the poetry of the mundane

sandy edwards: japanese photography, 1970s to the present

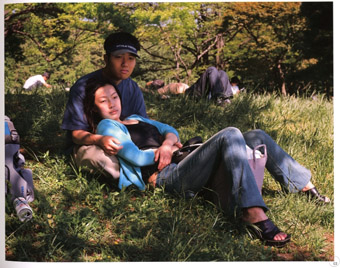

From the series Picnic, 2004, Masato Seto

courtesy the artist and the Japan Foundation

From the series Picnic, 2004, Masato Seto

Gazing at the Contemporary World, at the Japan Foundation Gallery, Sydney, is the sort of exhibition you would expect to see at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Praise must go to the Japan Foundation for bringing it to Australia. I cannot think of another survey exhibition of Japanese contemporary photography shown here in recent years. Unfortunately it’s on display for only two weeks, for there is much to learn from it.

The exhibition, curated by Rei Masuda, Curator National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, is divided into two sections, one titled A Changing Society and the other Changing Landscapes. It contains 76 photographs from 23 photographers, some well known, many not. David Freeman, the Japan Foundation’s Coordinator for Arts & Culture, says the exhibition is attracting audiences because of the subject matter as opposed to the reputation of the artists.

On first impression the works appear quiet and understated. The photographers, whose approaches are quite diverse, seem to be whispering rather than shouting. They ask for a steadiness of gaze and an attentive mind.

To outsiders, Japan has always been tinged with exotic difference. But Gazing at the Contemporary World could not be further from exotic. Instead, it focuses on the mundane in everyday life. The infamous Japanese photographer of the erotic, Nobuyoshi Araki has asked, “Why photograph the totally ordinary everyday stuff when nothing is actually happening out there?” But in Gazing at the Contemporary World, what could be more mundane than to document the outside and inside of refrigerators? In his series Ice Box (1988), Tokuko Ushioda presents two pairs of photographs of refrigerators, which provoke contemplation about their very different owners’ lives.

Documentary forms predominate. To an Australian viewer, however, there is a poetic, perhaps spiritual, overlay that is not common in western photography. In his photograph Tokyo, from the series Nihon Mura (‘Japan Village’, 1979), Shuji Yamada portrays the city as a dark moonscape with a topsy-turvy skyline broken up by peremptory, jagged high-rise buildings. The only sign of light is that reflected by the roofs of buildings.

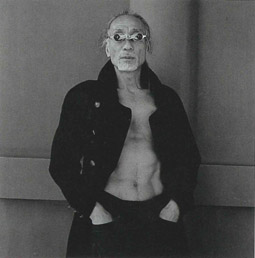

There is a distinct air of sadness and a sense of distance from the world pervading the images in Gazing at the Contemporary World. Perhaps it is the observational gaze Rei Masuda refers to in the exhibition title. Likewise, in some portraits by Hiroh Kikai, from the series Persona, the characters portrayed appear strangely unhappy in their presentation to the camera.

A performer of Butoh dance from the series Persona, Hiroh Kikai 2001

courtesy the artist and the Japan Foundation

A performer of Butoh dance from the series Persona, Hiroh Kikai 2001

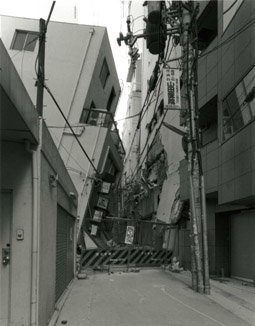

The landscape is depicted as scarred and (mostly) devoid of human presence, sometimes due to industrial ‘advancement’: for instance, in Toshio Shibata’s two images from the series Quintessence of Japan (1989) and Norio Kobayashi’s poignant image of a large dead dog, revealed in the landscape after snow has melted, from Suburbs of Tokyo (1984). The ambitions of failed human endeavour are documented in the construction of high-rise buildings and bridges, particularly in Toshimi Kamiya’s unfinished bridge going nowhere, from the series Mirabilitas Tokyo (1987), and in Hitoshi Tsukiji’s impressions of looming concrete structures overwhelming any human scale in Urban Perspectives (1987–89).

Two series provide drama and emotional release. Masato Seto’s richly coloured Picnic (2004), portrays couples seated and lying in parks with an intimacy of contact not found in other images. Ryuji Miyamoto’s extraordinary photographs of Kobe after the Earthquake (1995) have vivid impact in their depiction of buildings and whole streets collapsed from the force of the disaster. These images speak metaphorically, in a way others do not, of the enormity of change Japan has been subjected to in recent times.

Sannomiya, Chuo-ku, from the series Kobe 1995 After the Earthquake, Ryuji Miyamoto

courtesy the artist and the Japan Foundation

Sannomiya, Chuo-ku, from the series Kobe 1995 After the Earthquake, Ryuji Miyamoto

In his essay, curator Rei Masuda details the important events in the history of photography in Japan at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s that brought about the rise of ‘konpora’ (which translates roughly as ‘contemporary’) photography. Gazing at the Contemporary World sheds light on the many trends in and influences on Australian photography over the same period. These comparable yet culturally very different histories could benefit from greater examination.

Gazing at the Contemporary World: Japanese Photography From the 1970s to the Present, Japan Foundation Gallery, Sydney Feb 22-March 5 2010

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg.