sao paulo: public space as theatre space

james brennan: three são paulo theatre companies

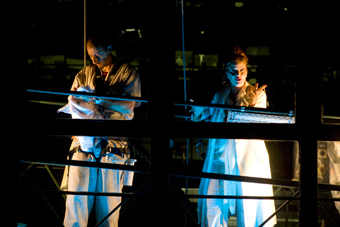

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

photo courtesy of Opovoempé

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

IN REALTIME 95 (“PERFORMANCE IN BRAZIL’S MEGA-METROPOLIS,” P42-43), CARLOS GOMES, A BRAZILIAN DIRECTOR BASED IN SYDNEY AND WORKING WITH THEATRE KANTANKA, REPORTED ON A RECENT VISIT TO SÃO PAULO, SURVEYING THE WAYS IN WHICH COMPANIES ARE ENGAGING WITH THEIR CITY, THEATRICALLY, POLITICALLY AND IN TERMS OF URBAN GEOGRAPHY. MELBOURNE ACTOR AND THEATRE MAKER JAMES BRENNAN RECENTLY VISITED THE CITY WHILE ON A KEITH AND ELISABETH MURDOCH TRAVELLING FELLOWSHIP. HE REPORTS HERE ON THE WORK OF THREE COMPANIES WHO CREATE WORKS IN WHICH THEY OCCUPY PUBLIC SPACE.

Whatever the country, theatre gives itself the mandate to claim space and to unravel that space in order to establish a relationship with those whom it seeks to make its public. I recently encountered three theatre companies in São Paulo, Brazil. What follows is an account of how each tackled public space, the audiences they found themselves ensconced with and the boundaries that marked their performances.

Compania Livre’s recent work was an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, performed over three nights in SESC Pompeia, one of many SESC cultural sites found throughout São Paulo state (Serviço Social de Comércio is a non-government cultural network established in 1946 by the industrial sector). The site has a theatre space, but instead director Cibele Forjaz chose a large empty studio, adjacent to the theatre which has changed little since its past life as a steel drum factory. As one of Brazil’s most successful contemporary theatre directors, Forjaz has always had an appetite for unusual spaces. With her reputation she has access to a wide range of theatre venues in São Paulo, but continues to search out unconventional sites in which to house her visions.

In discussing The Idiot she said, “We wanted a space that held scene and public in connection…moreover, we required that as the spectacle developed, action could occur concurrently in several spaces.” This was achieved through a design which supported a number of overlapping performance areas, able to transform quickly, in keeping with, as Forjaz puts it, “the subjectivity of each character.” The success of Compania Livre’s well-integrated performance environment can also be attributed to the actors themselves. Accompanied by a musician and a small technical crew, they ran, sang, hovered, danced, washed and prayed the space into ever-new formations. When the work required the actors to articulate somewhat stylised moments, this was achieved with a sense of ease, as if an extension of their social selves rather than heightened performance personas. Furthermore when invited, the audience participated comfortably, contributing to an atmosphere of permission. In a characteristically Brazilian moment, audience joined actors as they sang a well-loved bossa nova song during the moving climax. Tears rolled on and off stage and in that moment I was a firm believer in “freedom inspires freedom.”

Kastelo, Teatro da Vertigem

photo Angelo Lorenzetti

Kastelo, Teatro da Vertigem

Another company which chose to forego the conventional performance space offered at another SESC site is Teatro da Vertigem (RT95, p42). This time, the design and overall effect served to distance audience and performer. Given that the work was an adaptation of Kafka’s The Castle, Kastelo, this did not seem inappropriate, since the work is marked by an inherent sense of distance. Kastelo was exactly the sort of work I was hoping to see in São Paulo—risky site-specific.

Performed on the outside of the SESC building by actors on moving window-cleaning platforms, the work was viewed by an audience seated on swivel chairs scattered throughout a disused office space on the fourth level of the building. The obvious risks of performing while suspended on cables were further emphasised by the actors, who, with an uncanny absence of apprehension, would jump off their platforms and hang from their harnesses. As the work developed, there was an increasing amount of head banging against the glass, sometimes done by swinging from a distance, which resulted in one of the actors dangling, upside down and bloody for long periods. Eliciting moments of empathy, ultimately Teatro da Vertigem was unable to bridge the gap between audience and actors. Like the protagonist, we also struggled to achieve meaningful contact.

Hand in hand with its commitment to exploring alternative arenas in which to perform, Teatro da Vertigem’s work has a strong social aspect. The company’s director, Antonio Araujo, listed projects which have engaged with locations in cities and rural areas and inside and outside various institutions. Recently the company commenced work on a project in Cracolandia (“Crack Land”), an area avoided by many São Paulo residents due to the high crime rate and drug use. As a consequence the work has the potential to offer new perspectives on an area with a strong negative ambience, inbuilt and palpable. As with many of São Paulo’ contemporary theatre works, the project will involve a significant period of research in Cracolandia itself.

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

photo Ana Carmen Foschini

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

Opovoempé is a São Paulo theatre company whose agenda is focused directly on public space. Since its birth in 2005, the company has made a series of public interventions in locations including not just streets, fairs and squares, but also supermarkets, train stations and shop windows. Their works range from the overtly theatrical to the invisible, and draw on the legacy of cultural activism championed by the late Brazilian theatre maker, Augusto Boal. The company’s title (literally “people on their feet”) reflects its aims and “gives the idea of people moving, rather then riding or sitting. People in active existence or operation.”

The company states that their projects “aim to promote new relations between people and the space of the city, and are based in the exploration of the frontiers of the dramatic act.” With this premise they act to infiltrate chosen social settings to “subvert operating systems and alter the perception of participants.” Forty years ago such a statement may have made them a target for the Brazilian dictatorship, however these days their work resonates more as poetic provocation than political motivation and has received the support of the State Secretariat of Culture.

By offering new perspectives of shared space and interactions, Opovoempé illuminates the public lives of São Paulo residents and beyond. In doing so the company calls for vivid interaction with the spectator, to be “stimulated to perceive, see, imagine, interfere, create, act.” Such an active blurring of boundaries between art and life certainly fuels a fibrous artistic discourse and brings to mind the layered impact of Deborah Kelly and Jane McKernan?s powerful evocation of the Tiananmen Square protest, Tank Man Tango (RT93, p2-3).

With ever expanding public liability laws defining acceptable public activity, companies such as these three play an important role in questioning how we inhabit our environments and provide valuable stimulus for new perspectives.

I have always been intuitively committed to heightening the collision between theatre and life. Interacting with these companies in Brazil confirmed my belief in the critical need to deliberately exchange the space between the real world and theatre, in such a way as to confuse expectation. This may not only awaken the sleeper, but can also transform our cities and towns into places of social communion. By magnifying and directing performer ability to manipulate space, time and meaning, each of these companies illustrates the power of the individual to transform space and thought well beyond the walls of the theatre.

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web