live work, women’s work

caroline wake: liveworks, performance space

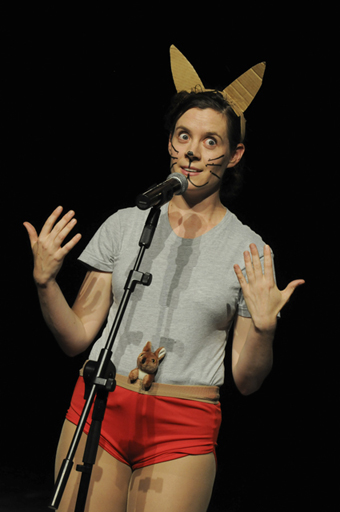

Talya Rubin, Of the Causes of Wonderful Things

photo Heidrun Löhr

Talya Rubin, Of the Causes of Wonderful Things

EARLIER THIS YEAR PLAYWRIGHT SUZIE MILLER NOTED IN THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD THAT OF THE 80 MAINSTAGE WORKS SCHEDULED FOR 2011, ONLY NINE (OR LESS THAN 12 PERCENT) WERE WRITTEN BY WOMEN. THE NEXT DAY THE PAPER PUBLISHED A PREDICTABLY INFLAMMATORY LETTER TO THE EDITOR FROM A MAN WHO WROTE THAT WHILE HE “REJOICE[D] IN FINE PLAYS BY WOMEN” NONE COULD BE CONSIDERED GREAT AND THUS THEY DID NOT DESERVE PROGRAMMING.

It’s a familiar argument and though Miller and the letter writer appear to be on opposite sides, they have more in common than they might care to admit, for they both define writing so narrowly it’s as if post-structuralism never happened. Surely, if we’ve learned nothing else, writing is about more than the words on the page; in the context of performance, we write with bodies, light and space as well as words. Taking this broader definition, it is clear that there are in fact many women “writing” for performance. Indeed, contemporary performance in this country is unthinkable without them—imagine the Sydney stage without Frumpus, the Fondue Set, My Darling Patricia, Post and Brown Council, to name just a few. Yet these names never feature in these annually rehearsed, rehashed arguments.

My frustration with the conversation was exacerbated by the fact that I had recently been to Liveworks at Performance Space where I had seen a number of strong works by women, who in fact dominated the program. Not that there weren’t some men too—Jiva Parthipan, Jason Maling, Paul Gazzola and Jason Sweeney on screen—but it was the women who caught my eye, working in a variety of combinations (solos, duos and groups) and forms (lectures, dances and comedies).

One of the strongest shows in Liveworks is Talya Rubin’s Of the Causes of Wonderful Things, which might also be called The Curious Case of Esther Drury and Her Five Missing Nieces and Nephews. In an atmosphere of carefully curated chaos—the stage is littered with lamps, chairs, piles of dirt and projectors—Rubin cuts back and forth between several characters including Esther, the police officer investigating the disappearances, Esther’s sister Claire who is in a relationship with an abusive French puppet called Frankie and Esther’s neighbour Mr Hiroshimoto. Rubin plays expertly with perspective, creating tiny scenes in a glass box, larger scenes projected onto the wall and some truly surreal interludes, such as when a donkey mask named Samuel takes to the stage in a town talent contest. With a judicious edit, this already unsettling and affecting show could become something truly special.

Paper People shares a similar aesthetic: the room holds a small stereo, a pile of white feathers, a wooden chair, a couple of microphones, cushions and a doll. We follow the performer around the room as she leans against a wall, rubs a doll against her breast, lectures us on audience participation, throws a red cushion in the air, eats a bowl of chillies and finally stitches herself to a man in the audience with red wool. The entire room holds its breath as someone hands him a pair of scissors and he cuts them apart one thread at a time. Paper People evokes a strange sense of intimacy, indeed the strangeness of intimacy itself: what it is to look into someone’s eyes (the performer is constantly looking at the audience with a mixture of invitation, resignation and resentment), share a favourite song, desire someone’s full attention and yet fear it, lest you prove lacking. Not that she does, and we leave the space wanting more.

Nicola Gunn, At the Sans Hotel

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nicola Gunn, At the Sans Hotel

Slightly less successful though no less suggestive is Nicola Gunn’s At the Sans Hotel, which begins with her character “Sophie” confessing in a faux French accent that Nicola couldn’t make it tonight. To compensate, Sophie gives us an overview of Nicola’s planned performance, complete with chalkboard drawings and references to Kazuo Ishiguro, Cornelia Rau and Rau’s alter ego Anna Schmidt. This is about the only interpretive clue on offer as Sophie continues to tell rambling stories in English and German before dancing with projections of herself and finally to Beyonce’s “Single Ladies.” Read with Rau in mind, At the Sans Hotel might be seen as a sort of “schizoanalysis” of her tragic case; read more broadly, however, it could be seen as a riff on what happens when we forget ourselves (in every sense).

