realblak

jane harrison

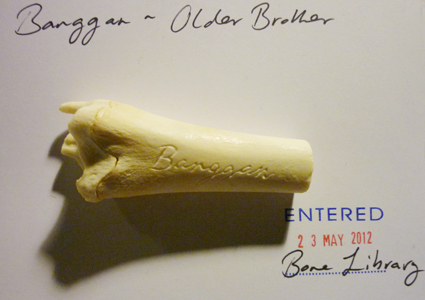

Sarah-Jane Norman, Bone Library

photo Annaki Kissas

Sarah-Jane Norman, Bone Library

AS EDITOR OF REALBLAK, LIKE A BOWER BIRD, I HAVE BEEN COLLECTING SHINY ITEMS, AND NOW PROUDLY DISPLAY THEM IN THE FIRST EVER INDIGENOUS PERFORMING ARTS EDITION OF REALTIME. OUR BOWER CONTAINS JEWEL-LIKE STORIES OF ARTISTS’ PRACTICES, FROM THEIR OWN PERSPECTIVE, THAT THEY HAVE POLISHED AND FUSSED OVER AND MADE PRECIOUS. ALL DIFFERENT, BUT WITH COMMON ‘BASE METALS’—OF PASSION, COMMITMENT TO COMMUNITY, A SENSE OF HISTORY OR CONTINUANCE OF CULTURAL PRACTICES, YET FORWARD THINKING. EACH OF THE ARTICLES, IN MYRIAD SHADES AND TONES, CONVEYS THAT STORY.

The stories demonstrate that we don’t want to be typecast or described or documented, or marginalised or exoticised. Our cultural expressions are not static—we morph and weave and are porous to other influences, but we hold our values; our cultural core persists. We are resilient. We are not homogenous. How could we be? Here’s a glimpse; Blak queens chatting, blood and bread in performance art, running away to the circus and the issue of a Blak aesthetic.

what’s happening?

This editorial is from my ‘bird’s eye’ view as a playwright. The third National Indigenous Theatre Forum (NIFT) held in Cairns, in August, was exciting, and it glinted with optimism. Beginning with an impressive list of achievements from the previous year, it was inspiring to hear of the initiatives that have come out of our forums—the idea for this edition, for one, and the emerging producers initiative being another (see Louana Sainsbury). The event naturally generated lots of ideas: about peak bodies and pathways and training and the need for advocacy and protocols and…not much talk about writing (from a playwright’s point of view).

One discussion at NITF did turn to devised plays, and who owns them, particularly when the devising group is made up of Aboriginal actors and the assigned writer is non-Aboriginal. The debate then segued to the issue of community permissions and when they should be sought, reciprocity and royalties and ways to divide them up fairly to give back to community. Overall, protocols were a burning issue at the NITF and they also smoulder in many of our RealBlak articles. Contrast this with the mainstream world where anything is up for grabs (wanna write a story about Warnie? Sure! Wanna write a story about teenage lesbian kidnapping murderers, based on a real story? Sure! Backlash? Huh? But if there is backlash, then it makes for good publicity).

For us, as Indigenous writers, unless we are stuck in a mould of only writing our own stories (in my case, how boring) then we need to write other stories—other people’s, made up stories and community stories—and these do require a process to be undertaken—a process that involves great sensitivity, protocols and permissions. Telling Aboriginal stories comes with a responsibility that none of us takes lightly. I am always struck, whenever you get a mob of blackfellas together, that we are anxious to ‘do the right thing’ by our communities, beyond furthering our own careers or feathering our own nests. But protocols and permission seeking are not always straightforward. Differences occur in the way communities operate in different geographic areas too. In this discussion—and it needs to be had—we mustn’t lose sight of the purpose of protocols. Wouldn’t that be to ‘do no harm’? None of us wants to harm our communities, I would say. We live in them, we have to deal with the consequences. (Unlike whitefellas, who can usually walk away). Challenging stuff.

who’s writing our stories?

While we are trying to grapple with the complex stuff of protocols, a quiet stealthful revolution is happening. White writers have slipped right past us and have jammed their Aboriginal themed plays onto a stage near you. I know, they have always written our stories. Alexis Wright laments the fact that non-Aboriginal people write Aboriginal-themed literature: “our histories have been smudged, distorted and hidden…” And now, too, in theatre. What was a novelty has become a steady stream. It’s not even a question of can they, because, mostly, it appears that they can (with caveats). But should they? And why do they? And are they doing it better than us? It seems to me more Aboriginal stories by non-Aboriginal writers are being produced than those that are written by us. Audiences are seeing them. And loving them, I guess.

who controls storytelling?

That brings me to another theme discussed at NITF: “What is Aboriginal theatre?” Not as straightforward as one might think. Is it an ‘Aboriginal play’ if it has an Aboriginal theme, Aboriginal actors, a white writer and a white director? (Before you think I am against white directors please note that my last play was sensitively and skillfully directed by a white director. Nor am I against collaboration. Or colour-blind casting.) What about a devised play with Aboriginal actors but where no ‘writer’ is listed? My point is, who is in control of the storytelling? Who owns the story? (Legally, the writer holds the copyright). And what about plays that are more clear-cut? Plays written by white writers, directed by white directors, programmed by white artistic directors and yet with Aboriginal themes and Aboriginal actors, who often get ‘tasked’ with being instant cultural consultants (just add ochre) during the workshop or rehearsal period, despite obvious power imbalances in those relationships? The publicity for the play features a bright-eyed Aboriginal actor looking deadly. But is it an Aboriginal play? Is it important who writes the story? Why care? Well, I do.

One part of this mix is that there are only four Aboriginal theatre companies; they might have funding to do one major production per year. At most, that means four playwrights may be commissioned in any given year. Not a whole lot of wriggle-room there. So, we want to get our plays on to main stages. Okay, there’s a dozen or so theatre companies around the country, who might program one ‘Aboriginal’ themed play per year. So if non-Aboriginal playwrights are writing those plays, where are our opportunities? Maybe there should be a moratorium on ‘Aboriginal’ plays written by non-Aboriginal people—unless they have been approved by a suitably qualified Aboriginal advisory group? And then branded as such, like a ‘Heart Smart’ tick: what about an ‘Aboriginal Approved’ or ‘RealBlak’ tick? Cos shouldn’t they be subject to protocols, too? Radical? Think about it.

In response to a key priority identified at the second National Indigenous Theatre Forum held in Cairns 2011 of the need for a space in which Indigenous performance makers and workers can critically reflect on their practices or their sector, Liza-Mare Syron, Andrea James and Alison Murphy-Oates approached RealTime to host RealBlak and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board to fund the venture.

I would like to thank all of the writers for their contributions and the RealBlak editorial committee for their wise council and encouragement; as well as the RealTime gurus Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter and team for their mentoring and support.

RealBlak is published with the support of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board of the Australia Council for the Arts.

RealTime issue #111 Oct-Nov 2012 pg. 2