Likeness unlimited

Keith Gallasch: Sue Healey, On View, Live Portraits; Branch Nebula, Artwork

Nalina Wait, Martin del Amo, Raghav Handa, On View

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nalina Wait, Martin del Amo, Raghav Handa, On View

The commonest expression shared among the subjects of portraiture—in painting, photography and film—is in fact an absence of expression, a neutrality which allows artists and viewers to search for meaning in the gaze, the wrinkled brow, a downturned lip, a scar, the tilt of the head. How often do we prejudge before even hearing a word uttered by a new acquaintance or fall in love across a crowded room? The Archibald Prize, sports cards, the family photo album and the selfie all confirm our passion for reading faces. In much of classical ballet and modern dance the expressive body does the talking, while the face is silent.

In On View, a modular work that can be exhibited as installation, screen works or live multi-media performance, filmmaker and choreographer Sue Healey provokes fascinating questions about the nature of portraiture as well as its relationship with dance. The large-scale performative version feels in some respects open-ended, a series of overlapping portraits, in others as though making a statement, which might be read in the work’s overall structure.

Shona Erskine, On View

photo Heidrun Lohr

Shona Erskine, On View

A pre-show set of intriguing installations introduces us to the dancers in enigmatic poses and actions not clearly related to what follows, if certainly a prelude to the mutability we’re about to witness. Once inside the performing space we observe a series of ‘portraits’ in which each dancer appears live and on film shown on five suspended screens. Sometimes the association is literal, sometimes lateral, as is the order of appearance—perhaps first the image, then the performer, the latter emerging from the shadows as if coming into focus, performing idiosyncratically and eventually fading out. A dancer as image might dart, prance or stumble from screen to screen while asynchronously realising the same movement on the floor. A live feed from a camera wielded by one dancer multiplies a second into various selves including one screened on his own body—self on self.

Between the realising of these individual portraits the dancers form small groups or gather as a whole. Initially their movements are disparate, panicky and uncohesive as if not knowing ‘where to put themselves.’ As more portraits form and fade, the performers connect more confidently in tight geometrical patterns. Later they embrace in various configurations, as in the live camera portrait-making, and finally there’s a sense of ritual (a striking golden cape shared between dancers), transcendence and commonality underlined by a booming score replete with high choral voices. Perhaps On View adds up to nothing more than a reverential celebration of our being at once discrete individuals and members of an ideally harmonious species, and perhaps that’s more than enough.

What saves On View from overstatement is the specificity of its portraits, even where there is redundancy (the juxtaposition of similar movements live and onscreen is not always meaningful) and over-elaboration (our having to constantly choose which aspect of the portrait to take in).

Nalina Wait breaks the neutral expression rule with eye-to-eye seductiveness as she parades in long wig and high heels past the audience (like a performer from Pina Bausch’s Kontakthof daring a smile). Later she indulges in before-the-camera face-pulling. Unwigged and high-heels removed, she dances sinuously like the fish swimming in the film behind her. But a massive soundtrack crunching presages the disintegration of her self-possession into staccato stumbling across stage and screens, utter vulnerability revealed. So it is that each dancer appears in different personae, settings and sounds. On film Raghav Handa comfortably handles and rides a horse; on stage his Indian-influenced dance requires the same kind of low centre-of-gravity virtuosity. Martin Del Amo’s trademark ambulatory dance is likewise earthed, gaining new intensity with slow, tight turnings.

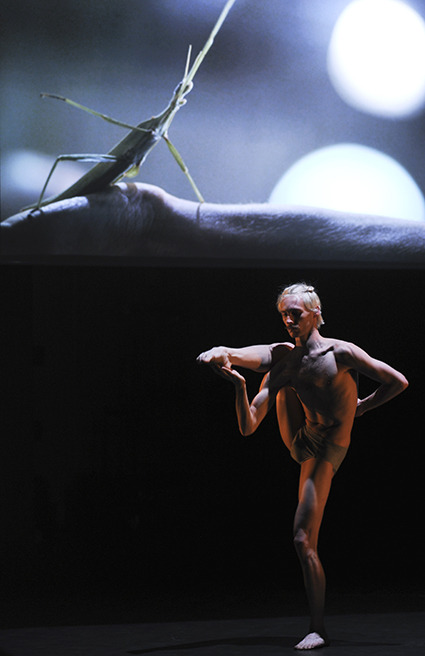

Benjamin Hancock, On View, photo Heidrun Löhr

Benjamin Hancock opts for relative stillness, his body unfolding slowly with exquisite, angular yogic poise, seen in parallel with a praying mantis on film balanced on the performer’s skin. This dancer’s capacity for transformation here and elsewhere in On View is remarkable. Nature appears again with Del Amo seated on a stone plinth in a cemetery, an owl perched next to him and another bird swooping down aggressively; it was one of those ‘did I see that?’ moments which added to the work’s escalating sense of strangeness. Shona Erskine dances with her usual supple refinement becoming amusingly erotic when she sensually embraces a fox fur in a series of poses.

