a rash of male hysterics

keith gallasch: recent theatre in sydney

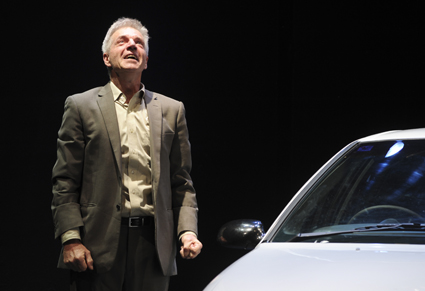

Bille Brown, Barry Otto, Josh Price, Edwina Wren, The Histrionic

photo Jeff Busby

Bille Brown, Barry Otto, Josh Price, Edwina Wren, The Histrionic

THE CONDITION LABELLED HYSTERIA HAS BEEN LARGELY RESTRICTED TO WOMEN (AS A NERVOUS DISEASE EMANATING FROM THE UTERUS MANIFESTING IN DIFFERENT PARTS OF THE BODY AS THAT ORGAN ‘WANDERED’). HOWEVER IN THE COURSE OF THE 20TH CENTURY AND INTO THE 21ST THE TERM HAS BEEN MUCH MORE LIBERALLY APPLIED AS THE NERVOUS INDISPOSITIONS OF MALES AND FEMALES HAVE BEEN RECOGNISED AS AT THE VERY LEAST SHARING KINDRED SYMPTOMS. IN THIS ARTICLE I’LL USE THE TERM VERY LOOSELY, APPLYING IT TO A COLLECTION OF RECENT PRODUCTIONS IN SYDNEY THAT CENTRED ON MALE FEARS AND FAILURES.

the histrionic

Hysteric and histrionic sit nicely together phonologically although they have discrete etymological roots (respectively, “of the uterus” and “pertaining to acting”). Hysteria entails behaviour exhibiting excessive or uncontrollable emotion. An histrionic personality disorder is one in which the subject insists on being the centre of attention, behaves as if before an audience, is emotionally volatile and excessively sensitive to criticism. The description fits the ageing Bruscon, the actor who dominates Thomas Bernhardt’s The Histrionic. A “national living treasure” who has fallen on hard times, Bruscon and his family of performers find themselves in an Austrian backwater. So tryannical is Bruscon that he thwarts his children’s performances and has driven his wife into silence. Director Daniel Schlusser admirably realises the near chaotic state that such a personality generates. Director and designer surround the performers with a mess of decaying theatre props while the action comprises endless interruptions, emotional outbursts, fractured rehearsals and, finally, the destruction of Bruscon’s grand creation by a competing local sausage sizzle and a storm.

Fate and a backward culture deal Bruscon a cruel blow, but he is his own worst enemy. Dangerously fragile, he feels his status to be constantly threatened. The solution? Perpetual self-aggrandisement, rampant sexism, the belittling of his sons and a desire to control his daughter to the point of incest—with just a hint of reciprocity from her, despite the bitterness of their exchanges. In one of the many delicious visual asides, the daughter sits sharpening a very long knife while her father rehearses. For Bernhard, The Histrionic was a depiction of Austria, culturally decrepit and authoritarian and embodied in Bruscon who, nonetheless, is allowed a few insights into his country’s failures, if never his own. Bille Brown creates a very believable and frightening Bruscon, the primal ruler of the herd, in a performance that braves the not always manageable tendency of the play to the monodramatic and the monochromatic.

death of a salesman

Colin Friels, Death of a Salesman

photo Heidrun Löhr

Colin Friels, Death of a Salesman

Willy Loman is another tyrant, if of a more domestic kind, but equally self-important and just as punishing of his sons, although more insidiously because it is his inflated belief in them which is destructive. His great achievements are his career and his sons, and he effectively loses them all, but the road to acceptance of his condition is long and hard, and incomplete. Colin Friel’s Willy is ebullient, even when tiring and feeling his age, quick to anger and to speechify, a man who almost dances to his death.

