outsiders & others

katerina sakkas: 2011 sydney underground film festival

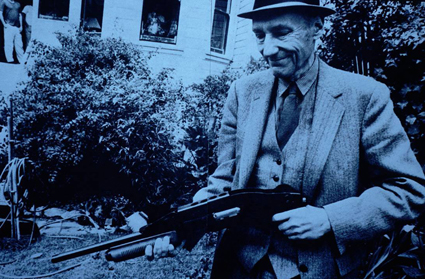

William S. Burroughs—A Man Within

THIS YEAR’S SYDNEY UNDERGROUND FILM FESTIVAL OFFERED AN EXCELLENT LINE-UP OF PROVOCATIVE FILMS SPANNING DOCUMENTARY, SEXPLOITATION, SPOOF, HORROR, ANIMATION AND THE EXPERIMENTAL, WITH PLENTY OF CROSSOVER BETWEEN GENRES.

An outsider theme permeated many of the features on show. From Yony Leyser’s documentary portrait of William S. Burroughs, experimental filmmakers in Free Radicals, through to the transformative relationship of The Ballad Of Genesis and Lady Jaye and the studies of prostitution in Guilty of Romance, X and Profane, there was a sense of filmmakers wanting to explore unorthodox lives.

william s burroughs: a man within

The perennially cool William S. Burroughs loomed large over the festival. In creating his portrait of the conflicted, crazily influential iconoclast, Yony Leyser presents a multitude of interviews with those touched by Burroughs: fellow Beatniks, ex-boyfriends, biographers, artists, filmmakers, including John Waters and Gus Van Sant, and punk rockers Patti Smith, Iggy Pop and members of Sonic Youth and The Ramones. Recently released archival footage shows Burroughs reminiscing with Allen Ginsberg about the Beat movement. A beautifully textured soundtrack contributed by various punk luminaries and Morocco’s Musicians of Jajouka is often overlaid with Burroughs intoning typically searing lines.

Though there are a few anecdotes about his youth, the documentary devotes itself largely to the years following Burroughs’ emergence as a writer, dating roughly from the awful incident in 1951 when he killed his wife, Joan Vollmer. Given Burroughs’ incredible cultural reach (Laurie Anderson notes, “William seemed to have a connection with anything and everything”), a picture emerges not only of the man, but of the second half of the 20th century, an era defined by a series of radical changes—manifest in the Beat Generation, queer activism, Punk—steered in some way by Burroughs.

The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye

the ballad of genesis and lady jaye

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge—performance artist, Punk musician—was mentored by Burroughs and appears in Leyser’s documentary. Another of his mentors, Burroughs collaborator Brion Gysin, invented the ‘cut-up’ method (adopted by Burroughs) where pages of type were scissored and aligned to form unexpected new meanings. This method influences the unconventional relationship at the heart of Marie Losier’s intimate documentary, The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye. “When you’re madly in love with someone,” P-Orridge proffers, “you want to consume each other…not be individuals any more.” He and his wife, performance artist Lady Jaye, embarked on a project to become as physically alike as possible through various measures, including cosmetic surgery, cutting and recombining themselves à la Gysin in order to create a “third entity”—the Pandrogyne.

P-Orridge dominates the documentary. It’s packed with his whimsical utterings; performances old and new; footage of his seminal industrial band Throbbing Gristle and the more recent Psychic TV; and personal anecdotes, including one of being violently bullied as a schoolboy. Lady Jaye in contrast remains something of an enigma. The pastel-infused cosiness characterising the film is tempered by a revelation towards the end, making it as much requiem as frothy documentation of an off-beat love.

free radicals

Pip Chodorov, thanks to his director father Stephan, was steeped in experimental film from childhood. He presents an engaging, often humorous celebration of the subject in Free Radicals. The title, taken from a 1958 four-minute animation by New Zealand born artist Len Lye, perfectly encapsulates the defining philosophy of experimental film as Chodorov sees it—absolute freedom from rules in a radical reaction against conventional realist cinema. Lye’s animation is one of many experimental works played throughout the documentary, which charts the movement’s growth from early post-WWI Dadaist stages to a blossoming in 60s and 70s counter-cultural America. Chodorov conducts laid-back interviews with leading practitioners including Peter Kubelka, Jonas Mekas, Maurice Lemaître, Nam June Paik and Ken Jacobs. There’s also footage of pioneers, the late Hans Richter and Stan Brakhage (who coined the term ‘underground cinema’). Chodorov’s infectious enthusiasm should swell the ranks of budding experimental filmmakers everywhere.