Jane McKernan, Opening and Closing Ceremony

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jane McKernan, Opening and Closing Ceremony

While Gunn focuses on forgetting, Jane McKernan is more concerned with remembering. Resplendent in red shorts and flesh coloured stockings, she spends most of Opening and Closing Ceremony outlining a potted history of gymnastics and its less glamorous cousin “physie,” touching on Beijing 2008, Brisbane 1988 and the nature of community along the way. During this time she has been adding a tail, two ears and some whiskers to her costume and once it is complete, it’s showtime. McKernan lunges and stretches her way down the stage while a voiceover shares her inner thoughts about being a dancer and mother as well as her own childhood memories. In the final moments, she performs a triumphant routine to Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up.” Opening and Closing Ceremony is a gentle and humorous meditation on what it is to be shaped by gender, culture and nation or, more specifically, physie and Brissie in the mid-1980s.

Similar themes emerge in Colombian artist Claudia Escobar’s manola, which consists of a series of striking but not always legible images. The show begins with a bag inspection, continues with Escobar wandering the stage with a brick on a rope and boiled eggs in her mouth, and finishes with her sipping through a straw from a condom full of milk. It also includes Ahilan Ratnamohan as a transvestite Miss Colombia and then as a guerrilla fighter who captures and tortures Escobar, who whimpers, “I can no longer fantasise about my death.” In the dying minutes of the performance, she whispers “this is a secret between you and me;” but for the most part the secret remained hers and, because of the untidy scenography and underdone dramaturgy, was not something I could fully share.

Fiona Winning and Victoria Hunt are also concerned with the legacies of colonialism. Their Dancing the Dead deals with Hunt’s Maori ancestor Hinemihi, also the name of a tribal meeting house which was built in 1881 and survived the 1886 volcanic eruption, only to be sold for £50 to Earl Onslow in 1892. Onslow had “her” dismantled and transported to his estate in England, where she still stands. The most interesting parts of the lecture come when Hunt herself stands and explains how she might create a dance about Hinemihi: showing us how she might represent her spirit trapped in the rafters or the energy of the volcanic earth. This “performed conversation” between Winning, Hunt and members of Hunt’s extended family is not only useful background information for Hunt’s future performance, but also a careful memorial in its own right: one that conveys Hinemihi’s absence as well as her ongoing and dancing presence.

On a lighter note, Karen Therese uses the performance lecture form to cause her audience acute discomfort by talking about nothing but comfort. The show starts with Therese sitting behind a desk, wearing a blonde wig and sharing some of her ideas on her subject. She has also consulted with friends and, more interestingly, a corporate management book that identifies the “comfort zone,” the “danger zone” and, in between, the “optimal performance zone.” Therese spends the rest of the lecture detailing how she’ll achieve the optimal zone in this particular performance. (Brian Fuata sits stage left with words of reassurance and a cup of tea.) The show finishes when she pulls several people from the audience on to the stage and asks them to dance to Beyonce’s “Halo”—dancing in public, in this case the very definition of discomfort.

Brown Council, A Comedy

photo Heidrun Löhr

Brown Council, A Comedy

Perhaps the highlight of Liveworks is Brown Council’s A Comedy. For four hours, the four performers (dressed in dunces’ caps) place themselves at the mercy of the audience, as spectators select which comedy trick or trope they’d like to see next from a list that includes stand-up, the dancing monkey, cream pies and magic tricks. This is all done to a soundtrack of ‘boom-tish’ effects and the musak of late night talk shows. In staging a four-hour comedy, Brown Council bring a much-needed levity to durational performance, which can tend towards the solemn, even po-faced. But duration has a habit of turning even the humorous into the tortuous and, as the night wears on, we reveal ourselves to be petty, silly, mean and violent. When the piece finishes with an almighty food fight, it feels like a finale to Liveworks, even though it’s only Friday night. Two days later, A Comedy remains my favourite for its intelligent conception, excellent execution and the collective exuberance it unleashed.

In its own way, attending Liveworks was itself a durational performance and like any endurance effort there were some discomforts. The timetable was difficult to decipher and the timetabling itself somewhat strange—the theatres were rather empty on Thursday and Friday afternoons, and it wasn’t until Friday evening that the event really started to hit its stride. Then on Saturday, it seemed that there were more takers than tickets, meaning that some people missed out. Perhaps if the event were moved to take in Friday, Saturday and Sunday, more people might get to see these works in progress (as many of them were). This, in turn, might encourage them to come back to Performance Space not only for more “progress reports” but also for more adventures in live art. And when these adventures are “written” (devised, designed, directed and performed) by women, they have the potential to shift the conversation not only about women’s writing but about the nature of writing itself.

Performance Space, Liveworks: Fast & Furious, CarriageWorks, Sydney, Nov 11-14, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 18