How does your live art grow?: Liveworks, Performance Space

Jason Maling, The Vorticist

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jason Maling, The Vorticist

I ALWAYS FEEL EXULTANT WHEN I WALK INTO CARRIAGEWORKS DURING THE DAY AND DISCOVER SOMETHING CREATIVE HAPPENING. SUNLIGHT SHAFTS THROUGH, LIFTING THE BEAMED ROOF; PEOPLE EDDY FROM ROOM TO ROOM, VIVIFIED BY WHAT THEY’VE SEEN. THIS IS THE PLACE AT ITS BEST: ACTIVATED BY ART THAT INQUIRES, REGENERATES AND INTERACTS. USED ONLY FOR FINITE PURPOSE AND MATERIAL GAIN, CARRIAGEWORKS FEELS DEAD.

There is probably no event on its calendar that has greater potential to animate the place than Performance Space’s Liveworks, so it was disappointing to arrive Thursday midday and find CarriageWorks virtually empty. The Vorticist nonetheless was booked out—a one-on-one performance with a strong reputation honed over years. Artist Jason Maling was ambivalent about the context, deeming it “perhaps too theatrical,” but submitted the work because he wanted to be rid of it. At Liveworks, his usual process of building an archive was reversed, to become its deletion.

Dressed in waistcoat and tailored trousers, Maling leads his audience of one through a maze of corridors and stairs to a small, secluded space. You sit on the floor with him either side of a low table covered in handcrafted arcane tools and relics on paper from previous visitors. A tête-à-tête ensues with the artist. Intimacy is intrinsic to any one-on-one and the form can take this for granted and be conceptually lazy; so too artworks that request a story or secret from the audience. Yet The Vorticist, which started with this premise, ended with much more. What is this thing? Who were all these people before me? A trace installation of scrolls from years of such encounters, accumulated in a space above the foyer.

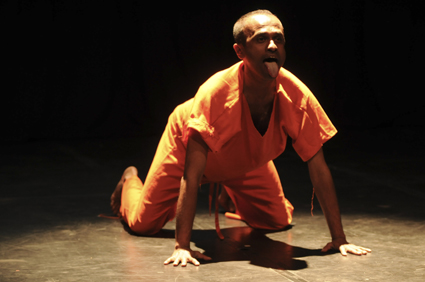

Jiva Parthipan, Last Remaining Relative

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jiva Parthipan, Last Remaining Relative

Jiva Parthipan’s performative lecture, Last Remaining Relative, recounted the artist’s recent emigration to Australia, interwoven with a series of anecdotes about international travel and art. Parthipan has been on the move his whole life: departure at age ten from war-torn Sri Lanka; decades in London; work around the world as an artist. Now he is in Australia under the visa category “Last Remaining Relative.” Constantly thwarted and harrassed by bureaucracy due to his race, Parthipan could have treated the subject harshly, encouraged into didacticism by the lecture format. Instead he was an engaging, witty, informative speaker, his true stories attaining an Orwellian absurdity. Pungent asides about the local bureaucracy finished the work perfectly. Some of the most eloquent moments were articulated with Parthipan’s body alone when he left the lectern to impersonate a tiger, then later a monkey. His performance set the political bar high at the festival, and no-one else topped it.

Linda Luke, Hoodie – Thirteen

photo Heidrun Löhr

Linda Luke, Hoodie – Thirteen

Thirteen by Linda Luke and Vic McEwan began in the foyer in the afternoon. A performance installation about homelessness drawn from Luke’s personal experience, titled Hoodie, was Part One. To McEwan’s gentle, eerie soundtrack, Luke slowly moved across the floor, half hidden and constrained by a hood. The wheeled contraption she employed part way through became an improvised skateboard, the perfect second prop. Luke was utterly in character, but the lack of audience drained energy from the work. Again through no fault of the artists, the work’s tent installation felt a little contrived as CarriageWorks management disallowed the artists from inhabiting it full-time for the three days the performance ran. I regret not making it to Part Two.

Thrashing Without Looking

photo Heidrun Löhr

Thrashing Without Looking

Thrashing Without Looking by Martyn Coutts, Tristan Meecham, Lara Thoms, and Willoh S Weiland was an interesting combination of light-hearted enjoyment and psychological challenge for those who fear the unknown or loss of control. It provoked all sorts of thoughts about the modes of disembodied communication we engage in now—televisual, internet—how trust and agency are still called upon and how intense and liberating is the sense of touch. There were moments of alienation, boredom, confusion, anticipation, humour and the ending was surprisingly tender. I didn’t want to leave.

