The two voices of Mayakovsky

Keith Gallasch: interview, Michael Smetanin, composer

Michael Smetanin

courtesy the artist

Michael Smetanin

Ever-adventurous Sydney Chamber Opera is about to premiere Sydney-based composer Michael Smetanin’s Mayakovsky to a libretto by poet, novelist and critic Alison Croggon. Their subject offers these artists rich material—a life complex and confounding, revolutionary but, even in the revolution’s terms, rebellious.

Pre-revolutionary and Revolutionary Russia were culturally fecund times, abounding in new ideas, movements and artistic invention. Radical experimentation in all artforms gave revolution succour and inspiration amid horrendous power play and bloodletting until by at least the late 20s when it was absorbed into the State’s mainstream or more often banished—bodily to Siberia or bureaucratically to the outlawed, coverall category of Formalism. Some artists faded into alcoholic despair, some played by the rules or appeared to (as is alleged in the case of Shostakovitch), some were imprisoned or murdered, others suicided.

The poet, playwright and poster artist Vladimir Mayakovsky, who shot himself in 1930, was one of many artistic leading lights in the 1910s and 20s and one of the most famous. His commitment to the spoken word in his public recitations with his deep baritone voice, bardic rhythms and the vividness of his writing—prodding, assertive, tortured, rich in imagery cosmic and streetwise—made his art accessible and bracing. This, we must remember, was a time when in Russia and across the Western world, artists were self-declared prophets, socialist or fascist, waving the wands of new technologies, conjuring new futures, leading the charge as an avant garde, but ever espousing the fundamental power of the Word—spoken, sung, propagandised—and Word as Image—typographically radicalised and collaged in his collaborations with Rodchenko and Lissitsky. This was Mayakovsky’s art.

Agitator and martyr

Mayakovsky’s friends described him as gigantic, anarchic, volatile. Maxim Gorky recalled meeting the young poet: “I liked his verses and he read very well: he even broke into sobs, like a woman, and this alarmed and disturbed me. He complained that a human being is ‘divided horizontally at the level of the diaphragm.’…He behaved very nervously and was clearly deeply disturbed. He seemed to speak with two voices, in one voice he was a pure lyricist, in the other sharply satirical. It was clear that he was especially sensitive, very talented, and—unhappy.”

He also saw himself as a martyr. Marjorie Perloff describes Mayakovsky as a “poet-saviour” in his poem “Cloud in Pants” (1915): “I’ll drag out /my soul for you /stomp it flat /so that it’s giant /and, blood-soaked, bestow it—a banner.”

His most famous poem Listen! is finally reassuring (“Listen, /if stars are lit, /it means—there is someone who needs it.”) but only after first conveying the abject horror of a cosmos without stars: “in the swirls of afternoon dust, he bursts in on God, /afraid he might be already late. /In tears, /he kisses God’s sinewy hand /and begs him to guarantee /that there will definitely be a star. /He swears /he won’t be able to stand /that starless ordeal.” Smetanin’s librettist Alison Croggon (this is her fourth work in collaboration with the composer) says that she “picked up the poem Listen, and extended it as a metaphor through the libretto” (Limelight Magazine, 13 August, 2013). As you’ll read in the following interview, Michael Smetanin has made use of Mayakvosky’s actual voice.

Mayakvosky’s fragility is everywhere evident in his poetry (and the upheavals of his life—centred on the torturously prolonged emotional ties to “the muse of the Russian avant garde” Lili Brik, who rejected him after 1923) alongside self-aggrandisement, self-deprecation and abjection.

The poet’s voice

Appropriately for an opera about Mayakovsky, this emotional tension is felt strongly in respect of his voice. His pride in it is evident in lines from a variety of poems: “the velvet of my voice,” “then shall I speak out /pushing apart with my bass voice the wind’s howl,” “I shake the world with the might of my voice,” “I /the most golden-mouthed /whose every word /gives a new birthday to the soul,” and “If /to its full power /I used my vast voice /the comets would wring their burning hands /and plunge headlong in anguish.”

However, in “Violin and a little nervous,” the deep baritone, “cried out, “Oh, God!” Threw myself at her wooden neck, “Violin, you know? We are so alike: I do also Shout— But still can not prove anything either!”…“You know what, Violin? Why don’t we—Move in together! Ha?” Often in Mayakovsky we sense the uneasy co-existence of two voices, two personalities, and no less in his political life.

In “At the Top of My Voice,” he expresses his pain at having to submit himself to the dictates of the Revolution, “…I subdued /myself, /setting my heel /on the throat /of my own song.” Nevertheless, as he did until his death, he commits himself to Communism, even imagining himself raising high his Bolshevik Party Card—one he never had. As Gorky observed, Mayavosky was a man two voices; they gave his poetry power and personality and reflected the painful dialectic of his life and politics.

