the film editor: time & trust in the digital age

tina kaufman: henry dangar, screen editor

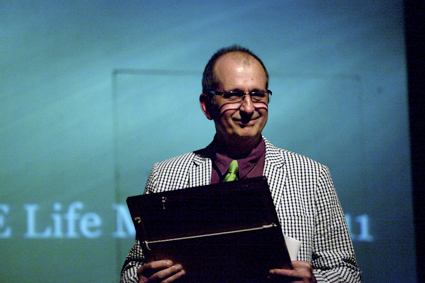

Henry Dangar is made a Life Member of the Australian Screen Editors Guild

photo courtesy ASE

Henry Dangar is made a Life Member of the Australian Screen Editors Guild

FILM EDITING HAS BEEN CALLED THE INVISIBLE ART, AND ITS ROLE IN THE PRODUCTION PROCESS IS OFTEN OVERLOOKED OR UNDERVALUED. I’VE BEEN GOING TO FILMS ALL MY LIFE, AND I THINK I KNOW WHEN A FILM REALLY WORKS, AND I KNOW THAT THIS HAS TO DO WITH BOTH THE DIRECTOR AND THE EDITOR, BUT THE WORK OF THE EDITOR, IN PARTICULAR, IS STILL MUCH OF A MYSTERY TO ME.

Bobbie O’Steen, author of a highly respected book, The Invisible Cut (2009), says that “editors decide what you see on the screen, and for how long you see it,” while legendary Hollywood editor Walter Murch says, “film editing is now something almost everyone can do at a simple level and enjoy it, but to take it to a higher level requires the same dedication and persistence that any art form does.” He also says that “Good editing makes a director look good. Great editing makes a film look like it wasn’t directed at all.”

Like most of the production process, editing has changed dramatically with digital technology. When renowned cinematographer Don McAlpine received the Raymond Longford Award at the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) Awards last month, he said that award had often marked the end of people’s careers, but he wasn’t going to let it mark the end of his; as the new electronic cameras are precise tools, and that computers “now allow us to tell stories that were once locked in our imagination—do you think I’m going to quit now?” he asked, rhetorically.

henry dangar: life member screen editors guild

Henry Dangar has worked as an editor in the Australian film industry for almost as long as Don McAlpine has been a cinematographer. He’s worked on Australian feature films from Stir in 1981 to Lucky Miles in 2008 and on iconic local TV drama from The Cowra Breakout in 1984 to Spirited in 2011. He was the initiating president of the Australian Screen Editors Guild and late last year was made a life member at the ASE Awards. Interviewing him after he’d received this honour, I asked him if digital editing had had a similar importance for him. He said that a whole world of possibilities had arrived with the change from physically editing the work print to editing using the computer. “Editing in the digital world is like opening a Pandora’s Box, which allows the `imagined’ to appear on the screen in a reasonably refined way. The possibilities are vast. It does take money, hard work and perseverance, but all is now possible, and very exciting.”

In many ways, he believes, “the creative work of the editor has become even more essential to the successful realisation of a script to the screen. Excellent crafting is to be treasured. However, it is a mistake to think that just by using the computer, good editing can happen quickly. I find the best work is done through reflection, consideration and review,” he says.

The Australian Screen Editors Guild is a very active organisation, with a lot of involvement from its 450 members nationwide. While NSW and Victoria are the two strongest branches, the guild has recently formed branches in WA and SA; ASE president Jason Ballantine says that “the guild is starting to hold events and to address issues that affect those local communities.” There’s a strong program of activities in the eastern states, including seminars, a free Avid course for members and screenings with Q&As. The new ASE website will be launched early in the year, and the guild offers a mentorship program and free membership to students to help develop their careers.

a fading future for apprentice editors

While most editors enjoy the changes digital technology has brought to the craft and to its role in the industry, the Guild is concerned that some changes have diminished the opportunities available to properly cultivate the next generation of editors. There are fears that the opportunity for junior editors to assist, collaborate with and learn from senior editors on the job has become very limited; while technical tasks can be learnt, editors believe that real skill comes through creative collaboration and the communication of the editor’s thought processes.

Henry Dangar agrees. “I do think it’s a shame that aspiring editors can no longer learn through an apprenticeship system—it’s just not in our vernacular anymore. Learning how to be an editor is really about the craft, about understanding just what it takes to realise a story and bring it to the screen. It’s something that is being lost in the rush to production, in the changes in budgets and schedules.”

However, he does believe that there are many media courses now that aim to fill that gap. “They offer a good foundation, but it’s practising the craft that’s crucial; and that’s where the apprenticeship system was so important, because craft can only be built up by practising, by making mistakes and learning from them. I used to have three Steenbeck editing tables—courtesy of Hans Pomeranz—and on one of those, several apprentices could be practising, but now budgets are structured so that it’s just the director and the editor and there’s no room for anyone else. I hope it’s not something we’ll be paying for in the future—if we’re not paying for it already. We don’t seem to have that culture of apprenticeship, of learning the craft, anymore—we’re just getting the films made.”

