culture: an intangible, protectable & nurturable good

jana perkovic: cultural policy and the arts

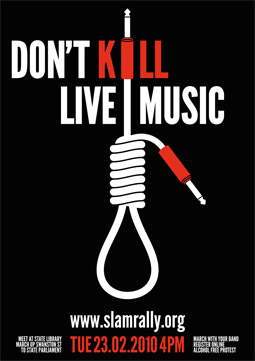

Save Live Music in Melbourne – a petition with 22,000 signatures calling for the the delinking of live music and “high risk” licencing conditions, delivered to the Victorian Government April 7

photo www.carbiewarbie.com, with thanks

Save Live Music in Melbourne – a petition with 22,000 signatures calling for the the delinking of live music and “high risk” licencing conditions, delivered to the Victorian Government April 7

IT IS A COMFORTING THOUGHT THAT AUSTRALIANS ARE GREAT AT ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND SMALL-SCALE INNOVATION, BUT LET ME SUGGEST WHAT WE DO EXTREMELY BADLY: LONG-TERM AND LARGE-SCALE STRATEGIC PLANNING. IF SUSPICION OF GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION IS RIFE, IT MUST BE BECAUSE WE HAVE VIRTUALLY NO EXAMPLES OF A WELL-THOUGHT-THROUGH, AMBITIOUS AND SUCCESSFUL STRATEGIC INTERVENTION. FOR EVERY INNOVATIVE ECO-BUILDING AND LANEWAY FESTIVAL, WE HAVE A FAILING PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK OR A FORGOTTEN CARBON EMISSIONS SCHEME.

One-person innovation has traditionally been the domain of artists—this is the thinking behind many a ‘creative industries’ policy. The corollary is that artists are perceived as situated outside large systems (ministries, policy frameworks) as subcultural rebels, creating on the geographical, economic and social margins, needing no infrastructural support for their ephemeral creations.

Yet, looking at Australian arts in urban terms, another picture emerges. My research finds almost every arts venue in Melbourne since 1991 clustering in loose clouds around public transport, state art centres and educational facilities, and moving around to avoid the worst of the real estate boom—in music, design and performing arts alike. It is tempting to attribute artistic success solely to individual genius, but there is in fact cultural infrastructure in place, which includes schools, low rents and central locations, on which every artist relies, and this infrastructure is what cultural policy can begin to protect.

the importance of breeding places

It is common in artspeak to talk about defunding artistically irrelevant institutions, as Gavin Findlay does (RT96, p8), but it is actually the uncertain funding of institutions that emerges as a bigger problem. For small- and medium-sized companies, flagship buildings to perform in and independent programming venues are a vital link to peers, critics and audiences. Convinced of art’s ephemerality, we forget the importance of ‘breeding places’: spaces and events that yield exposure, attract audiences, house archives, provide education and build social centres for the fleeting world of the arts. They serve their role best when their location and program times are unchanging and predictable—because then they can become meeting points, exchange points, networking points.

When we speak of the ‘independent’ artist, we sometimes forget how much artists depend on each other. Our few remaining theatre archives, the only memory-keepers we have, are tied to institutions with longevity (STC, Dancehouse, arts centres, state libraries); while VCA, Dancehouse or La Mama in Victoria, or Performance Space and TINA in NSW, are actual incubators of ‘scenes’ (social capital, an aesthetic, training), ensuring continuity to the arts. We can myopically boast a long list of important places and events that have ceased operating, from Pram Factory to the Green Mill dance festivals. Our lack of regard for ‘breeding places’ is best exemplified by the treatment of Performance Space, possibly the most important space for contemporary arts in Australia. A living incubator of innovation since the 1980s, having nurtured dozens of our most important performers, it has still not been recognised as a cultural flagship, let alone endowed with a permanent space of its own or operational autonomy within CarriageWorks.