I met Michael Smetanin at the Sydney Conservatorium where he teaches composition and music technology. The composer’s career includes two operas with Alison Croggan, The Burrow (1994) and Gauguin (2000), his superb music for the wonderful 2000 Adelaide Festival production of UK playwright Howard Barker’s eight-hour The Ecstatic Bible (directed by Barker and Tim Maddock) and a host of idiosyncratic orchestral and chamber works of great power.

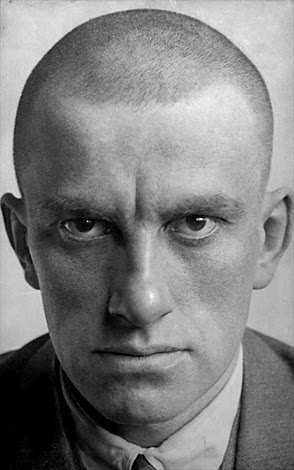

Vladimir Mayakovsky

The interview

What attracted you to write an opera about Mayakovsky?

Mayakovsky is close to my heart in terms of my family background, which is Russian. It goes back a good way to when I discovered books on Mayakovsky at the Soviet Bookshop down the Haymarket end of Pitt Street back in the mid to late 80s.

I didn’t really know about Mayakovsky. He’s well known by schoolkids in Russia. Stalin said that Mayakovsky was his favourite poet but didn’t understand his poetry and really despised him. I think the fundamentalist regime and the fundamentalist apparatchiks didn’t like Mayakovsky and tried very much to keep his lifestyle under wraps because he was not a good example for the worker. Pre-Revolution Mayakovsky and other artists were under the impression that the Revolution would bring them a new freedom for intellectual exploits. But in actual fact, we know it was the opposite. It was not so bad under Lenin but when Stalin took over it was. Stalin was already looking over Mayakovsky’s shoulder before Lenin was gone. He was already a marked man.

If Mayakvosky hadn’t suicided, perhaps he wouldn’t have lasted anyway.

Well, it depends which Russian you speak to whether they think it was suicide or the NKVD, the precursor to the KGB, got him. It might have been a hit or it might have been suicide. Mayakovsky certainly did attempt suicide earlier in his life, even in his teens. So he was a big sack of contradictions, which is interesting.

Are those contradictions just one thing or everything that grabs you about him?

A lot of people say to me, well you’re a big sack of contradictions yourself. That’s me. I think that I kind of—I know I’d never met him and all that and he was dead before I was even born—but I had an almost spiritual connection with the man. And then seeing some of his films…He was a strong, robust type, a handsome guy, smoked like a chimney, drank copious amounts of whatever he could get his hands on, womanised a lot. Although an important feature in the opera is the ménage a trois he had with Lili and Osip Brik, I don’t think it was ever three-in-a-bed stuff. And once again, it depends on which Russian you speak to as to whether you believe or not that Mayakovsky might have been a convenience for Lili to make her own existence more tolerable. Being so close to him she did get visas to travel abroad. Just her connection with someone so famous was obviously going to get her some favours.

How have you focused this interest in the contradictions in the opera? Obviously they offer a lot of opportunities.

It’s very rich ground. The first photograph of him I saw was one in which he had a shaven head. So he looked like a 1920s Punk to me. All this strength and virility makes for a fairly strong score. There are tender moments—a love scene. There’s a lot of electronics in the score. All of my operas have them to some degree but this has much more. There are some eclectic moments, the little quotation, for example, of a Russian tune about a Christmas tree in Scene 3, which is a Futurist Christmas party where the apparatchik Svedova is being taunted by the other guests. It’s an electronic scene.

There are various versions of the attitude towards Futurist sound in the 20s and what it was: what actually is the sound of the future? In Mayakovksy’s play The Bedbug (1929) there’s a Phosphorescent Woman character who says we’re going to travel to the future 100 years from now, which could have been 100 years from the date that Mayakovsky recorded his poem Listen!, which is this year. So [in the score] it’s a combination of these things—almost like Futurist noise music with metal sheets and electronic music’s pure sine and sawtooth waves.

Vladimir Mayakovsky

photo Alexander Rodchenko

Vladimir Mayakovsky

This was the era of the theremin, wasn’t it?

Yes. At the beginning of the work are sounds using those pure waves, which conjure up the notions of futuristic electronic music, but of the 1920s and 30s, very, very early stuff.

What about the fragility of Mayakovsky’s character? He was incredibly self-aggrandising and could be very abject on the other hand.

