expanded dramaturgical thinking

jonathan w marshall: dramaturgies #4

Workshop notes Dramaturgies #4

FEBRUARY SAW THE 4TH DRAMATURGIES SEMINAR ORGANISED BY MELANIE BEDDIE, PETER ECKERSALL AND PAUL MONAGHAN. PREVIOUS MEETINGS FOCUSSED ON THE ONLY PARTIALLY RESOLVED DEFINITION OF 'DRAMATURGY,' ON DRAMATURGY AS A CRITICAL AND POLITICAL PROJECT (“INTERVENTIONIST DRAMATURGY” IN ECKERSALL’S WORDS), AS WELL AS PRACTICAL STRATEGIES FOR WORKING IN A DRAMATURGICAL MANNER.

There were three working parties for Dramaturgies #4: Collaboration facilitated by Eckersall, Diversity by Beddie and Training and Research (the group I joined) by Monaghan. John Romeril noted of Dramaturgies #3 that it had an “experiential emphasis.” with a “learn by doing and observing approach”, problems being addressed “on the floor” and on one’s feet. The decision of Eckersall’s group to present their findings in the form of a space strewn with snaking passages of text, balls of paper, objects, and scenographically arranged mess, reminiscent of artist Joseph Beuys’ perfomative lectures for the Free International University, represented an attempt to blend experiential knowledge (the body, performance, space) with theory and ideas.

Overall though, Dramaturgies #4 took the form of oral discussion. With Richard Murphet playing a prominent role, at times it seemed a festschrift for the former head of VCA Theatre. Murphet’s engrossing keynote reminded us of links between contemporary understandings of theatrical structure and Euro-American developments, as well our indebtedness to the experimental, often nationally-focused, work of the Australian Performing Group and the Pram Factory. Murphet attended US director and theorist Richard Schechner’s infamous production Dionysius in 69, which The Australian characterized as “the ultimate 1960s group-grope show.” Schechner’s ideas on the transcendence of the mundane through staged interactions, in which text, image, design and the body all played a significant role, and which were widely dispersed about a multi-focal theatrical space, helped set the tone not only for much of the material produced by artists like Murphet, but incited Australian practitioners to wrestle with articles on Artaud and Brecht from Schechner’s journal, TDR. Thinking dramaturgically has a long history in Australia, running from Eugenio Barba’s influential appearance in The Drama Review [TDR] through to Murphet’s production of The Inhabited Man (2008; see RT 87, p8).

The working parties at Dramaturgies #4 struggled to find common ground, leading to some “group envy.” In closing presentations, many of the Diversity panel contended that the matter is best addressed as an integral concept, enmeshed within every aspect of theatrical thinking, rather than treating it separately, whilst we in Pedagogy wrestled with how to approach so broad a question as the teaching of the full variety of practices involved in the structuring of theatrical knowledge.

Literary issues of editing, textual analysis, and May-Brit Akerholt’s wonderful keynote on script translation, loomed large, but we broadly agreed that the task was to assist students, artists and the public to “think dramaturgically”—rather than necessarily to become that strange beast, the “company dramaturg,” who is typically yoked to the text. Dramaturgy was seen as a way to think in terms of the structures and tendencies involving space, text, sound, light, time, politics and so on (Barba’s weft or “weave”), all of which are measured, invoked and manipulated within the theatrical scene—and within many social and historical arenas as well.

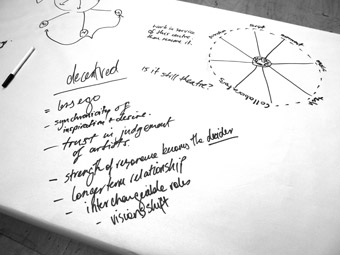

After much to-ing and fro-ing, Murphet offered a possible systematisation of certain critical aspects of a dramaturgical consciousness, which I gloss below. Universal agreement was never to arise, and I felt there was a reluctance by many to confess how our own constructions of dramaturgical practice were weighted towards post-1960s “performance” and the kinds of neo-avant-garde theatre promoted by Schechner and his successors. Dramaturgies #4 was not just notable for its stellar list of delegates, but also for those not present. Where was MTC, the Australian Ballet, Bell Shakespeare, the Australian Writers’ Guild and other institutions many of us characterise as relatively “conservative”? Eckersall’s proposed “‘national audit’ of dramaturgical practices in and for the sector” could not be fully effected here.

