manifesting the unexpressed

danni zuvela: brisbane international film festival 2011

Fantome Island

TWO YEARS AFTER ITS DRASTIC REMODELLING, THE 2011 BRISBANE INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL CAPITALISED ON WHAT HAS HISTORICALLY BEEN ONE OF ITS GREATEST STRENGTHS—LOCAL AUDIENCES’ THIRST FOR DOCUMENTARY CINEMA—WITH A WELL-PROMOTED EXTENSION OF THE NON-FICTION PROGRAM. REBRANDED AS BIFFDOCS, THE DOCUMENTARY SMORGASBORD INCLUDED LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL FARE INCLUDING UNFLINCHING EXPOSÉS, CONFRONTING CONFESSIONS AND AFFECTIONATE PORTRAITS, AND OFFERED A NEW COMPETITIVE PRIZE FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY AT THE FESTIVAL’S CONCLUSION.

fantome island

Queensland filmmaker Sean Gilligan’s first feature-length documentary, Fantome Island, interlaces thoughtful interview material with meticulous archival research to bring to light the extraordinary tale of Queensland’s forgotten leper colony. North-east off the coast of Townsville, the Fantome Island leprosarium and its Aboriginal inhabitants were shrouded in secrecy by the state health authorities. The film tracks the journey back to the island by a survivor, Joe Eggmolesse, whose articulate reflections—evidently extracted from hours of interview—are skillfully used to bind and humanise the story.

Gilligan’s achievement is to critically highlight an important new chapter in a now well-known story: the disproportionate suffering of Indigenous people, as much from introduced infectious diseases as from the historical erasure of the particularity of their experience. Fantome Island reverses that tendency with tenderness, insight, and most importantly, richly imaginative detail (a feature shared by another Indigenous-themed doco at the festival, Daniel James Marsden’s 2011, The Clouds Have Stories: The Art of the Torres Strait Islands). While there are incontrovertible links with stolen generation policies, it’s not hard to see in Fantome Island’s central narrative of forcible removal of the unfit by authorities to a remote island prison something of a metaphor for the founding of the nation itself. Fantome Island is the kind of profoundly humane documentary experience that resonates with a rigorous awareness of the social conditions from which it arises.

uma lulik

Uma Lulik

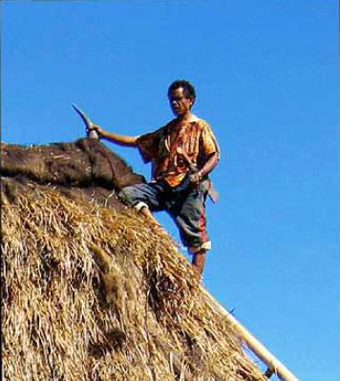

Another significant event at BIFF 2011 was the screening of Uma Lulik, the first documentary entirely made in East Timor by an East Timorese filmmaker, Victor De Sousa. It is hard to understate the significance of the Uma Lulik, or Sacred House, in Timor Leste consciousness. As the eternal resting place of family spirits, a place where the living gather to remember and honour their dead, the spirit house occupies a central position in the community. Every 10 years, the community rebuilds the spirit house’s physical structure, in the process maintaining, fortifying and renewing their spiritual connection both to forebears and the land in which all are embedded.

Over the course of Uma Lulik, we follow the remaking of a spirit house, beginning with palm-fringed jungle daybreak, through the fashioning of building materials to erection of the structure. As it documents this communal act of devotion, the film provides us with access to the Timorese sensibility to do with the dead—not as departed but as ever-present, woven through and very much dwelling within the community, resident in the divine structure of the spirit house. This story of the divine—as De Sousa’s poetic text at the opening puts it, “the story they have told me”—is communicated as much through the seemingly prosaic acts of chopping wood or binding eaves as it is through mourning rituals and collective ecstatic song.