That said, Dangar believes that there are some good young editors coming through, and of course the thing about digital editing is that they can practice and learn on their own. “I’ve had students at an editing course that I’ve seen a year later, and they’ve made great strides working on their own,” he says.

increased shooting ratios: reduced editing time

There are other downsides to digital technology’s relationship to the editing process, especially in the incredible growth of shooting ratios, which can often be up to 100:1, compared to the more manageable 12:1 of the pre-digital age. The ease of shooting on digital has resulted in much more work for the editor, while tighter budgets and production schedules mean the same or less time to do the job. While the ease of working on the computer does alleviate this somewhat, tighter budgets are increasingly restricting the editor’s time on the film, preventing that collaboration through the whole production process (including the grade and the sound mix); it’s a significant loss, given that the editor is the only person who knows the picture frame by frame.

an editor’s life

Henry Dangar grew up in Armidale, coming from a family of farmers, but he couldn’t wait to get away after high school. He came to Sydney not knowing what he wanted to do (“I had no idea there was something called film editing,” he says), but through a friend got a job at ABC Radio in Forbes Street as a mail boy, before moving to ABC TV in Gore Hill, where he worked as an assistant editor for about four years. “The ABC, and life generally at the time, was very liberal and free, and for me it was very enlightening. Everything was done internally by different departments—drama, documentary, news—but it was possible to circulate between them, and work in music, light entertainment, on Countdown, on Aunty Jack—you were exposed to so much and became really resourceful. There was a freedom to make suggestions without it being frowned upon, and there were so many interesting people moving through the ABC, you were exposed to so many ideas. And people were so interested in film, rushing off to see new films, and to the film festival—even taking two weeks off to attend the whole festival. I met lifelong friends at the ABC—Geoff Burton, Nick Torrens…”

After four years there he left and went travelling in Europe for a year. “When I returned I just presented myself as an editor and worked freelance—some TV drama, some sound editing for Grundy’s and Robert Bruning. Then I met Stephen Wallace, who gave me my first real opportunity, editing his long short film, Love Letters from Teralba Road (1977) and then his first feature, Stir (1980). And from then on I was really working in film and that was what I had wanted to do. Meeting Stephen really started that for me.”

It’s been a long career, working on an amazing list of film and television work. Dangar has a good opinion of many of the films he worked on: Kiss or Kill (1997; he’s had a long and creative working relationship with Bill Bennett), Winter of Our Dreams (1981), Travelling North (1987); but of Stir in particular he has very fond memories. And having seen the restored print, he believes “the film holds up fantastically well, and that’s due to really good storytelling on Stephen Wallace’s part.”

For Dangar, it’s the pacing and the rigour of the storytelling that make a film work. “Films that I respond to most are ones that tell a human story, have a strong point of view—and lately I’m finding that TV series like Rake, My Place and Spirited do that. From my experience, when those things are in place, when the script is confident and the director is confident, then the whole thing is elevated, and for me it’s much more interesting, but you don’t get that all the time.”

I asked him what it is like working with directors, and he answered thoughtfully that “One has to speak honestly, but you have to find the right time. It’s truly a collaborative process, and it’s quite intimate. It’s part of the role of the editor to make the director feel confident, but you have to judge the right time to speak. You have to allow the director, especially when they’re also the writer, time to trust you as the editor. In many ways the editing room is a very private place—you develop a relationship in there that involves trust and responsibility, and that takes time. But it’s through that relationship that you can deliver something new and exquisite—those who are more prescriptive actually deny themselves the opportunity to do that. But even in those situations where the creative relationship isn’t as good as it could be, I try and find an aspect of the project that is worth exploring, and that helps me through. You need to really understand the world that’s being created, the story that’s being told, the milieu, the tone.”

A film that he particularly admires is The Social Network (2010). “I don’t know whether many people know that the editor of that film is an Australian, Kirk Baxter, and that he won the Oscar for editing it last year…I don’t think people realise how wonderfully crafted that film is, how it uses all the tricks it can to tell a story at a higher level.” In fact, Kirk Baxter has been working with the film’s director, David Fincher, and with another editor, Angus Wall, for some time. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and is nominated again this year for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011). He now lives in New York and mainly edits commercials, but says that he “feels very very blessed to have a partnership with Angus Wall and David Fincher.” He was disappointed that Fincher was not nominated for best director in this year’s Academy Awards.

Jean-Luc Godard says that “editing is the transformation of chance into destiny.” I don’t really understand that at all, but after talking to Henry Dangar, I think I understand just a little more about what it means to be an editor.

2011 australian screen editors awards

Award winners at the 2011 Australian Screen Editors Awards, held late last year, were: Avid Award for Best Editing in a Feature Film—Dany Cooper ASE for Oranges and Sunshine; Blue Post Award for Best Editing in a Documentary—Antoinette Ford for Girls’ Own War Stories; Digital Pictures Award for Best Editing in Television Drama— Martin Connor for Spirited, Series 1, Episode 2; Omnilab Media Award for Best Editing in Television Non-Drama—Denise Haslem ASE for On Trial, Episode 1; EFILM Award for Best Editing in a Commercial—Bernard Garry ASE for NAB 3 Year Olds; AFTRS Awards for Best Editing in a Short Film—Melanie Annan for Something Fishy; and the Level Two Music Award for Best Editing in a Music Video went to Matt Osborne for WA band Schvendes’ Lay the Noose.

RealTime issue #107 Feb-March 2012 pg. 19