I Luv Amanda Crowe, a work about teenagers in 80s suburbia—a strangely dominant trope in Australian performance—floundered through lack of content, courage and form. Surely adolescent desire connotes fear, tenderness, pathos, embarrassment, but all the embarrassment expressed by the performers seemed to be more about the work than its actual subject matter. Even the superlative Georgie Read couldn’t save it. The performance begs a question that came to mind frequently throughout the festival around the programming of works-in-progress.

By contrast, Brown Council’s A Comedy came to Liveworks honed by years of the quartet’s explorations of modes of comedic entertainment in performance. The masterstroke lies in their recent meld of traditional comedy with endurance via a slightly sporty aesthetic. They pushed this even further at the last minute by deciding to create a single four-hour performance instead of one hour slogs back to back. Everything is distilled: the girls’ plain black outfits; their coloured dunce caps, cannily distributed among the audience as well; the bare stage; the casual demeanour of the three performers up the back chatting and eating peanuts while their fourth is in the hot seat. The peanut gallery, of course.

Brown Council, A Comedy

photo Heidrun Löhr

Brown Council, A Comedy

A Comedy was built on five tricks, vaudeville classics such as cream pie throwing as well as stand-up. Others like the dancing monkey go back millennia and, merely by being humanly conveyed, revealed their sinister side—banana gorging, face slapping: our gluttony and lust for violence and desperation to please. There was a tremendous command of material from every one of the performers—Fran Barrett, Kate Blackmore, Kelly Doley and Diane Smith—the discomfort and hilarity building by the hour. Utterly compelling, with much food for thought.

Into/Out of Me by Brigid Jackson posed the question: To what extent does my body belong to me? Occupying a small dressing room for just under two hours, with Benjamin Cittadini manipulating sound, Jackson began on the floor, blowing up and tying off plastic bags. She gradually moved to stalking in a tight circle, making the occasional incision on her chest, dripping milk into the blood with an eye-dropper. Taped to the mirrors around the room were little sachets of hair, nail clippings, blood. In the program the work was described as an exploration of the boundaries of bodies and what is left behind, the latter less personal than the former. Yet the body remnants around the room remained disconnected, the performance itself not coherent. Like the hospital gown they didn’t articulate beyond signalling that Into/Out of Me was about the body. Nevertheless the audience seemed hungry for this sort of intimate, visceral performance, in a festival otherwise sadly devoid of it.

David Cross’s Hold, from Performance Space’s Nighshifters program, was a perfect companion piece to the Liveworks. Entering the installation I was awestruck by the size of the inflatable, a weird hybrid of ship and castle. Climbing into it was daunting and exciting, the appearance of what seemed a fake hand something to be avoided. Then, on the crest, a choice has to be made: fears surmounted, the audience’s agency absolutely intrinsic. The sheer audacity and sculptural beauty of the work opened further, enhanced by the dilemma of how to negotiate trust with a stranger and the question of reciprocation. A beautiful twist occurs in the middle, the whole experience profoundly moving. Cross performed a companion piece on Saturday morning in the blazing sun opposite the farmers’ market. In a sense Hold’s microcosm, it again tackled reciprocity and engagement this time with a small contraption worn on the artist’s head, activated—or not—by a partner. One hand, one eye; the necessity of action. Confronting from the inside, entertaining from the outside. The simplicity of these elements and the artist’s immense effort produced a complex work that, like Hold, made an endless variety of connections.

Cross’s work benefited greatly from its accessible positioning and in the range of people it reached. With so much of Liveworks dependent on audience interaction —Thrashing, Thirteen, A Comedy, to name a few—it seemed a shame to let performances languish in the barely attended daytime working week slots. Saturday afternoon by contrast had so many events on simultaneously you were bound to miss many. Even then, many people I know who attend cultural events every weekend didn’t know about Liveworks. Full price tickets for works-in-progress, some barely begun, created more hindrance to healthy numbers.

There is the danger of insularity. Indeed, the lushest party was the restricted artists’ event at kick-off; by contrast, after Night Time on Sunday night, full and buzzing, the foyer sadly emptied. Can the performance world accept its marginal status to the point of complacency? And how much longer can CarriageWorks be so unaccommodating and expect to survive culturally? Moved to straddle a whole weekend and offered to a broader audience, Liveworks could blossom. CarriageWorks itself, in spite of its resistance to date, could still be the best place for it. What seems ancillary—fairly priced good coffee; bars and restaurants worthy of the neighbourhood, open late as befits a mature culture; a decipherable and well distributed program—could be linchpins. The possibilities are endless.

–

Performance Space, Liveworks: Fast & Furious, CarriageWorks, Sydney, Nov 11-14, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 20