more or less monstrous

jana perkovic: atlanta eke, monster body

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body

photo Rachel Roberts

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body

ATLANTA EKE’S MONSTER BODY IS A RADICAL AND BORDER-SHIFTING WORK FOR AUSTRALIAN DANCE, EVEN IF NOT SO IN AN INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT. THE ARTISTS WHOSE WORK FITS MOST CLOSELY IN THE LINEAGE OF MONSTER BODY—LA RIBOT, MATHILDE MONNIER, ANN LIV YOUNG AND YOUNG JEAN LEE—ARE RARELY IF EVER SEEN ON THESE SHORES.

But once an innovation happens, it loses its singularity in iteration. It thus cannot be appraised simply in the macho, military terms of ‘revolution,’ ‘innovation’ or ‘shock’: it becomes essayistic, formalist, a tool in a toolbox. But Monster Body is a carefully conceptualised and executed work, and loses nothing when the shock wears off. Instead, it provokes more thought, with greater clarity.

It is hard to see Monster Body without having first received warnings about its nudity, urination and feminism. On the surface, it is a confronting piece: Eke, swirling a hula hoop, greets us wearing nothing but a grotesque dinosaur mask. A series of classical ballet battements follows, morphing into rather more ordinary walking and crouching movements, accompanied by synchronised growls and shrieks. In the piece’s most notorious segment, Britney Spears’ “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman,” that Trojan Horse of post-feminist self-expression, blares as Eke placidly pees while standing upright, then rolls on the same patch of floor in gently erotic poses.

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body

photo Rachel Roberts

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body

However, the piece is neither overtly angry nor in-yer-face combative. Eke maintains dispassionate focus: the ambient lighting never creates separation between audience and stage, and the work seems to ask us to observe and judge, rather than rise up in arms. Notice, for example, how much more monstrous than the mask is Eke’s naked body—even though it is both a culturally docile (depilated in all the right places) and aesthetically ‘successful’ (young, toned, thin) body. We are more accustomed to seeing rubber animal faces than epithet-less nudity. Notice how unpleasant it is to watch a woman growl: inarticulate sounds and purposeless body movements need not be particularly extreme to cross a boundary of what a healthy woman may do with herself. The residue of the spectre of hysteria still lurks in our minds. Observe how very easy it is for a female human to appear monstrous, as if it has only been partially digested by our civilisation. And when a man in a hazmat suit appears to clean the floor or hand Eke a towel, observe how his very presence upsets the all-female stage, how ineffably strange it is to see this man neither represent, uphold nor fight for any kind of patriarchy.

Echoes of other artists appear reduced to bare essence. Eke and another female performer fondle each other’s bodies with a pair of rubber hands on long poles: this is Pina Bausch, but gentle, a moment that relies on our body memory of uninvited hands sliding down our calves for its emotional impact. Or, Eke fills her body stocking with pink water balloons, posing in her new, distorted figure, half-undressing and ending up with the stocking knotted into a bundle on her back, hunched under a heavy load of blubbery things that look, for all intents and purposes, like a pile of teats, or breast implants. The image echoes a whole canon of female disfiguration in art (I thought of Nagi Noda’s Poodle Fitness) as well as that of the misadventures of plastic surgery and of certain kinds of pornography, but it simply asks us consider what a human might look like once it has more breasts than limbs.

Monster Body, Atlanta Eke

photo Rachel Roberts

Monster Body, Atlanta Eke

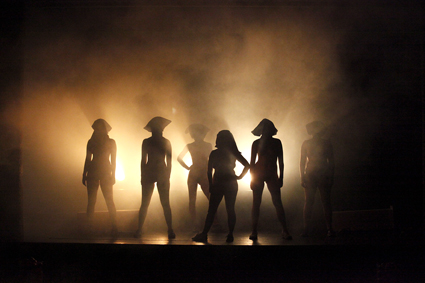

And then, in a musical intermezzo to Beyonce’s “Run the World (Girls),” hip hop empowerment, complete with an aggressive, ultra-sexualised choreography, is performed by an ensemble of variously-shaped girls, their nakedness made only starker by their running footwear and black bags on their heads. Drawing a link between the objectification and torture of people inside and outside of Abu Ghraib has already been made, with similar means, and perhaps more clarity, by Post in their Gifted and Talented, (2006), but Eke emphasises the vulnerability of these well-performing bodies, bodies that participate in their nominal liberation. Suddenly, Beyonce’s form of bravado displays exactly the weakness it is designed to hide. The painful powerlessness of this posturing is revealed by the sheer effort it requires, by the way it poorly fits a naked body, stripped of the armour of a hyper-sexualised costume.

As much as I tried, and despite everything I have read about it, I failed to see much of an all-encompassing exploration of human objectification in Monster Body. It seemed so clearly to draw a narrative arc of feminine non-liberation in present time, from the restrictive culturally condoned vulnerability of Britney to the restrictive culturally condoned strength of Beyonce. Its obvious interest in audience as a meaningful half of the performance also seemed to have fallen by the wayside, leaving a palpable void. However, as an essay on the physical restrictions of being a woman today, and a deeply thought-through one, it was very intellectually engaging. Shocking it wasn’t, but I suspect that was not its goal, either.

–

Dance Massive, Dancehouse: Monster Body, choreographer, performer Atlanta Eke, performers Amanda Betlehem, Tim Birnie, Tessa Broadby, Ashlea English, Sarah Ling; Dancehouse, Melbourne, March 22-24;http://dancemassive.com.au

RealTime issue #114 April-May 2013 pg. 30