voicing fear

tony reck: tamara saulwick, pindrop

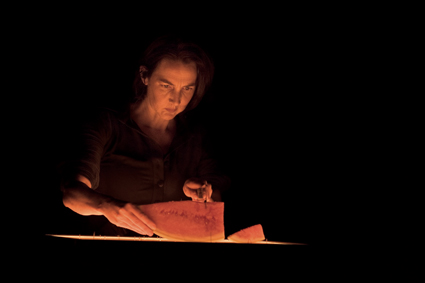

Tamara Saulwick, Pin Drop

photo Ponch Hawkes

Tamara Saulwick, Pin Drop

THE NORTH MELBOURNE TOWN HALL IS A STATELY EXAMPLE OF CLASSICAL VICTORIAN ERA ARCHITECTURE. IT MAKES SENSE THEN THAT PERFORMER TAMARA SAULWICK SHOULD COMMAND ATTENTION CENTRESTAGE WHILE INTERACTING WITH THE RECORDED VOICE OF AN ELDERLY WOMAN—ONE WHO MAY HAVE ONCE HUNG HER SHAWL ACROSS A BALUSTRADE WHILE DANCING WITH HER BEAU IN THE BUILDING’S GRAND HALL. BUT MORE LIKE THE OLD MOB-CONNECTED VICTORIA MARKET, STILL CONSORTING JUST AROUND THE CORNER, SAULWICK, INSTEAD, HAS FEAR ON HER MIND.

While listening to the elderly woman’s croaky recollections, Saulwick simultaneously relates a tale directly to the audience. Both stories are characterised by a general sense of disquiet. But it remains difficult to ascertain exactly the detail of each, as a circumlocutory speaker system situated above, behind and to the left and right of the audience, dislocates the content of both narratives. When the two tales collide, however, Saulwick’s live delivery splinters the elderly woman’s sonic representation, and the latter’s recorded voice undergoes a sonorous transformation. Tremolo, reverb and other software manipulations reduce the elderly woman’s voice to a singular chant or a sound resembling a repeated monotone emanating from a large gathering.

Meanwhile, Saulwick rises from her chair and advances upstage, situating herself behind a teak display case resting on a stand. As the recorded chant becomes incremental and fills the theatre, the artist tilts her display case up and forward, gradually revealing its contents: a pair of chrome plated scissors, a large plastic syringe, a roll of cellophane tape and a collection of automotive ties secured in a bundle among other objects. Simultaneously, the infiltration of sound that has vibrated throughout the inner ear coalesces into a recognisable phrase, “I did not scream.” The aural, visual, and verbal interplay comprising Pindrop integrates, relaying this and subsequent information precisely to the audience. We have witnessed a descent from the relative security of the actual world into the murk of the unconscious. But whether this descent has occurred within the mind of an unseen elderly woman or is, instead, a journey into the imagined experience of performer Tamara Saulwick, remains unclear.

Several distinctive female voices soon populate the theatre. One tells of the terror associated with receiving an obscene phone call. Another reflects upon its psychological implications—maintaining that fear is a natural human reaction, one that protects individuals in threatening situations. Fragmented and transient, these discharges of strategically placed sound are then subsumed by a coherent, recorded narrative. An apprehensive, upwardly mobile female voice speaks of hearing a suspicious noise in a bedroom of her Darlinghurst apartment. Investigating its source, she opens a wardrobe and out springs an assailant who thrusts her onto a bed where she endures a terrifying moment without end, in which her sense of personal safety is ruptured. The resulting violation then becomes a transitional moment for the performance. Saulwick, wearing a nondescript blue dress and knee high boots, absorbs the prolapse of light and sound, then regurgitates the same recorded tale, but now, as a real time narrative that engages while it disorients.

Interpreted as a commentary upon the mediated exchange, and the ancient tradition of oral storytelling, Pindrop skirts that interminable question: who, or what, is an author? But in spite of Saulwick’s alluring stage presence, some evocative imagery, a sophisticated lighting and sound design, and a movement vocabulary that speculates on the relationship between animate beings and inanimate objects, this fundamental question remains unanswered. Consequently, when the narrative shifts in location yet again, it does not generate empathy. Quite simply, amidst the 12 voices that proliferate throughout, I remain in doubt as to who is actually speaking.

Saulwick’s skill at self-directing in a tech-heavy performance is commendable. But I suspect she neglects some of the basic tenets of dramatic form. Who owns and undertakes the journey in Pindrop, and how does a performer locate within herself the experience of extreme fear, then express it theatrically? A very stylish and ambitious performance, these questions answered will assist in Pindrop’s potential being realised.

Pindrop, creator-performer Tamara Saulwick, sound design Peter Knight, movement Michelle Heaven, lighting design & production Ben Cobham & Frog Peck, costume design Harriet Oxley, Arts House, Future Tense, North Melbourne Town Hall, Aug 25-29.

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. 43