From the archive to a new gay baroque

Erin Brannigan: Montpellier Danse 2013

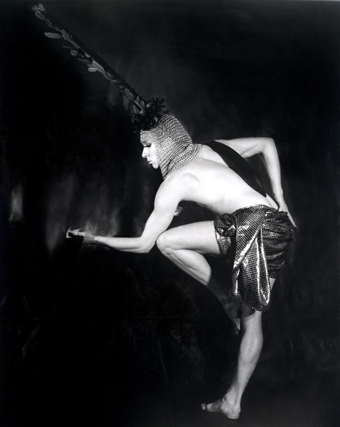

Francois Chaignauld

photo Odile Bernard Schröder

Francois Chaignauld

Despite some claims for a ‘palimpsest’ approach through a focus on dance history, I couldn’t really think of this year’s Montpellier Danse festival as a whole, but rather as a series of discrete works. That said, director Jean-Paul Montanari is a well-informed guide for his survey of a history that is honoured in Europe and the USA in a way that genealogies of Australian dance certainly are not. The staging of Maguy Marin’s classic, May B (1981) and a chronological trilogy from Trisha Brown spanning the years 1989-2011 showcased the ability of this festival to draw from the archive with panache.

Maguy Marin

May B is an important work linking French contemporary dance to the country’s mime tradition. Using clown-like facial and body prosthetics and with clay covering their skin and clothes, the characters in the piece are dusty remnants of a forgotten village. They move in rhythmic unison and follow one another’s behaviour, whether marching, dancing or barking garbled noises. This pattern is broken when two female characters spar, a birthday cake is shared and the group travel, leaving the stage from the front, climbing awkwardly down into the stalls and reappearing upstage. Selfishness is a key theme but also care and loneliness —a study in universals played by a very committed cast and with a compelling use of regimented chorus work.

Corner Etudes, Emanuel Gat

Emanuel Gat

Emmanuel Gat, the choreographer-in-residence at this festival, provided the public with access to his choreographic process across a week as he devised the last part of a quartet of ‘etudes,’ Part 4: The Surprising Complexity of Simple Pleasures. This strategy follows his very Cagean interest in opening up composition to the contingencies of real life. (Gat has been writing about his choreographic approach on his website.) We joined him at the last rehearsal, but some members of the public had followed the whole week and the exercise appeared to be very successful in building a relationship with his audience.

The final work, Corner Etudes, builds on Brilliant Corners which I saw in 2011, continuing Gat’s interest in music as a compositional point of departure. The audience was invited onto the stage of the cavernous Theatre Berlioz in Montpellier’s Corum for the first three sections: a group, duet and quartet. Sitting around a square of light, the perspective and ambience was dazzling. The duet between Michael Löhr and Francois Przybylski included an original song performed by Przybylski and the quartet was a delicate study in collapsing spaces between bodies. For The Surprising Complexity… the upstage back wall was flown up in a grand gesture and a seating bank appeared facing out into the absent audience. In rehearsal we witnessed the atmosphere of egalitarianism as Gat does, as he states, ‘let the work happen.’

Mature artists (including Australian Genevieve Osborne) with diverse technical backgrounds, amazing facility and creative investment had each developed movements to a song of their choosing. In composing these voices into a single work, Gat shifts each of them between dancing and singing and layers material by bringing one song to the front and having the dancers adapt to this ‘score.’ He then adds a second song that gives them a choice of temporal structures to follow. He subsequently adds and subtracts dancers (where in other sections these choices seem to be ‘called’ by the dancers as they name someone and cluster to them), ending this section with Przybylski and Milena Twiehaus collapsing the space between two solos so that they are dancing on top of each other, with arms stretching through armpits and scraping slowly across necks. This final solo of the piece was quiet and mesmerising. The movement choices of the dancers are often intriguing and while the final composition has something in common with William Forsythe’s clustering of energy within groups and across space in an ebb and flow or breath-shaped pattern, this movement is of a more terrestrial order with everyday gestures included and bodies more firmly connected to gravity. The inter-relationships are also more intimate and gently confronting.

