Imagination and incarceration

Elyssia Bugg: Squidsolo, RIMA

Julie Vulcan, RIMA

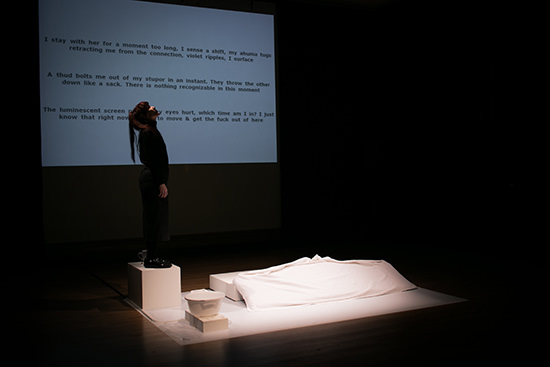

Julie Vulcan is kneeling on a white rectangle, counting the indentations in a white blanket draped across a structure that constitutes a narrow white bed. It’s barely half an hour into her 23-hour stint in this two by three-metre wall-less ‘cell’ but Vulcan already seems restless, and perhaps she must be, not only for her sanity, but for the work to function. A computer program, or “virtual room,” is monitoring the state of the cell and its inhabitant through qualities such as movement, heat, light and sound. In this moment, the system is filling the space with a quiet static, a swooshing reminiscent of sliding doors.

Though the work is focused on the experience of solitary confinement, Vulcan is not entirely alone in undertaking the durational performance that is RIMA. In a corner of the room, a short distance from the confines of her rectangle, Vulcan’s collaborator Ashley Scott mixes the soundscape. On the back wall a series of short correspondences are projected in groups of three, fading, reappearing and being replaced as they’re triggered by Vulcan’s movements. The text, simultaneously posted on Twitter, is a nonlinear series of dual dispatches from a dystopian future, or perhaps futures. One persona details an exploratory mission through science-fiction techno-jargon, exemplified in lines like, “In CN0 we wait for the initiation procedures. We wait for the signal from Umbraz. I am in awe.” In contrast, another persona narrates the harrowing physical and emotional struggle of being held captive in a state of solitary confinement, expressing growing despair in phrases such as, “Here is human desolation. Here is human desecration.”

Watching Vulcan pace around her cell is at times uncomfortably voyeuristic, but the problem RIMA’s audience faces is not whether or not they should avert their gaze. Instead the difficulty exists in locating a sizable point of entry amid the cross-platform, cross-medium, inter-textual content. As a work that can be watched in person or via a live stream, as well as sought out on Twitter and contextualised via a series of accompanying essays, RIMA makes gaining a holistic sense of engagement a challenge. However, it is apt, maybe even necessary, for a work about incarceration to refuse to provide its audience with an easy way in, or out.

In a week where images of abuse within Australia’s juvenile detention system have filled newsfeeds, a work such as this could become tethered to, or oversimplified by broad political debate. Yet RIMA’s concern is with the internal, with how we can, or must, narrow in on particular ideas, feelings, gestures, in order to make sense of the present and our shared humanity. Checking in on the live feed, searching the Twitter dialogues for something recognisable, something representative of my understanding of the world, I felt the vastness of abstraction in the work, rather than the claustrophobia of confinement, become actively oppressive. Consequently, for all its ideological reach and technological dissemination, RIMA is asking its viewers to hone their gaze, focus their attention. It is, as Vulcan writes “a cry for vigilance” (the title of one of her essays is “A sliver of wood and a drop of blood: Keeping the lines open) in an age where constant updates and data streams can lead to overwhelming apathy.

Julie Vulcan, RIMA

In the piece’s accompanying notes, Vulcan includes an interview she conducted with paralegal and human rights activist Charandev Singh. Commenting on the emotional toll of incarceration Singh says, “All of the impacts of solitary confinement are intentional.” There is a parallel kind of intentionality in the performance of RIMA that seems jarring. Vulcan begins the performance standing, arms crossed, glaring at the ceiling. Later she clasps the white mug that has been set on a table for her and peers dramatically into it. These actions, in conjunction with the Twitter updates (composed pre-show and triggered by Vulcan’s movement), disrupt the reality of her present situation with a sense of the scripted. The actuality of her personal experience registers only durationally and in the minutiae of the computer’s environmental tweaking. Though exceedingly self-conscious, these theatrical elements serve to blur the lines between past, present and future, contributing to what Theron Schmidt, in his accompanying essay, “Living in augmented times,”calls “a form of augmented reality.”

After 23 hours, the piece ends as Julie Vulcan slowly stands and exits her cell, leaving the room still and silent. RIMA is a work fascinated with the way in which memory and imagination can be torturous, but also harnessed as survival mechanisms, as tools of comfort and hope. This idea is echoed in the Twitter correspondence: at one point the incarcerated character laments, “Sit with me please sit with me now. I try to conjure you from somewhere in the back of my memory. Try to bring you into focus.” It’s in the final image of absence that the audience may truly focus on the presence of moments past and potential futures; filling the space with a reality separate from that of the present, from the world outside. This is itself a kind of freedom.

–

Squidsolo, RIMA, performance, text, set design Julie Vulcan, music, web, computer programming Ashley Scott; Arts House, North Melbourne, 30-31 July

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016