Audiovision: Domestic violence in the white cube

Philip Brophy: Cassandra Tytler’s I’m Sorry

I’m Sorry, Cassandra Tytler,

I have never understood the hang-ups people have about white cubes. The more you try to remake and remodel its void—let alone vanquish it—the more you prove its power. Surely the white cube has become a most promiscuous public space wherein anything is acceptable and all is possible.

How many times have you walked into a gallery or museum whose white cube zone has been deterritorialised, deconstructed, demolished? Walls are punctured, flooring is covered, air ducts are exposed. Or, frames, partitions, boxes, shelving and rooms are constructed as metaphorical refugee encampments or sites of resistant occupancy. For many, this enlivens contemporary art’s critique of architectural politics—a shallow view, considering the cultural context within which galleries and museums ape lifestyle trends of customisation and empowerment, while IKEA and Bunnings encourage you to transform your domestic space into a personalised white cube. The Block vs The Sydney Biennale. Grand Designs vs The Turner Prize. Is there really a difference?

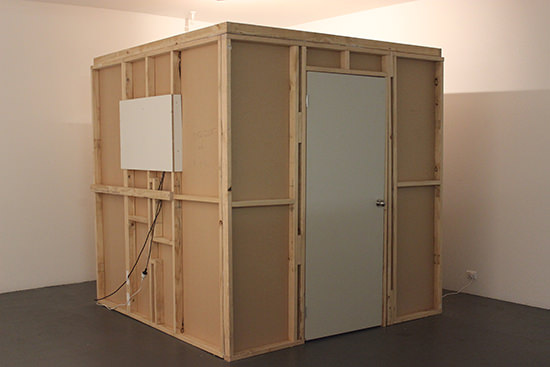

In an exhibition featuring Cassandra Tytler’s video installation, I’m Sorry (2016), this familiar scenography appears once more. Another artist-run space with concrete floor, white walls, track lighting. Another box-room built within the space, sitting like a defiant edifice, reclaiming the space to make a personalised art statement. That’s how it looks from the outside, what with its ugly exposed ‘interior’ wall studs and framing, the kind that Institutional Critique loves to ‘expose’ within a gallery or museum.

The difference with I’m Sorry, though, lies in its awareness not only of the pitfalls of even bothering to critique ‘art’ (what is it with artists doing it all the time?), but of the precise reasons for making a shitty Bunnings box construction inside a gallery space. This work is not about where you are in the gallery: it’s about where this box comes from. Like a random container drop, it imports a plain suburban room into the gallery. You enter through a Bunnings door to find yourself inside a scaled-down living room of sorts—low ceiling, white walls, faux-Afghan carpet, a small table with flowers in a vase. Two ‘windows’ (actually flat-screen monitors) on the left and right walls are each positioned at chest height. It’s neither a house nor a home; it’s just a dumb space, a petite hell for its inhabitants. This room is a domestic void, placed within the void of the white cube. As a visitor to the gallery where art and reality pathologically mirror each other, one is now trapped inside this portal to the domestic world where shit happens.

All public galleries these days run boutique vodka tastings, kids’ craft workshops, comedian talks, themed cooking classes and senior citizens’ walk-throughs—for even the most rabidly, politically oriented contemporary art exhibitions. Like the medieval ‘city square’ notion of congregational activities which contemporary urban planners flaunt in all global cities desperate to be socially relevant while hysterically building pseudo-inner-city lifestyle developments, public galleries domesticate their space as an antidote to the solipsistic core which silently throbs in so-called socially motivated art. Amid this neurotic, curated reassurance that art and society miraculously mandate each other’s co-dependency, how does an artist today even frame the outside world, let alone provide commentary from an artistic perspective?