At the centre of an otherwise bare stage in Simon Stone’s production sits a humble, white 1996 Ford Falcon sedan, Willy’s proud possession. We know this is a cipher for the American cars so lovingly spoken of in the script, but a car is a car and Stone makes great use of it—it represents Willy’s travels, it’s a refuge and it’s a site for theatre magic as characters unexpectedly emerge from within its comforting womb. It’s also unpronouncedly and humbly phallic, a natural extension of the man, patted and fondled and admired. And when Willy no longer feels up to travel it becomes a place to die, not on the road, but in the yard. By centring the performance in and around the car, Stone creates a wonderful psychological seamlessness which, along with overlapping scene shifts, makes Willy’s visions of the past more palpable as they come over him like incipient dementia.

Like Bruscon, if without that man’s inherent sadism but blindly cruel nonetheless, Willy is beset by rage, despair and incomprehension and a desire for total control that is quite at odds with his place in the world. Willy is an arrogant performer, a fabulist, an histrionic and an hysteric whose failed dreams of being the ideal, loved worker and father take him to the edge of coherence and self-control. Bruscon is exemplar, critic and victim of the political failure of the state. Willy Loman is a passionate promulgator of the American Dream, enacting the state fantasy, imposing it on his family and destroying himself—victim and executor. Colin Friel’s performance is superb, supported by a very strong cast including Genevieve Lemon as Willy’s wife, Linda and there’s an excellent Biff from Patrick Brammall. Presumably because Stone, with designer Ralph Myers, has cast his Death of a Salesman as one man’s nightmare in which past and present deliriously mingle, there is no room for the final Requiem scene with Linda’s anguished eulogy—because it’s not part of Willy’s consciousness. Failing to find a way to incorporate the Requiem without sacrificing his vision, Stone takes the knife to Miller. Male hysteria?

old man

Zac Ynfante, Peter Carroll, Old Man

photo Heidrun Löhr

Zac Ynfante, Peter Carroll, Old Man

Matthew Whittet’s Old Man is a spare account of a young father’s struggle to achieve a sense of fatherhood—a kind of junior Death of a Salesman but without any sense of the dilemma entailing his career, politics, whatever. Sam (Leon Ford) feels distant from his two children, unable to manage their behaviour and alarmed that he might become, like his own father, an absence, someone who will be forgotten. Old Man is part dream play, in which Sam wakes to find his family gone, and part naturalism, where he acts on what his nightmare has taught him and goes in search of the father (Peter Carroll) who abandoned him as a child. Unlike Bruscon and Willy, Sam is not overtly controlling, but in his dream world he is a confessional storyteller, addressing us directly, increasingly panicky, suicidal even but rescued by his mother whom he cruelly and unjustly blames for his father’s desertion. This might be a dream world, but it is very telling, indicative of deep disturbance.

Perhaps then it seems a little too easy that in the real world Sam announces to his family that he has found his father and will go to see him. The scene with the father (Peter Carroll) is the play’s best. Carroll invests a simple man with complex, often unspoken responses. It’s clear to Sam there can be no meaningful reunion and perhaps that’s all he needs to know. However, at the play’s end, at the dinner table, Sam asks his family to never leave him. Ford plays it plainly but with just a touch of pleading that takes them by surprise, and an awkward silence ensues. Perhaps the good is that he has revealed himself to his family, the bad that his anxieties are still very real. Whittet doesn’t dig deep or at length in this short play, but the evocation of the emotional crisis of a very ordinary man in an intimately staged production is palpable.

die tote stadt

Cheryl Barker, Stefan Vinke, Die Tote Stadt, Opera Australia

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Cheryl Barker, Stefan Vinke, Die Tote Stadt, Opera Australia

Paul (Stefan Vinke) in Die tote stadt (The City of the Dead), Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s opera of 1920, has built an altar to his dead wife, Maria (Cheryl Barker), fetishising her golden locks and lamenting at length his undying love for her. A dancer, Marietta (Barker again), almost identical to the wife, enters his life and from that encounter springs a dream, in which Paul becomes her lover, inflicts cruelties on her and grows jealous as she flaunts her sexuality in the demimonde of which she is a part. He murders her and wakes to find himself much improved, eager to leave Bruges and its aura of death behind. What’s curious is the cure: the symbolic murder of his wife. In effect, he rids himself of her by transforming an idealised woman into a dangerously free spirit. In Bruce Beresford’s production for Opera Australia, Paul is admirably played by Vinke as dignified and tightly self-controlled before his breakdown commences. In Inga Levant’s production for Opera National Du Rhin (Arthaus DVD, 2001) he’s an utterly abject figure from the word go, unlikely to attract any woman’s interest let alone our understanding. If hysteria in opera has long been associated with diva roles, here it’s embodied firmly in the male—there’s an enormous amount of lovelorn, passionate and mad high-note singing which Vinke performs brilliantly. Cheryl Baker as Maria/Marietta meets similar demands with exuberance and sensitivity. The music is an odd blend of Viennese opera, Richard Strauss, Puccini and Korngold’s trademark melodic lushness. It’s an over the top opera in more ways than one, a borderline classic, but worth seeing for the singing above all—and the alarming male hysteria embedded in the libretto by the composer and his father.

