Career optimism in tight times

Tina Kaufman

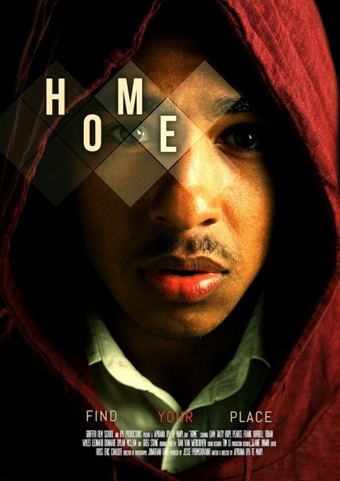

HOME, director writer Apirana Ipo Te Maipi, producer Jesse Phomsouvah, Griffith Film School. HOME won the Most Outstanding Script Award and Best Overall Film at the Griffith Private Craft Awards, 2013.

The local film industry was one of the big losers in this year’s federal budget, with government funding agency Screen Australia set to lose $38 million over the next four years. Screen Australia has since announced that most of the cuts will be made to documentary funding and ancillary programs, that its marketing department and state and industry programs section are to be replaced by a smaller business and audience department, that staff will be cut from 112 to 100 and support for screen resource organisations such as Sydney’s Metro Screen, Melbourne’s Open Channel and Adelaide’s Media Resource Centre will be phased out over the next 18 months.

CEO Graeme Mason argues that the changes will focus Screen Australia on development and funding of what he describes as “risk-taking projects that identify and build talent; intrinsically Australian stories that resonate with local audiences; and high-end ambitious projects that reflect Australia to the world.”

In June, Mason described the screen industry as contributing “$6.1 billion to the economy. It employs 41,000 people. When we come to town the spillover benefits and spillover effects are monumental—although this again is often forgotten by our detractors. Films and television programs are made with an eye to the commercial gains. It is, however, incredibly difficult to finance high-end television or a feature film and then see it through to completion on time and within budget, often in multiple locations, with a total cast and crew reaching up to 2,000 on big productions.”

“Producers,” he said, “have to be incredibly agile business people, managing a project from the chrysalis of an idea to a major-scale production, and the advertising and distribution to a wider audience over many years. To put this into perspective, on average it takes three-plus years and eight drafts to develop a project, and that’s before shooting begins. It is then another 12 to 18 months before the project hits a screen of any description.”

Globalisation & its benefits

So, given the severe budget cuts to an industry in which it is already very hard to make a film, are things looking gloomy for anyone whose tertiary education is aimed at a career in film? Surprisingly, no. There’s still a degree of optimism about the interesting and different career paths opening up for graduates. And what is contributing to this optimism? Primarily, it’s the increasing globalization of the industry, the many ways in which the role of the screen producer is widening and changing, and the ever-increasing opportunities offered by the explosion of digital production.

As Tom O’Regan, Professor of Cultural and Media Studies at the University of Queensland, and Anna Potter write in Media International Australia (No 149, Nov 2013), “Australian producers were once almost exclusively Australian companies accessing Australian funding schemes and courting international partners. They produced programs to imported and locally developed formats and created original feature and television drama production. Now they are just as likely to be transnational production companies utilising the global formats of parent companies and creating original Australian content, including for subsequent use as formats in other markets.”

This increasing affiliation of “independent Australian production companies with their global counterparts” is either through overseas companies establishing local operations, or the purchase of local production companies by international organisations. “These arrangements offer considerable advantages,” they add, “including access to global distribution and financing networks, specialised production knowledge and superior market intelligence.” And, of course, employment. With Australian film distribution, production, post-production and visual effects companies also being globalised, the expertise of local personnel should certainly lead to work in other areas of the new parent companies’ activities.

Speaking the languages

Universities and film schools are keeping up with this globalisation. They not only take international students, but as Lisa French, Deputy Dean, Media, School of Media & Communication at RMIT, explains, have overseas campuses as well. RMIT has campuses in Vietnam, Hong Kong and Barcelona, and students can undertake overseas internships or work on various projects with international partners. However she still sees as a problem the fact that Australian students don’t speak many languages. “RMIT does provide language courses, and in some courses it’s a requirement,” she says, adding, “it’s really important that this emphasis on language is increasing, as is the growing interest in Asia.”

Multi-skilling

Filmmaker and critic Peter Galvin, who has been teaching at the Sydney Film School since it opened in 2004, says the school attracts a number of international students who may have already worked in their local industries. “They come here to sharpen their skills and acquire a diploma; some then stay on, while others return. They come to our school for the same reason as our local students do—because they can make films here. Very few film schools or courses allow their students to make as many films as we do. Most of our students would work on about 15 film projects in a year, working on each other’s films—we encourage collaborations and partnerships. They may be working on two or three films at once, in different roles. They get a chance to diversify, to understand the different roles that go into making a film, and discover where their own interest lies. That’s not only a big output, it’s terrific experience.”

