On the line between earth and sky

Kirsten Krauth: Castlemaine State Festival

Loomusica, Castlemaine State Festival

photo Pen Taylor

Loomusica, Castlemaine State Festival

Held every two years, and celebrating 40 years and 20 festivals in 2015, the Castlemaine State Festival is a vibrant cultural event that takes over the small goldmining-era town in regional Victoria. Many musicians, artists, writers and theatre-makers live in town, and this year almost 200 of them featured prominently in the program, inhabiting 20 newly commissioned works along with performers from Cuba, Cambodia and South Korea. A new festival hub was set up in the previously abandoned Castlemaine Woollen Mill bringing the sense of a central meeting-place (and, crucially, bar) missing from the last festival.

In Plan

graphics David Lancashire

In Plan

Michelle Heaven, In Plan

[SPOILER ALERT: IN PLAN WILL DOUBTLESS REAPPEAR IN COMING YEARS. BYPASS THIS REVIEW IF YOU WISH. EDS] After the first day of performances, people are fighting for tickets to Michelle Heaven’s In Plan; the moment I walk out, I buy another ticket. It’s a tricky show to write about because the best thing about it is not knowing what’s coming. But I’ll have to lead you in. As you walk into the dark, you’re given a numbered ticket while you put your shoes under a chair. The number correlates to one of a spiral of numbers up to 20 surrounding a large dark and curtained structure. You lie down and already the audience is getting nervous—My feet stink! I’m wearing a short skirt!—and put your head under the dark curtain, looking up. All our heads are gathered together in the round. It is quiet and meditative. A person next to me says, “If nothing else happens now, I’ll be happy.”As Bill McDonald’s soundscape shakes us, the performers (Heaven, Xanthe Beesley, Caroline Meaden) appear suspended above. I look for the cables, the ties holding them there, but there’s nothing. I’m afraid for them and us and wait for the fall. It’s like watching through a telescope, then kaleidoscope as bodies shift and distort in the small space. Silent, flickering, feet and hands. I feel literally suspended in disbelief. Then the plot thickens: a woman and man in love are tunnelling away from East German soldiers with jittery hands and elongated legs. The dancers’ bodies appear magnetised to the floor above—or is it below? They do not hang, and various floors slide over and between them, slippery spaces of silk (they’re building a parachute to escape) and then we’re in the sky, a naked woman revolving slowly through cloud, like a clock about to stop, falling or rising through the sky; it’s hard to tell. The sound rumbles through the tunnel and it’s as if we are both above and beneath ground at the same time. It’s exquisite to watch, the narrative clear and propelling, and it’s only when I sit up at the end that I realise I am dizzy, because I’ve held my breath for 20 minutes, entranced. It’s a show that I’ll keep with me as a precious object, a dreamscape (design Ben Cobham bluebottle; graphics David Lancashire) perfectly brought to life.

Jack Charles, Going Through

Aboriginal actor and elder Jack Charles, instrumental in setting up Nindetahana, our first Indigenous theatre group in 1971 with Bob Maza, was once imprisoned in Castlemaine Gaol. Local playwright John Romeril brings him back to town with Going Through, a play set and performed in the prisoners’ exercise yard. Its archway door opens to let the characters escape the prison, the wind blowing drought dust into our faces, and the icy drops of a storm fast approaching. The play starts as a two-hander, ex-cons on the run, freewheeling and farcical. But from the beginning, there’s no sense of the jail we’re standing in, or Charles’ place within it, as he struggles with the twists and turns of the play’s language. The tone of the performance is uneven too. While the sun setting on Lisa Maza singing opens the night sky as we look up beyond the walls, halfway through the performance she starts narrating in third person, a shift that seems forced and deadens the action, bringing us back to ground. Local actors James Benedict and Sue Ingleton ham it up (and there’s much laughter to be had from insider knowledge: James’ character works on the railways, while James himself once served coffee at Castlemaine railway station) but there’s a sense that the play lacks the contemporary sensibility it needs for this kind of festival.

At one point, when video imagery on the prison wall whisks us down a freeway (evoking the long-distance road trips we experienced as kids), the characters sit in a car and Ingleton mimes driving, curiously Play School, but we already know we’re travelling. There is a courageous moment, though, as Charles delivers a eulogy for his male lover at a funeral, delivered via video link on the wall. While I’m uncertain as to why the moment is not conveyed in person in front of us, it’s the most eloquent of the writing and performance, as Charles talks of his despair and love and relays an Aboriginal story of the first break of dawn, how the world was originally darkness and the magpies poked holes to let in the light—a moment that is truly transcendent.

