sounds to dance to, with, against

gail priest: sound design in dance massive 2013

Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Conversation Piece, Lucy Guerin Inc

photo Ponch Hawkes

Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Conversation Piece, Lucy Guerin Inc

IT’S ALREADY BEEN NOTED IN SEVERAL OF OUR REVIEWS THAT MANY OF THE SOUNDTRACKS FOR SHOWS IN DANCE MASSIVE HAVE THEMSELVES BEEN MASSIVE. ALONG WITH SMOKE, STROBING LIGHTS AND NUDITY, SEVERAL SHOWS HAVE ALSO FOREWARNED THEIR AUDIENCE OF “LOUD MUSIC.”

These days the ubiquity of digital audio processing software makes it relatively quick and easy for the solo composer to create epic, symphonic pieces and dance has become the seeding ground for a kind of new electronic baroque. Often these soundtracks are masterful, but after seeing so many works in quick succession it is refreshing to experience collaborations between choreographers and composers or sound artists that attempt more subtle, conceptual and nuanced modes. An interesting anomaly in Dance Massive 2013 was the strange flashback to the days when composers were too expensive and choreographers cobbled together pre-made commercial tracks for their design. And why not—just to mix things up a little?

nostalgia for the signified

In Conversation Piece (which I saw in Sydney, not in its Dance Massive version) Lucy Guerin’s inclusion of songs such as Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds’ “Mercy Seat” performed by Johnny Cash or The Cure’s “A Forest,” seems pragmatic and devoid of irony. They are used to accompany the buoyant dances that curiously rupture the otherwise text-driven work and are clearly a “cheat”—they get us to where we need to go emotionally and atmospherically via their well established associations. However Guerin keeps things edgy, utilising the considerable skills of Robin Fox as sound designer to shift Conversation Piece towards darker places. The true complexity of the sound design is in the seamless manipulation of the iPhone technology as a multipurpose tool (as Apple has always wanted us to believe). The addition of the Garage Band rendition of Kylie Minogue’s “Come Into My World” (composed by Cathy Dennis and Robert Davis) is a stroke of quirky brilliance and serves to thematically integrate the idea of inner and outer worlds, personal and public soundtracks.

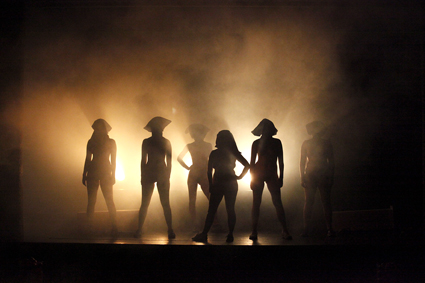

Monster Body, Atlanta Eke

photo Rachel Roberts

Monster Body, Atlanta Eke

In Monster Body, Atlanta Eke uses the most mainstream of commercial tracks, subverting them through that old postmodern strategy of juxtaposition. Britney Spears pipes “I’m not a girl, not yet a woman” while a naked Eke releases an arc of urine onto the floor. To Beyonce’s “Run the World (Girls)” Eke is joined by six other naked women of various body shapes to crump, jiggle and wobble very precisely through the grotesqueries of sexualised R&B dancing. Even the use of Ligeti (via Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey) hints at irony—the female body as cosmic unknown. In an over extended sequence, Eke parades in a body suit full of water balloons at the same time subjecting us to a relentless loop of revving motorbike engine—machismo at its sonic finest. In Monster Body, the music and sonic material hold the meaning in relation to which Eke’s body ventures definition.

haunted weather

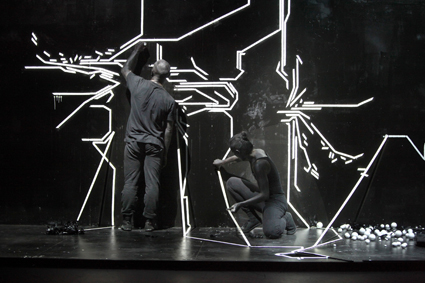

Antony Hamilton, Melanie Lane, Black Project 1

photo Ponch Hawkes

Antony Hamilton, Melanie Lane, Black Project 1

Discussing his approach to musical structure, John Cage said he sought to move “away from an object having parts into what you might call weather” (Composition in Retrospect, 1993). Antony Hamilton’s sound compilation for Black Projects 1—a series of tracks by European masters of electronic glitchy ambient Robert Henke, Mika Vainio and Fennesz—perfectly exemplifies this idea. This is not just because the soundscape consists of rolling waves of digital thunder and electronic static but rather that the music creates a space for the dancers (Melanie Lane and Hamilton) to simply inhabit. It is soundscape as landscape, not soundtrack, and it works well, allowing us to be drawn into the post-apocalyptic world while leaving space for the dancers’ actions to further shape and define it.

