Resisting erasure

Vincent Leveridge: Ghost Citizens: Witnessing the Intervention

Janelle Low, Ghost Citizens

In recent years contemporary Indigenous art has focused on questions of identity, often personal identity, but with this exhibition, Ghost Citizens: Witnessing the Intervention, we see the return of broader political art about Indigenous Australia.

Along with a number of relevant extant works, the exhibition presents new artistic responses to the “intervention” into Aboriginal communities in 2007, currently named the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), a legislative stripping away of the rights of a minority without regard for international Human Rights conventions along with suspension of Australia’s Racial Discrimination Act.

Ghost Citizens began as an intervention itself, shadowing the 2012 Sydney Biennale. By ‘supernatural decree’ the opening night party coincided with the passing of the legislation to extend the NTER—shockingly for the next decade, a young lifetime. Ghost Citizens, offering Indigenous artists from remote regions peer support, aimed to alert visiting international artists to the fact that not all Australian artists had equal rights. The Biennale curators and many artists attended talks by Eva Cox and Craig Longman from the Jumbunna Centre as well as Hetti Perkins’ launch of Artlink magazine’s “Indigenous Indignation” at Cross Art Project gallery. Income management and other controversial elements can now be applied to any part of the country—including places like Shepparton in Victoria—at the discretion of bureaucracies.

Speaking directly about the role of art in the current political climate, the exhibition draws on works by eight Aboriginal and five non-indigenous artists. Together they represent vast experience in the representation of contemporary Indigenous culture.

During a panel discussion accompanying the exhibition, curator Djon Mundine spoke of cycles in the process of recognition and engagement between white Australia and the Indigenous peoples with attempts at recognition beginning and building only to collapse as the possibility of recognition gets closer. This is followed by a period of retreat and non-recognition when the Indigenous become ghosts again—invisible, avoided and obscured from public gaze.

The bleak and barren Basic Card (2011), consisting of a blow-up banner and associated business cards from Brendan Penzer, displays the government’s new stamp of identity/non-identity. The bureaucratic imposition is emphasised in Penzer’s installation of a collection of sanitised literally white and “approved” supermarket food items and the print-out of the rules that welfare recipients have to live by. It’s a white bread and sugar diet.

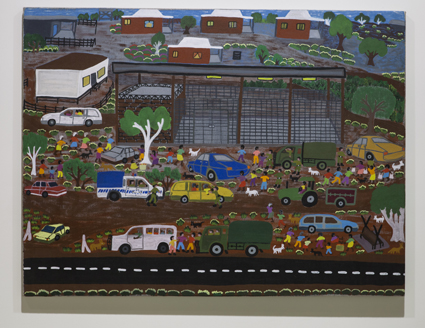

Kylie Kemarra, The Intervention at Ariparra Store, via Sandover Highway, Utopia Community, NT 2010, Ghost Citizens: Witnessing the Intervention

Counihan Gallery, Melbourne

Responses from Aboriginal artists living in remote locations include a painting by Kylie Kemarra titled The Intervention at Ariparra Store, via Sandover Highway, Utopia Community, NT 2010. Here Kemarra depicts troops and trucks herding people into a cage-like store area. Amy Napurulla and Sally MA Mulda paint ground level views of trucks bringing in the portable homes and offices for the new overseers.

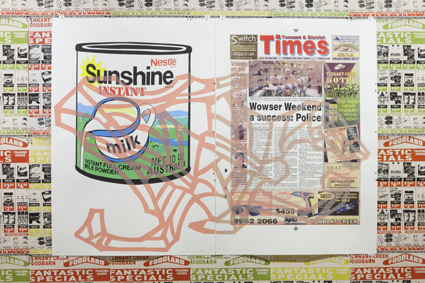

The banal is made large in Alison Alder’s mural of grocery prices in newspaper ads from the Tennant Creek grocery, the only supermarket in the remote town. The ordinary looms large like a wall in the mechanics of daily living as the ads are overlaid with pages from the local newspaper that treat the Intervention as a non-event. Jason Wing’s self-portrait behind a government card labelled “Criminal” references the surveillance and digital monitoring [that form part of the intervention].

Therese Ritchie emphasises stigmatisation by stitching the Basic Cards into a gown modelled by Rachael McDinny in her large colour print All dressed up and nowhere to go (2012). Fiona McDonald’s text on landscape prints of Kurnell and of Captain Cook speak of inclusion and exclusion while Bindi Cole’s deeply ironic photographic portraits of people with blackened faces refer to a broader and often rejected Aboriginality.

The laconic left is represented by Chris Chips Mackinolty’s witty new road signs for the NT: And there will be no dancing (2007) and National Emergency Next 1,347,525 km (2007).

Video works include Fiona Foley’s Bliss (2006) featuring haunting images of poppies, referring to the opium supplied to Queensland Aboriginal communities [at the turn of the 20th century] creating addiction and [thereby] control. Other video works contain excerpts from dialogues between activists and artists at Sydney’s Cross Arts Projects.

Ghost Citizens is a collection that documents experiences of marginalisation, of people moved or pushed further to the fringes of Australian society by deliberate government bureaucratic experimentation. It also offers a view into what may be at the fringe of all our political worlds, a portent of wider political futures.

For Indigenous people living in remote areas with little political power, the intervention means discrimination and increasingly segregated and controlled modes of consumption; out of sight and out of mind—ghosts again.

Ghost Citizens: Witnessing the Intervention, curator Djon Mundine with Jo Holder, Counihan Gallery, Melbourne, 16 May-16 June; The Cross Art Projects, Sydney, 21 June-21 July

RealTime issue #116 Aug-Sept 2013 pg. 54