tribute, legacy & radical revisionism

keith gallasch: wendy martin, curator, spring dance 2011

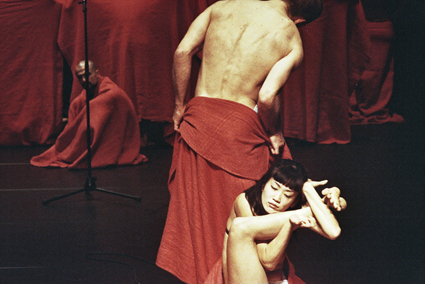

For Pina, les ballets C de la B

photo Chris Van der Burght

For Pina, les ballets C de la B

FORMER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE HEAD OF THEATRE AND DANCE, AND SPRING DANCE CURATOR, WENDY MARTIN IS NOW HEAD OF PERFORMANCE AND DANCE AT LONDON’S SOUTHBANK CENTRE WHERE SHE SAYS SHE’S ADJUSTING AFTER SEVERAL MONTHS TO A NEW WAY OF LIFE, INCLUDING ENCOUNTERING MORE DANCE THAN SHE’S EVER SEEN. SHE’S PARTICULARLY PROUD OF THIS HER THIRD SPRING DANCE FOR THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE, A PROGRAM OF DISTINCTIVE INTERNATIONAL WORKS AND, FROM AUSTRALIA, ROS WARBY’S MONUMENTAL AND CHUNKY MOVE’S I LIKE THIS.

dv8: can we talk about this?

Martin describes Lloyd Newson’s new work, Can we talk about this?—with its international premiere in Spring Dance—as fusing dance and verbatim theatre to deal with the issues that arise from the 1989 fatwah placed on Salman Rushdie, the threats to the life of a Danish cartoonist for his representation of Muhammad, and the murder of Theo Van Gogh for his criticisms of Islamic culture. It seems that the work will focus particularly on the oppression of women and children in a work rich in interview-based dialogue and inventive choreography. Martin reveals that the cost of presenting Can we talk about this? “was almost beyond us, but the Opera House made the commitment.” She was intrigued that the work was co-produced (with European partners) by The National Theatre of Great Britain “rather than with London’s Sadlers Wells.” This is further evidence that there are works and audiences that crossover and hybridise, as in the programming in Australia of works by Lucy Guerin in Malthouse and Belvoir subscription seasons. Given its subject matter and, apparently, the manner in which it’s played direct to its audience, Can we talk about this? is bound to be as provocative as it is inventive.

les ballets c de la b: out of context, for pina

Coming close on the heels of the sell-out screening of Wim Wenders’ 3D film tribute to the late Pina Bausch at the Sydney Opera House, comes Alain Platel’s tribute. Like DV8’s Lloyd Newson, says Martin, Platel believes that without Bausch his own work would not exist. Platel was taken by the way that Bausch’s creations would “step out of the everyday” and give so much creative responsibility to her dancers (among whom have been a number of Australians). Platel’s tribute pays homage to Bausch’s unique approach but, says Martin, uses the popular music and dance moves of our own time, as well as Bach, to make the connection with his own work for les ballets C de la B. Jana Perkovic wrote, on seeing For Pina at Sadler’s Wells in 2010: “The piece defies description by virtue of sheer over-accumulation: 90 minutes of startlingly original movement with virtually no repetition, on nine different physiques that, even when amassed into synchronicity, preserve individual differences…Not having any narrative frame allows the audience to experience this decontextualised mass of movement on the level of affect, not cognition, free-associating stage images to deep memories. The result is emotionally penetrating and deliriously enjoyable.” (RT98)

pina: a celebration

Further acknowledgment of the Bausch legacy comes on screen over two days in the form of Anne Linsel’s Pina Bausch, a film, and Linsel and Rainer Hoffman’s documentary about the creation of one of the greatest of the choreographer’s works, Kontakthof. (The program will also include Life in Movement, the documentary about the late Tanja Liedtke.) Speakers in the accompanying discussions about Bausch will include Meryl Tankard, Michael Whaites, Kate Champion, Shaun Parker and Lutz Forester who all performed with Bausch’s company.