Alternative directions, new niches

While graduates with creative arts degrees in film and media might not have clear pathways to established careers, there are increasingly interesting and different directions in which they can find fulfilling occupations. Associate Professor, Media Arts and Production at UTS, Gillian Leahy says, “we’ve got graduates who are making music, directing drama, setting up sound companies. And they go to all sorts of places—working with film festivals, in classification, making digital displays for a museum, working in different areas of research.” She’s very pleased that while many of their graduates, “don’t end up anywhere near where they they thought they would, they still feel happy and fulfilled at the unusual direction they’ve taken. But then,” she adds, “there are those who really know where they want to go—and get there.”

As Stuart Cunningham Distinguished Professor of Media and Communications at QUT and Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, says, people who do creative work find all sorts of niches in advertising, marketing, creative services. Digital is ubiquitous, he says, “and there is a need for digital producers in mining, in health services, in training areas. Many graduates find stable employment working in creative roles for organisations outside the creative sector, or for firms that provide creative services such as design or media/communications to other businesses.”

And Lisa French explains: “we’re trying to produce graduates who are mobile, able to adapt, not afraid of moving into new technology. They’re more flexible, more creative, and can move into all sorts of industries. By the time they finish they have work they can show, but it’s not necessarily traditional work—it’s their potential, and if they are innovative and adventurous they’ll have lots of options.”

The new screen producers

The actual role of a screen producer is also changing; Stuart Cunningham believes that it now spreads across film, television, advertising, corporate video, and the burgeoning digital media sector. “In recent years, fundamental changes to distribution and consumption practices and technologies have brought about changes in both screen production practice and in the role of existing screen producers, while new and recent producers are learning and practicing their craft in a field that has already been transformed by digitisation and media convergence.” And he emphasises that it’s important to give filmmakers some business skills so they can establish start-up companies, or form partnerships. “These skills are much more necessary in this diversified world; government money is never going to be enough, so small business survival is important.

Producers are now being trained who can work in a wide range of entertainment areas, such as managing the entertainment on a cruise ship or creating digital content for a supermarket chain.” As Gillian Leahy says, “If you can produce a film, you can produce anything. If you master the details of producing, of budgets and schedules and time constraints, of getting your film finished and into the market, anything else would be easy!”

No glitz, no glamour

Producer Liz Watts, whose company Porchlight Films has produced Animal Kingdom, Lore and currently has The Rover in release, takes interns from UNSW, AFTRS, UTS and Metro Screen, and says she’s impressed not only with their enthusiasm and aptitude, but with their realistic attitude. “I do think they understand what a hard industry it is; they have no illusions about glitz or glamour.” She’s impressed with the way AFTRS and Metro Screen are establishing short courses that tap into skills gaps in the industry, in areas like SFX. “That provides more flexibility, and combines with more early interaction with the industry through internships that can only be positive.”

The group & time to think & create

One skill that is well worth acquiring is that of editing. Gillian Leahy says, “when you teach students to edit, the how and why, there are all sorts of jobs they can do. They can start editing promos, then move into making or producing promos for film, for television, for distribution and marketing. Their editing skill gets them started, and they can move into other areas from there. We give them a good grip of visual language, a sense of what works. And one of the great benefits seems to be that sense of a group effort, of working with others during their course, and then working with other graduates afterwards. We’re not just training them for the industry. We’re giving them time to think, to create—all the things that universities are supposed to allow them.”

New degree of optimism

AFTRS, Australia’s national screen arts and broadcast school, is certainly optimistic, with a new three-year Bachelor of Arts in Screen starting next year, designed to prepare Australia’s next generation of creative practitioners to be the leaders in their respective fields. The school, which has a process of adapting its courses to keep up with the needs of a changing industry, is looking to equip graduates for work in a platform agnostic world. But the course also recognises the importance of both narrative and tradition with its two core subjects, Story & Writing and The History of Film that will run for the full three years alongside elective specialist subjects. AFTRS CEO, Sandra Levy says the BA is all about critical thinking and creative engagement, and has been designed to ‘future-proof’ graduates for a changing and dynamic world post tertiary studies.

Documentary options

With the commissioning of and funding for documentaries already difficult, has the decision by Screen Australia to cut some of its documentary support made it a bleaker future for graduates specializing in documentary? Associate Professor (and documentary maker) Pat Laughren, from Brisbane’s Griffith Film School, says, “documentary makers, more than any others, are multi-tasking and flexible, and while it’s true that not much traditional documentary is being commissioned, there is an enormous amount of factual programming being made. And there is still corporate and industrial production, too; it may be shorter, and it may be streamed, but it will never go away. So those with documentary as their real ambition will still be able to find interesting and related work, even as the means of production and distribution change and evolve. And that’s just as well, because there are always a few students who really get the documentary bug!”

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. 24,29