I’m Sorry, Cassandra Tytler,

The ‘window’ flat screens of I’m Sorry feature Tytler dressed and made-up as a man. It’s ineffectual and unconvincing: elfin short hair, some fake stubble, no lipstick or eye-liner—a drag king shopping at IKEA. He first appears on the right screen, banging on the glass, barking again and again and again, “I’m sorry.” We know the story: he is the lover/partner/husband singing a pathetic refrain of repentance which fuels the cyclical nature of domestic violence. It’s never a one-off or last time; only ever a loop, a return, a repeat. He exits the window on the right and appears on the window on the left. And starts up again with his banging and pleading: insistent, dogged, irritated by having to state his case. He gets angrier with each mantric utterance. He moves to the right window again. Then the left. Then the right. Then the left. By now, he has dissolved into a breathless, indignant cartoon of frustration. The remorse faked earlier has been retracted; he’s now insulted by having to even acknowledge wrong or be engaged in any ridiculous reconciliation. The apologetic has now transformed into the apoplectic.

It’s a queasy performance. Firstly, Tytler moves from drama school acting into eventual full-blown melodramatic mime. Unlike most contemporary video art which now employs the Cate Blanchetts of the world to sycophantically infuse its art with cinematic performativity, Tytler’s performance in I’m Sorry mirrors the inauthentic posturing of the repeat offender inured to both clinical strategies by therapists and passive-aggressive manipulation by do-gooders.

Secondly, I’m caught remembering how embarrassing it is when you see how pathetically people act when cornered, exposed, caught, tried. No-one hangs their heads in shame these days. Everyone feels they have the right to fuck up how they choose. The socio-cultural persistence of domestic violence is bound to send subliminal messages to the ethically-skewed mindsets of its perpetrators, who feel violated by the humiliating exposure of their private domestic hell. Like Tytler’s ‘everyman,’ the abuser feels more wronged than wrong. Standing inside the crappy Bunnings room built by the artist, I thought of countless dads fixing up their houses, smoothing over their problems, patching up their relationships, plumbing their anger, building up their frustration, hammering away in self-loathing. The proliferation of TV reality shows predicated on constructing dream homes built by hunky metrosexual elves accrues an icky reactionary prescience under these conditions. The flaccid melt-down performance of I’m Sorry amplifies these connections: dad is just a dick.

And then there’s that sound heard throughout the video. A non-stop banging on the window, like the Big Bad Wolf pleading to be let in. It’s the distinctive sound of a hollow boxy boom, frail in force yet ungainly, articulated by upper-bass-range thudding. It’s the sound of someone gagged and trapped in a box begging to be let out. Or the sound of yet another temp employee with a clip-board wandering through the suburbs trying to get you to change from one branded service to another, for no good reason other than flat-lined marketplace competition. Or the sound of a million tradesmen fabricating a million boxes for designer shanty towns, bashing away with tools bought at Bunnings. Or the sound of your neighbours banging on your wall. Or you on theirs. It’s the sound of the outside world, never leaving you alone, even after you have modelled your petty square meterage into that IKEA image of retro-Euro-Modernism aping Bauhaus-revivalist contemporary art museum café design. Ironically, it’s also the sound of pseudo-cinematic video art projections inside black boxes inside white cubes (or disused industrial sites à la mode) for biennales around the world. A psycho-acoustics demonstrating the deafness of video artists fawning over their hi-res imagery but deaf to anything sonic, aural or vocal. Here, it’s the sound of the outside world banging on the windows of art. With its consistent performativity and tonality, I’m Sorry unapologetically has nothing to say about art, galleries, white cubes and their glorified relevance to the outside world. Apology gratefully accepted.

–

Cassandra Tytler, exhibition, Tock Tock, work I’m Sorry (2016), video installation, Gallery One Trocadero Art Space, Footscray, Melbourne, 18 May-4 June

Cassandra Tytler works with single channel video, performance and installation, focusing “on processes of embodiment of the gallery space and how movement, vision and audio can create an intersubjective feedback between viewer and artwork… [with] an ongoing examination of masquerade and mimicry in video-based practice.” She has presented live video performances and exhibited works in Australia, Paris, Turku (Finland) and Miami, has a Masters degree (RMIT University, 2003) and is currently a PhD candidate at Monash University, Melbourne.

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016