Israel Galván

photo Felix Vazquez

Israel Galván

israel galván: la edad de oro

When at the Lyon Biennale de Danse in 2007, I saw a gypsy flamenco ensemble perform, unadorned by frills and garish lighting, it was one of those revelatory experiences that put you in touch again with a form that had come to mean little. Martin has seen three works over the years by Israel Galván, a “flamenco revisionist” who brings together traditional form with contemporary dance. In Rome she witnessed him “dance barefoot, kicking up whirls of white dust while accompanied by a pianist.” She was also intrigued by the way “he blurred the masculine and feminine in his form” and accentuated the shape of his dance by largely performing in profile so that every movement detail could be relished. RealTime contributor Erin Brannigan told me she thought Galván’s performance in this year’s Montepellier Danse the best in the program.

Ros Warby, Monumental

photo Jeff Busby

Ros Warby, Monumental

ros warby: monumental

Although previously enjoyed by Sydney dance audiences courtesy of Performance Space at CarriageWorks in 2009, Martin hopes that Warby’s Spring Dance presentation of Monumental will bring her the much larger audience this truly idiosyncratic Australian dancer deserves. There’s much about Warby to be found in RealTimeDance, including my review of Monumental (RT90). I wrote (and it’s not an easy work to put into words, believe me): “The anti-gravitational appeal of dance is, of course, like our dream of flight and winged selves, but here the embodied connection goes deeper. The audience become birdwatchers who, by way of Warby-Medlin [film]-Mountford [cello] alchemy, suddenly sense not only the dancer’s ‘birdness,’ but also their own, and, as they cast their minds back to Monumental’s opening image, the birdness (and not just of swans) of ballet.” Monumental is visually magical, sometimes funny and has some very interesting things to say about dance…and nature.”

Blazeblue Oneline

photo Byron Perry

Blazeblue Oneline

chunky move: antony hamilton & byron perry’s i like this

Dancers Antony Hamilton and Byron Perry have contributed significantly to the works of Melbourne choreographers, so it’s wonderful to see them step out as a duo with their own creation about the magic of ‘thingness’ as they manipulate themselves and objects about the stage. RealTime reviewer Carl Nilsson-Polias had been impressed with Hamilton’s Blazeblue Online (RT85); he noted “a subtle recurrence of two-dimensional objects, such as cardboard, being given three-dimensional life and movement by the dancers. It is as though the flatness of visual art’s canvas is itself being reconstructed and reconfigured into the dynamic physical nature of dance.” John Bailey wrote of I Like This: “[Perry and Hamilton’s] visual design for the work deserves particular mention, becoming a character almost in itself, with hundreds of perfectly executed changes whose sometimes stroboscopic effect makes lighting operation appear a form of choreography in its own right. It’s self-reflexive dance, certainly, but by incorporating technology in such a sophisticated way it becomes something much more…the result approaches the sublime” (RT89). You can read Sophie Travers’ interview with Antony Hamilton in RT93. For Wendy Martin, I Like This is indicative of the work of a new generation of Australian choreographers, in this case designing, making and controlling an environment before us.

fevered sleep: the forest

UK group Fevered Sleep’s The Forest became part of the Spring Dance program, says Martin, on the recommendation of Brisbane Festival artistic director Noel Jordan. Aimed at young people and families in particular, but not at all exclusively, this maze-like, glass and mirror installation brings together dance, sound and light to create what Martin describes as “interactive dance theatre.”

placing spring dance

The contrast between Melbourne’s Dance Massive and Sydney’s Spring Dance is palpable given the largely national content of the former and the international purview of the latter. Martin is impressed by Dance Massive and sees the two dance events as equally important. Part of her inspiration for Spring Dance came from witnessing large-scale dance events in Germany in 2007-08 “with so much audience and performance engagement, so much conversation—a story going beyond one show—and asking huge audiences to take risks.” A single show at the Opera House might draw 1,500-2,500 ticket sales, she says—unless it’s Akram Kahn pulling 6,000 or so sales. But the 2010 Spring Dance attracted 20,000 people including 13,500 ticket buyers. Martin believes that Spring Dance is a sustainable model for audience development. It’s certainly what Australian dance needs. Of course, should Spring Dance continue now that Wendy Martin has left the Opera House, the event could be what Sydney dance artists also consistently need, greater exposure to local audiences in an international context as enjoyed by the Spring Dance production of Meryl Tankard’s The Oracle in 2009 and Narelle Benjamin’s In Glass in 2010.

–

Spring Dance, curator Wendy Martin, Sydney Opera House, Aug 23-Sept 4

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 4