Remarkable musics

Keith Gallasch: five concerts

1967: Music in the Key of Yes concert, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Prudence Upton

1967: Music in the Key of Yes concert, Sydney Festival 2017

Five concerts revealed the strength of the 2017 Sydney Festival programming of unusual concepts, forms and instruments. This was music-making of high order for welcoming audiences.

1967: Music in the Key of Yes

In the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall, Yirrmal Marika opened and closed this superb concert (which will be repeated at the Adelaide Festival) with a fine sense of ceremony. His remarkable vocal skills (performing largely in language), didjeridu playing and dance (birdlike to Emily Warrumara’s account of the Beatles’ “Blackbird”) evoked a vast cultural history in dialogue with powerful popular songs in an event focused on celebrating a crucial political event, the 1967 Referendum that recognised Aboriginal peoples as Australian citizens.

On two large upstage screens, archival film deftly unfolded an impressionistic narrative from across the 20th century, featuring images of traditional Aboriginal pride, assimilation, destitution, protest, and the speeches (notably from Faith Bandler) and polling booths of 1967. Brief interviews with the public at that time revealed support, condescension, prejudice and hostility. Oddly missing from the footage were images of the beauty of country so fundamental to Aboriginal life.

The singers—Yirrmal Marika, Emily Warrumara, Leah Flannagan, Dan Sultan, Adalita, Radical Son, Thelma Plum, Alice Sky, Ursula Yovich—and a wonderful supporting ensemble led by Neil Murray drew on a wealth of Australian songs. “My Island Home,” Archie Roach’s “Took the Children Away,” Warumpi Band’s “Blackfella/Whitefella” and Yothu Yindi’s “Treaty” were heard alongside Goanna’s “Solid Rock,” Midnight Oil’s “Dead Heart” and American classics such as Sam Cooke’s “Change is Gonna Come” (a powerful rendition from Radical Son), Nina Simone’s “Feelin’ Good” (Thelma Plum in a beautifully restrained account) and Patti Smith’s “People Have the Power.” Among other pleasures was Dan Sultan’s affecting “The Drover,” about Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari, the stockman who became a leading land rights activist.

With its songs passionately performed, subtly arranged and juxtaposed with historical film and an intriguing projected text by novelist Alexis Wright, 1967: Music in the Key of Yes generated an embracing sense of community between singers and audience. A rousing ensemble encore rendition of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends” was followed by a sense of return to ceremony in a gentle transition from “Blackbird” into Yirrmal Marika’s performance of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s “Wukun,” a song about storm clouds (Wuku) which are images of the songwriter’s mother’s people, the Gälpu.

Ellen Fullman, Theresa Wong, Long String Instrument, Sydney Festival 2017

photo by Kjeldo

Ellen Fullman, Theresa Wong, Long String Instrument, Sydney Festival 2017

Ellen Fullman Long String Instrument

Eyes closed, ears wide open, I’m swathed in the complex hum and buzz of Ellen Fullman’s 25-metre-long string instrument which the artist plays as she walks the great length of its resonating wires, holding them pinched between her fingers. The aural halo conjures string orchestras, sitars and electronic droning (the device is acoustic but its resonating boxes are miked), music rendered more complex by Theresa Wong’s cello layering of slow, deep riffing and digitally treated high carolling. Eyes open, it’s performance art: the slightly built Furman first moves slowly backwards for much of the length of her instrument, close enough for me to hear the soft click of her white-soled black sneakers, then all the way forwards and then, in shorter forays, in both directions, pausing only to apply rosin to her fingers or set a small motorised wheel spinning to generate a drone passage. Definitely a show for those into sheer reverie and the musical unusual. I ached for a post-show demonstration of the instrument’s capacities. Which, in a way, was what Chris Abrahams offered in the show’s opener on the Town Hall’s magnificent organ, unleashing its highest and lowest notes—the latter unearthing a rumbling, mechanical beast—and, in between, playing passages of delicately considered counterpointing and soaring organ romance.

