tackling bio-art’s ethical ambiguities

urszula dawkins: symbiotica symposium, body/art/bioethics

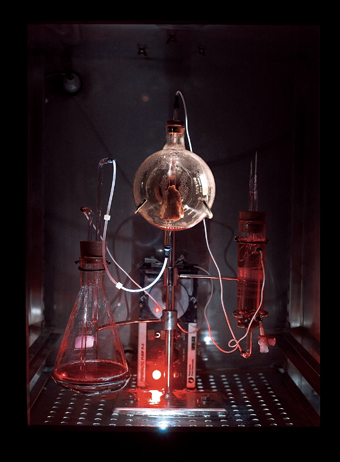

Victimless Leather, Ionat Zurr

courtesy the artist

Victimless Leather, Ionat Zurr

WA’S SYMBIOTICA—A KEY INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE BIOLOGICAL ARTS—IS NOW AROUND 10 YEARS OLD, TUCKED AWAY AND THRIVING IN UPSTAIRS LABS AND OFFICES BEHIND THE LEAVES AND SANDSTONE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA (UWA). IT RUNS A RANGE OF ACTIVITIES THAT STRETCH ART/BIOSCIENCE ENGAGEMENT TO ITS VISCERAL EDGES. ITS AUGUST SYMPOSIUM, BODY/ART/BIOETHICS, FOCUSED ON THE BODY—THE HUMAN-ANIMAL ‘FLESH-MACHINE’—WHILE ALLOWING SPACE FOR A BROAD RANGE OF TOPICS OF INTEREST TO INTERDISCIPLINARY BIO-ARTISTS.

In the absence, for personal reasons, of the first programmed speaker, biopolitics researcher Catherine Waldby, “renowned Australian writer” Elizabeth Costello instead moved to the first session, delivering a strident address against the human abuse of animals drawn word for word from the JM Coetzee novel that bears her name. Tired from travel like her fictitious namesake, Costello referenced the Jewish Holocaust to evoke the horrors of what is done to animals in laboratories—and, by implication, perhaps in art too.

Whatever the purpose or extent of the hoax (how many took Ms Costello for the real thing?), these ideas, while in many ways ‘old school,’ created an undercurrent that flowed beneath much of the day’s subsequent discussion. If Costello’s didactic tone was easily dismissed, the arguments themselves seemed to resonate at some of the symposium’s most ethically uncomfortable moments.

UWA’s Darren Jorgensen suggested that the ephemerality and even failure of bio-arts as a category doomed it, like all avant garde movements. Orlan’s idea of the living Harlequin Coat, he said, finished up as an installation; while Stelarc’s ‘third ear’ never hears. Jorgensen compared bio-arts to the 1970s ‘earthworks’ movement, which featured direct human intervention into the landscape. “Bio-art, like earthworks,” he said, “presumes to occupy and simulate the place of nature itself:” its subject is “ a new cosmological order.” Ultimately, the earthworks movement suggests an ethics of “being in a conscious relationship with a system,” rather than presuming that nature still exists as a discrete, non-human category.

SymbioticA’s Academic Coordinator and Co-Founder of the Tissue Culture and Art Project, Ionat Zurr, focused on the ethical discomfort of working in bio-arts. Growing a semi-living ‘stitchless jacket’ from immortal skin cell lines (Tissue Culture and Art Project, Victimless Leather, 2004) entails walking a somewhat visceral ethical borderline. Scientists and the military routinely “cross the line,” Zurr said, while few but the religious and artists ask questions. By creating “semi-living sculptures and/or objects of partial life,” Zurr aims to prompt thought about the meaning of such life. “As long as I’m uneasy about what I’m doing,” she said, “I’m in the right place.”

In “Interspecies Collaborations,” US artist Kathy High explored intimate relations between artists and animals through her own work and that of other artists. Focusing on recognisable and familiar animals, High introduced a literally ‘warm and fuzzy’ theme centred on relationship, and (citing theorist Donna Haraway) the importance of interdependence based on response and respect.

High’s presentation included discussion of two artists whose works lie at apparent extremes. In Adam Zaretsky’s Transgenic Pheasant Embryology Art lab, students manipulate pheasant embryos through a ‘window’ in the eggshell in order to create mutant living forms. Watching this tampering with a life form that US law doesn’t count as an ‘animal’ is subliminally disturbing, even if Zaretsky’s workshop aims to prompt ethical discussion. By contrast, former SymbioticA resident Kira O’Reilly collaborates with animals using a potent combination of critical engagement and empathy. The UK artist has both co-cultured the skin cells of newly-dead pigs with her own to create hybrid, living skin and devised confronting, tender durational performances including Falling asleep with a pig (which is just what it says) and inthewrongplaceness (2005) in which she cradled a slaughtered pig for several hours.

History sheds light on contemporary ethical practice: Ethan Blue, a US historian currently at UWA discussed the photographs of early 20th century prison doctor LL Stanley, who recorded his ostensibly ‘corrective’ experimental surgeries on prisoners with “different bodies.” For Blue, Stanley’s photos “amplify the terror and participate in the crime.” Blue believes Stanley was “just trying to see what would happen,” and the subtext is clear, if confounding: every scientist and artist sets their own boundaries (and often with ethics committees as compulsory arbiters), but how clear can the line ever be?

Bio-arts may face the same threat that not-for-profit researchers grapple with as life processes are increasingly commercialised, according to keynote speaker Luigi Palombi. An expert in biotechnology patents based at the Australian National University (ANU), Palombi provided a passionate and erudite explanation of the way entrepreneurs like Craig Venter are attempting to license gene sequences as though they are not discoveries but ‘inventions.’ Adding to earlier discussion around the commercial cloning and sale of human cell lines (often without patients’ consent), Palombi’s spectre of magnates like Venter profiting from ‘ownership’ of human products offered bio-artists rich territories for critical interrogation.

As the day drew to a close, two of SymbioticA’s current interdisciplinary researchers, Tarsh Bates (NZ) and David Khang (Canada), each asked, “How do we construct bodies when making art—who’s exploited, and how do we make political, ethical, poetic art?” Bates focused her attention on “what kind of world we desire,” explored through the lens of reproductive technology and complicated by race, geography, education and wealth. Khang, an artist and dentist, has produced visceral works juxtaposing extracted human teeth—markers of human mortality—with the poetic extremes of ox-tongues and butterflies. His gallery-based performances, such as How to Feed a Piano, employ symbolic language to confound cultural categories, including race.

In closing the symposium, SymbioticA Director Oron Catts pointed to the variety of critiques of biotechnology and bio-arts presented. Not only do the practices of art and science need to be ‘unpacked,’ he said, so too does the history of art itself and “the ethics of the hype” around scientific discovery and so-called ‘revolutionising’ research such as the Human Genome Project.

Catts stressed the acute need for bio-artists to provoke ethical consideration, from artists’ own informed and participatory perspective. Bio-art, he said, is sometimes judged by its ambiguity to be “flaky,” but this ambiguity is its strength: art sits in a privileged place where disturbances and disruptions provide powerful engagements with ethical issues but where problems need not be solved.

Body/Art/Bioethics symposium; SymbioticA —Centre of Excellence in Biological Arts, University of Western Australia, Aug 6

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. 27