Trisha Brown

A single performance from the Trisha Brown Dance Company delivered a survey of works from across her mid- to late career when she began to choreograph with music: Astral Convertible (1989), If you couldn’t see me (1994), and I’m going to toss my arms—if you catch them they’re yours (2011). The remarkable thing about the 1989 piece is that it looks so like Cunningham with its Robert Rauschenberg set and John Cage score, its silver unitards with bizarre ‘fanny skirts’ on the girls differentiating the sexes, and some very shape-based movements. This reasserted a continuity in American modern dance for me that has been smoothed over by the intensely detailed analysis of that nation’s dance history which emphasises the important differences in what is fundamentally very similar.

The dancers were surprisingly young and had an attitude of calm non-fussiness, delivering movement material with minimum effort and an ample softness. The trademark little skips, lightning changes of direction, oddly awkward partnerings and leaps, and deceptively simple compositions of the group in space were all operating across the three works. Arms were kept to a minimum with an emphasis on the trunk of the body initiating movement and the limbs following on. Brown’s interest in the basic mechanics of the body and real effects of gravity and weight were in evidence as the simplest moves were performed with clarity and delicacy. It was a thrill to see Brown’s work live, especially as she is retiring from the head of the company due to failing health.

Cridacompany

This French company’s piece, Manana es Manana, begins with three men bent over a pile of potatoes, tossing them into the centre of the mound over and over with an amplified soundscape of the puttering noise produced. These simple means set the tone for a performance that shows what a body can do in simple, funny and awkwardly moving sequences. The only woman of the quartet is a thin, lanky, beautiful but morose character who attempts to do her hair and put on her shoes while the men shake her arms and legs to tragi-humorous effect. The three men then toss her around like a plank of wood in inventive and risky ways—dropping her and clapping before catching her, balancing her on their shoulders and turning themselves around while she stays where she is. A homemade video shows them in the Alps and one of them free-jumping off a mountain from a dizzying and alarming camera viewpoint. It’s hard to describe some sequences to give due credit. One performer juggles with hacky sacks while changing clothes, accompanied by a voice-over pronouncing how good he is. The humble somersault is worked into intricate weaving patterns and simple lugging becomes a hefty ‘ballet’ as the men move each other like sides of meat. It’s simple circus delivered with compositional simplicity and a lot of personality.

Francois Chaignaud

Dumy Moi was my last show in Montpellier and a cracker. I had heard about Chaignaud’s partnerships with Cecilia Bengolea including an expressionist dance modelled on early 20th century work and a duet performed with glass dildos in their bottoms. But nothing could have prepared me for this work. Chaignaud emerges from the dark as a massive shape: he is wearing what looks like a traditional Asian dancing outfit with a hoop of feathers attached at his waist and bare bottom showing, wings and chest plate of gauche sparkly decorations in plastic, a headpiece of feathers and shiny arm and leg plates. Made up like a Chinese opera performer and singing deeply like a Japanese Noh actor, he performs simple turns and promenades. This section ends with spinning and I wonder where he can go from here wearing that outfit. But the next section sees him extricate himself from it with style, singing in-between in a falsetto voice—this in itself is astounding. Combined with the series of outfits and immaculate dance moves his performance, experienced in the round and at close proximity, is a tour-de-force.

The next outfit comprises a hat of full-sized birds with a long plume of feathers curling around Chaignaud. A feathery jacket completes the transformation and he jumps delicately and high. This is the beginning of his most choreographic section with impressive held arabesques and deep second pliés, delicate running sequences and slow walks balancing on demi-pointe. Chaignaud adds to this outfit a five-foot wooden headress and continues with his dancing and singing in the most awkward postures. It felt like a salon performance for the rich and spoilt (he calls it a ‘recital’): a baroque treat and a must for the next Sydney Mardi Gras Festival.

Montpellier Danse 2013, Montpellier, France, 22 June-6 July

RealTime issue #116 Aug-Sept 2013 pg. 28