In Black Projects 2, however, the score, composed by Alisdair Macindoe (also a very fine dancer in Stephanie Lake and Lucy Guerin’s works), offers the complete opposite. Here the dancers are dictated to by the pulsing beats, as a six-headed creature shape-shifts and osmoses leading to a final holy cosmic epiphany. While well-produced and cinematic, the soundtrack offers little mystery, letting the dancers and us know where we are up to at all times.

big, bigger, biggest

Future Perfect, Jo Lloyd

photo Ponch Hawkes

Future Perfect, Jo Lloyd

Experienced on the first night of Dance Massive, Macindoe’s score indicated a trend in the many scores that followed. Perhaps paralleling the “loudness war” in commercial music production, it seems that many of the choreographers and their sound collaborators feel the need to make things bigger—more volume, more layers, more crescendos, more speakers. Siding with the critics of the loudness war, I wonder if something is lost in the process. I don’t just mean hearing (though that’s sometimes a possibility) nor even the crest or trough of dramatic range, but is it possible that these epic soundtracks have the effect of diminishing the bodily presence? Buffeted and propelled as it is by sonic forces, is the body losing its own agency, or space to be seen and read without the prompting of sonic signifiers? (Or have I been reading too much Yvonne Rainer?)

The soundtrack for Jo Lloyd’s Future Perfect by Duane Morrison feels close to subsuming the dancers and while transcendence is on the agenda, it feels a little more bullying than uplifting. Flavoured by 1980s synthesiser sounds the creators set themselves a difficult task. Starting at such a high sonic point, there’s little room for escalation either energetically or volume-wise throughout the piece.

Sandra Parker’s The Recording is an exploration of the disjunction between the body, gesture and mediatised performance, so allowing Steve Heather’s soundtrack to be bigger than the dancing is clearly a conscious choice. Composed from recordings of some of Australia’s and Europe’s leading improvising musicians, who are better known for their textural, pointillist sonorities, Heather’s score is surprisingly luscious and harmonically driven, becoming increasingly more romantic, even approaching the parodic with its Latino-lament conclusion. Does it mean that Parker succeeded in her exploration if I found the music more engaging than the physical performance?

Of course sometimes the hyperbolic soundtrack approach is perfectly apt as in Jethro Woodward’s score for Skeleton by Larissa McGowan. The work is about forces acting upon the body—both physical and cultural—and Woodward’s super energetic, highly fragmented score of smashing glass and sudden impacts mixed with computer game bleeps and cinematic howls, grunts and screams is masterfully constructed. He even allows for a quieter lyricism near the end, interestingly not paralleled by the dance which remains muscular, taut and edgy. The score is nerve janglingly relentless, yet utterly appropriate for the work.

Tara Soh, James Pham, Lauren Langlois, Leif Helland, Niharika Senapati, Alya Manzart, 247 Days, Chunky Move

Chunky Move’s 247 Days choreographed by Anouk van Dijk, a work about the highs and lows of youthful existence, is well served by the sound design by Marcel Wierckx (Canada/Netherlands). Gradually accruing detail from the almost imperceptible crackle of a vinyl record, underpinned by sustained chords, he works in live vocal elements from the miked-up dancers. Half-gasps, fragments of melody and shards of words are grabbed and effected, a bit of reverb here, digital stutter there, creating the sense of an ‘internal voice.’ The piece culminates in a choral epiphany, voices delayed, pitch-shifted and overlapped to form a massive chorus, but somehow it just doesn’t quite reach the peak to which it aspires, or perhaps it does so too rapidly. While much of the spoken text feels naïve, the more abstracted vocal play provides a cohesion to both the soundtrack and the work overall.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a vast soundtrack but perhaps what is beginning to perplex me is that the “bigger and louder is better” approach is in danger of becoming the default setting for contemporary dance, not only in the mainstream but also the independent sector. (Is this the place to mention that, one female “sound theorist” aside, all the composer/sound designers in Dance Massive were male?) While there’s no doubt that it is effective/affective, is this approach conceptually engaging?

dancing dialogues

Alisdair Macindoe, Sara Black, Dual

photo Ponch Hawkes

Alisdair Macindoe, Sara Black, Dual

For those seeking a deeper investigation into the relationship of sound and the moving body several of the smaller scale works offered the most satisfaction. Robin Fox’s sound for Stephanie Lake’s Dual is definitely of the epic loud variety; however both dance and music explore a clear structural principle—Part 1 = A, Part 2 = B, Part 3 = A+B. The correlation between action and sound develops a complexity due to the absence or rather the implied future presence of the other half of the dance and music. For example, in a section of her solo Sara Black lies face down on the floor slowly and gracefully extending her limbs while her soundtrack berates her with seemingly inappropriate harsh stabs. When the duo is complete, we see that the soundtrack at this point more clearly reflects Macindoe’s actions rather than Black’s reaction as he pulls and prods her. It’s a simple conceit but offers a fascinating depth in its execution.