The arts can and do punch back—but only if the issue can be sold in more than artistic terms. As I’m writing this, Victoria’s liquor licensing laws are being tweaked to save The Tote, a ramshackle music venue, from closure. Politicians were more worried about the voting preferences of the 200,000 protesters than the cultural significance of The Tote, granted; but the 200,000 saw The Tote as an indispensable part of Melbourne’s culture, not a den for a handful on society’s margins. However, this hasn’t come out of nowhere: at least since Espy, the iconic music pub in St Kilda, was threatened with closure in 1997, live music has been promoted as a key part of Melbourne’s ‘cultural’ specificity. Yet there must be a better way to protect cultural incubators than with rallies.

culture as a given

For many arts practitioners, the debate on the national cultural policy may look suspiciously like yet another thing to complicate already-fuzzy KPIs—but it would be unwise to limit the discussion to arts funding, because it is about more than that. To admit to a ‘culture’ is to say that there are things that we do that are important and worth protecting, because they make us who we are, regardless of their economic, health or social outcomes. In a sense it is irrelevant whether ‘culture’ includes media (as in Germany), is defined as “anything that stimulates closeness” (as in Croatia) or is left undefined (as in many European countries that nonetheless have robust cultural policies). It is primarily a principle of protection.

Artists should understand the power of words. At the moment, one of these is ‘economy.’ Being good or bad for the economy, vaguely defined, is argument enough to defend or shelve a policy. Agreeing that we have a ‘culture’ would allow a whole new string of arguments to be made and, with due respect to David Throsby, defend the arts not on the grounds of its goodness for the economy, community or health, but simply as important for our culture.

Of course, arts policy in Australia already assumes ‘culture’: funding of opera is otherwise inexplicable. But let me give you a sense of what else ‘culture’ might protect: in the 1990s Amsterdam initiated Broedplaats (“Breeding Places”), a squat protection policy, recognising them as incubators of creativity. “No Culture Without Subculture” was the mayor’s rallying cry. Formation of ‘alternative cultural centres’ is common throughout Europe, with a kind of light heritage overlay protecting use, rather than the form, of a building. Palach, in Croatia, has been an alternative music venue/gallery/café/performance space since 1968. It has had its dull phases, of course, but a new generation of bright young things inevitably emerged, taking over the same central location and benefiting from access to facilities, a ready-made audience and previous generations of artists. Similarly, the Save the Espy campaign in Melbourne could not rely on existing state laws to protect the beloved music pub: it didn’t qualify in terms of architectural, community or social heritage. After a prolonged fight, Espy was ultimately saved in 2003 because the local council managed to install sufficient protection on the grounds of local ‘cultural’ significance.

Save Live Music in Melbourne (SLAM) poster

cutting across policy areas

Another intervention that only national cultural policy can achieve is the nurturing of systems, interventions that cut across policy areas and require departmental collaboration on the federal level. Many have been picked up in the submissions to Peter Garrett’s cultural policy discussion website: simplification of artist work visas, greater support for regional and overseas touring (having no national culture, Australia has no sustained cultural diplomacy either). To this I would add improvements to arts education, understanding the importance of subcultures and integration of arts institutions into the urban fabric—giving them centrality, advertising, public transport. What was the point of investing millions in CarriageWorks, I wonder, if it is still sitting next to an underdeveloped train station, in a dark street, untouched by a single useful bus line? A comparatively cheap intervention into public transport would have quadrupled the returns on the enormous investment. Instead, one of Sydney’s most central performance venues manages to remain hidden to most of its population.

But what I would like to see most is some meaningful form of social security for artists. In most countries with ‘culture’, artists benefit from tax exemptions and reductions, access to free health insurance and pension funds, and different forms of income support that usually don’t require active job seeking. It is a measure that gives artists some modest existential certainties, but it’s also an intervention that the Australia Council for the Arts cannot initiate on its own.

art without culture…?

Judging from the way we mangle our strategic policies, there is no reason to assume Garrett’s national cultural policy will get everything right. But defining ‘culture’ as an intangible, but protectable and nurturable good is the first step towards building systems, structures and strategies that ensure longevity for what we’ve got. We need culture if we want to remember, and be remembered ourselves; if we want our art to matter. Without ‘culture’, we’d have no culture wars, true, but also no values, meaning, sense. Without culture, nothing differentiates the arts from any other unprofitable industry. And without culture, there is literally no subculture.

Jana Perkovic is working at the University of Melbourne on an ARC-funded research project titled “Planning the Creative City”, studying the geographical clustering of independent arts in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane, and the relationship between arts policy, demographics and urban planning. She writes for RealTime on contemporary dance and performance in Melbourne and Europe.

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 10