Kekkai, Castlemaine State Festival

photo Pia Johnson

Kekkai, Castlemaine State Festival

Kekkai: Beyond Fixed Boundaries

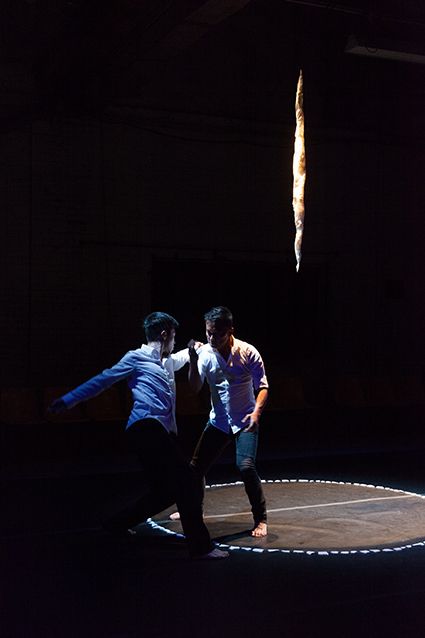

Kekkai: Beyond Fixed Boundaries is also about going through: defining barriers or forcefields, the line between dream and reality, between sky and earth. The collaboration between Nottle Theatre (South Korea), Tony Yap Company (Australia) and audio artists Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey pushes the audience to consider the quiet spaces and what divides them, what shuts us in and out. Four performers—Yap, Soyoung Lim, Euna Lee, Junghwi Park—dip their hands into a cylinder of blue, a ritual of washing, cleansing, longing. Korean words—low, urgent, disturbed—erupt from them. There’s the occasional English—“Where do your memories come from?”—but we are unsure if it’s direct translation. Strings hang suspended (woven into the frame of the Woollen Mills space), balancing the bodies of the dancers as they play with tension—marital, familial and sexual always poised. Tony Yap takes tiny steps in a lingering circle around a live piano wire that vibrates as he moves (linking with an art installation Loomusica nearby, a weaving of string and wool and suspended objects that plays sounds and creates music as you pull on them).

While at first the Korean women seem inert and passive, lounging around, they gather strength in small steps, until one races around the outskirts of the circle, feverishly, as if she can’t possibly go faster, desperate before she collapses (in Japan, kekkai stones often guard Buddhist temples, advising women not enter). Centre-stage is a circle lined by fragments of rock which, in a dramatic eclipse, Tony Yap smashes, kicking the circle line to the edges of the floor. Later, he completely covers a woman’s body with his, lying on top of her as if in mirror image, echoing the bodies of the lovers in In Plan.

Klare Lanson, #wanderingcloud

In the same room, days later, Klare Lanson’s #wanderingcloud takes on its next incarnation (see review, RT118), helped by a new space that focuses the project onto surround-screens and the isobars on the floor that Lanson tiptoe-traces as they curve around her poetry. The local audience, knowing all too well the power of floods and fire, have been creators too, with Lanson conducting trickle-down interviews, working from person to person, moving through Newstead, Carisbrook, Campbells Creek and Guildford, recording narratives and mapping disaster zones—and in the performance guitarist Neil Boyack, soprano Andree Couzens and performance artist Kathrin Ward also provide local presence. As Lanson does her final rehearsal, Brisbane-based Clocked Out percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson pours rice into cups, calling for calm and contemplation before the increasingly rare rain on the corrugated iron roof above drowns out the effect.

Wearing her “Don’t Talk To Me About the Weather” badge and floodline skirt, Lanson looks to the heavens for support. Hers is a project that, with festival and crowd-funding, continues to push the limits of poetry and performance, making a space for new writing, a space that’s contracted almost to the point of non-existence (in a shift from 2013, there was no writers’ program at this year’s festival).

While the standard of visual arts and performance can be high, there is also a great sense of small-town community at the festival, most of the people in the area turning up for the opening night at Western Reserve and a series of stages in Victory Park offering the best of clowning, vaudeville, acrobatics and bad 80s dance (a local joke says that Castlemaine has the most clowns and PhDs per capita in Australia). If you look closely, there’s something Portlandia about Castlemania (that’s the Facebook group for locals) and the festival; its eccentricity and inter-cultural exchanges capture the freewheeling spirit, and occasional unease, of what it’s like to live in a country town that’s changing fast.

Castlemaine State Festival, Castlemaine, Victoria, director Martin Paten, 13–22 March

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 27