pixels ain’t square, man! seeing the digital light

darren tofts: public symposium, digital light: technique, technology, creation

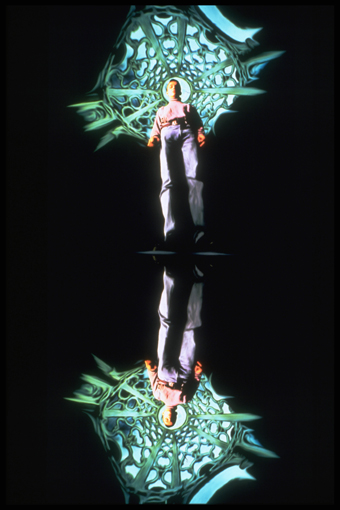

Rekindling Venus: In Plain Sight 2011, Lynette Wallworth, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival

photo Tony Lewis

Rekindling Venus: In Plain Sight 2011, Lynette Wallworth, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival

SOME TIME DURING THE WINTER OF 2010 I FOUND MYSELF BASKING IN THE WARM, SYNAESTHETIC GLOW OF AN ANACHRONISTIC SUN. THE DECKCHAIR ON WHICH I RECLINED PROVIDED JUST THE RIGHT VANTAGE POINT FOR CONTEMPLATION OF THE WONDERS OF ARTIFICIAL SUNSHINE. RATHER LIKE THE SUN DOMES OF RAY BRADBURY’S SHORT STORY “THE LONG RAIN” (1950), RAFAEL LOZANO-HEMMER’S GLORIOUS SIMULATED SUN INSTALLED AT MELBOURNE’S FEDERATION SQUARE OFFERED WELCOME RESPITE FROM INCLEMENT WEATHER. AS PART OF THE CITY OF MELBOURNE’S LIGHT IN WINTER FESTIVAL, SOLAR EQUATION RESONATES AS A PARABLE OF THE UBIQUITY OF DIGITAL LIGHT, ITS AMBIENCE IN THE CONTEMPORARY BUILT ENVIRONMENT, ITS FACILITY IN ENABLING SO MUCH OF WHAT WE SEE AND ITS REMARKABLE CAPACITY TO SUBSTITUTE APPEALING COPIES FOR THE REAL THING.

Such themes were among the concerns of the two-day Digital Light symposium, the public face of Genealogies of Digital Light, an ARC (Australian Research Council) Discovery project that seeks to provide a critical account of digital light-based technologies “by tracing their genealogies and comparing them with their predecessor media.” The principal researchers of the project and organisers of the conference—Sean Cubitt, Daniel Palmer and Les Walkling—conceived the event around a number of questions, chief among them the issue of how Australian and international artists working with light-based technologies are considering “the capacities and limitations of contemporary digital processes” in their work.

This reflexive gesture was welcome, for at face value the notion of digital light, in itself, is not immediately compelling as a framing theme for a packed two-day program of speakers. As if adding to my growing relief, Sean Cubitt’s opening remarks set the right conceptual tone for the event, asserting that there is still a “general ignorance” regarding digital technologies and how they actually work, despite their omnipresence in our lives. While this polemical sortie clearly identifies the research opportunity of the project, it also opened up a dialogue to do with the realpolitik of the digital, providing a reason why members of the public would bother giving up half their weekend to attend such a conference. Alvy Ray Smith, computer graphics pioneer and co-founder of Pixar, detailed the extraordinary and exponential development of computational power since the early 1960s in an entertaining and authoritative talk. He also set the digital record straight on a crucial point: pixels are actually round, not square.

The pixilated, block aesthetic of the 1980s and 90s that signified the emergence of the digital world was in fact an optical illusion, a mis-seeing of digital light. In a similar spirit of critical revisioning, Geoffrey Batchen boldly asserted, “photography has always been embedded in the DNA of digital media.” Among the many exquisite examples he discussed to support his position was Henry Fox Talbot’s 1839 contact print of two pieces of lace that he presented to Charles Babbage. “It’s as if Talbot wants to show us,” Batchen suggests, “that the photograph too is made up of a series of smaller units”—in other words, round pixels. Appropriately closing the show, Victor Burgin’s conceptually rich presentation also détourned the histories of cinema and photography, returning to their very origins in the manipulation of light and its capacity to fool the eye. Burgin’s own recent practice of compositing moving, panoramic montages from sequences of still images, evidenced the uncanny and even unsettling sensation of moving through a natural landscape that does not move with you.

The event certainly brought together an impressive who’s who of Australian and international artists, curators and technological innovators worthy of the radiance of Lozano-Hemmer’s sun. In this the symposium provided the refreshing opportunity to engage with historical perspectives alongside glimpses of contemporary aesthetic practices that explore the notion of digital light. Lynette Wallworth’s beautiful Rekindling Venus series engages with her concerns about the impact of climate change on ecosystems, using a cell phone app to transform hand-held media into a “virtual porthole to coral reefs and connected real-time data.” This canny use of augmented reality brings to life the illusion of a vibrant, three-dimensional world of fragile beauty. The symposium also offered Jeffrey Shaw the opportunity to document his long association with the wonders of light, from his expanded cinema events of the 60s, his light shows for bands such as Genesis in the 70s, to his immensely rich and varied experiments with immersive and interactive cinema and the convergence of real and virtual spaces as manifestations of light: a history that in itself charts the sedimentary record of artists working with digital technologies during the last decades of the 20th century, as well as looking back to the trompe l’oeil experiments of Baroque optics and illusionism in painting and architecture. Similarly, Stephen Jones’ comprehensive history of early electronic art within Australia added to the sense of a rich heritage of experimentation with digital light in this country. And as luck would have it (or was it an artefact of the digital?) Jones’ long awaited book Synthetics: Aspects of Art and Technology in Australia, 1956-1975 (MIT Press, 2011) was hot off the press, providing a concrete instance of the longevity on show in both his and Shaw’s presentations.

Heaven’s Gate 1987, Felix Meritis 1787-1987, Shaffy Theater, Amsterdam, Netherlands

With the advent of the minutely small (such as nanotechnology and biomechanics), a deeper questioning of the metaphysics of digital light is emerging, whereby the notion of “seeing,” as curator Christiane Paul eloquently described, becomes irrelevant. This alternative epistemology of light was taken in a different, haptic direction by Stephen Jones back to the telegraph in his re-tracing of the digital as a strict micro-economy of “on/off,” associating the digital “picture element” with the dots and dashes of the telegram. Alvy Ray Smith decisively quashed the hype around 3D TV and cinema, pointing to the misconception that 3D was ever possible on the two-dimensional screen to begin with, since it “happens in the brain, not in the display.” Smith also contributed to this galvanizing counter-phenomenology of digital light at the symposium with one of the most memorable aphorisms of the event, “Reality begins at 80 million polygons per frame.” But reminding us of Lucasfilm’s famous acronym REYES (“renders everything you ever saw”) may prove to be the boldest gauntlet thrown down to artisans of digital light in their quest for the highest-fidelity vision; the ultimate dream when the map will surely replace the territory.

Digital Light: Technique, Technology, Creation Public Symposium, University of Melbourne, March18-19, 2011

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 20