bell shakespeare, the duchess of malfi

Lucy Bell, Lucia Mastrantone, The Duchess of Malfi

photo Rush

Lucy Bell, Lucia Mastrantone, The Duchess of Malfi

Bell Shakepeare’s brutally truncated adaptation of The Duchess of Malfi caricatures a great play, chronically reducing the time and space it needs to work its dark magic and superb testing of empathy. In an incomplete attempt to frame the work within the consciousness of Bosola—the hitman who turns just avenger of the Duchess he has murdered at the behest of her brothers— this version severely limits Webster’s fine distribution of complex characters across a large theatrical canvas. The performances are largely one-dimensional—even Lucy Bell’s otherwise nuanced Duchess is too girlish for too long; right to the bitter end in fact. The merging of Cariola and Julia is awkward. Ben Wood’s perpetually gruff, blokey Bosola undercuts the character’s politic role-playing art, Sean O’Shea’s Judge (Ferdinand in the play) is ragingly histrionic and David Whitney’s Cardinal perhaps aptly neutral—a touch of George Pell, I thought. The hysterics are, of course, the Duchess’ brothers, the Judge and the Cardinal, their motivation for not wanting her to marry and then having her killed is a mix of incestuous desire and powerplay. But in this case, it’s the adaptation that’s hysterical, as if maddened by a play that resists control, it all too hastily cuts to the plot chase.

As with Simon Stone’s Death of a Salesman, if you give the play a governing consciousness, something has to give. Here, Bosola is left alive at the end, a wiser man, but without facing the full consequences of the biddings of his conscience—death. He is pretty well reduced to a Morality Play figure, but he should be much more than the bearer of rhymed homilies. Likewise we need more time and space in which to live with the Cardinal and the Judge and their festering hysteria.

Sydney Theatre Company, The Histrionic, Thomas Bernhard, translated by Tom Wright, director Daniel Schlusser, performers Bille Brown, Kelly Butler, Barry Otto, Josh Price, Katherine Tonkin, Jennifer Vuletic, Edwina Wren, design Marg Horwell, lighting Paul Jackson, sound design, composition Darrin Verhagen, Sydney Theatre Company, June 20-July 28; Belvoir, Death of a Salesman, writer Arthur Miller, director Simon Stone, performers Colin Friels, Genevieve Lemon, Patrick Brammall, Steve Le Marquand, Hamish Michael, Pip Miller, Luke Mullins, Blazey Best, design Ralph Myers, lighting Nick Schlieper, composer Stefan Gregory, Belvoir Theatre, opened June 23; Belvoir, Old Man, writer Matthew Whittet, director Anthea Williams, performers Alison Bell, Peter Carroll, Leon Ford, Gillian Jones, Madelaine Benson/Mitzi Ruhlmann, Tom Usher/Zac Ynfante, design Mel Page, lighting Hartley TA Kemp, sound Stefan Gregory, Belvoir Downstairs, June 7-July 22; Opera Australia, Die tote stadt, composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, director Bruce Beresford, performers Stefan Vinke, Cheryl Barker, designer John Stoddart, lighting Nigel Levings, conductor Christian Badea, Sydney Opera House, July 3-18; The Duchess of Malfi, writer John Webster, adaptation Hugh Colman, Ailsa Piper, director John Bell, performers Lucy Bell, Ben Woods, Sean O’Shea, David Whitney, Matthew Moore, Lucia Mastrantone, designer Stephen Curtis, lighting Hartley TA Kemp, composer Alan John, sound design Steve Francis; Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, July 8-Aug 5

RealTime issue #110 Aug-Sept 2012 pg. 40