Taking a hard look at the self

John Bailey: Melbourne – Kimmings & Grayburn, Hardgrave, Pratt

Tim Grayburn, Bryony Kimmings, Fake it ‘til you Make it, Theatreworks

photo Richard Davenport

Tim Grayburn, Bryony Kimmings, Fake it ‘til you Make it, Theatreworks

Much ink has been spilled lamenting the rise of the memoir in contemporary publishing, and while it’s debatable whether this turn reflects a culture of narcissism that interprets all experience by turning inwards, it seems without doubt most examples subscribe to a rather conservative notion of the self. The nature of identity and the individual are rarely problematised by writing that reproduces a particular narrow mode of realism and whose only formal playfulness might at best be some concession to the fallibility of memory. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been so surprised, then, when three recent theatre productions in Melbourne all turned out to possess elements of autobiography; however, it was thoroughly heartening to see that each took a rigorous and critical stance towards the performance of the self.

Fake It ‘Til you Make It

Bryony Kimmings and Tim Grayburn’s Fake It ‘Til You Make It might be the most naïve of these on the surface, but that simplicity has a function that is subtler than it appears. The work is a collaboration between performer Kimmings and her real life partner Grayburn, who has never appeared on a stage before. It takes as its subject his long-term experiences with depression and anxiety and Kimmings’ discovery of this well into their relationship. Structured around a series of discussions the pair recorded in their living room, it is composed of vignettes that spin off these conversations and explore the signs and symptoms of mental illness, its stigmatisation in public discourse and the models of masculinity that encourage a young man such as Grayburn to keep secret such a debilitating illness. The sequences incorporate dance, song, shadow-play and comedy in routines that are sometimes accomplished and sometimes lovably awkward; Grayburn spends almost the duration in a succession of headpieces sharply designed to shield the gaze of the audience from his, again reminding us of his nervous status as an artist.

There’s a contradiction at the heart of the work: performing a particular role of masculinity that denies vulnerability—the ‘faking it’ of the title—is precisely the problem at stake, and so producing a performance that addresses such a problem might only compound things. In order not to fake it, Kimmings and Grayburn must offer some alternative that can claim some authenticity, but what would that look like?

The duo make clear early on that this is foremost a love story, and Fake It is certainly not a comprehensive investigation of mental illness. It’s a portrait of a relationship, but it also becomes a part of that relationship, and through this the work manages to avoid that binary of artifice versus artlessness which a work about a ‘real’ issue might find itself in. The live-ness of Fake It is where we see the clear-eyed affection the two performers hold for one another, the fierceness of Kimmings’ need to wrestle social demons and Grayburn’s willingness to put himself in the dangerous spotlight so that others might find something of their own experience illuminated there.

It’s not as tightly constructed as some of Kimmings’ earlier work, and there’s a certain flatness to some scenes that is put in relief when more arresting moments arise—Grayburn’s thoughts of suicide when passing a favourite tree, or Kimmings’ panic when he lingers too long near an open window. But this contrast itself, whether intentional or not, has its own air of honesty. Any relationship moves through such phase shifts, and if Fake It doesn’t encompass the spectrum of male mental health it at least reminds us of the third voice that can be produced when two perform in harmony.

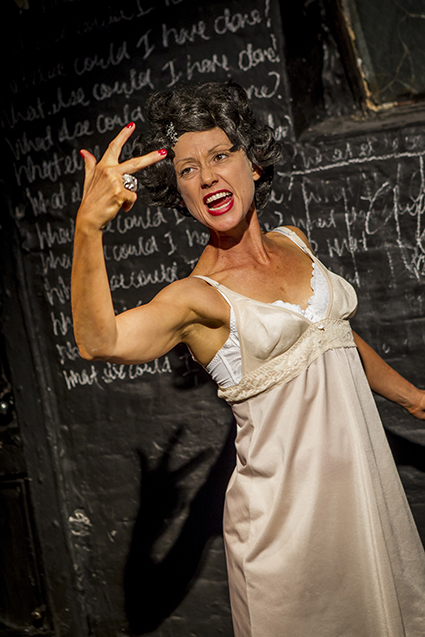

Suzie Hardgrave, Elizabeth Taylor is my Mother

photo Sav Schulman

Suzie Hardgrave, Elizabeth Taylor is my Mother

Elizabeth Taylor is my Mother

Suzie Hardgrave’s Elizabeth Taylor is my Mother approaches lived experience from more oblique angles. This solo work has been developed as part of Hardgrave’s Masters degree on authenticity in acting, but authenticity is not synonymous with sincerity. It’s a playful and ironic piece that interweaves fantasy and reality to such a fine degree that neither is really distinguishable; in her notes, Hardgrave describes research into psycho-physical theatre practices as they relate to “the personal and the ‘pretend’,” and the way that the self is produced through a mediation of these is where the production proves most compelling.

Hardgrave plays Cleopatra Velvet Rosemond Taylor-Burton, a figure who has clearly threaded together an elaborate private mythos in which Elizabeth Taylor gave her up for adoption in 1974, leaving her in the arms of an addict mother and abusive father. Hardgrave’s own experiences with adoption have played some part in the work’s formation, but are never given the position of privilege typically accorded the real. The narrating voice here is forever shifting register, from compulsive wit to a terrified reliving of trauma to sardonic speculation on what any of this really reveals. This isn’t a mystery of identity—’who is really speaking?’—so much as a rumination on the different scripts we use to write the self.

The Blueform

James Pratt’s The Blueform is an even denser layering of different modes of signification. Its ostensible story is familiar enough—a hapless schlub works in a Kafkaesque office from which there is no escape until he accidentally comes into possession of a blue form that can allow him access to prohibited areas, a glimpse into the dark machinations behind the totalitarian bureaucracy and, perhaps, even a window into another reality.

All of this could be just another rerun of the Orwellian dystopia that has played out in fiction ad nauseam, but Pratt’s facility as a comic and physical performer consistently undercuts the narrative to remind his audience of the blatant silliness of his premise. He’s an accomplished mime but there are sequences here that verge on meta-mime as characters undo one another’s actions by pointing out their artificiality. Pratt engages audience members directly and discusses how the show could proceed differently, and even brings the lights up for a false interval.

Somewhere in here, however, snatches of something that may be autobiographical emerge—moments in which a boy urged to try impro wins laughs from his schoolmates, or stages The Mikado with a young friend. These recollections are made misty by the surrounding frame of self-reflexivity, equally unreal but carrying with them the weight of a melancholy only time and age can bestow. Where Pratt’s hilariously unpredictable stagecraft works in opposition to the apparent confines his central character is supposed to be stifled by, the real tyranny might turn out to be the way that all life, all experience, sooner or later takes on the immateriality of fiction.

Fake It ‘Til You Make It, Bryony Kimmings, Tim Grayburn, director Bryony Kimmings, Theatre Works, 18 March–5 April; Elizabeth Taylor is my Mother, writer, director, performer Suzie Hardgrave, La Mama Theatre, March 18-29; The Blueform, writer, director, performer James Pratt, La Mama Theatre, Melbourne, 19-29 March

RealTime issue #126 April-May 2015 pg. 36