tomie unlimited

No underground film festival is complete without something twisted from the horror genre, and SUFF didn’t disappoint in this regard, showing former Troma director Trent Haaga’s Chop alongside Japanese shockers Helldriver and Tomie Unlimited. The latest of several films based on Junji Ito’s Tomie manga series, Tomie Unlimited (Noboru Iguchi, 2011), centres on Tomie (Miu Nakamura), a vengeful schoolgirl who, as the title suggests, cannot be destroyed, but keeps cropping up in an assortment of ever more bizarre and repulsive manifestations, with the primary aim of tormenting her younger sister Tsukiko (Moe Arai). Tomie often relies on displacement, a standard horror technique which has things appearing where they don’t belong: identical miniature heads in a school lunchbox, for example, or a dead schoolgirl returning to the bosom of her family.

While Tomie Unlimited might begin in a (relatively) restrained manner, it certainly doesn’t finish that way. As with the magnificently off-the-wall Helldriver, whose director Yoshihiro Nishimura created Tomie’s special effects, this fim’s horror is ultimately about excess; though bizarre, it’s not aiming at profundity. Both films are fabulously inventive when it comes to the sheer variety of mutations they present, something that’s led to comparisons with David Cronenberg’s body horror. To some extent the comparison holds, but Tomie replaces the Canadian director’s broader social anxiety with the intimate jealousies and injustices lurking within a schoolgirl’s network of relationships.

Guilty of Romance

guilty of romance

If a Burroughs thread ran through the festival, so did one of prostitution, evidenced in films like Usama Alshaibi’s Profane (which promised an intriguing discourse on the collision between Islam and sex work, but failed to deliver), Australian thriller X and Sion Sono’s Guilty of Romance (2011), which opens with a gruesome murder in a Tokyo ‘Love Hotel’ district. Travelling back in time, Guilty Of Romance follows Izumi (Megumi Kagurazaka), a young woman missing since the murder. Through a series of chance events, Izumi, who is caught in a subservient, sexless marriage, finds herself turning from glamour modelling to casual sex then prostitution. She discovers a mentor of sorts in Mitsuko Ozawa (Makoto Togashi), a literature professor/streetwalker who drops references to Kafka’s The Castle and seems to view prostitution as the ultimate act of bodily actualisation.

Dark and richly detailed, in some ways recalling Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967), Guilty of Romance presents a woman in search of her own sexual degradation. There’s an interesting existential element to the film’s ruminations on female sexuality, somewhat undermined by the titillating depiction of some fairly demeaning encounters (and a certain double standard when it comes to male versus female nudity). It’s complex enough however to make for a problematic but absorbing meditation on the failure of romantic ideals (as symbolised for the protagonists by Kafka’s unattainable castle).

x

The Australian film X, like Guilty of Romance, is a thriller focused on female prostitutes: one seasoned; one neophyte, but there the comparison ends. X’s depiction of the sex trade is anything but titillating. As much character study and geographic portrait as thriller, writer-director John Hewitt and co-writer Belinda McClory’s film concentrates on a night when the lives of two prostitutes intersect in Sydney’s Kings Cross. After witnessing their drug-dealing client’s murder, Holly (Viva Bianca), a successful call girl on the brink of retirement, and Shay (Hanna Mangan-Lawrence), a teenage newcomer to the sex trade, suddenly find themselves on the run. Fear, a natural component of any thriller, drives the film at this point, insinuating itself into the landscape. “RUN,” reads graffiti on a wall. “NOW,” shrieks a hairdresser’s sign. As the characters tear along Darlinghurst laneways or traverse the lurid stretch of William Street, an impression of the Cross’s predatory nature builds—this is a place that won’t let people escape.

Hewitt broadcasts Sydney’s identity throughout the film, using the city’s bright lights and glittering skyline to highlight his protagonists’ gradually shattered aspirations. While the thriller format slightly reduces X’s realism, Bianca and Mangan-Lawrence give deeply convincing performances, and the end of the film echoes Midnight Cowboy (1969), another account where a character’s circumstances prevent the realisation of a dream escape.

2011 Sydney Underground Film Festival, Factory Theatre, Sydney Sept 8-11

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 23