As with any portraiture the connection between subject and image is tenuously suggestive. Yes, for example, Handa does ride horses; no, Erskine is not a fox fur fetishist (the prop prompted interest when found in the development phase of the work; so we were told in a Q&A). Healey seemed to have been interested in finding places and things with which each dancer might feel some affinity, whether deep or circumstantial, and which might be revealing. Of all the portraits, the one of Nalina Wait seemed the most literally and effectively suggestive; but was it ‘one’ portrait or two, or merely two games? When a camera multiplies images of Del Amo and projects them onto him, are we seeing contemporary narcissism laid bare or a reflective personality?

Benjamin Hancock, On View

photo Heidrun Lohr

Benjamin Hancock, On View

Healey’s fine 2013 feature documentary Virtuosi, with its accounts of eight leading New Zealand dance artists in words and movement, revealed the filmmaker’s precise grasp of the portraiture idiom. On View is a very different take on it—a busy, impressionistic live work mixed with expressive cinematography (Judd Overton) and rich in detail with which we aggregate imagined personalities for its impressive performers. It challenges its audience to muse on the meanings, values, strengths and limits of portraiture while enjoying idiosyncratic performances that collectively perhaps add up to something quite singular.

Branch Nebula, Artwork

On a very large screen in Carriageworks’ vast principal performance space, we see a row of unidentified, seated people receiving instructions from a man with a clipboard, including a reminder to fill out Taxation Office forms to ensure their payment for the work they are about to do. In what follows, these people are casual workers. In the spirit of the production, my work is to list what they did: one labours with bucket and mop, one with a tea trolley and one bashes a cushion with a cricket bat. The tedium of these tasks is underlined by extended duration, the amplified rattle of tea cups and the mopper’s brief escape into dance. An older man simply stands before us as one of the camera crew circles him close-up such that we read the face in intense detail projected onscreen. In the far distance a girl bounces a ball off a wall. Someone wheels a clothes trolley. A chair is thrown. A camera is aimed at the audience which is puzzled, bemused, giggling, indifferent. The ‘workers’ walk towards the audience blank-faced. The tea trolley man slowly devours a whole packet of potato crisps. The workers cover their heads with blankets. A flood of table tennis balls is released. We hear a call centre conversation and from time to time catch repeated speech fragments: “going to the beach … the very last day of his life…we all deserve respect …we’re all human…a portion of soul.” There’s dancing and at the end some smiling. Members of the audience join the workers, sharing in the labour of collecting the table tennis balls.

Extreme lighting states, a heavily dramatic sound score, simultaneous performances, live video feed and the venue’s extreme depth of field lend the actions a strangeness that heightens the banality of the unskilled labour portrayed by these non-actors, who, aptly, are minimally instructed, but not rehearsed, when they arrive shortly before the show. At the same time, as a work made with unskilled performers, Artwork is one of many to be found in live art and the likes of post’s Oedipus Schmoedipus. But Artwork is the sparest and most basic of these, a kind of instant theatre—here are all the effects, just add people. As far as we know, Artwork is not about these people: there’s little information about the ‘auditioning’ process. Are some the exploited workers they represent? All they can do is perform like the exploited, for the most part with a minimum of visible confidence. The company cannot claim that the performers are empowered, but if they are, we’ll never know. Next to Branch Nebula’s conceptually stronger, provocative creations of many years, Artwork is a slender conceit that awaits embodiment.

Performance Space: On View, Live Portraits, film Sue Healey, choreographer Sue Healey in collaboration with performers Martin del Amo, Shona Erskine, Benjamin Hancock, Raghav Handa, Nalina Wait, director of photography Judd Overton, music Darrin Verhagen, Justin Ashworth, lighting Karen Norris; Carriageworks, 17-25 July; Carriageworks: Branch Nebula, Artwork, collaborating artists Sean Bacon, Phil Downing, Teik Kim Pok, Matt Prest, Lee Wilson, Mirabelle Wouters, dramaturg John Baylis; Carriageworks, Sydney. 5-8 Aug

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. 10