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Jamie Williams

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Sydney Festival 2017

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires

After experiencing Montreal composer Gabriel Dharmoo’s Anthropologies Imaginaires, I was buzzing and twitching with a profound sense of the pre-verbal, pre-instrumental music of tribal peoples as played by this virtuosic artist via complex vocalisations, physical self-manipulation and movement, subtle and rough.

Having just enjoyed the Denis Villeneuve film The Arrival, in which a linguist (Amy Adams) attempts to communicate with giant heptapod aliens, and reading Ross Gibson’s 26 Views of a Starburst World (UWA Press, 2012) about the 1790s encounter between English surveyor William Dawes and 14-year-old Patyegarang (read in order to better appreciate the festival’s attention to local language), I attended Anthropologies Imaginaires eager to appreciate a composer’s account of ancient music-making across cultural and temporal barriers. I was in for a surprise.

What I encounter is a lean, dark-haired young man in black T-shirt and trousers who never speaks but performs a series of non-verbal utterances, tuneful and otherwise, each introduced by onscreen cultural experts who identify and comment on the tribes who made these proto-musics. The vocal elaboration and gesturing is convincing, commencing with a wordless prayer with wafting notes, clicks, falsetto and allied hand glides. As the performance proceeds, the cultures the artist evokes grow stranger, though the techniques—yodelling, overtone singing, vibrato-induced chest thumping and rasping growling make sense—but in this case all from one tribe? Then there are screen cutaways to a making-of-documentary in which the ‘experts’—whose commentaries are beginning to sound weird—are revealed to be stage hands. A demonstration of the music of “Third-Sex Children,” delivered from a low, wide-legged stance and in long-note falsetto and mask-like face-making evokes Chinese opera but perhaps also ancient Indian dance in which one performer plays multiple roles.

“Weborgez,” is a 12-tone music culture in which music is literally presented as child’s play. Irony and parody have clearly entered the frame. An exorcism for “male sexual guilt” in another tribe is executed by vocalising into a bowl of water, drinking and expelling the liquid as if vomiting, violently wrenched from the stomach, and then self-flagellating after cleaning up the mess. The audience giggles. Any sense of reality has long exited. But even so, the “Aquatic Songs” sequence, with water kissed, puffed into, sucked and voiced with a pulsing falsetto, seems plausible.

We are gently cajoled into becoming a trance choir so that, as an onscreen specialist derisively puts it, the leader can “solo purely egotistically.” One tribe is condemned for its failure to drill and mine—the mumbling performer looks lost. In contrast, a “hit song” follows—jazzy, pop and “world,”—its culture celebrated for having survived via cultural absorption (akin, of course, to mining). Finally, the specialists are revealed for what they are: casual surmisers, ideologues, a Minister of Assimilation and a promoter of wine and golf tours. Our shared culpability in desecrating cultures we don’t understand has been deeply sounded in Anthropologies Imaginaires with the tools of musical expertise, deployed with wit, vocal grace and dextrous physical performance.

Einojuhani Rautavaara

photo Sakari Viika

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Rautavaara

Things that fly. Birds. Angels. Spirit. Mine did in the Sydney Festival’s Rautavaara concert, lifted by superb performances of the composer’s distinctive blending of impressionistic world-making and soaring neo-Romantic melodising. Einojuhani Rautavaara died on 27 July, 2016. This tribute event offered a scandalously rare opportunity to hear his work in an Australian concert hall, in this case one with an ideal acoustic, warm and responsive to the tiniest details in orchestration and the recording of the bracing calls of huge flocks of swans commencing migration from Finland’s north.