The circle Dramaturgies #4

Dramaturgies #4 rather reflected a partisan (though internally divided) set of proposals for thinking about how theatre is put together and how it relates to the wider world, whereby certain aspects of avant-garde praxis and ideals of social or aesthetic intervention—however modest in form, even if only focused on changing perception rather than political structures per se—would be espoused. Whilst dramatically inflected work was the dominant subject of discussion, dance theatre and at least some forms of performance art could be accommodated by the proposed models and membership. Nevertheless, dramaturgy as a potentially totalising socio-aesthetic critique, as a way of modelling the wider social 'ecology' of theatrical ways of acting and describing phenomena—be these on stage, in the visual arts, in political and social action, of socio-cultural occurrences varying from war to shopping—remains an unexplored challenge.

To think dramaturgically, one must learn how to read a piece of theatre; which I would see as rendering all dramaturgs critics. Secondly, it was agreed that one must have a broad knowledge of all aspects of theatrical practice and construction, running from choreography to lighting, text and so on (there was some debate as to whether one should learn such ideas “from the inside” by doing, or, as in my own teaching, through “outside” analysis). One must be able to think of theatrical composition in terms of its formal elements. Phrases such as “the performance score” were deemed helpful, as were models from music (harmony and dissonance), literature (Homeric structures, the Epic, Aristotelian tragedy, Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of “making strange” or defamiliarisation and so on), visual arts (balance and composition), plastic arts (texture, weight, mass) and—especially as far as my own teaching is concerned—the multidisciplinary pedagogy of director Oscar Schlemmer, architect Walter Gropius, painter Wassily Kandinsky, composers Paul Hindemith and others at the Bauhaus School in the 1920s.

Ian Maxwell from Performance Studies at University of Sydney observed that dramaturgs must know how to “break the hermeneutic circle of the work”, or in Murphet’s terms, to disabuse those “expectations” which the structural rules listed above might impose. Barba and Eckersall have used the terms “turbulence” and “con-fusion” to suggest a similar interplay of order and a deconstruction of that order within dramaturgy. This could involve, for example, sudden transitions from tragedy to farce, or vexing a progression from light to darkness.

Monaghan began with the suggestion that a dramaturg is one who “imagines his or her audience”. Such a generalised concept is broad enough to encompass works where the aim is to challenge and provoke, as well as more humanist ideas of the performing arts as entertainment, as describing one’s own life (drawing-room comedy, for example) and other forms of practice.

Finally, one concept which I would contend is essential to all considerations of art, is an awareness that any and all forms of dramaturgy contain within them a “worldview.” The dramaturg must take seriously ideas about philosophy, politics, the body, religion, ritual, anthropology, race, gender, sexuality and other matters as they pertain to the work and to the world as a whole. To craft a theatrical space is to model the world, society and the cosmos—the theatrum mundi or little theatre of the world which Renaissance scholars extolled. Dramaturgical perspectives have the potential to provide a totalising “gesamtkunstwerk” of culture itself, of politics, the arts and of our relation to these phenomena.

Whilst Dramaturgies #4 did not reach any final agreement on how to impart such a way of conceiving knowledge and experience, let alone what limits to such concepts we might want to impose and under what circumstances, Eckersall, Monaghan and Beddie provided a challenging forum wherein such ideas could be debated. If the only outcome of Dramaturgies #4 was to allow us to listen to theatre-maker and Director of The Centre of Performance Research (UK) Richard Gough’s celebration of the cultural and affective density of objects, then it was worthwhile. Gough confessed that, like many other dramaturgs, he was “drawn to objects that…emerge into daylight from dusty attics, mouldy sheds, damp garages and…junk shops…I liked the patina…the scars and markings of an object well used, of functionality and distress; objects abandoned, discarded, rejected and forlorn.”

Such Duchampian detritus has an already established life of theatrical processes and history, which is waiting to be invoked within new theatrical environments, from the cabinet of curiosities to the stage. Having heard that one of Australia’s most successful dramaturgs, Michael Kantor, announce to delegates he is leaving theatre to take up a more environmentally proactive life, Gough’s words about cherishing of the worn textures of embodied refuse, and of the performative weight locked within otherwise derelict objects, suggested that the full ecology of dramaturgy continues to need careful and sensitive husbandry.

Dramaturgies #4, convenors Melanie Beddie, Peter Eckersall & Paul Monaghan; Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne University, Feb. 17-20.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web