the trouble with st mary’s

That mainstay of documentary production, the maverick figure, featured heavily in the BIFFDOCS program, with a number of stories about rebels and trouble-makers benefiting from the feature-length format’s enhanced opportunity for reflection. Local firebrand priest Peter Kennedy, the 72-year-old insubordinate sacked by the Catholic Church in 2009, was the subject of a searching examination by the formidable documentarian Peter Hegedus in The Trouble With St Mary’s. Observing Kennedy and his 1000-strong flock as they come to grips with their exile, Hegedus’ typically intelligent consideration delves into the man and the practices—alteration of ritual processes, allowing women to preach, blessing gay couples and uncompromising commitment to social justice causes—that so infuriated the church orthodoxy. This conscientiously balanced film offers a subtle diagnosis of the role of the progressive South Brisbane suburb of West End as the crucible of the trouble with St Mary’s church.

heroes, legends, rebels

Two films about powerful women stood out: Leila Doolan’s Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey, about legendary Irish political activist Bernadette Devlin, and A Bitter Taste of Freedom, about the assassination of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya. Acclaimed filmmaker Marina Goldovskaya pieced together the final years of her friend, showing her to be by turns fearful of and defiant towards the corrupt Russian authorities into whose activities she clearly probed too deeply.

A hellraiser of a different kind, country music showman Chad Morgan, was the subject of the film I’m Not Dead Yet. Janine Hosking’s portrait documents how the buck-toothed Morgan has attained legendary cult status as much for his bawdy banter between numbers as his dipsomaniacal exploits, both of which are well-documented throughout. The relaxed Sunday afternoon screening time for this film unfortunately clashed with another tribute to an Australian rebel, the retrospective of Sydney experimental film and surf movies guru Albie Thoms. The screening included Thoms’ the cheerfully libertine 1963 film experiment, It Droppeth as the Gentle Rain, a compact selection from the independent Ubu Films collective he co-founded in 1965, and a rare opportunity to view his 1979 post-counter-culture surf movie, Palm Beach. While ostensibly a narrative feature about Sydney surf miscreants, Palm Beach evinces its maker’s experimental theatre heritage with a complexly layered sound montage and compelling adlibbed performances from a cast of mostly non-professional actors, surfers and a pre-stardom Bryan Brown and Julie McGregor.

biffdocs winner: kim ki-duk’s arirang

The 2011 festival offered both ‘traditional’ festival films and fun alternatives (notably, the recreation of a drive-in cinema complete with sentimental family fare and shlocky B-movies). In what is one of the most literal examples of ‘art cinema’, Lech Majewski’s The Mill and the Cross brought a Bruegel painting to life with scrupulous period detail and tasteful CGI, and festival audiences were treated to an opportunity to see the final work of late, great auteur Raul Ruiz, the lavish epic, Mysteries of Lisbon. However, it was South Korean auteur Kim Ki-duk’s Arirang, winner of the BIFFDOCS prize, which perhaps most summed up the festival experience. Kim retreated to a remote country house with only his nervy cat for company following the harrowing experience of shooting his 2008 film, Dream, during which one of his actresses nearly died.

Arirang documents, mostly in close-up, the director’s many moods and thoughts about life, filmmaking and death, with a soundtrack provided by the director crooning the popular Korean folk song of the title. The intense self-reflexivity of these interviews is strongly reminiscent of Werner Herzog’s films, as are the director’s existential ruminations on filmmaking (“I want to confess myself as a director and a human being,” he says at one point). Along with some astute observations on the politics of contemporary international art cinema (he notes that official recognition at home tends to be catalysed by awards won abroad), Kim’s self-interrogation is shot through with his imagining of a persistent knocking sound at the door. While some critics have read this as mere paranoid fantasy, Arirang’s phantom knock could also symbolise the attuned antennae of both filmmakers and film festivals as they respond to, and make manifest, the cultural energies of the latent and the unexpressed.

Brisbane International Film Festival 2011, Nov 3-13, www.biff.com.au

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 20