Cantus Arcticus, Concerto for Birds and Orchestra (1972) features birdcall taped near the Arctic Circle in marshland and bogs awash with birdlife. It opens with an entrancing, warbling flute duet (beautifully acquitted) which is then joined by woodwinds, together anticipating the arrival of the birds and a corresponding swelling cello-led melody. The subsequent shifting dynamic (sensitively captured by conductor Benjamin Northey) between orchestra, individual birds and flocks (the calls sometimes pitch-adjusted by Rautuvaara) achieves a glorious synthesis of avian and human music-making, above all in the work’s glorious third and final movement, the swan migration, transcending the fleeting suspicion that you’re listening to the score from a nature documentary. A trumpet soaring above the fullness of the score’s unsentimental sense of triumphant nature suggests the flock rising to leave while flute and woodwinds carroll indefatigably, as they did in the first movement, at one with the swans. Softly descending harp notes signal departure within seconds. Silence. Although heard many times on CD, this live performance breathed new life into my appreciation of Rautavaara’s sublime entwining of birdsong and the music we ‘sing’ through our instrumental prostheses.

The intensely dramatic 11-minute Isle of Bliss (1995) also evokes birds if not so literally, its inspiration Finnish dramatist Aleksis Kivi’s “Home of the Birds,” a poem seeking repose, possibly the calm of death. After opening forcefully with a rising sense of urgency—woodblocks rattling and flutes piping, bird-like—calm briefly ensues until recurrent deep string orchestral strummings introduce a return to the opening melody, now yearning and soaring. It is twice interpolated with ‘birdcalls,’ which towards the work’s end become incessant chatter beneath the emotional turbulence and then, on their own, dive into a sweet tumbling of notes and, wonderfully, a final lone, gliding two-note call, so distinctly birdlike. Northey and the orchestra have delivered us and the poet, with care and passion, to the Isle of Bliss.

With larger instrumental forces, Symphony No. 7 Angel of Light (1994) evokes the power and sense of transcendence associated with angels but also their role as intermediaries between god and humans. French horns and brass rise above full-bodied, sometimes keening, sometimes soaring strings in another of Rautavaara’s surging constructions—here underlined with strummed harp—and their descents into thoughtful, meandering reflection. Angels here are reassuring, the movement ending in calm. The second movement’s series of three powerful trumpet calls, from two slightly different pitched instruments—followed by brief bursts of fearsome percussion, conjures alarming angels, although their last fading appearance, undeniably bird-like (and wonderfully played), softens the angst. As does the dream-like third movement, a reverie ending with soft, repeated warblings behind the string and horn musings. The brass fanfare opening the final movement is followed by emphatic carrolling from woodwinds and strings—akin in the density of movement to Canticus Arcticus—underscoring soaring brass. In the ensuing softening, we see the trumpets muted but finally no less powerful in the work’s climax, simply more integrated, bringing human and angel together. Rautavaara didn’t aim to write a programmatic work, but the kinship of birds, angels and spirit were evident in the concert’s admirably selected three works and superbly conducted by Benjamin Northey with the balance of restraint and release necessary to realise Rautavaara’s vision.

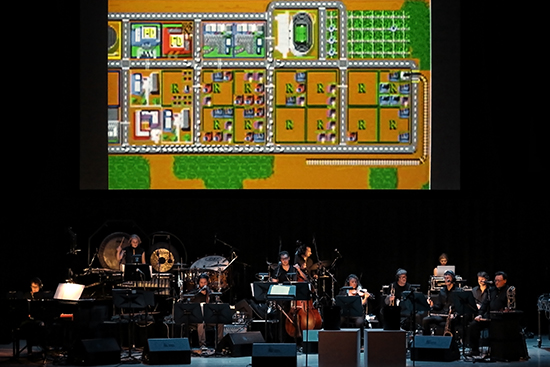

AAO with Nicole Lizée (top R), Sex, Lynch & Video Games, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Prudence Upton

AAO with Nicole Lizée (top R), Sex, Lynch & Video Games, Sydney Festival 2017

Nicole Lizée, Sex, Lynch and Video Games

Nicole Lizée with the Australian Art Orchestra, Sex, Lynch and Video Games was another festival highlight, an exciting and fruitful pairing of Canadians (Lizée, pianist Eve Egoyan and guitarist Steve Raegele) and Australians (AAO, led by Peter Knight).