Natalie Abbott, Sarah Aitken, Physical Fractals

photo Ponch Hawkes

Natalie Abbott, Sarah Aitken, Physical Fractals

Physical Fractals also worked with bare-boned simplicity, effectively marshalled by sound designer Daniel Arnot. Natalie Abbott and Sara Aitken’s rhythmic repetitions make sounds in the space which are captured by eight microphones, placed with heads hard up against the floorboards. The predominant sounds are footfalls and breaths, delayed to make rhythms which radiate out from the initial action. Sometimes the sounds of the actions are captured and continue after the bodies have ceased to move, playing with our perceptions and expectations. At one point sound becomes the dominant character of the piece as the dancers swing live microphones like lassoes just above the audience producing a ferocious roar which in some deft looping trick continues long after the dancers are still again. What is particularly refreshing is how raw and unaestheticised the sounds themselves are, the only decoration found in the beats made by delay or the ever-present hum of sound and light leads interfering with each other. While this use of action to create the sound score is not new, it’s the purity and thoroughness of this exploration, the conceptual rigour in both dance and sound design that makes this work impressive.

Tim Darbyshire’s More or Less Concrete works with a similar premise to Physical Fractals but pushes it to its ultimate conclusion. The three dancers are closely miked, every movement, mumble, rustle, breath heightened for the audience via the headphones they are invited to wear. Here sound is not so much a by-product of movement but rather the movement seems decided by the sounds they will produce. The gentle “shhhhh” of bodies against the floor, the “phhhhhhh” of bodies rubbing against each other in polyester overalls, the slap of hands hitting the floor all call for the body to form odd shapes and perform actions that are the dance itself. Only occasionally is an effect added, some reverb or ring modulation to expand an action further into the space. Where Physical Fractals achieves a symbiosis of sound and movement, More or Less Concrete creates a complete synthesis.

Finally on matters of integrated sound and action, Ashley Dyer’s Life Support (made with a long list of collaborators including Sam Pettigrew on ‘sound and objects’) also deserves a mention not so much for its integration of body and sound but rather as an inhabited sound and light installation. Above an ominous and insistent hum the smoke machines used to fill the increasingly claustrophobic space provide a utilitarian and deeply disturbing soundtrack. The sonic highlight is an all-too brief performance by a smoke ring orchestra—upturned speaker cones with buckets attached emit rough farty sounds, the vibrations sufficient to puff air for the creation of smoke rings. I would like to see/hear a whole concert of that!

festival compression

Tony Osborne, Life Support, Ashley Dyer

photo Rachel Roberts

Tony Osborne, Life Support, Ashley Dyer

Of course it’s a little unnatural to experience so many works in such a short amount of time and it can lead to unfair comparisons, but it does provide a contour map of ways in which dance and music are developing. Compared with works in Dance Massive 2011 the grand cinematic soundtrack remains a constant, but this year we see the re-introduction of the mix-tape mentality and also a shift from the live instrumentalist to the performing audio engineer which allows for in-depth explorations into concrete, less decorative sounds in space. In these latter works we see not only a rigorous investigation into the relationship of sound and the performative body, but also an extension, particularly for a more mainstream audience, of the very definitions of music. Sam Pettigrew (sound and smoke-ring master in Ashley Dyer’s Life Support) suggested to me that during festivals like this there’s a great opportunity to put on an über-gig, bringing the purely audio work of these innovative composers and sound artists to a whole new audience. One for Dance Massive 2015?

–

Dance Massive 2013, Arts House, Dancehouse, Malthouse, March 12-24, 2013; http://www.dancemassive.com.au

Due to various constraints several shows in Dance Massive were not able to be addressed here: Marrugeku’s Gudirr Gudirr, Lee Serle’s P.O.V., Matthew Day’s Intermission, Hannah Mathew’s Action/Response, and Dance Exchange’s dance for the time being – Southern Exposure.

RealTime issue #114 April-May 2013 pg. 34