Yes, there’s a lot of that in the libretto. Mayakovsky’s alter ego is a character in the work, called The Author, no name, nothing. The Author is a tenor and Mayakovsky has to be a baritone. So there’s a kind of duality there but they’re one and the same. That’s addressed in the text and the interaction between the two characters is musically underpinned where it’s necessary in the dramatic flow of the work.

I read you did spectral analysis of a recording of Mayakvosky’s voice.

[Another aspect of] technological newness, if you like, was to include in the score Listen! (or Poslushayte!), a famous poem by Mayakvosky. Every Russian knows it. He did a recording of it in 1914. It’s 52 seconds long and unfortunately the first couple of words are missing from the recording. The first word is Poslushayte! and it is used again at the end of the poem so I’ve just assumed he said it the same way. The spectral analysis of that poem I’ve stretched out for the length of the opera. So the spectral analysis of Mayakovsky reading his own poem provides the harmonic pathway for the entire opera.It’s not intelligible then as spoken text, but as sound?

You can take the spectral analysis and have a piano score printed out from it. And the piano score also has a rhythm. So when that rhythm is stretched out those time proportions are apportioned to and through the libretto and to carry it. And the actual pictures of the spectral analysis are used to inform the harmonic pathway.

Did this pose a challenge for your librettist, Alison Croggon, to write to it?

The challenge was for me to…

… create the spaces?

Yes. There were at least 11 drafts of the libretto before the final draft which was edited together after I’d completed the score—a few words changed here and there, that kind of thing. So the harmonic direction is imbued by Mayakovsky’s own voice. This is actually explained at the beginning of the opera. There are projections of some texts by Mayakovsky read by the actor Alex Menglet and the actress Natalia Novakova reads the part of the Phosphorescent Woman. Then a little while later there is an explanation read by Natalia as well—of the fact that a spectral analysis made of the 1914 reading shows that C Sharp is the fundamental of Mayakovsky’s voice. Using a different application to do the analysis, it could have given me a C Natural, perhaps—who knows? But that C Sharp appears a lot. It opens the opera.

Are there other characters?

There are six singers. Mayakovsky, Lili, The Author, a high baritone who sings Lenin and Stalin and a few chorus moments, and another singer who plays Lili’s sister Elsa who sings chorus. And then there is the Svedova, an apparatchik.

What about the instrumental ensemble?

It’s relatively small. There are two saxophones, horn, trumpet, trombone and one percussionist. There’s amplified piano and one player doubling on electric guitar and bass guitar. And there’s the fixed media, the electronics.

Is there a political dimension to your approach to Mayakovsky? He did write a lot of propaganda and he was quite a determined Bolshevik in some respects but on the other hand he was the total opposite.

Well, he was never a member of the Party. He was known as the poet of the Revolution. He did poster art for them. The Party itself he despised.

But he went with it.

It’s like the Nuremberg Trials; just trying to survive.

Like Shostakovich?

They don’t issue too many pencils and pieces of paper in Siberia. You know how many people perished there? Both sides of my family had to deal with all that stuff, with Stalin and his enforced famine. It was dreadful.

There was an attempt to make a film about Mayakvosky’s life in 1973 in Russia but because it used footage from films [Fettered by Film, 1918, in which he co-stared with Lili, and The Lady and the Hooligan, in which he acted with her again and co-directed, 1918] showing him as a hooligan and a lovelorn loon it was refused funding. This was at the same time the State was building a museum to an idealised Mayakovsky, opposite the KGB building.

Yes, that’s what he played in his films. He was a big Charlie Chaplin fan.

So what does Mayakovsky represent? Is he like all of us, trapped in the very same contradictions, if less violently?

He symbolises everybody’s struggle with politics. We have our own troubles here. And the average person has more trouble than the rich. After the Revolution, the rich were very quickly supplanted by new people in power who got plenty of whatever they wanted. For artists, for intellectuals, people with their own minds, Mayakovsky’s a great symbol. Unfortunately he gave up early. It was 1930 and he was about 36. He could easily have lived on into the 1980s.

And maybe would have been a living inspiration to Yevtushenko and other Russian poets in the 60s who revived his spirit and the power of a dissenting public voice.

You just wonder what might have happened.

Sydney Chamber Opera & Carriageworks, Mayakovsky, composer Michael Smetanin, librettist Alison Croggon, conductor Jack Symonds, director Kat Henry, designer Hanna Sandgren, lighting Guy Harding, AV design Davros; Carriageworks, Sydney, 28, 30 July, 1 Aug 8pm, 2 Aug 2pm

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. web