ERA’s shift in focus “from peer esteem to quality assurance.” “In the case of the visual arts this means that what comes prior to the ‘event’ (exhibition for example) becomes of paramount importance and what comes after is much less so…This is a massive shift for creatives to get their heads around”, he says. “All of their career paths till now have been driven by a review culture of endorsement that comes after the event, not the (peer review or selection) processes before the event.”

What this difference highlights is the structural change that a research based visual art practice may generate, with academic artistic advancement being based on peer decision making within the academy, irrespective of the response of critics, curators, or the market. While the implementation of ERA is seen primarily as an issue for artists working in academic institutions, it does have potential implications for the sector as a whole. While it is important for artists working as academics to have their work properly valued within the university context, we also need to carefully examine how this might impact on other aspects of the artworld. As we already know, there is no neat and easily identifiable relationship between critical and commercial success. In light of this we might also consider the possibility that significant academic achievement may not provide a ready framework for the establishment of the sort of viable arts business that programs like ArtStart aim to support.

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 4