Lizée ‘s David Lynch Etudes (she’s also tackled Hitchcock) are played by Egoyan to projected and radically edited clips from David Lynch films. The outcome is funny, alarming and aesthetically satisfying in the fusion of playing that yields rippling waves, dark intoning, astonishing stuttering and grand romantic pianism with revealing investigations of very short film moments. My favourite was of Naomi Watts as Betty in Mulholland Drive (2001) surprised by the sudden appearance of Laura Harring as Rita. Lizee cuts and repeatedly stutters the film so that it becomes an intense, sustained portrait of Betty saying “You came back” in quickfire states of happiness, shock, fear, suspicion and hatred as the piano shuffles darkly. Watts is perfect for such dissection and elaboration. As are Nicholas Cage and Laura Dern in Wild at Heart (1990) elsewhere. At one point, Egoyan leans to the side and plays slide guitar as well as piano as a guitar is played in Twin Peaks onscreen. Motifs emerge that appear in this and other excerpts in the program: images totally flaring or sparkling, a brush appearing and painting in, for example, tears, small photos of characters (and Lynch) placed on a tongue, and an obsessive preoccupation with seemingly incidental details like the window that the camera tilts towards and away from Watts. I’m not sure what they add up to but they lend the works an intriguing totality. What is impressive is not only the dynamic between live piano and edited visual imagery but the cut-up sound of the film made musical in itself and in tandem with the keyboard.

In B-Bit Urbex, Lizée, now upstage with the orchestra at her computer, plays with malfunctioning early computer games, with a keen focus on their “pixelated cities.” The simple, often stuttering images and freezes are aurally textured with complex music that has to responsively slow, compulsively repeat or hover. Band members clap in time, two trumpeters play into buckets of water, there’s a wild big band passage and some fine gentle guitar work, pitched against the image of a plodding game robot. The unpredictability of these old games yields rich musical rewards.

Gian Slater, Tristram Williams, Sex, Lynch & Video Games

photo Prudence Upton

Gian Slater, Tristram Williams, Sex, Lynch & Video Games

After a turntabalism improvisation between Lizée and Sydney’s Martin Ng, which, though fascinating in part, warranted more duration to be revealing, the concert concluded thrillingly with Karappo Orestutura (literally “empty orchestra”) in which a singer adjusts her performance to a malfunctioning karaoke machine (as played by the Australian Art Orchestra). Gian Slater, in superb voice, stays ‘in tune with’ the warped pitches, grinding glides and relentless repeats, maintaining, as Lizée requests, “composure.” Things begin well enough, songs complemented by old footage of couples kissing, fighting, crying, hugging and images of fire. Then a screen explosion anticipates a world about to go wonky, which it does with Devo breaking up on screen and the singer seamlessly executing fractured vocals for “Whip It.” Unexpected images pop-up: the joint-sharing scene from Easy Rider, the dead mother in Psycho, as if the imagined machine has locked onto some other platform. The climax is spectacular: Diana Ross and Lionel Richie onscreen in aged video gazing lovingly at each other, microphones in hand for “Endless Love,” their voices finely realised by Slater and conductor Tristram Williams riding with aplomb every tape stutter, enforced glide and mad looping. The Australian Art Orchestra and Slater, along with a very busy Vanessa Tomlinson on percussion, rise to this demanding occasion with precision and gusto.

Nicole Lizée makes impressive new music—and new audiovisual experiences—from the manipulation, decay and malfunctioning of old technologies. In this concert, the challenging melding of music and media reached a deeply satisfying apotheosis.

You will find music and video works by Nicole Lizée on her website.

–

Sydney Festival 2017: 1967: Music in the Key of Yes, Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House. 17 Jan; Ellen Fullman Long String Instrument, Sydney Town Hall, 13, 14 Jan; Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Seymour Centre, 9-15 Jan; Rautavaara, City Recital Centre, 11 Jan; Nicole Lizée, Sex, Lynch and Video Games, City Recital Centre, Sydney, 19 Jan

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017